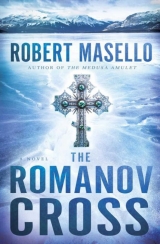

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Chapter 53

Charlie’s mind was churning. He hadn’t seen a single other vehicle moving on the highway in either direction, but on a night like this, who in his right mind would be out? Only long-haul truckers would brave it, and that was only because they had to. The snow was coming down so fast, the windshield wipers were having trouble handling it, even at their top speed.

Glancing into the rearview mirror, he saw Harley huddled in the backseat, and if he thought he looked sickly before, it was worse now. His forehead was beaded with sweat, his eyes had a weird glaze, and his fingers kept picking at that damn wound on his leg; all Charlie knew was that he must have gotten into some mean shit on that island. Mean shit, which was probably infecting the whole car by now. He’d have to tell Rebekah and Bathsheba to scrub down and sanitize the whole van once he got back to Port Orlov.

With the back of his hand, Charlie checked his own forehead, and he was as cool as a cucumber. Didn’t have a cough or anything else, either. At least not so far. But if Harley didhave something contagious, and he gave it to Charlie, there was going to be hell to pay.

A sign flashed by in the darkness, saying NEXT FOOD AND FUEL—50 MILES, and Charlie glanced at the gas gauge; he had about half a tank left, but with the extra canisters in the back he could easily make it to Nome without stopping. He didn’t want to risk using his credit card at a service station, or showing his face at a diner. One thing he’d learned was, people remembered the guy in the wheelchair, and just in case anyone came along trying to follow his trail, he didn’t want to leave any more clues than he had to. Let ’em guess what the Vane boys were up to.

In a weird way, he found it exhilarating to be out on the road like this. It reminded him of his former life, before he’d given himself over to the Lord. When they weren’t out crabbing, he and Harley had always been off running some scam, or hijacking somebody’s boat, or burglarizing some rich bastard’s vacation home. He knew now that what he’d been doing was wrong, that he was breaking the third, or was it the fourth, commandment, the one about not stealing, but he also knew that he’d felt a rush nothing else could come close to. These days, when he was preaching and really getting into it, really feeling the Presence of the Lord, it was sort of like that.

But if he was completely honest with himself, it still wasn’t as good as cracking open somebody’s wall safe and finding a stack of hundreds inside. Why was that? It was something he would have to take up with Jesus during his next heart-to-heart.

Fumbling inside his coat, he pulled a cigarette and a Bic lighter out of his shirt pocket. With the women gone, he could sneak in a smoke. He inhaled deeply, and dropped the lighter on the passenger seat. Funny, how a cigarette could make your lungs feel bigger even as, in actual fact, it shrunk ’em up.

A gust of wind slapped the side of the van so hard it roused Harley from his stupor. “The icon,” he said, in a worried voice, “what did you do with it?”

“It’s right here in the glove compartment. Same as the cross.”

“I need it.”

“What for?” Charlie couldn’t tell if his brother was in his right mind or not.

“To save me.”

Now he knew. “How’s it gonna save you, Harley?”

“It’s got the baby Jesus on it. Jesus saved you, right?”

“Yes, He did. But you don’t need an old icon for that.”

“I do,” Harley croaked. “I need something ’cuz I’m gonna die tonight.”

Charlie had never heard his brother say anything like that, not ever, and when he looked in the rearview mirror again, he saw that Harley’s eyes were burning like black coals and his whole head was shaking.

“Nobody’s dying tonight,” Charlie said. His mind went back to the night he’d seen – imagined – the hollow-eyed man in the long coat, reaching for the cross from the backseat. He didn’t care how much this Russian stuff was worth anymore – he was starting to wish he’d never laid eyes on any of it. “As soon as we get to Nome, we’ll take you to a doctor. Get you fixed right up.”

The road was veering now, as it began to track along the rim of the Heron River Gorge. Normally, that alone – the site of the accident that had left Charlie a paraplegic for life – was enough to rattle him, even if all this other crap hadn’t been going on.

But it wasgoing on, which made his apprehension just that much worse.

A sign said the bridge was coming up ahead. Huge, snow-covered hunks of granite, left by ancient glaciers, lined the shoulders like train cars waiting to be hitched.

“There’s not enough time,” Harley said. “Give me the icon now.”

“I can’t reach over that far. I’ll get it for you once we cross the bridge.”

“Too late,” Harley said, with chilling certainty. “That’ll be too late.”

The van rocked and swayed as it hit a stretch of asphalt buckled from frost heave. Every year, the highway department had to come out in the spring and repair the damage done in the winter. Once in their youth, Charlie and Harley had tried to make off with one of their road graders, before realizing that its top speed was about ten miles per hour.

The gorge cut a deep swath through the land for nearly nine miles, and the bridge over it had been built at the narrowest spot available, between two rocky bluffs. He kept a close eye on the road, which was rapidly disappearing under a shifting scrim of snow and ice. Even with four-wheel drive and chains on his tires, he was losing traction now and then. His brother moaned, and when he glanced in the rearview mirror to check on him, what he noticed instead was a tiny pinprick of light, way down the road behind them.

A tiny pinprick that was moving.

“Harley, quit your moaning and turn around!”

“Why?”

“Just tell me what you see down the road!”

The blanket still wrapped around his shoulders, Harley turned and looked.

“Looks like a headlight. Maybe just a motorcycle.”

Charlie studied the tiny light, and damn if it didn’t look like it was a single headlamp after all. But who’d be trying to navigate these dangerous roads, in the middle of a blizzard, on a motorcycle? That’d be crazy. Cops would be using a heavy-duty cruiser, the National Guard guys would be in a jeep. The only thing he could tell for sure was that it was moving along at a good clip.

“Keep an eye on it,” Charlie said, turning off the cruise control and pushing the accelerator lever.

“Shit. What if it’s Eddie on a snowmobile?”

He heard the click of a safety being taken off a gun. A Glock 19, from the sound of it. Oh, Christ, Harley was not only nuts … but armed?

“Where’d you get that?” Charlie demanded, though it had undoubtedly come from his own gun cabinet. “Put it away. Now.”

But Harley was off in his own delusion again. “Fuckin’ Eddie,” he muttered, staring out the back of the van.

“Eddie’s dead. You told me so yourself.”

Harley, still staring, clucked his tongue and said, “Eddie never did know when to call it quits. I never should have let him come back with me.”

Come back?Charlie thought Eddie had fallen off a cliff on the island.

“Well, this time I’m going to cap his ass for good.”

Charlie stopped trying to make sense of Harley’s ravings. All he could do was drive … and pray he got to Nome before Harley went off in his van like a bomb.

Chapter 54

Stepping into the tavern, Ana was careful to remain behind Sergei. Dressed in rough old clothes, her hair chopped short, and her eyes downcast, she appeared to be the perfect peasant wife, beaten into subservience and silence. After so many weeks on the run, it was an act she was finally growing used to.

Sergei, in a brown-wool tunic buttoned all the way up the side of his neck, and a black sealskin coat, furtively scanned the tavern and its occupants. A couple of dozen men in leather jackets were playing cards and dominoes and swigging from bottles of beer and vodka. A fire was crackling in the immense hearth, and gas lamps burned along the walls. A phonograph on the bar played a scratchy version of the country’s newly inaugurated anthem, the Internationale; every note of it made Ana want to smash the record.

Sitting alone at a table in the corner, a bald man in a pilot’s uniform raised his chin in acknowledgment. Sergei and Ana threaded their way through the cluttered room, drawing a few glances and a couple of coarse remarks about the rubes, before drawing up chairs at the table.

“You are Nevsky?” Sergei asked in a low voice.

The bald man didn’t answer but motioned to the innkeeper to bring two more glasses. Above the bar, a placard promoting the Imperial Russian Air Force had been defaced, and written in red paint on the wall beside it was the new name for the Soviet air force – the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Air Fleet. The bald man had several bright medals and ribbons pinned to his shirt.

The innkeeper plunked the glasses down on the table, filled them from a brandy decanter, and said, “Your bill is overdue, Nevsky.”

“I’ll pay it after you’ve shot down your first enemy fighter,” Nevsky said in a hoarse grumble.

The innkeeper grunted in disgust, and went back to the bar.

“And who is this?” Nevsky said, gesturing to Ana.

“My wife.”

“I wasn’t told there would be two of you,” he said, trying to stifle a cough.

“What difference does it make? The airplane can carry one more passenger, can’t it?”

Nevsky threw down a shot of the brandy. “Not for the same price it can’t.”

Ana wasn’t surprised. Although she kept her composure and said nothing, this was the same story they had encountered throughout their journey from the monastery at Novo-Tikhvin. They had been forced to bribe everyone, from wagon drivers to lorry loaders to ticket agents on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Everyone in Russia had his hand out, and nothing could be done or had without some special compensation being offered. The entire nation was starved and desperate and teeming with violence, and much as she tried to find some sympathy in her heart for these people – the people her own father and mother, despite what was said about them, had held so dear – she could not. In every soldier and peasant she encountered, she saw nothing but another murderer.

“What is the price then?” Sergei asked.

“Double. What else would it be?” He refilled his glass. “Do you take me for a thief?”

Sergei didn’t even have to look at Ana for approval; funds were the one thing they had. “We’ll pay it, but only after you take us to the island.”

“And only after you show me that you actually have it,” Nevsky said, pointedly looking Sergei up and down. The sealskin coat was weathered, his tunic was soiled, his boots were worn. Nevsky appeared dubious.

Sergei turned slightly toward Ana, and she pulled from under her full skirts a drawstring pouch. Sergei took it into his own lap, and with his hands concealed beneath the scarred tabletop removed two white diamonds the size of teardrops. He held them in his palm as Nevsky craned his neck to look under the table and see.

“One of them now,” Nevsky said, “as the down payment.”

Sergei gave it to him, and after looking around the room to see that no one was watching, Nevsky took a good long look at it and rolled it between his fingers. Satisfied, he wrapped it in his red handkerchief and stuck it in the pocket of his shirt. Then, leaning back in his chair with a skeptical expression, he said, “But where would someone like you have come by something like this?”

It was a question Sergei and Ana had been asked before.

“The Winter Palace,” Sergei confided, as if ashamed of his own actions.

“The Tsar’s treasures belonged to the people,” Nevsky said, feigning indignation and coughing into the back of his hand. “When the Winter Palace was stormed, that loot belonged to the proletariat.”

“I am part of the proletariat,” Sergei replied, and at this Nevsky laughed.

“An enterprising one, I’ll say that for you.” Then, leaning close, he explained that Sergei and Ana were to meet him at the airfield as soon as it was light out. “Keep behind the hangars, and for God’s sake, don’t call any attention to yourselves. Don’t bring anything heavier than a handful of straw. The plane won’t carry any more weight.”

That night, in return for an exorbitant charge to the innkeeper, Sergei and Ana bedded down between the beer barrels in the cellar of the tavern and waited anxiously for the dawn. Ana had never been in an airplane before, and she was quite sure Sergei had never been, either. She didn’t ask him because she knew he liked to pretend to be more worldly and experienced than he was, although, in her eyes, he was just a boy – a gangly creature with loose limbs and a cowlick and a long face that reminded her of her favorite pony. And she loved him.

Not only because he had saved her life – though wouldn’t that have been enough? – but because his heart had remained pure and righteous. She loved him for his innocence, for his devotion … and because he loved her in turn. Ana had lived a life of extravagant luxury and immense privilege, but she had also been cloistered and cosseted and confined, and it was only in the past year, when all of that had been stripped away, that she felt she had learned so much of what life was really like. Father Grigori had always told her she had a special destiny – the emerald cross beneath her blouse attested to the unbreakable bond between them – but only now did she feel she might be moving toward such a thing, whatever it might turn out to be. And without Sergei, she would never have escaped the makeshift graveyard at the Four Brothers, where everyone else in her family lay.

It sickened her that the official Soviet press still claimed that only her father had been shot and the rest of the family was safely sequestered somewhere. Once she made it to freedom, even if that freedom was only an island in the middle of the Bering Sea, she would find a way to expose these butchers for what they were.

It wasn’t yet dawn when Sergei nudged her. She doubted that he had been able to sleep any more than she had. They gathered their few things together in a bundle and crept up the stairs from the cellar. The innkeeper in a nightshirt was lighting a fire in the grate and pretended not to see them. Outside, the air was frigid, but the sky was lightening enough that she could see there wasn’t even a wisp of a cloud in any direction. Surely this would be good weather for the flight to St. Peter’s Island. The thought of being in a place, no matter how barren and remote, where she could openly be herself, where she did not have to fear every encounter and dodge every stranger, where she would be embraced by friends and followers of Father Grigori, promised such relief that it eradicated any fear she might have had of boarding the plane.

By the time they got to the hangars, the plane, with a red star freshly painted on its nose, was already on the runway. Nevsky, a leather cap clinging to his bald head and tinted goggles hanging down around his neck, was circling it, checking the tires and the struts and the wings. There were two wings, a wider one above the tiny cabin and a shorter one below, connected by a latticework of wires, and a long tail that reminded her of a dragonfly. It looked to her almost as flimsy as a dragonfly, too, and she could hardly imagine it carrying them for miles over an icy sea. Sergei had stopped where he stood, and was staring at it with slack-jawed wonder and evident dread, when Nevsky noticed them and, taking a quick look around the empty field, waved them over.

“Come on,” Ana said, taking Sergei by the arm and drawing him out of the shadows of the hangar. “We have to hurry.”

Nevsky was holding open the small door to the cabin, and he frowned when he saw their bundle. “What did I tell you about the weight?” he said, taking the bundle in hand, gauging it, then grudgingly tossing it onto the cabin floor. “Get in!” he ordered, coughing, then spitting a wad of phlegm onto the tarmac.

Bending double, Ana crawled through the dented metal door and sat bolt upright on a padded plank with the bag wedged under her feet; she could barely move since, in order to keep the bundle light, she had worn the corset freighted with jewels under her coat. Sergei, his eyes wide as saucers, got in and sat on a plank opposite. The space was so small, and his legs were so long, their knees touched. Ana gave him an encouraging smile, but he looked like a lamb being led to the slaughter.

Grunting, Nevsky crawled into the cabin, latched the door behind him, and squirmed into a seat at the front of the plane; it was shaped like a bucket and cushioned by a Persian rug folded double. With thick but nimble fingers, he began turning dials and flicking switches and doing all manner of things that Ana could not fathom. What she did understand was the machine gun firmly mounted at his elbow, and aimed through an aperture in the windscreen. The sight of its black barrel and deadly snout reminded her that this plane had been designed for aerial combat, not for ferrying refugees. It was built to dispense death, not life … like everything the Bolsheviks put their hand to.

“There are straps,” Nevsky said, over his shoulder. “Fasten them under your arms and around your waists.”

Ana found the straps hanging like reins in a stable from the sides of the cabin, and did as she was told; the clasp, she could not help but notice, was embossed with a double eagle, the old insignia of the Russian Air Force. Sergei’s fingers moved mechanically as he strapped himself in; his eyes were riveted on the floor, which appeared to have been cobbled together with sheets of steel, then sealed with a coat of tar. The whole compartment felt too insubstantial to withstand the rigors of a rough road, much less flight.

But the propellers, a pair on each side, suddenly engaged, and as the sun came fully into the Siberian sky, Nevsky piloted the plane onto the runway, shouting back to them, “Hold on!” But to what, Ana wondered? There was a roar from the engines, and a rumbling from the tires as they bounced across the ground. Sergei’s eyes were closed, and he was as rigid as a stick, his head back against the wall of the fuselage. His lips were moving in what was no doubt a prayer. The roar grew louder all the time, and the cabin rocked and creaked and swayed, and at any moment Ana would not have been surprised to see the whole contraption explode. Looking over Nevsky’s broad shoulders, she saw the tundra hurtling past, so fast it was only a brownish blur now – how could anything move at such a speed? she thought – and Nevsky pulling back on an oak-handled throttle that reminded her of one of Count Benckendorff’s canes. The speed increased, the roar of the motors became deafening, and just when she thought the shuddering plane was sure to fall apart, the nose tilted up ever so slightly, the jouncing abruptly stopped, and to her amazement she saw the ground falling away. The windscreen blazed with shards of orange light, and she wished that she, too, had a pair of the tinted goggles Nevsky was wearing. There was the strangest sensation in her stomach, as if it had just dropped into her shoes, but it wasn’t unpleasant; it was like the times Nagorny, Alexei’s guardian, had swung her so high on the garden swing that she had stopped at the top, afraid she was about to spill over the bar, before swooping back down instead. In her head, she could hear Alexei begging to be swung that high, too, and his delighted screams when Nagorny complied.

The grief overwhelmed her again, as it often did, like a crashing wave.

But Sergei’s eyes were open now. He refused to look out through the window, but gave Anastasia a wan smile. She reached across and squeezed his hand.

“We will be flying northeast,” Nevsky shouted, his words carried back to them on a cold draft. “This damn sun will be in our eyes the whole way.”

Ana liked it – she liked the hot bright yellow light, she liked the sky around it, a cerulean blue unmarred by a single wisp of cloud, and she liked it when the dark, snow-patched ground dropped away altogether, replaced by the cobalt blue of the Bering Sea. Glaciers sat serenely in the choppy waters, a pod of breaching whales gamboled among the chunks of floating ice. The horizon was a gleaming orange line, pulled tight as a stitch, and somewhere ahead there lay an island that was no longer a part of Russia at all, an island that housed a small colony of believers. A small colony of friends.

She would have liked to talk to Sergei, if only to distract him, but the howling of the wind and the din of the propellers was too great. Instead, she made do with holding his hand and gazing out at the unimaginable spectacle through the cockpit window. What a pity it was tainted by the machine gun, black, gleaming with oil, and brooding like a vulture.

When the plane banked, she was pressed back against the wall – it felt like lying on a slab of ice – and this time the sensation in her stomach was not so easily dismissed. The plane was losing altitude, she could feel it, and for a second she worried that they were going to crash, after all. Glancing out the window, she saw that the world had tilted to an odd angle, and in the distance, she could see two islands, not one, both of them flat and gray and barely rising above the sea. One was much bigger than the other, and she wondered which of them was St. Peter’s. Neither looked especially welcoming.

The angle grew even more extreme, and the engines made a louder, grinding sound, as the plane descended even more, soaring across the channel that narrowly separated the islands, and the windscreen filled with the image of the bigger of the two. Gradually, the plane leveled off, and the coastline appeared. Rugged, barren, choked with coveys of squalling birds. Anastasia caught a glimpse of a collection of huts, clustered on the cliffs above an inlet, as the plane dropped onto a cleared field, its tires bouncing up again as they touched the ground. The propellers whirred down, and Nevsky clutched the throttle with both hands, pulling back on it as if he were subduing a stallion. The cabin rattled, the tires squealed, and only the machine gun remained motionless. For several hundred yards, the plane rumbled and rolled along the tundra, before the engines stopped growling and the propellers stopped spinning and everything came to a halt.

Nevsky, pushing the goggles onto the top of his head, turned in his seat and said, “You can unfasten those straps now.” Then he coughed into his handkerchief.

Ana and Sergei undid their straps, and with trembling fingers Sergei unlatched the little door. He clambered out onto the ground, then held out a hand to help Ana. When she bent over, the corset nipped at her ribs, and her feet felt so unsteady she nearly toppled over. Sergei propped her up as Nevsky disembarked. Without a word, he went to a tiny, falling-down shed, and came out lugging two gas cans, one in each hand.

Ana, bewildered, looked all around, but apart from the shed, there was no sign of any habitation nearby, or any people. Were those huts the entire colony? Her heart began to sink. And why was there no one there to welcome them?

Nevsky seemed to be studiously avoiding them, and when Sergei ventured a question, he brushed him off and said, “Let me finish with this first,” as he poured the second can of gas down the funnel he had inserted in the tank at the rear of the plane. When that was done, he returned to the shed, came out with two more, and poured them in, too. A brisk wind was cutting across the open field, and Ana huddled in the shelter of the fuselage.

Tossing the empty cans to one side and removing the funnel, Nevsky finally turned to them and said, “I’ll have that second diamond now.”

“Where is everyone?” Sergei said.

“They’ll be here. Now, where is it?”

Sergei looked uncertain, but when Ana nodded, he gave it to him. Nevsky tucked it into his pocket, and threw open the little door to the plane. Then he jumped in, threw the latches, and only appeared again through the window of the cockpit. Sliding the window panel open, he spoke across the top of the machine gun as Ana and Sergei gathered below.

“Right now you’re on what the Eskimos call Nunarbuk.”

“You mean that’s their name for St. Peter’s Island?” Sergei said.

“St. Peter’s Island,” Nevsky said, fitting his goggles back into place, and pointing due east, “is over there.”

“That’s where we paid you to take us!” Ana cried, but Nevsky just shrugged.

“They have no landing strip,” he said.

“Then you have to take us back with you!” Sergei demanded, hammering at the side of the plane.

“Watch out,” Nevsky said, as he started to close the window. “The propellers can cut you in half like a loaf of bread.”

A moment later, Ana heard the engines revving up. The propellers clicked and twitched, then began to turn, and Sergei had to duck back away from the plane. It bumped along the ground in a wide circle, protected by its four whirling blades, before quickly gathering speed and then, as they watched in shock, altitude, too. It was only as it rose high into the sky, shining in the sun and banking slowly toward Siberia, that Ana realized they had even forgotten to retrieve their bundle from under the seat.