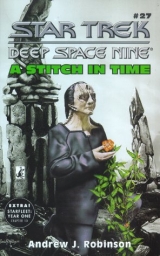

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Of course Remara is using me, I thought. For what, I had no idea. Traitor and thief. The mystery only sharpened my appetite.

12

Entry:

Tzenketh. Each assignment was farther away from Cardassia Prime, and of longer duration. Loval, Celtris III, Lamenda Prime, Kora II, Orias III. If I made a chart of my assignments from the beginning, each vector would penetrate progressively deeper into space. I wondered if this was a sign of advancement in the Order.

I had done what Tain asked, and in the following years no one was as dedicated a night person as I was. I went everywhere they asked me to go and stayed as long as it took to complete the mission, but Tain never said a word that would indicate whether he was pleased or displeased. In fact, I saw very little of him, and even less of Mila. This distance from them, and the fact that I was rarely home, actually made my work easier. My primary contact at the Order was Limor Prang, who became even less expressive, if that were possible, as he grew older. I knew, however, that my dedication, and the absence of any kind of life outside of the Order, concerned him. On those occasions he’d tersely suggest that I visit Morfan Province or some such popular vacation area. I’d tell him I’d consider it, and accept another assignment . . . or tend to my orchids . . . or walk.

The walking started when I knew I had to find a place to live where I could grow the orchids. Such a place is rare in the city, and when it appears the cost is prohibitive. I explored every sector, inquiring, following up possibilities, sometimes making a nuisance of myself. It was during this process that three things happened: I found a place, I learned to talk to all kinds of people, and I fell in love with the city and its various sectors.

The house was owned by a retired chief archon, Rokan Du’Lam, a man I later discovered was notorious for the sternness of his courts and sentences. He had a back apartment that opened out onto a modest plot of ground. I explained that I had limited means, but that I traveled a great deal and would gladly improve the fallow ground with plantings.

“What kind of plantings?” he hoarsely demanded. I was grateful that I’d never been dragged into his court.

“I am fond of Edosian orchids, sir.” He laughed in my face.

“Can’t grow those here!” he barked.

“I beg to differ with you, sir. I’m sure that under my care they would thrive.” He laughed again.

“I’ll tell you what, boy. If you can grow orchids here, I’ll let you have the apartment for the cost of the energy and resources. If you can’t, then you pay what I tell you.” It was clear that this was a man who did not suffer fools or braggarts.

I took a deep breath and agreed. I happily moved out of my basement, and every spare moment was spent preparing the soil for planting. On the day that I put in the sprouted tubers, the archon had invited a friend who lived nearby to witness the event. She was an older woman I had seen with him before, and she tended a small plot in the back of her home with simple, well‑integrated plantings. They both carefully watched me plant with pitiless expressions that expected failure. Neither of them said a word to me, but occasionally they would whisper to each other. At one point I heard the woman distinctly say, “I think he knows what he’s doing, Rokan.” After the last tuber was planted, they just looked at me and went into the house without a word. There was nothing to do now but wait; but I was certain that my new home was now well within my means.

During the waiting period, I often visited the Tarlak Grounds and Tolan’s orchids for inspiration. It was still one of my favorite places. I would sit in the same shaded spot where he’d told me about the first Hebitians, contemplating the elegant beauty of the orchids and listening to the children’s voices floating to me across the greensward. The magic of these flowers has fascinated me from the moment I first saw them. The mysterious way they reveal themselves, layer by layer. . . . Just when you think they can’t get any more beautiful, that you can’t learn anything more, another layer of bloom surpasses the previous one and the orchid changes personality. Recently I have developed a new indulgence–clothing–and I know it’s because of the influence of the Edosian orchid. Each time I put on another well‑designed and well‑tailored suit in a fabric with depth and an aesthetic pattern, I feel like another person. One of my favorite duties is to choose what I will wear for each assignment. As I smell the soft pungency emanating from somewhere deep in the soil, and observe the shaded pastels blend and reblend in a continuous flow, I realize that the Edosian orchid defies description and aspires to the condition of high art.

“Kel. Kel! Don’t wander off too far. We have to start home.”

The voice cut through me like an icy wind. I didn’t want to look. The same sweetness, piping and strong. If an Edosian orchid could speak. . . . I looked across the greensward, and there she was, the blue‑black hair and the long, dark gray skirt flowing behind her as she chased a little girl who was giggling, trying to escape from her mother but knowing that the beauty of the game was that she wouldn’t. Half of me wanted to run after them, the other half wanted to be buried deep in the ground. Why her? Why now? With sudden clarity I saw my entire life as a defense against this very moment. I didn’t want to feel what I was feeling; I didn’t want this immense burden of desire. I had learned to be satisfied with the occasional brusque sexual contact that quenched desire the way food or water did, and to live without any expectation of that touch that transforms routine into adventure. Watching Palandine and her daughter defy gravity with their dance of love destroyed all my definitions, and my carefully maintained boundaries began to give way, for the first time since Bamarren, to the magic of limitless possibility. I knew at that moment that I’d never be satisfied again. Even my beloved orchids looked like weeds.

I watched like someone unable to avert his eyes from impending horror, as the mother ran down the daughter and gathered her up in her strong arms. They were both giggling, absolutely fulfilled in each other’s company, lighting up the grounds with their radiance.

Palandine and Kel. And the other. Not present at this moment, but of course always there. Oh yes, I had kept track. How could I not? Especially when we have the resources to keep track of any Cardassian. Barkan Lokar was now an important administrator with the Bajoran Occupational Government. As much as my own work remained covertly placed in institutional shadows (and Tain made sure that I was publicly identified as a bureaucrat at the Hall of Records), Lokar’s was very much in the full light of the sun. Oh, I knew a great deal about him. Bajor, a planet rich in resources, was being skillfully stripped by his efficient programs. With the help of forced labor, the moribund Terok Nor outpost was being revitalized into a fabulously productive mining enterprise.

Lokar was the favorite of such powerful Cardassians as his father, Draban Lokar, and Procal Dukat, key members of the Civilian Assembly and Central Command respectively. In fact, his prefect on Terok Nor, the ore processing station, was Procal’s son, Skrain Dukat. Lokar’s ambition and his prospects had no limit. Nor, it seems, did his appetite for using and disposing of people . . . especially women. His tyrannical excesses, visited upon friend and foe alike, were well documented; but as long as his stewardship produced such successful results no one cared. Lokar has quickly become an integral part of the easy corruption I see and smell more and more at the highest levels of our system, and which gives the lie to our stern and moralistic faзade. Perhaps, I thought, when I leave for Tzenketh tomorrow I’ll erase all memory of the way back.

Palandine’s husband and Kel’s father.

I watched them leave the Grounds, but I stayed rooted to my spot waiting for a great hole to open up and swallow me. It didn’t. Darkness came, and the chill finally drove me to my feet. I started to walk.

Cardassia City is designed as a round wheel with the Tarlak Sector functioning as the administrative hub. This is where the public areas–the Grounds and the monuments, the government buildings–are located. Radiating out from the hub, like unequal slices of pie, are six sectors. I wandered first into the Paldar Sector, the residential area where Tain’s house was located, as well as the archon’s where I was lodging. It was one of the earliest settlements, and most families had lived there for generations. Government bureaucrats and civil servants who worked in the Tarlak Sector usually lived in Paldar. I walked past Tain’s house, stopping momentarily to wonder if other people felt so completely estranged from the home of their youth. There were few pedestrians, since this was the time of the evening when families gathered after a long day of work and school: The good Cardassians. The sector reeked of rectitude and self‑importance.

I decided not to return to the archon’s, and turned right at the Periphery, which marked the outermost limits of the city; beyond were the dry scrublands that contained shuttle terminals, military training areas, food‑producing centers, and isolated factories and settlements. I began to traverse the huge Akleen Sector (named after the putative founder of modern Cardassia, Tret Akleen), where the military was garrisoned. Troops were marching and drilling on parade grounds scattered throughout the sector, and civilian pedestrians were often challenged.

“Where are you going?” the sentry demanded.

“To the Torr Sector,” I replied.

“Why don’t you take the peripheral shuttle?”

“I want to walk.”

“You can’t walk here,” he stated. “You have to go around.” He pointed the way and I took it. I decided to return to the Periphery, to bypass the rest of Akleen and the adjoining Munda’ar Sector, which consisted of cavernous storehouses. I entered the Torr Sector, the largest and most populated and the place Cardassians come for food, entertainment, artistic displays, and public performances of music, dance, and spectacle. It was originally designed to house the service classes, and over the course of time it became the center of our cultural life. The streets were crowded with young men and women coming to and from the various restaurants and attractions. I thought I could lose myself in the crowds that filled the thoroughfares at all times of the day and night and enjoy the anonymity, but the jostling and the noise only made me more aware of the loathsome self‑pity I was feeling. I wanted my life to be arranged without need, to be totally self‑sufficient, able to do my work for the Order and find fulfillment wherever I could–to accept my life as enough. But how could I, when my deepest involvement was with orchids?

I moved away from the crowds, and into a quiet neighborhood of modest homes that reflected the Cardassian ideals of cleanliness and frugality. The walkways were narrow and immaculate; even the smallest homes were carefully maintained. Cooking smells filled the air, and I realized that I hadn’t eaten since morning. I also realized that I was not yet prepared to leave for Tzenketh in the morning. But what was there to prepare? Decide on my wardrobe, pack it, and close the door when I leave. The archon and his lady friend would be more than happy to tend the orchids. I’ll feel better, I decided, when I’m on the shuttle and immersing myself in the assignment. Then I can forget about her and do my work.

A group of people caught my attention. They were entering a larger building on the corner, and trying to maintain a low profile. I had witnessed this before . . . and in this sector, I realized . . . in this neighborhood. It was after the first cell meeting and the encounter with Ramaklan/Maladek. I shivered as I thought of him. Two people were behind me, and I was sure they were also part of this group. On an impulse I “withdrew” my presence, blended into the lower vibrating energy of this group, and entered through the rear of the building. Once inside, we walked down a flight of stairs to a darkly lit but surprisingly spacious basement that had twenty‑five chairs facing a slightly raised dais, empty except for a table. I took a seat at the back, and when I had settled I saw the sole decoration on the wall behind the dais: it was the winged creature from the stone carving. The face had the same features as the recitation mask Tolan had given me. I shivered again and wanted to leave immediately. I felt an irrational sense of danger, but the room had quickly filled up and I didn’t want to draw attention to myself. I also felt like a fool for following my initial impulse to come here. I looked around. The man next to me smiled. I tried to smile back, but my face was frozen. I couldn’t locate the source of my anxiety–there wasn’t the hint of a threat in the room–but my stomach was churning and my throat felt tight. I had to use all of my techniques to stem the rising fear.

The door closed from the outside and the lights changed to feature the dais. Two people rose from near the front and stepped up to the table. Without a word they each picked up a mask and held it a long moment, as if studying the mask’s neutral expression. They looked at each other, nodded, and fastened the masks to their faces. They took another long moment, now studying each other. Then they turned to us and moved to the edge of the dais, where they stood and made contact with every person in the room. I don’t know how long this went on, but a palpable feeling of expectation was growing in the room. Finally, the woman (or, rather, the person who had been the woman, as the masks had transformed them both into variations of the creature behind them) began to chant.

“The power that moves through me

Animates my life

Animates the mask of Oralius

To speak her words with my voice

To think her thoughts with my mind

To feel her love with my heart:

It is the song of morning

Opening up to life

Bringing the truth of her wisdom

To those who live in the shadow of the night.”

The man responded.

“It is this selfsame power

Turned against creation

Turned against my friend

That can destroy his body with my hand

Reduce his spirit with my hate

Separate his presence from my home:

To live without Oralius

Lighting our way to the source

Connecting us to the mystery

Is to live without the tendrils of love.”

There was another long moment of silence as the two people, their stature and the power of their presence somehow enhanced to the status of iconic figures, maintained their vibrant contact with each other and with us. Then they moved back to the table and reversed the opening ritual. As they took their seats, I wondered how two such ordinary people were able to expand their presence in such an extraordinary manner. The irony of my withdrawn presence did not escape me.

Someone began to hum a simple melody. After several repetitions, others joined in with haunting contrapuntal harmonies. The intensity of the sound gradually built in strength and insinuated itself throughout every part of my body. Every cell was being massaged by the sound, and without any conscious effort I began to hum harmony that was my own and that somehow fit in with the others. My body began to feel the benign warmth rising along my spine that only occurs with enough kanar.My anxiety had evaporated, and I felt connected to this group of strangers. The intensity kept building, and my whole being vibrated with such rhythmic insistence that I found myself swaying in a circular pattern. I was not the only one; the entire room was swaying. Occasionally a voice would shout out the name of someone and the others would forcefully repeat the name. When there were no more names the energy began to subside until we were silent again. I had never felt so in touch with every part of my body.

A woman simply but elegantly dressed in a white doublet, blouse, and culottes stepped up to the dais. Her bright eyes were set wide apart, and her look was somehow stern and at the same time kind. It was difficult to tell how old she was. When she spoke, her voice had an unstudied resonance, slowly and softly projected. She had the engaging talent of making you believe you were the person she was primarily addressing.

“I am your guide tonight,” she began. As she continued to speak the room was absolutely still. Her simplicity commanded, without any effort. She told us that the people had been healed, and to make sure that we had more names for the next healing. Looking directly at me, she welcomed the newcomers. I tried to deflect the look, but she was powerfully focused, and easily contained me.

“It takes courage to come here, to look at things the way they once were. And while they can never be that way again, we can extract an essence that will nurture and amplify our own lives. We can strive to be better friends and live with ourselves and others with respect and the recognition that each soul desires to be reconnected with the source. To enslave or prey upon each other is not how we began. We were connected to each other. We did not experience hunger, deprivation, or loneliness. We were connected, and we cared and nurtured and loved. No, friends, it’s not how we began. But if we end in isolation and hate, not even a monument in Tarlak will ease the agony of our lost soul.”

The meeting went on with more recitations, chanting, and readings from something called the Hebitian Records (“Where everything is written,” she claimed). There was a final meditation, and it was over. People rose, but instead of leaving they lingered and spoke to each other. I wanted to leave. The peace I had felt after the “healing” had been replaced by a deep disquietude that began when the “guide” directly addressed her remarks to me.

As I made my way through the crowd, I discouraged all contact others offered to make. I caught snatches of conversation, and by the time I reached the door I decided that it was all sentimental nonsense. Cardassia suffered a great climatic catastrophe–and if we hadn’t been strong and determined to adapt, we would have perished with the weak. And the weak mustperish; otherwise the integrity of the race is compromised and we become the preyed‑upon. Poor misguided Tolan. He was a good man but he was a gardener, and the worst thing he had ever had to do was kill weeds.

“Who sent you?” It was the Guide.

“A friend,” I replied vaguely.

“Ah,” she said with an odd recognition. “You’re a careful man. This is good. We’re not looked upon with favor by the authorities, you know.” She smiled at me, and I experienced an inexplicable surge of hatred. How dare she? How dare she set herself up as superior? This was a superstitious cult that undermined the fundamental tenets of Cardassian life. It deserved to be outlawed.

“I hope you’ll join us again.” She said this with a detached gravity, nodded and turned back to the others. I quickly went up the stairs and back outside, where I felt I could breathe again. As I began the long walk back to the Paldar Sector, I debated whether I should inform Internal Security about the existence of this meeting.

13

Ah Doctor, Dominion weapons have destroyed us, and as we resurrect ourselves the dead and the discredited are returning. After years of toiling in anonymity and exile, I have become a much sought‑after notable. This evening, as I was working on this chronicle, I had a visitor from the past–Gul Madred. I’m sure you know him by reputation; he had a distinguished service record marred only by the unfortunate incident with the Federation Captain Picard. He fell out of favor about the time I was stranded on Terok Nor. I almost worked with him in a proposed joint operation that involved both the Order and the military. It was a daring idea that made too much sense to succeed. The military would behave like a military, and take care of the fighting–and the Order would behave like an intelligence service, and get them the information they needed in order to behave like a military. Madred, however, was a key member of military intelligence and insisted that they did not want any involvement by the Order. He made it clear, however, that he did want certain techniques that we had perfected. We were reluctant, of course, to part with them and after several increasingly acrimonious meetings we decided to part with each other instead. I’m afraid we have never had much regard for their intelligence; the incident with Picard supports our low opinion. If nothing else, an interrogator must have the stamina to outlast his subject.

Still, I was delighted and utterly surprised to see Madred when he appeared at the door. I always regarded him as a cultured and serious man, and despite his troubles of recent years he was still very much involved with the future of Cardassia.

“I’m honored, Gul Madred. I’m also too woefully provisioned to offer anything more than a seat and some clean water.”

“You’re very kind, Garak.” Madred took the offered stool and I poured him a cup of precious water. “How did you find me?” I asked. The harsh lighting in my shed revealed a deeply lined face, with eyes that couldn’t hide an intense almost haunted weariness.

“Your necropolis has become the subject of much conversation throughout the sector,” he replied. “Or is it a memorial to your former mentor?”

“It’s whatever people want it to be. It seems to give comfort to some. For me it meant bringing some order out of this chaos.”

“Yes. And that’s what brings me here. We’ve had our differences in the past, Garak, and at times we’ve come down on the opposite sides.” It was rumored that his was one of the powerful families that had supported Dukat’s alliance with the Dominion. “But I’m hoping that we can find common ground during this transitional–and crucial–moment in our history. We must rise from this.” He gestured toward my “necropolis.”

“One billion dead. We have no choice,” I observed.

“But we must do it correctly!” He was passionate and emphatic. Something was driving him.

“You have no disagreement from me, Madred.”

“I know this. Because, like a true Cardassian, you arebringing order out of chaos–which is more than I can say about others in our sector.” He looked at me meaningfully, and I waited for him to continue.

“You’ve heard of the movement afoot to bring in Federation methods for determining our new leadership structure?”

“No, I haven’t,” I replied without hesitating. I prayed that Parmak wouldn’t make one of his unannounced nocturnal visits.

“Each sector will vote for a leader. Vote,Garak. Which means that a hygiene drone will have as much to say about our future as you or I.”

“Would this be true for everysector?” I asked. I hadn’t realized it had gone this far.

“Yes. And then the six sector leaders would form a council that would determine everything from rebuilding the infrastructure to rearming our military–and each of us would be subject to their decisions!”

“Sounds a bit too simple, doesn’t it?” I observed.

“Simple? It’s unbelievable. Who are these people? Alon Ghemor? A family of traitors. Korbath Mondrig, a rabble‑rouser from the service class. I wouldn’t have these people clean my shoes, let alone make decisions that determine our future!”

Madred had indeed changed since I last saw him; he was more neurasthenic, given to sudden emotional outbursts. I had to be very careful with him.

“What do you . . . suggest we do?” I asked softly.

“I’m in contact with a group of people–I can’t tell you their names yet–and we are in the process of mounting a serious counteroffensive to this . . . Federation model,” he nastily spat out.

“And what would you like from me, Madred?”

“Your support, of course. Unfortunately, it’s going to get rough, and we’ll need skillful operatives.” He graciously nodded to me. “We’re also going to need information. I understand you’re working with a Dr. Parmak who’s very much involved with Ghemor.”

“I was assigned to his med unit. The situation makes for strange bedfellows,” I added.

“Of course.” I found it interesting, Doctor, that for some reason it would never occur to Madred that I would actually enjoy my relationship with Parmak. I had the feeling that he was making an assumption about me that was perhaps reinforced by my involvement with the Order and Tain.

“Our work is winding down, however,” I shrugged. “We don’t see as much of each other.”

“Nevertheless, any information would be useful . . . and helpful to your cause,” he said with obvious meaning. It was at that moment, Doctor, that I knew I would never help these people. How many times while I was exiled on the station did I hear that expression “helpful to your cause”? I’d comply, time after time, but it never seemed that my cause–returning home–was ever advanced.

“And what do you think my cause is, Madred?” I asked with an ingratiating smile. He hesitated; the question wasn’t expected.

“I would think that given the past circumstances you’d want to find favor with . . .” He hesitated again. Who was left? Madred and his group?

“With Enabran Tain?” I suggested. He laughed, but he got my point. How typical of his class (and his military intelligence background) to operate from an outdated model.

“Let me see what I can do.” It was time to end the meeting. “It was a pleasure to see you again.” Madred rose and barely inclined his head. I was disliking him more and more. I escorted him to the door to get him out as quickly as possible.

“By the way, I bring you greetings from an old schoolmate of yours. Unfortunately I can’t tell you his name.”

“Ah. Please return my greetings.” Madred left, not a moment too soon.

Is it him? Is he still alive?

14

Entry:

While the design of a circle with a hub and six radiating sections is a simple one, Cardassia City is densely laid out with an angular and labyrinthine complexity that only the natives can navigate. As I became expert in my knowledge of every neighborhood and thoroughfare I developed an irresistible desire to secure new lodgings at regular intervals. I would pick an area and look for a place that would satisfy my need for privacy and my passion for Edosian orchids. While my hosts would be deeply disappointed at my departure, they were equally grateful for the gift of healthy orchids I would leave them. With the exception of the archon and his lady friend, however, I had little hope that these people would be able to maintain the orchids.

One of my genuine pleasures was to pick someone in the street to follow. Part of it was to satisfy a desire I’ve had since Bamarren to move through places and among people undetected, a desire that increased significantly after seeing Palandine and her daughter. In the intervening years, I’d pick someone who looked like a walker and follow him or her as long as they walked. I’d make sure my presence was minimized and I’d take on the person’s physical carriage and behavior. After a while, once the physical mimicry felt complete, I’d also take on the thoughts and feelings of that person. In this way I not only felt connected to another, but I was divested of my own thoughts and emotions–especially the painful ones.

Because I could never stop thinking about her. It was a terrible possession, and the more I told myself to stop or tried to employ gimmicks to distract me, the worse it got. I often returned to the Tarlak Grounds in hopes of seeing her; most of the time I sat among Tolan’s orchids in vain. And the few times she did appear . . . ah, how can I describe the feeling? A poet once described, “an exquisite pain/ Churning the heart, the stomach, and the genitals.” Crude, yes, but anatomically correct. It is so curious how we can learn to live with just about any condition or situation if we believe we have no choice.

Palandine and Kel appeared on this day, and I realized that Kel was getting too old for the children’s area. I could see that it was Palandine more than Kel who wanted to come to the Grounds. Palandine would stretch into the sunshine and try to encourage her daughter to run and wrestle with her. Kel, however, had developed a taste for novels and rebuffed all her mother’s efforts to play. The spaces between their visits to the Grounds were widening, and sooner than later they would stop coming altogether. By my calculations it wouldn’t be much longer before Kel was sent to an Institute. As I watched them, I became consumed with these inevitable changes and wasn’t sure what I would do.

As they left the Grounds, my body had no problem deciding on a course of action: it followed them. I knew this was dangerous, and my anxiety made me unsure how to proceed. I knew where they lived in the Coranum Sector, the oldest and most prestigious neighborhood in the City. But what was I going to do? Stand outside their home and live off the occasional glimpse? This was folly. But there was no turning back . . . my body kept following. We passed through the crowded great public area, where Palandine ran into two women she knew. They were standing in the shadow of the Assembly building, and I had to be watchful for colleagues. Finally they moved on, and for a split second I considered retiring to my cubicle in the Hall of Records and distracting myself with a huge amount of deferred work, but my body followed. I couldn’t let them go.

We entered the Coranum Sector, and the contrast was dramatic. Stately old buildings dating back to the early Union faced wide thoroughfares; they weren’t cramped and pushed together as in the Torr. The care and craftsmanship lavished on the facades made even the fine homes of the Paldar Sector look boring and drab. These were the homes of the families who had ruled Cardassia for generations, and they were built to reflect the solidity and continued longevity of that rule. Of course the Lokars would live here.