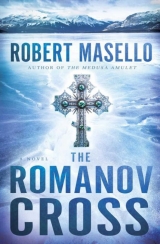

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Chapter 14

Perched atop the hard seat of the Zamboni, Nika Tincook wrestled with the sticky gears. The machine was probably thirty years old by now, so a little trouble was only to be expected. Besides, the city budget of Port Orlov did not allow for any new expenditures. No one knew that better than she did.

Wrapped in the beaver-skin coat her grandmother had made for her, topped off with a Seattle Seahawks stocking cap, Nika shoved the gearshift again, and this time it caught. Under the lights of the hockey rink, she steered the old Zamboni in wide, slow sweeps, cleaning and resurfacing the ice. She always found the job relaxing, almost like skating with her hands folded behind her back. No one else was out there – everybody was home making dinner – and she could be completely alone with her thoughts.

Which was all the more reason why she was annoyed at the increasing noise she began to hear. At first, she thought something had gone wrong with the Zamboni again, and she actually bent forward in her seat to hear the motor better, but then she realized the commotion was coming from somewhere farther off. And it was coming fast.

Looking up at the sky, she saw lights approaching – red and white ones – but not spread apart the way they would be on a bush plane. They were concentrated, and two bright beams were searching the ground as the craft got closer. It was a chopper – a long and weirdly articulated one – and as it clattered into view above the town’s community center, she realized with horror that the beams were now moving in her direction and fixing on the rink. She was bathed in a blinding white glow, and a bullhorn started issuing orders from on high.

“Please move the Zamboni off the ice,” the voice announced.

“What the—” But she was already turning the wheel and gunning the engine up to its full ten miles per hour. The racket from the chopper was deafening, and bits of snow and ice skittered every which way across the rink.

As soon as she’d driven down the ramp and into the municipal garage, where the city kept everything from its snowplows to its ambulance, she switched off the engine and raced back outside.

The helicopter, its wheels extended like an insect’s legs, was lowering itself onto the ice that she had just finished polishing. What could this possibly be about? Please God, not another news crew dispatched to recap the Neptunedisaster and interview the sole survivor, Harley Vane. Like a lot of people, she didn’t even believe Harley’s account, but the truth, unfortunately, lay somewhere at the bottom of the Bering Sea.

The rotors were turned off, and as they wheezed into silence, the hatchway opened, and a burly man with glasses stepped out. He slipped on the ice and landed with a smack on his rump. Laughing, he was helped up by another man, lean and tall, who guided him toward the steel bleachers. Nika crunched across the hard-packed snow and hollered, “Who are you?”

The two men noticed her for the first time. The tall one had dark eyes, dark hair, and reminded her of long-distance runners she had known – and dated – in college. He moved across the slippery ice with a becoming assurance and agility, but he didn’t reply.

“And who told you,” she went on, “that you could land on our hockey rink?”

Pulling off a glove, he extended his hand. “Frank Slater,” he said, “and sorry about the rink. But we were low on fuel when we saw your lights.”

“Lucky there wasn’t a game on.”

“And I am Vassily Kozak,” the professor said, bowing his head, “of the Trofimuk United Institute of Geology, Geophysics and Mineralogy. It is a part of the Russian Academy of Sciences.”

Now Nika was more puzzled than ever.

“We’re here on some important business,” Slater said, and though she ought to be used to it by now, her back went up at the slight hint of condescension in his voice. Because she was a woman, and young, and, to be fair, had been caught driving the Zamboni, he was just assuming she was some underling.

“I need to talk to the mayor of Port Orlov,” he said, showing her a bulky sealed envelope addressed to the city hall. “Could you show me where to find him?”

“Is the mayor expecting you?” she said, as sweetly as she could muster.

“I’m afraid not.”

“You came all this way, in the biggest chopper I’ve ever seen, without making an appointment?”

“There wasn’t time.”

“Right,” she said, skeptically. “Email is so slow these days.”

The professor was looking around with interest, and he said to them both, “Would you forgive me if I went for a short walk? I would like to stretch my legs.”

“No problem,” Nika said. “It’s hard to get lost in Port Orlov. The street’s that way,” she said, pointing off to one side of the big clumsy buildings, raised on cinder blocks, that comprised the community center. To Slater, she said, “You can follow me.”

They picked their way across the hard, uneven ground and entered the center. Geordie, her nephew, was sitting at a computer console, plowing his way through a bag of potato chips.

“Why don’t you bring us some coffee?” she said. “And knock off the chips.”

She led Slater down the hall, past the community bulletin board covered with ads for craft workshops and used ski gear, and into an office with battered metal furniture and a ceiling made of white acoustical tiles, several of which were sagging.

“Have a seat, Mr. Slater,” she said, shrugging off her coat and hat.

“Actually, it’s Dr. Slater,” he said, in an offhand tone that carried a welcome touch of humility. “I’m here from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, in Washington.”

If she hadn’t guessed already, now she knew that this was a serious matter.

Geordie waddled in with the cups of coffee and a couple of nondairy creamers.

“You can just leave those there,” she said, clearing a space on the desk by shoving stacks of papers around. Slater took off his own coat and put the envelope down on a free corner.

“I should warn you,” he said, “another chopper will be arriving tomorrow morning, so if there’s anyplace in particular you’d like it to land, just let me know.”

At least he was being accommodating, she thought, despite all the mystery. But two helicopters?

“So what’s all this about?” she said.

“It’s best, I think, if any information was disseminated from your own mayor’s office.”

“In that case,” she said, picking up the envelope, and using a whalebone letter opener, “let’s see what we’ve got.”

He started to protest, even raising one hand to take the envelope back, but the smile on her lips must have given her away.

“Don’t tell me,” he said. “You’re N. J. Tincook – the mayor?”

She pulled out the folder inside. “Nikaluk Jane Tincook, but most folks just call me Nika. Nice to meet you,” she said, though her eyes were fixed on the official warnings, and top secret clearance stamps, on the cover of the report. The title alone was enough to knock her out of her chair. “AFIP Project Plan, St. Peter’s Island, Alaska (17th District): Geological Survey, Exhumation, Core Sampling, and Viral Analysis Procedures.” And the report attached, she saw from a quick riffle through the pages, must have been sixty or seventy pages long, all of it in dense, single-spaced prose, with elaborate footnotes, indices, charts, and diagrams. The last time she’d had to wade through something like this was in grad school at Berkeley. “You expect me to read this now?” she said. “And make sense of it?”

“No, I don’t,” he said.

“Then why didn’t you send it on in advance?”

“Because, as you’ve seen from the cover clearances, we’re trying to stay under the radar as much as possible.”

“Why?” She was starting to feel exasperated again, and it looked like Dr. Slater could see it. He sipped his coffee, and then, in a very calm and deliberate tone, said, “Let me explain.” She had the sense that he had done this kind of thing many times before, that he was used to talking to people who had been, for reasons he was not at liberty to explain, kept in the dark.

As he laid out the case before her, her suspicions were confirmed. The stuff about the coffin lid and Harley Vane she already knew, just as she knew most of what he told her about the old Russian colony. She had grown up in Port Orlov; everyone there knew that a sect of crazy Russians had once inhabited the island and that they’d been wiped out in 1918 by the Spanish flu. She even knew that the sect had been followers of the mad monk Rasputin, who was said to have bewitched the royal family of Russia, the Romanovs, in the years before the Revolution. But out of politeness, and curiosity about where all this was going, she let him run on. As the grandma who raised her had always said, God gave us only one mouth, but two ears. So listen.

Truth be told, she also liked the sound of his voice, now that he was talking to her like an equal.

“Rasputin’s patron saint was St. Peter,” Slater explained.

And see, she thought, that was something she hadn’t known.

“The coffin lid bore an impression of the saint, holding the keys to Heaven and Hell. That’s one way we knew where it came from.”

“But apart from Harley Vane’s washing up there, nobody’s set foot on that island for years. It’s got a very bad reputation among the locals. How do you know for sure?”

“We did a flyover an hour ago. We could see where the graveyard had given way. The permafrost has thawed, and the cliff is eroding.”

Nika’s phone rang, and she hollered, “Pick it up, Geordie! No calls.”

“That’s why we have to set up an inspection site there, exhume the bodies, take samples, and make sure that there is no viable virus present.”

And it suddenly dawned on her, with full clarity, why this had all been kept so secret. My God, they were talking about doing something that was, first of all, a serious desecration of old graves – the sort of thing her own Inuit people would take a very dim view of – but even worse, they were talking about the potential release of a plague that had wiped out untold millions. That was one lesson that no native Alaskan escaped.

“But why here? Those bodies have been buried for almost a hundred years. Why would you think that they would contain a live virus when there are graveyards all over the globe filled with people who died from the flu?”

“But the bodies there weren’t flash frozen and kept in that state ever since.”

In her mind’s eye, she pictured the woolly-mammoth carcass that had been unearthed, nearly perfectly preserved, when they built the oil and gas refinery just outside town. She was just six years old then, but she remembered staring at it, feeling so sad, and wondering if it had been killed by a dinosaur.

“What about the risk to this town? If there’s a threat a few miles offshore, that’s a lot too close for comfort in my book. Are we going to have to evacuate? And if so, for how long? Who’s going to pay for that, and where are we supposed to go?”

She had a dozen other questions, too, but he held up his hand and said, “Hold on, hold on. It’s all in that report.”

“Thanks very much,” she said, acidly, “but as we’ve already discussed, it’ll take me all night to read that thing.”

“The risk,” Dr. Slater said, “has been calculated to be well within reasonable limits, and just to be on the safe side, we will be proceeding under Biohazard 3 conditions at all times. Any specimens will be taken on and off the island by Coast Guard helicopter. They won’t even pass through Port Orlov. We will only need this town as a temporary staging area. We’ll have assembled, and be gone, by the day after tomorrow. Nobody needs to go anywhere.”

For the moment, she was pacified, but she still wasn’t happy. She had come back to this town in the middle of nowhere because she felt a responsibility to it, and to her native people. She knew the history of their suffering, and she knew the toll those terrible misdeeds continued to take, down to the present day. There wasn’t an Inuit family that didn’t still feel the pain from the loss of their way of life, not a family that wasn’t fractured by depression or alcoholism or drugs. She had made it out, with a scholarship first to the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, and then the graduate program in anthropology at Berkeley. But she had come back, to be their voice and their defender. Only right now, she wasn’t sure how best to go about it.

The phone rang again, cut short by Geordie picking up down the hall.

“I know I’ve given you a lot to digest,” Slater said, but before she could answer, Geordie hollered, “When you said no calls, did you mean the sanitation plant, too?”

“Yes!” she called back, exasperated.

“But I’d be happy to answer any other questions you have. I know you’ll have plenty more.”

A gust of cold air blew down the corridor, followed by the sound of stamping feet. Professor Kozak leaned in the doorway, his glasses fogged and his face ruddy. “Is anyone hungry? I am hungry enough to eat the bear!”

It was just the note of comic relief that Nika needed. She smiled, and Dr. Slater smiled, too. His face took on a wry, but appealing, expression. She found herself wondering where else he had been before winding up in this remote corner of Alaska. From the weariness that she also saw in his face, she guessed it had been a lot of the world’s hot spots. “I’m not sure they’re serving bear,” she said, slipping the report into her desk drawer, then locking it, “but I know a place that does the best mooseburger north of Nome.”

Chapter 15

Charlie had been in the middle of a webcast, sending out the word from the Vane’s Holy Writ headquarters – and of course soliciting funds so that the church could continue its “community outreach programs in the most removed and spiritually deprived regions of America’s great northwest”—when his whole damn house started to shake.

His wife Rebekah had come running into the room with her hands over her head and her half-wit sister Bathsheba right behind her shouting, “It’s the Rapture! Prepare yourself for the Lord!”

Charlie almost might have believed it himself, except that the sound from on high reminded him so much of a helicopter. Out the window, he could see spotlights whisking back and forth across the backyard and the garage, where he kept his specially equipped and modified minivan.

Whipping around from the Skype camera on his computer, he’d wheeled his chair out of the meeting room and onto the back deck, just in time to see this huge friggin’ chopper moving like a giant dragonfly over his land. It was no more than fifty feet off the ground and looked to him like it was on some kind of close-surveillance mission. For a moment, he wondered if the federal government was sending a black-ops team to take him out; he’d certainly been known to say some inflammatory things about those bastards in Washington. The lighted cross on top of his roof, it suddenly occurred to him, might as well have been a bull’s-eye.

But the chopper moved on, skimming the treetops, then disappearing over the ridge and heading in the general direction of the community center. He listened as its roar gradually decreased, then grabbed his cell phone out of the pocket of his cardigan and called Harley. First he got the automated message, but he called back immediately, and this time Harley, sounding groggy, picked up.

“How the hell did you sleep through that?” Charlie demanded.

“Sleep through what?”

“That helicopter that just about knocked my chimney off.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about the military chopper that’s scoping out the town. I bet it’s got something to do with you and that coffin.”

“Charlie, next time you decide to flip out, call somebody else.”

“Don’t you dare hang up,” he warned. “Now get up and get your ass down to the Yardarm and find out what’s going on.” The Yardarm Bar and Grill was the local equivalent of a switchboard.

“Why don’t you go?”

“ ’Cause I’m in the middle of my broadcast.”

Harley laughed. “To who? You really think anybody’s listening out there?”

Charlie did sometimes wonder how many there were, but envelopes containing small checks and five-dollar bills did occasionally show up in his mailbox, so there had to be some. Not to mention the fact that he had two women in his house who had found him over the Web.

“I’m not gonna argue about this,” Charlie said, with the authority that always carried the day. “Get going.”

When he hung up and turned around on the cold deck, Rebekah was standing in the doorway with her hands in the pockets of one of her long dresses. Bathsheba was lurking right behind her, apparently persuaded that the Rapture had been postponed. Their white faces and beaked noses put him in mind of seagulls.

“We lost the connection online,” Rebekah said. “I told you we don’t have enough bandwidth.”

* * *

Harley dropped the phone on the mattress and lay there for a while. Why did Charlie always get to call the shots? It couldn’t be because he was in a wheelchair; it had been like this his whole life. Angie had told Harley he should just leave Port Orlov and start over someplace where his brother couldn’t boss him around. And he was starting to think that, dumb as she was, she was right about that much. If this graveyard gig worked out, and the coffins did contain valuable stuff, then that just might be his ticket to the good life in the Lower 48.

He wouldn’t even give his brother his phone number.

Getting up, he stumbled around the trailer, looking for some clean clothes – or clothes that would pass for clean – and ran his fingers through his hair in lieu of a proper brush. The floor was ankle deep in detritus – beer cans, cereal boxes, martial-arts magazines – and all of it was bathed in a faint violet glow from the snake cage on the counter next to the microwave. Glancing in, he saw Fergie curled on the rock, and he said, “You hungry?” He couldn’t remember when he had last fed her, so he opened the freezer and took out a frozen mouse – it was curled up like a question mark in a plastic baggie – and nuked it for about a minute. Once he had left one in too long and the stench had made the trailer unlivable for a week. He’d had to move back home with Charlie and the witches, and that was so creepy he couldn’t wait to get out of there. Bathsheba, in particular, kept turning up outside his door on one dumb pretext or another.

The trailer was parked about a hundred yards off Front Street, between the lumberyard and a place called the Arctic Circle Gun Shoppe. Harley had never asked anybody if he could park it there, and nobody had ever told him he couldn’t. That was one thing that you couldsay for Alaska – the place was still wide open.

But freezing. Even though the Yardarm was only a few minutes’ walk away, by the time he got there his ears were burning from the cold, and he had to stand in the doorway soaking up the heat. The usual crowd was around, Angie was carrying out a tray of burgers and fries, but some things were different: there were two guys at the bar he had never seen before – real straight-arrow types, still in their Coast Guard uniforms – and over in the far corner, Nika Tincook was at a table with two other men he’d never laid eyes on. Four strangers in one night, in a bar in Port Orlov – that was positively breaking news.

On her way back to the kitchen, Harley snagged Angie by the arm and said, “What’s up?”

“Harley, don’t do that here – the boss is watching.”

But he couldn’t fail to notice that her eyes had flitted in the direction of the two Coast Guard dudes, one of whom had glanced back.

“Who are they?”

“Pilots.”

“I can see that.”

“Were you just handling those dead mice again?” she said, wrinkling her nose. She brushed at the place on her arm where he’d been holding her.

“What are they doing here?”

“You got me. Why don’t you ask them?”

She pulled away and went back through the swinging doors into the kitchen.

Harley, hoping nobody had noticed how she shrugged him off all of a sudden, sauntered over toward the bar and eased himself onto a stool near the Coast Guardsmen. Engrossed in their own conversation, they didn’t acknowledge him in any way.

He ordered a beer and then, leaning toward them, said, “Never seen you guys around town.”

“Just passing through,” the one with the blond crew cut said, but without turning around.

“On that chopper that flew in?”

The red-haired one – who’d been checking out Angie – nodded warily.

“Oh yeah? If you don’t mind my asking, what’s the job?”

“Routine,” the redhead said, and when Harley looked over at the crew-cut guy, he, too, just stared down into his nearly empty mug and said, “Training mission.”

Then they kind of closed up like a clamshell, talking to each other in low tones, and Harley felt like a horse’s ass sitting there on the stool next to them. But he wasn’t about to get up and leave right away because that would make it look even worse. Instead, he sat there and finished his beer, trying to draw the bartender into conversation about the latest Seahawks game. But even Al was too busy to talk.

There was a boisterous laugh from the rear, back near the pool tables, and Harley saw it was from the husky guy in glasses, the one sitting between the tall, thin guy and Port Orlov’s illustrious mayor, Nika. Harley had never had a thing for native chicks – he liked leggy blondes, even if they were fake blondes like Angie – but for Nika, he had often told his pals Eddie and Russell, he would make an exception. She couldn’t have been more than five-three, five-four, with big, dark eyes and hair as black as a seal. But he loved the way she was built – trim and hard, and when the weather was good and she went around town in just a fleece jacket, with her long hair loose and whipping in the wind, he had to admit she got him going.

After putting away one more beer and hanging out by the jukebox like he cared what played next, he meandered back toward the pool tables. Selecting a cue from the rack, he pretended to be checking its tip and its straightness, and then, as if offhandedly, noticed Nika sitting a few feet away. “Hey, Your Honor,” he said, facetiously.

“Harley.”

“Want to run a few balls with me?”

“Another time.”

He was debating what his next move should be when the tall guy, with the remains of a burger and fries on the plate in front of him, saved him the trouble. “Is that Harley as in Vane?” he asked.

“The one and only. Accept no substitutes.”

“Frank Slater,” he said, rising enough to extend a hand. “I’m pleased to meet you. I heard about your ordeal.”

“Yeah, that’s what it was, all right.”

“Do you mind if I ask you a few questions?” he said, pushing out an extra chair. “I’m a doctor – it’s in our nature.” This was too good to be true, Harley thought, even if Nika did look like she was going to shit a brick. Harley turned the chair around so that he could lean his arms on the back as he sat down.

“This is Professor Kozak,” Slater said.

“Prof.” When they shook, the guy’s grip was like a vise – not like any professor’s that Harley’d ever heard of. Had to be a Russkie.

“I’m glad to see you look completely recovered,” the doctor observed. “No residual effects then?”

“Nah, I’m okay,” Harley said, though if the guy had asked about any mental effects, he could have told him a different story. Every time he closed his eyes, he had a nightmare about being chased by a pack of black wolves, only they all had human faces.

“You know, there’s something called PTSD – post-traumatic stress disorder – and it can hit you days, weeks, or even months, after something like what happened to you.”

Harley had seen enough TV shows to know all about it. “Yeah, yeah, I’ve heard.”

“I just wanted you to keep it in mind,” he said, “and let you know that you should see someone if you start having some problems dealing with the fallout. It would be completely normal if you did.”

Harley snickered. “Yeah, okay. If I start freaking out, I’ll just go and see one of the shrinks we don’t have, at the hospital that doesn’t exist.”

The doc nodded, like he knew he’d just made an ass of himself, but at the same time Harley felt this weird urge to take him up on the offer and get some of this crap off his chest – to tell him about the dreams of the wolves and the sight of somebody with a yellow lantern. It wasn’t like he could confess any of it to Russell or Eddie – they’d just tell him to have another beer – and even Angie would think he was acting like a pussy.

“You mind if I ask you a question now?” Harley said.

“Shoot.”

“What are you doing out here in the armpit of Alaska?” Glancing at Nika, he added, “No offense, Your Honor.”

“None taken. And you can knock off the ‘Your Honor’ stuff.”

He liked that it had gotten to her.

Slater bobbed his head, wiped up some ketchup with the last of his fries, and said, “Just some preparedness drills with the Coast Guard. Better safe than sorry.”

But his eyes didn’t meet Harley’s, and now Harley knew that something pretty big must be up, after all. Charlie’s suspicions were right; he might be an asshole, but he was smart. Harley would give him that.

“By the way,” Slater said, “what ever happened to that coffin lid that you rode to shore like a surfboard? I saw a photo of it in the paper.”

“Why?”

“Just curious.”

“As a doctor?”

Slater’s expression gave away nothing – and everything.

“I was thinking about putting it up on eBay,” Harley taunted. “But if you want to make me a cash offer …”

“Actually,” Slater said, “I was thinking along rather different lines. I was thinking that it doesn’t belong to you, and it ought to go back where it came from.”

“Oh yeah? Where’s that?”

“To the graveyard, on St. Peter’s Island.”

Then Slater looked straight at Harley, no bullshit anymore, and Harley could see he was dealing with more than some doc on a training run. So it was high time that the doc knew who hewas dealing with, too.

“Law of the sea,” Harley said. “I found it, it’s salvage, and it’s mine. And no one better fuck with me.” He stood up, pushing off from the chair. “See you around,” he said, before glancing at Nika and adding, “Your Honor.”

* * *

“I do not think I would trust that man,” Kozak said, as Harley stalked off. Finishing off his mug of beer, he plunked the glass down on the table and burped softly.

“I think you would be right not to,” Nika said. “Harley and his brother Charlie are both bad news.”

Kozak excused himself to head for the men’s room, and Slater asked her for the full rundown.

“We’d be here all night,” Nika said, “just going through the police blotter.” But she gave him the capsule description of the Vane family and its long history in the town of Port Orlov. He seemed particularly intrigued when she mentioned that Charlie ran an evangelical mission over the Web.

“So that explains the lighted cross above that house in the woods,” he said. “I couldn’t help but notice it from the chopper.”

“X marks the spot.”

“And you think he’s for real?”

That was a tough one, and even Nika was of two minds. “I think he thinks so. But can a leopard really change its spots? Underneath, I’ve got to believe that Charlie Vane is still the same petty crook he’s always been. You can judge for yourself tomorrow.”

“How come?”

“He’s sure to be at the funeral service for the crew of the Neptune II. The whole town will turn out.”

“I’m not sure the professor and I should attend.”

Nika laughed. “You might as well. I mean, if you think your being here is some kind of secret, you’ve never been to a town like Port Orlov. Harley’s probably bragging already about how he told you to stuff it. If he’s lucky, it’ll be a good enough story to get Angie Dobbs back into bed with him.”

“Who’s Angie Dobbs?”

“The town’s most eligible bachelorette,” Nika replied. “The blond waitress over by the jukebox.”

Indeed, Harley was loudly regaling her, and a couple of others, with some tale or other. Slater wryly shook his head.

“It sounds like you’ve got your hands full running this town.”

Nika shrugged; she didn’t want him to think she felt that way. But it was the truth, nevertheless. Port Orlov, like so many Inuit villages in Alaska, was a wreck. With far too few social services and way too many problems, there were times when she felt marooned in the wilderness. Even if the town could just manage to get a decent, full-time medical clinic, it would be a huge step forward, but try finding the money for it, much less a doctor to staff it. For all of her noble intentions, Nika only had two hands and there were only so many hours in the day.

“We make do with what we’ve got,” she finally said.

“Sometimes,” he sympathized, “the satisfaction has to come from knowing you’ve done all that you can. No matter what the odds.”

She had the feeling that he was talking about his own work, too, and she wondered what terrible scenarios he might be revisiting in his mind. He had the look of a man who’d seen things no one should see, done things no one should ever have to have done. And despite their differences – not to mention that fact that they’d gotten off to a bumpy start at the hockey rink – she was starting to feel as if Slater might prove to be a kindred spirit.

In a backwater like this, they weren’t easy to come by.