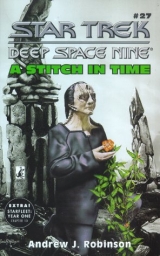

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Look at the Vulcan,” he directed me to a tall man with sad eyes. “They haven’t the spine of a sandworm, but at least they’re intelligent. They can grasp the complexities of a given political situation. I just hope Oonal is equal to the challenge,” he said as he changed his focus to our “father,” who was speaking with a short, graying Human.

“You mean Krai,” I corrected. We were strictly instructed to use our story names.

Maladek looked at me with the expression he usually reserved for humans. “I think I’ll try to have an intelligent conversation tonight.” He moved off in the direction of the Vulcan, who was now standing alone. He does remember me, I thought, and he knows the role I played in the Competition. I decided at that moment that I had to watch him as much as the enemy.

“Hello.” I’d been so focused on Maladek that I hadn’t heard anyone approach. Standing next to me was a young human whose hair was as white as mine was black. I just stared at him. I’d never been this close to one of them.

“My name is Hans Jordt,” he said carefully, not sure if I was on another communication level.

“My name is Alardig Ra’orn,” I finally was able to reply. His insignia indicated that he held the rank of lieutenant, junior grade. He was solidly built, for a human, and his eyes were a shade of pale blue I’d never seen before.

“Forgive my ignorance,” Hans began, “but what sports do Cardassians play?”

“Sports?” The question was so odd that I thought we might indeed be on different levels.

“Games. Contests.” Hans attempted to be helpful, but it only got worse. I suspected this was obviously a clumsy attempt to cover a deeper intent.

“Perhaps I should explain,” he bravely continued, in the face of my utter incomprehension. “A few of us are attempting to organize a game of football. Have you heard of it? Some people call it soccer.”

“I’ve heard of it, but I’m afraid I wouldn’t be of much help. Cardassians don’t play.”

“Ah–then perhaps you’d like to learn. We could play among ourselves, I suppose,” he indicated the other humans in the room. “But I thought it might be interesting to get the other groups involved.”

Hans looked at me with such intense, blue‑eyed openness that it was difficult to maintain any kind of distance. He was a junior member of the Federation delegation, and certainly an intelligence probe. But that wasn’t the problem–I welcomed this contact–it was the football. We don’t play sports, at least not the team sports that Federation people have been trying to popularize throughout the quadrant. I could accept boxing and wrestling, which were primitive forms of pit competition, but basketball was mindless monotony and games like cricket and baseball were completely incomprehensible.

“I’d be pleased to participate,” I replied, “but how could I possibly contribute? I know nothing about the game.” As much as I wanted to establish contact with these people, I certainly didn’t want to make a fool of myself.

“Yes, of course,” Hans nodded in agreement. “But there is one position that does not require skill so much as athletic ability.” He then gave me a lengthy and rather boring description of the game: defenders, midfielders, strikers working together to push a ball they were not allowed to touch with their hands or arms into an opponent’s goal. Hans suggested that I participate as a goalkeeper.

“You see, all you would have to do is prevent your opponent from putting the ball into your goal.”

“And I can’t use my hands?” I asked.

“No, the goalkeeper can use any part of his body,” Hans replied with the widest grin I have ever seen on a face. Children and their games, I thought. I had no idea of what I was getting into, but I agreed to defend one of the goals. It was at least a concept I understood.

After the reception, as I was laying out what I was going to wear for the next day’s football match, I could hear Maladek in his residence. He was talking as he moved about. His voice was too soft for me to tell if he was talking to himself, into a recording device, or to someone else. I realized that I had lost track of him after I’d made contact with Hans, and I didn’t see him for the rest of the evening. At one point, he laughed–a loud bark, really–and what sounded like a bottle crashed against the wall. There was a long silence punctuated intermittently by a sound I could only describe as a painful moan. A strange person, I thought as I fell into a disturbed sleep.

“Cut off his angle, Alardig!” I heard Hans instruct me as the “striker” broke through the defense with skillful control of the ball. I was all that was left between him and the goal. It was happening with the speed of a dream. The striker–a short, wraithlike Starfleet officer they called Mahmoud–feinted to my left, and my inexperience followed him. Just as my weight committed, he easily cut back to my right and kicked the ball into the back of the goal net. Ah yes, I thought, I understand now. That won’t happen again.

And it didn’t. For the remainder of the match I calculated distance, angle, and speed in such a way that Mahmoud’s goal was their last. Hans was quite impressed with what he called my “uncanny anticipation,” and suggested that I should pursue the game and introduce it to Cardassians. I smiled and imagined what would happen to this game if we adopted it. If they give “yellow cards” as warnings for slight infractions, and expel a player for the hard bump, kick, or trip, then a group of Cardassians would be gone in a matter of minutes. Even in today’s game, there were complaints about the vigor of my defense, and I was trying to be “sporting” (to use the Federation expression). In our “games” you win by eliminating your opponents–or at the least severely limiting their ability to compete.

Still, it was quite instructive, especially during the time (which was most of the match) when the action was away from me and I was able just to observe. There is undoubtedly a skill to the game, and most people play to win (indeed, humans are capable of being every bit as aggressive as Cardassians), but they exhibited such a childlike joy and enthusiasm as they played that I came to understand another meaning of the word “game.” What was more puzzling, however, was watching those people who played the game for no other reason than to . . . just play. If they or one of their teammates made a mistake, if the opposition scored . . . they didn’t seem to mind. Some even laughed it off. And at the end, every one actually shook hands and congratulated each other.They’re not stupid–Maladek has dangerously underestimated them. But there’s something we don’t understand about these humans that limits our effectiveness in dealing with them.

There was quite a crowd for the match, which was due more to the fact that, other than hiking or turbogliding or attending Embassy functions, there wasn’t much to do on Tohvun III. At the beginning I noticed Maladek watching with the tall Vulcan. Hans told me that he had tried to get Maladek as the other goalkeeper. I wasn’t surprised that he’d refused; it was clear to me that he found his time better spent with the Vulcan, who was also a nonplayer. When we came back from the interval, the two of them had disappeared.

“Thank you, Alardig,” Hans said to me at the reception for the players. “I can’t get over how well you controlled your goal.”

“Perhaps Cardassians have the ideal temperament for the position,” I half joked. “Too bad you didn’t get Begom for the other goal.”

“Then we might not have won,” Hans laughed. “But tell me, is he not feeling well?”

“Begom?” I asked.

“Yes. I only ask because he seemed perturbed when I approached him about the match.”

“He’s always perturbed,” I said without thinking. At that moment I understood two things: I didn’t like Maladek, and I had made a huge mistake. Hans was looking at me with his open face, so seemingly free of guile or ulterior intent. I immediately covered my misstep with a laugh and desperately tried to think of something that would mitigate my remark. But the laugh was artificial and the longer Hans stood there–smiling at me!–the more I felt the fool. Of course. Far from being stupid, these people know exactly what they’re doing. Hans also knew what he was doing when he asked me to goalkeep. It was clear that they had more information about me than I had about them.

And Maladek knew all this as well.

The thought struck me as I made my way to the service compound, where I was to meet Limor. He was posing as an Embassy employee, although I hadn’t seen him since I’d arrived. I sent him a message that I wanted a meeting as soon as possible, and he directed me to the groundskeeping building. I didn’t know what else to do. As a junior probe I had limits, but what were they? How much do I respond to Hans’s obvious interest in me? And what do I do about my increasing uneasiness concerning Maladek? A shadow moved, and Limor was next to me.

“Come with me,” he said. Where had he come from? I followed as he quickly led me behind the building, through a back door, and into a small room I took to be the groundskeeper’s office.

“What is it?” We stood in the darkness.

“It’s Maladek. It’s also the Starfleet junior officer, Hans Jordt. It’s also . . . me.” I struggled to organize my thoughts. I knew somehow there was a coherence, but I didn’t have enough information to put it together for myself. Limor watched me, waiting patiently. I decided to start at the beginning. I told him about Bamarren and the Competition and how I was “certain that Maladek remembers not only who I am, but the part I played in his defeat.” I told him about Maladek’s contact with the Vulcan, his behavior with me and the sounds that were coming from his room. And I told him about Hans, the football match, and my unthinking reply to his interest in Maladek’s well being.

“I know something is going on, Limor. But I’m missing something. Perhaps if I had more information. . . .”

“You’re here to observe and to learn,” Limor reminded me. “Information comes if your assignment expands. Otherwise, continue.” He nodded dismissal and I started to leave.

“You can hear Maladek. He can’t hear you.” I stood at the door, letting this sink in. “And breathe once before you answer any questions.”

As I walked back to the residence I understood that my assignment had expanded. I also understood that this expansion had been anticipated when I’d been given my residence. Very little is left to chance in this work. Even the lack of preparation for dealing with humans, which had so irritated me (and had made me think that Limor had been remiss) served a valuable purpose. Hans Jordt would not have shown such interest, I’m sure, if I had behaved in a “prepared” manner. The skill, I realized, was to assimilate these lessons without losing my innocence.

When I entered the residence, I immediately placed a chair next to the wall that connected to Maladek’s. He was in there, restlessly moving about and muttering. I could only try to imagine the state of mind that impelled anyone to behave with such agitation. Not satisfied with my listening post, I tested various parts of the wall for better hearing. Not only did I find a slight indentation that allowed me to hear perfectly, but it also contained a cleverly disguised eyepiece that gave me a wide‑angle view of Maladek’s room. Why hadn’t they told me about this to begin with? Because, my voice patiently explained, any expansion also depends upon information I uncover myself. Another piece of the mosaic.

Maladek was moving about the room as if he were being chased by fire. His muttering came in scattered bursts, and there were times when I was convinced other people were in the room with him. I could only make out the occasional word, and only then if it was repeated, like “yadik,” which is what a young child calls his or her father. There was much about betrayal and someone called the “betrayer.” As he harangued the room, he helped himself liberally from a bottle of crinox,a strong drink fermented from local berries. It was a pathetic sight, and one I never would have guessed from the self‑contained superiority of his public face.

I watched him until he drank himself into a stupor and fell asleep in his clothes. The closest thing I could liken his behavior to was a man defending himself desperately before a chief archon who had judged him guilty. But even more disturbing was the impression that this presumption of guilt was driving him mad.

That night, my dreams reflected just how disturbed I was. Somehow I was barely hanging on to a steep ledge high up on a huge rock formation that dominated the Mekar Wilderness. In front of me was the flat summit and safety, behind me was a sheer drop into the jagged outcropping of the formation and certain death. A figure was on the summit offering me a rope to hold onto. The sun was behind the figure and I couldn’t make out who it was. I kept repeating, “Who are you?” But the person wouldn’t answer. I refused to take the rope until he did answer, but the surface was slippery and it was getting increasingly difficult to keep my footing. Finally, I had no choice and grabbed a rope. The person maintained the tension on the rope as I carefully climbed up. I stopped to take a breath and calm my anxiety.

“It’s an opportunity, Elim,” the voice said.

I looked up, and it was Barkan.

“It’s an opportunity,” he repeated and threw his end of the rope over the edge behind me.

I sat up on my pallet, bathed in sweat. I instinctively knew it was late, and that I had to hurry to get dressed and meet Hans at the main entrance. I had agreed to go on a hike with him up the Mandara volcano. I hoped that my dream had no connection to the day’s activity. As I was leaving the residence, I looked toward the eyepiece in the wall; something in me didn’t want to know what was happening on the other side. But it was my work, and I couldn’t pretend otherwise. It was also in my interest to know, especially if the dream (as I suspected) was connected in some way to Maladek. I looked–but the room was empty.

“I’ve been told that this way has the greatest views,” Hans said as he set a vigorous pace up the trail. It was clear that he was an experienced climber, and I followed, taking special care negotiating the broken lava rock and twisting roots. The density of the planet’s atmosphere and the chilling dampness made the climb more taxing than I had expected. Finally we came to a clearing that afforded a view of the Mandara Valley rising up to a volcanic range of mountains, which floated above a bluish mist. Thankfully, there was direct sunshine that warmed the rocks we sat upon and helped to dispel the forest chill.

“This reminds me of my part of Earth,” Hans said as we gazed out over the valley. He explained that everyone in his family loved to climb and hike. “If we manage to come to an agreement, many people from Earth would come here to vacation. I assume Cardassians would also visit Tohvum and Dorvan if there were peace between our peoples, no?”

“We tend to stay within the limits of our Union.”

“Except where resources are involved,” Hans said cheerfully, watching carefully for my reaction.

“What would you have us do? Cardassia is not a rich place like Earth. We have to live.” I was equally cheerful in my reply.

“Everyone has the right to live, Alardig. But does it have to be at the expense of others?”

“If that’s the competition, so be it. Very often, Hans, the game is about survival.”

“But surely there’s another way of dealing with scarcity than forcibly occupying another homeland and reducing its people to the level of vassals and slaves.” Hans continued to smile, and I wondered if he really believed these sentiments–or was this another example of Federation hypocrisy? These people reduced all political complexity to pious platitudes, while they constructed the greatest empire in the history of the Alpha Quadrant.

“Have I been brought to this beautiful place to be subjected to a critique of our Bajoran policy?”

Hans laughed and looked out to the distant mountains. As the sun moved behind some clouds a cold wind kicked up. When he turned back he was no longer smiling.

“Your brother is not well. I’m sure you know that.”

I took a long breath and nodded. “He hasn’t been well for a while.” I wasn’t sure where this was going, but it felt right.

“Then you’re concerned about his welfare.”

“We all are.” The art is to thread and extend meaning, using as few words as possible.

“Is he getting the help he needs?” So concerned, so caring. I took another long breath.

“Well . . . it’s difficult. In our culture. . . .” I shrugged.

“Is that why he came to us?”

“Yes,” I answered immediately, instinctively feeling that any hesitation would alert him to my ignorance and subsequent scramble for footing. I looked Hans in the eyes and resisted being swallowed by their immeasurable blue depths. I shivered against the cold. Hans saw this; I couldn’t pretend that it hadn’t happened.

“He’s not a traitor. But he needs help. I told him not to go to you, that we’d find a way. . . .” I trailed off, translating my ignorant isolation into that of someone caught between two powerful forces. Tears came to my eyes, and I marveled that I had absolutely no emotional attachment to them.

“We know he’s not a traitor. When Saurik came to us and explained the situation, he made it clear that your brother had no other recourse.” Yes, the Vulcan. Careful now. Another breath.

“That’s true,” I replied.

“What usually happens to people in your culture who suffer from a . . . mental imbalance?” Hans was now treading delicately; clearly, they needed my help with Maladek. I wondered if he had really gone to them, or if they had enticed him in some way. Or was this all a lie?

“We kill them.” Something very sharp emerged from the blue depth of Hans’s eyes, and for the first time I was afraid I had gone too far. But it was too late to back down; I had to rely on human prejudice.

“Cowardice and madness are unforgivable,” I went on. “They reflect flaws in the Cardassian character that can never be redeemed.” This was to a certain extent indeed true of cowardice; madness, however, was looked upon as a mysterious disease, and those who suffered were isolated and treated well. In any event, no one was killed unless the cowardice occurred in battle.

“My God,” Hans breathed, confirming, I’m sure, his belief that we were capable of any kind of atrocity. I hated his self‑righteous superiority, and calculated the several moves that would send him flying into the abyss. Instead I turned and sat down on a rock that still held warmth from the departed sun. I put my head in my hands to give him the impression of my utter vulnerability.

“So, Alardig. What do we do now?”

“Father had hoped that if he brought Begom on this trip–got him away from home and the pressures–but it’s only gotten worse. Father can’t even concentrate on his work. We never should have come here. I’m afraid. . . .” I stopped as if I’d gone too far.

“Of what?” he asked. I just shook my head.

“I understand,” Hans said, thinking that he had me. There was a long silence. “We’ll take care of Begom. You have my word. I think I know a way.” I looked at him, full of gratitude.

“Thank you, Hans.”

“But we will need your participation. I am going to set up a meeting as soon as possible.”

“With Begom?” I asked, hiding my concern.

“No. With the people who are helping him.”

“Anything I can do . . .” I assured him with heartfelt sincerity.

“I know. Well . . .” Hans looked around, smiling again.

“. . . we’d better get back before we lose the light.”

As we came down the trail, I wondered about Maladek and his illness, the people who were “helping” him, and the exact nature of my participation.

That night I reported to Limor, and he checked and double‑checked every detail I had related with probing, specific questions. I assumed that it was because the situation had reached a critical point and he was concerned that a probe was in the middle. But the discomfiting thought did occur to me, as I patiently responded to his interrogation, that he was also scrutinizing my veracity. I was about to ask him if he doubted what I was reporting, when he preempted me.

“I may put you on the enhancer.”

I said nothing. It was enough of a challenge just to return his look.

“How would you feel about that?” he asked.

“I would . . . submit, of course.”

“Is there something you’re not telling me, Elim?”

“No.” I continued to hold his look and knew better than to ask him anything now; I would only appear defensive. I waited in the long silence, and refused to back down.

“Consult your comm chip. There is some information I want you to pass on to Hans Jordt when you see him next.” I was dismissed.

Hans contacted me two days later, and we took another hike up the Mandara. Once again he set a grueling pace on a different, steeper trail. As I struggled to keep up, it occurred to me that breaking me down physically was certainly a part of his strategy. When we stopped to “admire the view” (Hans’s sentimental expression), I didn’t try to hide my exhaustion. I flopped down, panting heavily, and giving the not untrue impression that I couldn’t go any further.

“Are you all right, Alardig?” Hans asked, barely showing any effects at all of the arduous hike. I nodded. He watched me as I “struggled” with my breathing. He took a small instrument from his pocket and waved it over me. I was warned by Limor to deactivate my comm chip, because Hans would check to see if I was recording the conversation. He was satisfied that I wasn’t.

“We’ve found someone who can help Begom.”

I nodded again, pretending that it was still too difficult for me to speak.

“But to give him the help he needs, we’re going to need some information.”

I waited for Hans to continue.

“He speaks of betrayal, and he mentions you.”

“Me?” I didn’t have to feign surprise.

“Yes. Why would he say that about his own brother?” Hans asked.

“I don’t know.” And I didn’t know how to reply to this. “What else did he say about me?”

“He told us not to believe anything you tell us. According to him you’re here to pass on misinformation regarding the Cardassian position, and you represent an intelligence agency that wants to scuttle these talks. He says that you’re not even his brother.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. What did Maladek think he could accomplish by telling them this? Was this his revenge for what happened at Bamarren? Or was this another example of having only the information I needed for the moment? I had no choice but to stay with my story. I didn’t even try to hide my true confusion from Hans.

“Are you a spy?” he asked.

“No. And I really don’t know what there is to spy about. The negotiating positions seem to be common knowledge. Troop withdrawals from the neutral zone. Unarmed observers on all planets in question to monitor the truce and withdrawal. Cardassian control of Dorvan V. These are the main points. What’s left are the details.” This was an accurate summation.

Hans thought for a moment. “You’re well informed.”

“I’m here to work with my father and learn. And I thought Begom was as well. Unless . . .”

“Unless what?” Hans asked.

“Unless he’s playing a dangerous game. No one pretends that a settlement with the Federation has the unanimous support of the Central Command. There are elements in the military who’d like to see these talks fail. I’m just afraid that Begom may have gotten involved with them.”

“So now you’re accusing each other.” Hans was skeptical.

“But why would he say such a thing about me?” I asked fervently. “He hasn’t been well ever since he came back from Bamarren.”

“And Bamarren is . . . ?”

“It’s our state security school. He suffered a terrible humiliation there, and I know he wants to do something that will somehow erase the shame. I’m afraid he’s involved in something that’s way over his head. He’s playing some kind of game with you, Hans, and I think he’s trying to impress someone.”

“Who?” Hans asked.

“Father,” I said, as if finally understanding. “Father always expected that Begom would be the one who’d go to the diplomatic institute and follow in his steps. When Begom went to Bamarren, Father was hurt and turned to me. Ever since, he’s been trying to prove to Father that he made the right choice, but after the fiasco at Bamarren. . . .” I nodded vigorously, kicking up dust as I paced our small clearing.

“I don’t know what he’s telling you, Hans, but if it’s anything like what he’s said about me, then be careful. He’s angry and he’s disturbed, and he’s going to say whatever he feels he needs to to redeem his pride and honor. He’s always been an adventurer, and this whole spy business–I’m certain–is just another game to him.”

Hans didn’t say anything. He looked out over his beloved rain forests receding to the distant string of volcanoes, and his face was a mask.

“What was the information you wanted from me?” I asked after a long silence. Hans grimaced as if to dispel an unpleasant thought.

“No, Alardig, I think you’ve told me what’s necessary,” he said with formal politeness.

“I hope it’s of use in helping Begom.”

“I think this is a family matter, don’t you? Begom and his father need to sort things out.”

“Ah, if only they could, Hans,” I said with a sigh.

We traced our way back down the volcano. I never saw Hans Jordt again.

I reported to Limor that evening. As I gave him every word, gesture, and detail he never took his eyes off of mine. After I had finished, I sat in silence while he made some notes on a comm chip that seemed to come out of his hand. The silence deepened as he waited for what I guessed to be a reply to his notes. There were so many questions I wanted to ask, but by now I knew that I was only going to get the information I needed to proceed–and nothing more. I had no idea as to what Maladek was up to, and I was worried about my improvisation that afternoon with Hans. Limor looked up from the comm chip.

“You will return to Cardassia tomorrow morning. Stay in your quarters until someone comes for you, and be ready to leave immediately.” Limor’s tone was flatter than usual, and I was worried even more that somehow I had botched my assignment–whatever that assignment had been. I nodded and moved to the door.

“You did well,” he said in the same flat tone. It was amazing how quickly and completely my spirits changed. “But tonight you are to leave your comm chip on, so I can hear everything in your room. Do you understand?” I wasn’t sure if I did.

“Yes, of course,” I assured him.

Limor just looked at me. “Stay on your toes, Elim. This assignment is not over.”

The first thing I did when I returned to my room was to check the eyepiece, but Maladek wasn’t in his room. I wondered if he would ever return. Had he gone over to the Federation? Had they murdered him? My imagination was attempting to fill in the missing pieces. What was this about? I packed my things to be ready in the morning, and sat in a chair fully clothed with my phaser concealed but accessible. I adjusted the comm chip so that Limor could monitor. What I was waiting for I wasn’t quite sure, but I had an idea.

* * *

There were all kinds of eyes staring at me. Strange blue ones that studied me like a specimen. Soft brown ones that signaled regret. Hard red eyes that looked at me with unaccountable hatred. I opened my eyes, and the red eyes were still staring at me. They belonged to Maladek, bloodshot with an inner torment I had only witnessed through the eyepiece. I realized that I had fallen asleep. How long had he been in the room?

“Maladek–what?” I started to get up, but he pushed me back. I didn’t resist, because I saw that he had a small phaser in his hand, and I was better off in the chair anyway because that’s where my phaser was.

“When I saw you at the cell meeting I knew you were nothing but trouble. Just as before.” His deadly tone sent my hand for the phaser, but I couldn’t find it.

“Maladek, I have never meant you any ill. . . .”

“From the beginning. With Charaban. You were an instrumental part of my betrayal.”

“What betrayal?” I asked. “It was the Competition, and it was my duty to fight you and try to win.”

“But you weren’t supposed to win!” he shouted, raising the hand with the phaser. I still couldn’t find mine. It must have slipped deeper into the cushions.

“Of course we were. Winning is the obligation of any Cardassian.” I didn’t know what he was talking about. He laughed with that loud, unpleasant bark.

“You’re good, aren’t you? They sent me back. They said I wasn’t stable enough to trust. They said I should work it out with my Father!” He laughed again. “If they only knew. What did you tell them?”

“Tell who?” I asked.

“Don’t play with me again!” He raised the phaser and moved toward me. I wondered if Limor was hearing this. “Twice is enough, Ten Lubak!” Another bark. “A Ten!” he said with spitting disgust. “You threw that body at us and I knew Charaban wasn’t keeping his end of the bargain.”

“What bargain?” I suddenly didn’t care about the phaser.

“You don’t know, do you?”

“No.”

“It was supposed to end in a stalemate. Neither of us would win. That way, Charaban could still assume leadership, and my placement after culmination would have been higher than an Obsidian probe.” He suddenly looked at me as if he was seeing another person.

“Why did you leave Bamarren?” he demanded.

“I was told to,” I replied.

“Why?” He couldn’t compute this. “You were one of the unit leaders. You should have advanced with the betrayer.”

I said nothing. I was not about to explain my own betrayal. Maladek began to weep.

“What did you say to them? You said something about my father.” Somehow I knew he wasn’t talking about “Oonal.”

“I told them that you were in over your head and that it was because you were trying to prove something to your father.” His eyes were suddenly furious, and he grabbed my neck with his free hand and held the phaser up to my head.

“What do you know? What do you know about anything?” he screamed in my face.