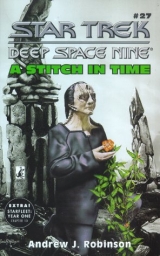

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

The investigators caught up with her, and she turned away from me as Odo led them through the airlock. I realized that I had stopped breathing.

I left my pudding, stopped at Quark’s to buy a bottle of kanar,and retired to my quarters. It took half of the bottle before I began to breathe again; and only when it was empty did I finally ask myself the question: Why hadn’t she betrayed me as I had betrayed her?

4

A deep sadness I had not felt in a long time reemerged as I walked through the Coranum Sector to my meeting with Madred and the group he referred to as the Directorate. Not one of the old, stately buildings had been spared by Dominion revenge. Perhaps there was a cruel justice at work here, Doctor, since these were the families that had initially agreed to the alliance with the Dominion. But if anything marked the end of Cardassia as we remember it and symbolized the stripped and naked state of our civilization, it was the devastation of this first settlement, the “birthplace” of the Union.

The sadness was most keenly felt when I passed the Coranum Grounds. Every bit of vegetation had been engulfed by the firestorm, and any evidence of that soft and protected place of assignation had been reduced to ashes. I quickened my pace.

As I stood in front of the building debris I tried to locate the entrance to the basement Madred had described. Judging from the enormous amount of rubble that had already been cleared, this had been an impressive home. Finally, I made out a path that led to the rear of what would have been the ground floor, and followed it to a temporary structure that functioned as both an entrance and a cover for the staircase. The darkness swallowed me as I carefully made my way down the stairs and into a makeshift anteroom. At that moment a door opened and Madred appeared.

“Ah, good. I was concerned that you weren’t coming,” he said with some irritation. I realized that I had gotten lost in my thoughts as I’d walked through the sector. In a sense, Doctor, my new world has become timeless, especially in the absence of all my old routines and landmarks.

“I wanted to make sure no one was following me,” I lied. At our previous meeting, when I’d suggested that I might be able to provide some helpful intelligence about the Reunion Project, Madred warned me to maintain absolute secrecy about the meeting and its whereabouts.

“Did you notice anyone?” he asked with concern.

“No,” I replied. Actually I could have been followed by an army and I wouldn’t have noticed. I’m afraid I’ve become careless as well as timeless, Doctor. Madred led me down a short corridor that had formerly been much longer but truncated now to adjust to the new living circumstances.

“Is this your home?” I asked as I followed him.

“What’s left of it,” he replied. A door opened, and we entered a large room badly lit by several emergency lamps. The city had to live with intermittent blackouts as the power grid was being realigned. As my eyes adjusted, I was able to discern the shapes of seven people arranged around a table in the center of the room. Most of them looked familiar, and I wasn’t surprised to see them here. One person, however, did surprise me. Two people I didn’t know. My “schoolmate” wasn’t here.

“This is Elim Garak. Some of you may know him,” Madred said as introduction. He offered me a seat and took his place to my right.

“Elim Garak,” the person to my left repeated with amused wonder. “How are your tailoring skills these days?” he asked. It was Gul Hadar, who had been one of Dukat’s aides on Terok Nor; a man of weak character who easily participated in the worst excesses of the occupation.

“Under the present circumstances, Hadar, they come in quite handy,” I replied. He nodded, studying me in his diffident manner. He also came from one of the old families.

“I wonder if that’s why Madred invited you here.” He turned to the others. “Because Skrain Dukat claimed Garak was a dangerous traitor who was responsible for the deaths of his father and Barkan Lokar. Are we in need of a tailor?”

“Skrain Dukat was the traitor,” said the voice across from me. It was Gul Evek, a blunt, unsmiling soldier who I’d thought had been killed pursuing the Maquis in the Badlands. “I think we can safely say that anyone who was his enemy has a right to be here. Especially anyone who fought with Damar.” He looked at me with his stern face, and I acknowledged his support. I heard Hadar sigh, and understood that the “Directorate” was far from unified.

“The issue is not Dukat. It’s the future of the Union!” the man next to Evek maintained. This was Legate Parn. He challenged the group with a look that made me believe that he was the leader in this room. Parn had administered the Cardassian colonies in the demilitarized zone after the treaty with the Federation, a treaty he and Evek had believed was the beginning of the end when Cardassia signed it. They were outspoken in their view that accommodation with the Federation had fatally compromised our resolve.

“The dead are dead. Those of us left–who believe in the ideals that have guided our race for millennia–are faced with the threat of utter annihilation by the very disease that has brought us to this sad place. Federation ideas will finish the work the Dominion began.” Again he challenged each of us. I followed his look. On the other side of Madred was Nal Dejar, a sharp‑faced, saturnine woman who had been a member of my last cell at the Order. She once came to Deep Space 9 on an as signment with two scientists, and refused to make any contact with me. Judging from her averted look, she was still refusing. Next to her was a man with a severely disfigured face that was still recovering from what appeared to be burns. One eye was completely covered, and I was careful not to be rude in my inspection. He and an attractive woman sitting on the other side of Evek were the two people who weren’t familiar to me.

The surprise guest, Korbath Mondrig, sat between this woman and Hadar. Considering that Madred believed he was nothing more than a demagogue stirring up the service class with old resentments and divisive rhetoric, I wondered how this group planned to use Mondrig.

“Let us be clear about what unites us,” Parn warned. “We have our differences. We’ve even had our troubles in the past,” he said, looking directly at me. “But they can’t be allowed to deter us from our main purpose.”

“Which is?” I asked, returning his look.

“To crush any attempt by any group to espouse Federation ideals as we rebuild our society,” he answered.

“Rebuild it to where it was before we doomed ourselves with that treaty,” Evek added.

“And I believe that’s why you’ve joined us today, Garak,” Parn said, never taking his eyes off me.

“If I may,” the woman next to Evek spoke up. I was grateful for her interruption; I needed more time to orient myself. She signaled to Madred for recognition; he appeared to be the moderator.

“Of course, Gul Ocett,” he replied. So this was Malyn Ocett, I realized; the only resistance leader who had survived when the cells were betrayed by Gul Revok. Her courage and resourceful tactics had not only inspired her followers, but her call to the military after the Lakarian City massacre was largely responsible for our soldiers turning against the Dominion at the crucial moment.

“I share Legate Parn’s concern that the Federation wants to ‘absorb us,’ ” she said. “All of us here know their strategy has never been a military one; it’s political. At this point, we’re weakened, vulnerable. The Federation recognizes that the current dislocation is the moment to inject us with their democratic ideas, because there are people like Natima Lang and Alon Ghemor who would gladly carry them to the rest of us.” Natima Lang, Quark’s old paramour, was obviously back on Cardassia along with every other political opportunist. “We’re deeply wounded now, and if we’re not careful we could end up with a political system that would not only place us firmly within Federation hegemony, but would destroy our identity.”

Gul Ocett was persuasive in her quiet and reasoned strength. Indeed, the irony, Doctor, is that she was espousing the very argument I had made to you any number of times. Even now there was a part of me that accepted the logic of her argument, especially when coming from someone who was neither a fool nor an opportunist. Gul Madred saw his opening.

“I think this is the moment to let Korbath Mondrig speak and explain what we have in mind as a strategy.” Madred nodded to Mondrig, a physically small man who had been listening very carefully.

“Thank you,” Mondrig said with a smile his closely set eyes didn’t share. “Unless, of course, others wish to express their views,” he graciously offered. The only people who hadn’t spoken were Nal Dejar and the disfigured man. Because of her training and naturally closed face, Dejar was hard to read. Not a flicker of recognition registered when she saw me. And the man’s face was so damaged and his body so still, he had almost no presence. Both of them remained silent.

Mondrig nodded. “It is an honor to be among people I consider heroes of the Empire,” he said.

“What little is left of it,” Evek muttered. Hadar sighed again, and Evek gave him a hard look but held his tongue.

“Yes, unfortunately, as Gul Ocett has said, we have been deeply wounded.” Mondrig’s tone was deferential, almost obsequious, but there was a mannered quality I didn’t trust. At that moment he looked right at me. “And I must confess that the presence of this gentleman surprises me as well. Forgive me,” he nodded in my direction, “but in our Paldar Sector he is associated with Ghemor and Parmak. If I’m not mistaken, you even held a rally for their Unity Project at your . . . memorial?” It was phrased as a question, but the intent was clear. The attention of the others now shifted to me.

“Reunion Project,” I corrected.

“Yes, of course,” he accepted the correction.

“How chummy,” Hadar commented.

“Yes, I hosted the rally,” I admitted.

“Why?” Hadar asked.

“I admire Dr. Parmak. I’d been working with him on a med unit, and when he asked if he could use my home for a rally, I agreed.”

“Why?” Hadar repeated with the satisfied look of a clever interrogator.

“Because I wanted to hear his point of view,” I replied.

“You’ve lived on a Federation outpost for how many years?” Hadar asked pointedly.

“I also went to school with Alon Ghemor, and I’ve always found him to be an honorable man.”

“A family of traitors!” Hadar concluded, looking at the others as if he’d made some damaging point about my character. I simply smiled at him, genuinely amused by his amateur attempts to discredit me. I was surprised by my responses. I was here to play the role of double agent, and I found that as the meeting went on I didn’t have the energy for the requisite guile and misdirection.

“What are you telling us, Garak?” Parn challenged. I smiled at him. It was so transparent, what they were doing. So predictable. Each sector was planning to choose a leader. A council would then be formed from the “elected” leaders of each sector, which would lead the city and most likely a reorganized union. Public sentiment for this democratic process was too strong to oppose, especially when there was no longer an army to throw against the heretics. The Directorate wouldn’t oppose the vote, but they would get around it by backing their candidate in each election, thus creating a council that would then become an instrument of their will.

“What are you telling us?” Parn repeated the challenge.

And then a strange sensation went through me, Doctor. I looked at the faces of these people. Here we are, I thought, sitting in the basement of a ruined civilization and conducting business as if nothing significant had changed. The enemies were still the same, somewhere “out there,” plotting how to “destroy our character” and colonize us with their political system. And we were down in the basement with our own plots and shifting alliances, tenaciously holding on to the very ideas that had brought us here. But what ideas, Doctor? There’s nothing left. Only fantasies of power. These faces with their masks. With the ironic exception of the disfigured face, the masks hadn’t changed. They reflected the usual range of hidden agendas, each competing for dominance and ascendancy with an energy commensurate to the amount of fear and self‑loathing that fueled and motivated that person. I started to laugh.

“Does my question amuse you, Garak?” Parn asked, his mask revealing the anger and the lust for power that fueled hisagenda. He didn’t even try to disguise his impatience with me. The ideology, the patchwork of old ideas and mythology was in place; the boundaries that determined what was sacred and received “truth” and what was heresy were set: all that remained was for him to arrange the power structure and assign each person his or her role in it. He was the deal maker, the broker–and he wanted to get on with the business of satisfying his lust.

I looked around the table, from face to face, mask to mask. Evek and Ocett were honorable soldiers who had dedicated themselves to the old ideals of Cardassian purity and superiority. But the failure of the system that had contained these ideals, and the ensuing devastation, had left them deeply troubled and confused. What was their responsibility in the breakdown? Who was this man Parn hastily reassembling these ideals into a system they both knew could never be the same? But their education, their conditioning, their having been bred to a society that answered all problems with a received set of answers enabled them to question only so far. Parn had skillfully used limits set long ago; beyond them was the demonized void dominated by Federation ideas waiting for the right moment to attack.

Unlike Evek and Ocett, Mondrig was a little man without a center, Parn’s propagandist and puppet, whose job was to stand in front of the people with a mask that would mirror our beliefs, our prejudices, our hopes, and our fears. He was the consummate politician who would deliver the message in a way that would never threaten or challenge us. He desperately aspired to belong to this group, the repository of Cardassian power, and the group only wanted to use him for the demagoguery that would further entrench its power.

Hadar was a degenerate. His mask, like the features of his face, was without the definition of a life that was lived and thought and felt. He accepted his privilege without question or gratitude to those forebears who had passionately struggled for their beliefs. He believed in nothing but his appetites. The ultimate parasite.

Madred had the same forebears, but his mask was sharper than Hadar’s because he still had the passion of his beliefs: he desired to maintain the old ways at all costs because anything else was inconceivable. He would even associate himself with Mondrig, a man he’d said he wouldn’t let “clean his shoes,” if it meant the old order could be restored. There was fear in his mask: the fear of change.

Nal Dejar’s mask was closer to home; she reflected my own religious dedication to the “secrets of the state.” We lived in the shadows, and our masks played with light and darkness, like the regnar’s skin. We passed through life like Tain’s “night people,” with no allegiances except to the secrets. And the more successful we were, the slighter and more invisible we became, until we easily occupied space the way a shadow falls across light.

And the disfigured mask, the most honest one in the room. . . . The one good eye, peering out at me from an interior prison of pain and bitter disillusionment, gave me permission to study his mask–and we made contact.

It washim, Doctor. It was Pythas.

“My friend,” I whispered. I think only Madred and Nal Dejar heard me.

“Are you willing to help us?” Parn asked harshly, his attention still focused on my loyalty to his cause. I remembered my conversation with Tolan about the price of “status.” “Or are you sympathetic with these people?”

“Yes,” I replied, taking my eyes away from Pythas. “I am indeed.” I rose from my chair. “I shouldn’t be here. This is not my place. I apologize for the intrusion.” I looked again at Pythas. I didn’t know what to say to him. But even with his one good eye he could still communicate with depth and meaning. Not here, he told me. Not now. Madred also rose.

“Thank you, Gul Madred, but I can find my way out.” I bowed to the company, and turned my back on them.

5

Entry:

Ever since the negotiations came to a conclusion, and with the transfer of Terok Nor to the Federation now imminent, I’d waited for some kind of communication concerning my status. Nothing but silence. Still, I was certain that my exile would end with the Occupation, and that soon we would all be on our way back to Cardassia Prime. This morning I decided to go about my routine even though I had no real work to speak of. After all, if the garrison and all Cardassian civilians are scheduled to depart today, why would any of them leave garments with me? However, I still had my own clothing designs to wrestle with.

When I came out onto the Promenade, I was stunned. It was like a holiday. The Bajoran population had obviously been celebrating all night. Groups of them were singing, dancing, holding each other up as they staggered and howled their delight. Debris was everywhere, as they tore down and scattered the remnants of the makeshift shelters they had lived in for so many years. I could hear the din from Quark’s bar, which evidently was doing a booming business. I ducked back into the shop as several inebriated celebrants came careening my way. When they had passed, I stepped out to where I could see more clearly down the Promenade. There wasn’t a Cardassian in sight. The only officials were Bajoran military and Federation people. The withdrawal had taken place during the night, and Terok Nor was now Deep Space 9.

I heard someone yell, “The tailor’s still here.” I hurried into my shop and locked the doors behind me. I stood in the darkness, trembling. Not a word. Nothing! They’d left me here. I wanted to contact someone. To protest. But ever since I had filed my last report about the negotiations, they had cut me off. I felt impotent. Ashamed. Elim Garak, a Cardassian tailor on a Federation outpost, cowering from drunken Bajorans.

There had to be a limit. My crime was a serious miscalculation, no doubt; I had ignored the warning, disobeyed my superior, and given in to the passion of my life. But I had dedicated myself to the state! This couldn’t possibly be unpardonable . . . not when idiots and butchers are promoted and prosper every–

The door chime rang. I froze. I wondered about my status. Would I be allowed to remain in the shop and work? Did I want to? Did I have a choice? The chime rang again.

“Yes?” My attempt to sound normal was pathetic.

“Are my c‑clothes ready?” It was Rom. I had forgotten that I was still working on the suit of clothes he had “bought” from his brother.

“Just a moment.” I turned on the lights and took a moment to compose myself before I let him in.

Rom was apologetic. “I thought you were open, otherwise . . . .”

“Not to worry, of course I am,” I brusquely assured him, as I fetched his tunic and trousers. “And I think you’ll find everything fits quite well.” I held the curtain to the changing room open for him, and he took the clothes and entered. I pulled the curtain closed and checked behind the counter to see if there was anything left in the kanarbottle. There wasn’t even a bottle.

“How, uh, did you know I’d still be here, Rom?” A quaver undermined the attempted nonchalance.

“My brother said you would be, but I wasn’t sure, and when I saw that the Cardassians had left during the night . . . .”

I could tell from his tone that he wondered why I hadn’t left but was too shy to ask. Strange people, these Ferengi. Rom had a sensitivity, almost a delicacy that was totally lacking in his brother. Was there such a thing as a typical Ferengi? Most people judged him to be simple, as if simplicity was somehow a substandard quality. He came out of the changing room wearing his new garments. I had certainly dressed him like a Ferengi, and I could see that he was pleased.

“Tell me, Rom. Are they all gone? The Cardassians?” I stopped trying to disguise my concern. Rom looked at me with that fearful directness of his and nodded.

“Y‑yes. Late last night. Gul Dukat passed the station over to the Federation and a Commander . . . Sisko and . . . they left.” He still wanted to ask why I had stayed.

“Well, Rom, the trousers and tunic fit quite well, don’t you think?” I pulled the tunic down at the back. “Don’t wear it so far up on the neck; it ruins the line. And I’d be grateful if you’d tell any interested parties that indeed I’m still here and very much open for business.”

“Oh, yes . . . yes! And I like. . . .” Rom made a broad, awkward gesture toward his new ensemble. I thanked him, and we walked out onto the Promenade, as if it were just another business day. We said good‑bye, and I watched him march proudly through the ragged celebrants. I had a fondness for him. It was an odd relief, especially at this moment, to converse with someone who literally meant everything he said. My attention was drawn to a group of drunken Bajorans across the way who had interrupted their celebration to stare at me with hostile disbelief. They had the same question as Rom. I smiled graciously and went back into the shop.

I sat in the shop and tried to busy myself with a design that had been eluding me. It was almost as if the suit was designing me, and I thought that somehow this was appropriate at this stage of my life. I had my back to the door, but I could hear a crowd gathering outside. Their sounds were low but threatening, and I knew that my presence was the focal point. Would rule of law prevail now that the Occupation was at an end and I was the only Cardassian left on the station?

Individual voices could be heard yelling from the crowd and urging that action be taken. I could sense the growing anger as their numbers increased. And they weren’t complaining about their pants. The muscles of my neck and shoulders were tense as I sat hunched over the work table. I erased another design and started again, chasing the design that in turn was chasing me.

Someone broke away from the crowd and stormed into the shop. I braced myself, but I didn’t turn to face her: a woman screaming at me in a peculiar Bajoran dialect that was totally incomprehensible. I continued to work, focused on a design that was now oddly coming to life. I could feel the heat of her rage, and believed that there was no way to confront it without making the situation worse. But more people had entered the shop, and suddenly I was grabbed from behind with great force and pulled to my feet. I stumbled against the table, quickly regained my balance, and turned to confront a Bajoran man who immediately realized that he needed the rest of the crowd to follow through with his intent. The others stood behind him and the moment was suspended. No one spoke, no one moved. We just looked at each other. Their hatred was a unified field that blurred all individual distinction. I realized in that moment the gravitational field of the station had been adjusted to a heavier setting, and the wave of hatred flowing from these people made it even more oppressive. I felt as if I were carrying twice my weight. I fully expected to be torn to pieces.

“That’s enough!” a harsh voice commanded. The constable of the station, the shapeshifter Odo, was standing at the top of the outside steps. With his customary dignity he made his way through the crowd, which was now half in and half out of the shop.

“Clear this space,” he told them. “Go on! Get about your business.” Two of his Bajoran officers were directing people back onto the Promenade. Odo grabbed my attacker unceremoniously by his shabby tunic and turned him over to one of the officers.

“Put him in the holding cell,” he instructed. As the man was escorted off, several parting curses and threats were hurled from the Promenade. “Are you harmed?” Odo asked me in his formal manner.

“No, not at all. Thank you for your concern . . . and your intervention,” I replied. He stood for a moment, studying me, trying to divine why I had not been allowed to join the withdrawal. Unlike the others who assumed that because I was a Cardassian I had a choice, Odo knew that I’d been abandoned.

“Was there any damage or theft?” he asked.

“No,” I answered. I knew little about Constable Odo, but I was confident that he would never ask me questions that went beyond his function as security chief. He kept his distance and carried himself like someone who understood exile.

“I will make sure that nothing like this happens again.” Odo gave one last look around the shop, wondering, I’m certain, who was going to do business with a Cardassian tailor. He left with the same lack of ceremony with which he’d entered.

The room was suddenly empty. I studied my reflection in the full‑length mirror. Changes were in order for my new life. For one thing, I thought, I’m too heavy for this gravitational field. I patted my stomach: silence, exile, cunning . . . and less spice pudding.

6

The Directorate wasted no time: a “Restoration Cadre” was established in each sector. Ostensibly its purpose was to maintain order while Cardassia recovered enough “strength of will” to restore its former governing structures. The Directorate presented itself as the legitimate agent of this restoration, and in each sector the Cadre supported the Directorate’s choice of leader. In the Paldar Sector they had chosen Korbath Mondrig.

The reality, Doctor, is that the Cadre functions to intimidate the people of each sector into accepting this restoration and condemn the Reunion Project as a subtle Federation corruption. But instead of submitting to the Cadre’s threat of violence, many people throughout the city–and indeed the planet–are resisting and organizing along the lines of the Project. For these people, a restoration means returning to the conditions that created the rubble and dust that now surround and choke us.

For the first time in our modern history, Doctor, we are faced with a choice between two distinct political and social philosophies. The crucial question is howwe are going to make this choice. Is a consensus achieved by peaceful means? Or do we now go to war with each other?

I had anticipated the current stalemate. I had even anticipated what happened last night, when I was awakened from my usual fitful sleep by the sounds of falling debris. For a moment I thought we were still under Dominion attack. I jumped up and looked outside. Several men dressed in the makeshift Cadre uniform and led by someone I recognized as one of Mondrig’s aides were pushing over the roughhewn memorials. I set off a loud alarm I had created for just this kind of event. After the rally for Alon Ghemor, the grounds had become a magnet for the Reunion. In an amazingly short period of time scores of my neighbors, including Parmak and Ghemor, had appeared. The outnumbered marauders, expecting a violent confrontation, prepared for battle. We had agreed beforehand, however, that violent resistance was pointless; all that would happen would be a further escalation of violence until one side dominated the other and we would be left with less than the nothing we now had.

It was an eerie scene, Doctor: mute witnesses, men and women, surrounding a phalanx of sweating belligerents prepared to fight to the death. Cardassian against Cardassian–a unique and disturbing sight. Some of the marauders were ex‑soldiers following new masters, some were no more than orphaned children. Some probably were in the service of the restoration ideal of returning Cardassia to its former imperial glory. Most were just hungry and desperate. It was a dangerous tactic on our part, Doctor, and as the tense and silent standoff continued I could see certain faces on both sides giving in to the strain. It was only a matter of moments before something happened.

Suddenly one of the younger marauders broke ranks and attacked a man across from him. Several of the witnesses immediately reacted to defend the fallen man.

“Hold!” Ghemor commanded. They did. No one retaliated and the young marauder stood over the man with a confused look. He had hoped, I’m sure, that his action would have been absorbed by an ensuing battle; but now, being the focus of every eye, he had no choice but to accept sole responsibility for his act. When he received neither guidance nor approval from his superior, he found the attention unbearable and ran off. The standoff continued, but now the marauders became restless. The watchful stillness of the witnesses began to unnerve them. If they weren’t going to fight . . . ?

“This is shit,” an older soldier muttered in disgust. He looked around at his companions and at Mondrig’s aide in contempt. “Shit!” he repeated with greater force. His hard face and warrior poise told me that he held no fear of battle. “Shall I fight women?” he asked the aide. To answer his own question he spat and walked off into the night. His uneven gait and low center of gravity reminded me of Calyx.

Mondrig’s aide attempted to salvage the situation, and ordered the marauders to continue the destruction of the memorials, but the older men took the lead of the grizzled veteran and dispersed. The younger inexperienced men realized that they were no match against the organization of the witnesses. And it was this discipline that also reminded me of Calyx. Ghemor had not only learned how to “hold his place” in the Bamarren Pit, he was able to teach others as well.

After the remainder of the Restoration Cadre had made their careful retreat, the witnesses, without any perceivable instruction to do so, began to rebuild the toppled piles. When someone voiced the worry that he wasn’t sure how the formation had looked before the damage, I assured him that it didn’t matter. Dawn was breaking when we completed our repair work, and people began returning to their homes. Parmak, Ghemor, and I stood silently among the formations, inspecting the results of our work in the first light.