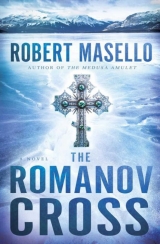

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Chapter 46

Anastasia awoke to the sound of screaming … her own.

Everything around her was black and silent and still, as if she’d been muffled in a cloak of the heaviest black mink.

Or buried in a coffin.

She screamed again, every inch of her body aching and sore, but when she threw out her arms, thankfully they did not collide with the boards of a casket and when she sat up nothing obstructed her head.

But where was she?

She heard hurried, furtive footsteps and then the sound of a door opening … but from the floor. Light spilled into the room from a kerosene lamp, raised through a trapdoor, and a woman’s voice urged her not to scream again.

“You are safe, my child. You are safe.”

A woman in a black nun’s habit clambered up the last rungs of the ladder and knelt beside the pallet she was lying on. “I’m sorry,” she said, “the lamp must have run out of oil.” Her face seemed vaguely familiar.

And now Ana could see a rickety table, with an extinguished lantern on it, and a ceramic bowl and pitcher. The ceiling was sharply slanted, and cobwebs hung from the rafters. She was in an attic … an attic that smelled of warm bread and yeast and honey.

“You are at the monastery of Novo-Tikhvin. A soldier, Sergei, brought you here.”

“When?” Her voice came out as a croak.

“Three days ago.”

Three days ago … and then it all came back in a flood, the late-night awakening, the innocent march to the cellar, lining up for the photograph to be taken … and the guards bursting into the room instead. The reading of the death sentence. Her mind could go no further before she broke down, racked with uncontrollable sobs. The nun, her face framed by the squarish black hat and the black veils that hung down on either side of her cheeks, consoled her as best she could, all the while counseling her to remain quiet.

“My family …” Ana finally murmured, “my family?”

But the nun did not reply. She didn’t have to. Ana knew. Just as she knew who this nun was now – her name, she recalled, was Leonida. Sister Leonida. It was she who had sometimes brought the fresh provisions to the Ipatiev house.

“The Bolsheviks are looking for you. They know that you escaped. So we have hidden you here, above the bakery.”

The monastery was almost as famous for its bread and baked goods as it was for its many good works. In addition to the six churches it housed within its grounds, the monastery was also home to a diocesan school and library, a hospital, an orphanage, and workshops where the sisters – nearly a thousand of them – painted icons and embroidered ecclesiastical garments with silken threads of gold and silver. Their work had long been considered the finest in the Russian Empire.

Sister Leonida said, “You must eat something,” and gathering up her skirts, carefully descended the ladder. She left the lantern beside the straw-filled mattress, and by its light Ana removed her blanket and inspected herself. She was dressed in a long white cassock – a rason—that the nuns and priests customarily wore under their outer robes; it went all the way to her feet and the sleeves were long and tapered to the wrist. The clothes she had worn that terrible night were gone – what could have been left of them after that fusillade? – but her corset, lined with the royal jewels, was draped across a chair. She wondered if the nuns had discovered its secret cache … the cache that only now, she realized, must have saved her life by deflecting the hail of bullets. Her ribs and abdomen were as sore as if she had been pummeled by a hundred fists, and there were fresh bandages on her shoulders and legs. Plucking the rasonaway from her breast, she glimpsed the emerald cross still resting against her bosom. Coarse woolen socks had been pulled on over her feet; she was reminded of Jemmy, her little spaniel, who used to sleep atop her feet at night, and another round of hot tears coursed down her cheeks.

When Sister Leonida returned, she brought a hunk of fresh brown bread and a bowl of hot lamb stew. Ana didn’t want it – her throat was so constricted with grief that she could not imagine swallowing – but Leonida urged her to eat. “You owe this to yourself, to your family … and to God. He has spared you for a reason.”

Had He? Yes, she had been spared, but to what did she truly owe that strange fate? She could recall the prophetic words of the holy man Rasputin … and though she wished she could forget it, she saw in her mind’s eye his ghostly image arising from the smoke in the cellar that night.

Once she had eaten enough of the stew to satisfy the nun—“I’ll leave the bowl here,” Leonida said, “and you can finish the rest when I bring you some of the honey cake that’s in the oven right now”—Ana asked after Sergei. “Do the Bolsheviks know he was the one who rescued me?”

The sister nodded. “He is in hiding, too. But I will get word to him that you are awake and recovering well.”

“Can he come to me here?” Ana wasn’t sure if she was asking for some unthinkable favor, or even possibly putting Sergei into some greater danger than he was already in. But she longed to see him.

“Eat,” the sister said, “and rest.”

Ana did not know how to interpret that reply but was afraid to push any harder. And truth be told, she was already fading back into a lethargy, retreating from everything she had already learned, needing to forget again … and to lose herself once more in the soothing abyss of sleep.

Chapter 47

It was with dread in his heart that Slater rushed to Nika’s tent. He couldn’t very well knock on the flaps, but he shouted above the wind that he was going to come in and that she should don her mask and gear.

What he saw beneath her goggles was a pair of frightened eyes. The bare lightbulb rigged overhead bobbed on its cord in the billowing tent.

“Let me see your hand,” he said, and like a dog with a wounded paw she held out her palm. With his own gloves he inspected the spot where the needle had punctured the skin. The mark was still evident, but so far it wasn’t inflamed or suspect in any way. A small relief, but not much more than that. The etiology and incubation period of this flu was uncertain, to say the least. “How are you feeling?”

“Scared,” she admitted. Her long black hair was tied in two glistening braids that hung down over her shoulders.

“We all are,” he said. “But it’s going to be okay, trust me.”

“How is Eva doing?”

“I’ve done as much as I can for her here.” Indeed, he had just changed her dressings, replaced several broken sutures, and administered stronger sedation. “But she’s going to be evacuated by chopper very soon. You’re going, too.”

“But I’m all right. If you need the space on the helicopter for—”

“I need you to help me track down Harley Vane and Eddie.”

“What are you talking about?”

As quickly as he could, he explained what he had learned, including the fact that Russell’s frozen corpse had been unearthed outside the church. Nika appeared incredulous.

“He was attacked by the wolves?” she said.

“No room for doubt on that score,” Slater said, before going on to explain what he thought the others had been up to on the island.

“Then there’s no way of knowing what they might have been exposed to?”

“No,” Slater said, “there isn’t. And they don’t know either.”

Nika, fully grasping the gravity of the situation, said, “But can they possibly have made it to shore in that boat? In these seas?”

“For argument’s sake, we have to assume that they did.”

“I should call the sheriff in town,” she said, starting for the SAT phone, but Slater put up a hand to stop her.

“He’s already been notified, and he’s been told what precautions to take for himself and his men.” Slater had also notified the Coast Guard, the National Guard, and the civilian authorities in the state capital of Juneau. What he needed was a tight ring to be formed around the town of Port Orlov, and a wider ring with a ten-mile perimeter to be formed around even that. Northwest Alaska, fortunately, was sparsely populated, and it wasn’t exactly crisscrossed with roads and highways; most of the travel was done by boat and air, and Slater had already arranged for the harbor to be blockaded and the commercial aircraft to be grounded. When he’d encountered any resistance, he’d referred the calls to AFIP headquarters in Washington. By now, he figured, Dr. Levinson was probably planning to put him in front of a firing squad when and if he ever got back.

“Frank,” Nika said, “what’s going to happen to the people in Port Orlov?”

“Nothing,” he replied. “We’re going to stop this thing in its tracks.”

“I just couldn’t bear it,” she said, still sounding fearful, “if what happened in 1918 happened again … and on my watch. I’m the mayor, I’m the tribal elder, I’m the one they trusted. I remember the stories of my people dying in their huts, the dogs feeding on their bodies for weeks.”

“That won’t happen,” he said, holding her hands in his gloves and wishing that he could just strip off all the protective gear – his and hers – and touch her for real.

“My great-grandparents passed down the stories. They were among the few survivors.”

“And God bless your ancestors, because that immunity might have been passed down to you, and others. We’re going to take every precaution,” he said, “just as we have to do, but we willcontain the threat.”

Unable to kiss her, or even touch the skin of her naked hand with his own, he bent his forehead to hers and rested it there. And though he was aware of how odd and even comical this scene would appear to any outside observer – a couple in hazmat suits, communing in a rickety, windblown tent – it was also the most intimate moment he had experienced in years. He closed his eyes – it felt like the first time he’d shut them in ages – and if it were not for the distant clatter of propeller blades, he might have stayed that way forever.

“Frank, do you hear that?”

He did. “Get your things together and be ready to go in five minutes!”

Outside, and wiping away the snow that stuck to his goggles, he looked up to see the blinking red lights of the Coast Guard helicopter as it skimmed over the treetops, then circled the colony grounds. Sergeant Groves lighted a ring of flares to mark the spot, and the chopper slowly descended, wobbling wildly and whipping the snow into a white froth. Slater didn’t even wait for its wheels to settle before charging up to the cabin door as it slid open.

“Follow me!” he ordered, and two medics, already swaddled in blue hazmat suits, leapt out into the storm carrying a metal-reinforced stretcher. At the church, Slater kicked the crooked doors ajar and barged inside, the wind blowing a gust of snow like a little tornado all the way down the nave toward the iconostasis.

“In here,” Slater said, stopping to rip open the makeshift quarantine tent.

Eva was barely conscious as he removed the IV lines, gave the medics the latest stats on her condition, and helped slide her onto the stretcher.

“Frank,” she mumbled, “I’m sorry …”

But the rest of her words were lost beneath her mask and in the commotion of her removal.

“You’ve got nothing to be sorry for,” he said, laying a hand on her frail shoulder.

The medics carried her carefully down the slanting steps and across the colony grounds to the landing pad. Slater saw Sergeant Groves and Rudy hauling the body bag with Russell inside it toward the cargo hatch, and as Groves undid the latches, the pilot jumped out of the cockpit to object to this unexpected and additional cargo.

Even over the howling wind, Slater could hear him shouting, “What the hell are you doing? I have no authorization for that!”

And for Slater it was suddenly as if he were back in Afghanistan, with a little girl dying from a viper bite. “I’m authorizing it,” he declared, and as the medics clambered aboard with Lantos, Nika appeared, ducking into the cabin like a shot. The pilot, even under his own gauze mask, looked confused about what to do about all this, but Slater set him straight. “And now we need to take off!” At such times, it was hard to remember that he wasn’t a major anymore, only a civilian epidemiologist, but he had learned that if he behaved like one, few people were prepared to question his commands. He climbed into the chopper to close any debate.

Seconds later, the props whirring, the helicopter rose into the air, buffeted this way and that as if a giant paw were batting it around; out the Plexiglas window, Slater could see Groves and Rudy, hands raised in farewell, and as he adjusted his shoulder restraints so that they weren’t squashing the little ivory bilikininto his chest – so where was the luck the damn thing was supposed to bring? – he spotted Kozak skidding into view, with the earmuffs of his fur hat blowing straight out like wings on either side of his head, and holding his thumbs up in encouragement. It was a good team, that much he had done right. Lantos groaned as the chopper dipped, then plowed forward, its nose down, soaring just above the timbers of the stockade and the onion dome of the crooked church.

Chapter 48

Sergei had never had any trouble going to ground. You could not grow up on the steppes of Siberia and not know how to live off the land and stay out of sight; it was bred into the bones of anyone whose ancestors had ever had to flee a Mongol horde, or hide from a rampaging pack of Cossacks.

But these days it was especially tricky. After he had safely delivered Anastasia into the hands of Sister Leonida, he had hovered around the town of Ekaterinburg, where great changes were under way – particularly at the House of Special Purpose. He had watched from the shadows as all signs and vestiges of the royal family were removed and burned in a bonfire in the courtyard. He could see the Red Guards overseeing local workers as they scraped the whitewash from the windows, scrubbed the obscene graffiti from the outhouse, brought in mops and brooms and buckets to clean out the charnel house in the cellar. And he had managed to forage through the trash in town and find a soiled copy of a local broadsheet, the text of which had no doubt been approved, if not written, by Lenin himself. The headline read, DECISION OF THE PRESIDIUM OF THE DIVISIONAL COUNCIL OF DEPUTIES OF WORKMEN, PEASANTS, AND RED GUARDS OF THE URALS, and the article contained the official party declaration: “In view of the fact that Czechoslovak bands are threatening the Red capital of the Urals, Ekaterinburg; that the crowned executioner may escape from the tribunal of the people (a White Guard plot to carry off the whole imperial family has just been discovered), the Presidium of the Divisional Committee in pursuance of the will of the people has decided that the ex-Tsar Nicholas Romanov, guilty before the people of innumerable bloody crimes, shall be shot.

“The decision was carried into execution on the night of July 16–17. Romanov’s family has been transferred from Ekaterinburg to a place of greater safety.”

A place of greater safety, he scoffed, crumpling the sheet in his hands. The bottom of a coal pit at a desolate spot called the Four Brothers.

But the paper was right about one thing – the Czechs and White Guards were indeed infiltrating, and overrunning, the area. Eight days after the massacre, Yurovsky and his Latvian comrades had had to make a run for it, and now that most of them were gone, Sergei had risked returning to Novo-Tikhvin late that same night.

“She is much better,” Sister Leonida said, ushering him through a back gate, “though, as you would expect, she is sorely troubled.”

“Can she be moved?”

“Why move her? She is safe here, lost among the many sisters.”

But Sergei knew better than that; he knew that the tides were always turning in war and that Ekaterinburg was destined to fall back into Red hands eventually. When it did, the monastery itself would probably be destroyed; Lenin had no love for religion.

Furthermore, for all he knew, Commandant Yurovsky – no fool – had figured out that he’d been cheated, that the youngest duchess might still be alive somewhere. No, there was only one place on earth where she would be truly secure, and Sergei was determined to take her there.

The nun led him into the bakery, unoccupied now but still warm and aromatic from the day’s baking, and silently pointed to a trapdoor in the ceiling. Then she discreetly left him to his own devices. Stepping atop a barrel of flour, he pulled the door down cautiously, unfolded its steps, and after climbing to the top saw Anastasia sitting at a small table in the corner of the attic, writing in a journal by the light of a kerosene lamp. Dressed in a black cassock with elaborate silver embroidery, and humming some melancholy tune under her breath, she didn’t hear him, but continued to scrawl across the pages of the notebook, her head down, her light brown curls grazing her shoulders. Despite everything that they had been through together, he was still shy – a rural farm boy, who felt himself nothing but elbows and knees and cowlicks when he was in her company.

But if it ever came to it, he would risk his life again to save her.

“Ana,” he said, and her head came up slightly, as if she had heard a ghost in the rafters. “Ana.”

And then she turned from the table, her gray eyes, once so filled with mischief and joy, now brimming with an ineffable sadness. She was not yet eighteen, but her expression betrayed the grief and fear of someone who had seen horrors no one should see and lived through nightmares no one should ever have had to endure. Her cheeks, once plump and rosy, were drawn and hollow, and her lips were thin and downcast.

“I prayed you would come back.” Even her voice was subdued, burdened.

Sergei closed the trapdoor behind him and went to kneel beside her at the table. She stroked his head as if she were the older woman – and here he was, twenty, just last month – but when he looked up at her, he could see how pleased she was to see him. “I was so afraid I would never be able to thank you.”

The back of her hand brushed the side of his face, and his skin tingled at her touch.

“Sister Leonida tells me you are recovering well.”

“They have been very good to me here.”

On the table he saw that there was a bud vase with several blue cornflowers in it, and he smiled. “Remember the day you gave me one of those?” He did not tell her that he had it still.

Ana smiled, too, and for several minutes they reminisced about only insignificant things – the flowers in the summer fields as the train had made its way into Siberia, the way Jemmy had loved to jump off the caboose and run in circles whenever they had stopped for coal, Dr. Botkin’s passion for chess (and how frustrated he was whenever young Alexei had brought him to a draw). Like so many of the Russian peasants, Sergei had been filled with a native reverence for the Tsar and his family – a reverence that the Reds had worked tirelessly to undermine and destroy. The bloody toll of the war had sealed the Bolsheviks’ argument.

But once Sergei had been exposed to the family itself, once he had seen the heir to the throne writhing in pain from a minor injury, or the Tsaritsa ceaselessly fretting over him, once he had heard the laughter of the four grand duchesses and watched the melancholy Tsar pace the length of the palisade at the Ipatiev house, he had changed his mind again. Now they were not just iconic figures to him, the bloody puppets that Lenin had made them out to be, but real people … people that the staretsof his village, at one time the most famous man in all of Russia, had befriended.

Was Sergei going to listen to a prophet from his own town – a man of God, touched with holy fire – or Lenin, an exiled politician that the Germans had smuggled back into the country in a secret train, purely to foment rebellion?

“How have you stayed safe?” Anastasia asked, and Sergei told her how and where he had been hiding out in the surrounding countryside. In July, it could be done; later in the year, it would not have been so easy.

“And does the world know …” she said, faltering, “about what happened to my family?”

He told her what he’d read in the broadsheet, including its bold lie about the safety of the family, and a flush of fury rose in her cheeks.

“Murderers!” she exclaimed. “And cowards, too – afraid to admit to their crimes!”

Sergei wondered if that was what she had been writing about in her journal.

“I will tell the world! I will shout it from the rooftops, and I will see those murderers hang!”

Sergei was hushing her when he heard what sounded like a broomstick banging on the bottom of the trapdoor. Sister Leonida must have been keeping guard in the kitchen down below.

“Someday,” he said, trying to calm her, “you will do that, and I will help you. But that day is still far off. You have enemies, and you have already seen what they can do. Now is not the time for that, Ana.”

Breathing hard, she subsided. “What is it the time for then? Hiding in this attic like a little mouse?”

“No, not that, either.” This was as good an opportunity as he was likely to get to broach the subject he had been meaning to introduce. “Now is the time to leave, with me, for the place Father Grigori himself prepared as a refuge. It was part of the vision he had before his death.”

Ana remembered well many of Rasputin’s predictions … all of which had so far come true – even, to her sorrow, the most dire.

“It is a colony on an island, and many of the faithful are already there. I remember the day they left Pokrovskoe, led by the Deacon Stefan. You won’t be safe until you are out of the country and hidden in a place where no one can find you.”

She did not appear persuaded, but she was still listening. “Where is this secret place?”

“A long way east of here, across the steppes.”

“And how do you propose we get there?”

Sergei had spent many hours mapping it out in his head, figuring out where they could board, under assumed names, the recently completed Trans-Siberian Railway, and how far they could take it eastward. When it detoured to the south, they would have to disembark and find a way to continue northward. At some point, they would have to find a pilot, with a plane, willing to take them across the Bering Strait. The right price, he had learned, made anything possible, and payment was the one thing he knew would not be an obstacle. Even as he had carried Ana’s limp body through the woods, he had glimpsed the cache of precious jewels sewn into her corset. A bauble or two from that tattered lining and he was confident that he could secure whatever transportation they might need. But instead of outlining the plan in any detail for her now – there would be many weeks to do that – he simply gestured at the emerald cross around her neck and said, “I have read the inscription on the back.”

Anastasia blushed, as if he’d caught her stepping out of the bath.

“His blessing has protected you so far,” Sergei said. “Why would it end now?”