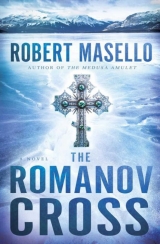

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

PART TWO

Chapter 12

“We’ll be coming up on St. Peter’s Island in about ten minutes,” the pilot said, his voice crackling over Slater’s headphones; even with the phones on, the rattling of the propellers and the thrumming of the twin engines on the Sikorsky S-64 Skycrane made it hard to hear. “I just wanted to make sure you guys got a good look at the place before the light goes.” On the horizon, the sun was a copper dollar sinking below the hazy outline of eastern Siberia. “We don’t get much daylight at this time of year.”

“In Irkutsk, I had sunlamps,” Professor Kozak said into his own microphone. “Three,” he said, holding up three gloved fingers for Slater to see. “One in every room.”

Slater nodded amicably, balancing a sealed envelope on his lap. The two men were packed in shoulder to shoulder behind the pilot and copilot, and flying over the icy, teal-blue waters of the Bering Strait; below them, the Pacific and Arctic Oceans converged, and the International Date Line cut an invisible line between Little Diomede Island, which belonged to the United States, and Big Diomede, which was Russian territory. While Sergeant Groves was back in Nome, organizing the rest of the cargo and waiting to shepherd Dr. Eva Lantos on the last leg of her journey from Boston, Slater had decided to go on ahead in the first chopper, along with his borrowed Russian geologist. There was no time to lose, and he wanted them both to get a good look at the lay of the land on St. Peter’s. Many decisions, he knew, had to be made, and they had to be made fast.

It had been an arduous and complicated trip already. Slater had flown from D.C. to L.A. to Seattle before catching a flight to Anchorage, and from there hopping on a supply plane to Nome, where the two helicopters were being loaded with the mountain of equipment and provisions the expedition would require. When the first one’s cargo bay had been filled, with everything from inflatable labs to hard rubber ground mats, then securely locked down, Slater and the burly professor, who hadn’t seen each other since picking their way across a minefield in Croatia, climbed aboard.

Unlike most helicopters, the Sikorsky was designed chiefly for the transportation of heavy cargo loads – up to twenty thousand pounds – and as a result it looked a lot like a gigantic praying mantis, with a bulbous cabin dangling up front for the pilots and passengers (no more than five people at a time) and a long, slim cargo bay with an extendable crane for lowering, or lifting, supplies from great heights. Two rotors – one with six long blades mounted above the chassis, and the other propping up the tail – kept it airborne. To Slater, it felt a lot like traveling in a construction vehicle.

For many miles, they had traveled along the rugged coastline of Alaska and over vast stretches of overgrown taiga, where aspens and grasses and dense brush thrived, and barren tundra where the soil was more unforgiving. Now and then he could make out polar bears lumbering across the ice floes, or caribou herds pawing for lichen buried beneath the frost. As they passed over a swath of land extending out into the sea, Slater tapped the copilot on the shoulder and pointed down at the gabled rooflines and crooked fences of a small town.

“Cape Prince of Wales,” the copilot said. “Founded in 1778.”

“By Captain Cook,” Professor Kozak said, proud to pitch in.

There wasn’t much to see, and at the rate they were going – roughly 120 miles per hour – the tiny town, cradled by a rocky ridge, was already disappearing from view. But Slater knew its sad history well. It wasn’t so different from that of its neighbor, Port Orlov.

Called Kingigin, or “high bluff” by its native inhabitants, it had once been a thriving Eskimo village and a lively trading post for deerskins, ivory, jade, flint, beads, and baleen. On the westernmost point of the North American continent, lying just south of the polar circle and with nothing but a dogsled trail leading to it from the mainland, the town should have been as safe from the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 as any place on earth. There wasn’t even a telegraph connection. But through a series of calamitous events, Wales, like a handful of other Alaskan hamlets, wound up suffering the highest mortality rates in America.

In October of that year, the steamship Victoriasailed into Nome, and the city’s doctor, aware of the danger, met the ship at the dock, where he insisted on examining the passengers and crew; he even went so far as to quarantine several dozen at Holy Cross Hospital. But when only one of them got sick after five days there (and even that illness was chalked up to tonsillitis), the doctor permitted the patients to be released. A hospital worker died of the flu four days later, and within forty-eight hours the whole city of Nome was placed under quarantine.

But by then the damage had been done. Mail had been unloaded from the ship, and even though every shred of it had been fumigated, the sailors who handed the bags to the local mail carriers had been unwitting bearers of the virus. Now, the mailmen, too, riding their dogsleds to every far-flung outpost in the territory, acted as the plague’s deadly agents. Wherever they went, they brought with them the contagion, and by the time rescuers reached the village of Wales, three weeks after the mail had been delivered, they found scenes of utter devastation – decaying corpses piled in snowdrifts, packs of wild dogs tearing at the remains. In one hut, a man was found with his arms wrapped around his stove, frozen solid, and he had had to be buried, still kneeling, in a square box. The survivors were found starving, drinking nothing but reindeer broth, in the one-room schoolhouse.

“Look at that!” the professor exclaimed, pointing to Cape Mountain now passing below them. “That, my friend, is the end of the Continental Divide.” His breath reeked of spearmint gum, which he was chewing assiduously to keep his ears from getting plugged.

A jagged brown peak, slick with snow and ice, Cape Mountain sat atop a gigantic slab of granite, shaped like an axe. The natives liked to say that the slab was the spot where Paul Bunyan had put his hatchet down, after he’d chopped down every tree in the Arctic. Slater could see how the legend got started.

“When we get to St. Peter’s,” the pilot said, “I’ll come in from the east, do a complete three-sixty, then we can hover wherever you want.” He consulted the fuel gauges, then added, “But not for long.”

At the thought of finally seeing the island, Slater felt his heart race, and he straightened up in his seat, which wasn’t easy given the bulk of the parka he was wearing and the over-the-shoulder restraints. The professor didn’t leave him much room, either, but he was enthusiastic company, and for that reason alone, Slater knew he’d picked the right man for what could prove to be the very bleak job ahead.

As the chopper approached, Slater could see – straight ahead and framed between the pilots’ shoulders – a gnarled hunk of black stone, surrounded by jutting rocks that broke the surface of the roiling waters. Its foundation was largely obscured by ice and mist. Slater could see snatches of beach, though they looked too steep and small for a helicopter, much less this one, to land on. Chiseled into the stone cliff, there appeared to be a winding set of steps.

“That whole island, it is from a volcano,” the professor observed over the headphones, admiringly. “Basaltic lava, two million years old.” He took off his spectacles, blew some dust from the lenses – filling the cabin with the scent of spearmint again – then hastily put them back on.

The chopper banked to the right, and now Slater got a better view out his own side window. Steep cliffs, dotted with nesting terns, rose to an uneven plateau, raggedly forested with deep green spruce and alders.

“Can you get closer?” Slater asked.

“Will do,” the pilot replied, “but the winds get tricky around the cliffs.”

The chopper descended and made a closer pass. But that was when Slater suddenly saw something, camouflaged by the patchy forest, which made him grab Kozak’s sleeve and point down.

An onion-shaped dome, made of rough timber and pocked with holes, poked its head up through the trees.

“The Russian colony,” the pilot said, circling.

Although the helicopter was buffeted by nasty crosswinds, the pilot was able to hold it steady enough that Slater could get the lay of the land. The old church was surrounded by several other ramshackle structures – old cabins teetering on their raised foundations, empty livestock pens, a well with a rusted bucket. A stockade wall, partly dismantled, enclosed what was left of the village.

But where was the cemetery?

The same thing must have occurred to the professor, who plucked at Slater’s sleeve and pointed off toward a trail leading away from what was once the main gate. It disappeared into a dense grove of evergreens.

“Could you move west?” Slater requested, and the pilot said, “Roger. But we’ve only got a few more minutes before we have to head into Port Orlov for refueling.”

The Sikorsky turned, its propellers churning even more loudly in hover mode than they did when flying, and followed the trail over the tops of the trees, until a rocky promontory appeared below. It jutted out from the plateau like an ironing board, its windswept ground dotted with old wooden crosses, toppling over, and gray-stone slabs.

It made sense, Slater thought. The graveyard had been sited as far from the colony as possible.

And in the gathering gloom, he saw a ragged spot at the very end of the promontory, where the earth and stone hung precariously above the cliffs, as if a limb had been ripped away from the body of the island … and now he knew precisely where the coffin found floating at sea had originated.

“Lights out,” the pilot said, and the last rays of the sun vanished as abruptly as a candle’s flame being snuffed. Darkness descended over the island, and the helicopter swiftly banked away from the steep, unforgiving cliffs.

But one question remained in Slater’s head. This had been possibly the most isolated colony on the planet, surrounded by ice floes and rocky coastlines, with no mail, and no intercourse with the locals. It should have been the safest place on earth during the 1918 pandemic. But even here, the Spanish flu had managed to insinuate its deadly tentacles, and he wondered if he would ever find out how. Not for the first time, he felt a flicker of grudging admiration for his terrible foe. Damn, it was wily.

“Those are crabbing boats below,” the pilot observed, as Slater looked down to see their running lights bucking in the choppy seas. “Worst job in the whole world.”

Funny, Slater thought. He had often heard his own job described that way.

Chapter 13

ST. PETERSBURG

December 25, 1916

The Winter Palace was never more beautiful than when it was done up for the Christmas Ball. Anastasia looked forward to it every year – particularly in a year as tragic and bloody as this one had been. Although millions of ill-equipped Russian soldiers were still desperately fighting the Germans along the far-flung borders of the empire, here, tonight, you would never know it. As she gazed down at the vast, snowy forecourt, hundreds of sleek carriages and gleaming motorcars, jingling sleighs and bright red troikas, drew to a halt in front of the massive entry hall of the palace, and the Tsar and Tsaritsa’s guests, decked out in all their finery, disembarked, laughing and chattering among themselves. Even from the window seat in her room, the young grand duchess could catch some of their exchanges – most of them spoken in French as it was so much more fashionable than Russian – and spot some of the more familiar faces; just then, in fact, stepping out of one of the most ornately gilded carriages, drawn by four splendid white horses with golden tassels in their manes and tails, she saw the young Grand Duke Dmitri, her father’s cousin, and his fast friend, Prince Felix Yussoupov, scion of the richest family in Russia.

Rumor had it that the Yussoupovs were even richer than the imperial family, something that Anastasia found impossible to believe. Who could possibly have more than the Tsar? The very thought struck her as rude, even if Felix himself was among the most charming and sought-after young men in all of St. Petersburg.

For well over an hour, the guests assembled in the grand ballroom until, at eight thirty sharp, the Master of Ceremonies banged an ebony staff three times on the marble floor and announced the presence of their imperial majesties. The mahogany doors, trimmed in gold, were thrown open, and Anastasia and her three sisters followed their father and mother into the immense ballroom, lighted by crystal chandeliers. All around them, men in medal-bedecked uniforms and black tailcoats bowed, while the women in billowing silk gowns curtsied with a fluttering sound that reminded Anastasia of flocks of geese taking flight above a field. Gems of every color and size sparkled at the ladies’ necks and ears and adorned their wrists and fingers. A prima ballerina from the St. Petersburg Ballet wore white shoes with heels and buckles made of pavé diamonds.

The orchestra broke into a polonaise, and while her parents went about greeting the guests – her mother wearing that telltale air of distraction that fell over her whenever her son Alexei was suffering from one of his agonizing bouts – Anastasia blushed fiercely and simply did her best not to trip over the hem of her long white dress. Because of the deformity to her left foot, her shoes were specially made for her by the court cobbler in Moscow, but the polished parquet floor was extremely difficult to navigate, and she dreaded taking a spill with every aristocrat in the land on hand to watch. The Grand Marshal of the Court, Count Paul Benckendorff, took her by the arm and proffered a glass of champagne.

Anastasia quickly looked around and said, “What if Mama were to see?”

“What if she does?” the count said with a laugh. The ends of his gray moustache stuck out from his face as straight as a pencil. “It’s New Year’s Eve, and you’re fifteen!”

When she still hesitated, he said, “Drink up!” and, laughing along with him now, she did. (In all honesty, she had sipped champagne several times before, but she knew that her mother still did not approve.) “And reserve the chaconne for me,” he added with a wink before moving off to welcome a party from the British Embassy.

While her older sisters danced, Anastasia looked on, making mental notes of everything she saw, the better to tell her brother Alexei the next morning. The Heir Apparent was sequestered in the royal family’s private apartments, recovering from a nosebleed that had begun with nothing more than a sneeze the day before. But because of his disease, the bleeding would not stop, and Dr. Botkin, in consultation with the best surgeons in St. Petersburg, was still debating whether or not to risk cauterizing the burst blood vessel that had caused it. Every doctor, Anastasia knew well, dreaded being the one who might do the Tsarevitch greater, or grave, harm. As a result, they generally chose to do nothing but wait and watch and pray that each crisis would pass.

Rasputin had, of course, been summoned – indeed, he was due at the ball – but, as often occurred, no one had been able to find him yet. Famous as he was, he also led a secretive private life. Anastasia had heard tales about that, too – some of them quite scandalous – but her mother adamantly insisted that the stories were all a pack of lies, made up by political and personal enemies of the man she called, with reverence and affection, Father Grigori.

By now, there must have been close to a thousand people in the ballroom, and scores of servants were circulating on the perimeter of the dance floor with silver trays of caviar and sliced sturgeon, flutes of champagne and glasses of claret. Massive buffet tables, laden with everything from lobster salad to whipped cream and pastry tarts, were set up in the adjoining chambers. But Anastasia was so enraptured by the beauty of the ball that she longed to sweep around the room to the strains of the mazurka or the waltz. She only trusted herself, however, in the arms of a few, among them the count. When he returned for the chaconne, and wrapped a strong arm around her waist, she knew that he would support her and guide her steps; as they danced she was able to tilt her head back and feel herself briefly transported. The champagne, she thought, was a great help; she should drink it more often. She saw her sisters – Olga and Tatiana and Marie – moving around her, and to her they looked as graceful as swans. Was she forever to feel like the ugly duckling, she wondered – which made it all the more surprising when she saw a hand in a white-leather glove descend upon the count’s shoulder and heard a voice say, “May I intrude?”

The count put his head back, and said, “But I was just hitting my stride, Prince!”

Yussoupov smiled and as the count relinquished his hold, boldly stepped in. Anastasia could hardly believe what was happening. Prince Felix Yussoupov could dance with anyone he liked, anytime he liked. He had dark, wavy hair, and a long, almost feminine face, with dark, soulful eyes. His lashes were longer than any of her own sisters’, and as she looked at them now, closer than she had ever seen them before, she could swear that they had been tinted and curled, and she remembered the gossip she had overheard – that the young prince liked to be seen around town masquerading as a woman, in furs and jewels and silken gowns. She had never known what to make of such tales, especially as he had recently married a celebrated beauty named Irina – who was nowhere in sight at the ball.

As if intuiting her thought, he said, “The Princess Irina’s in the Crimea, at Kokoz.”

No matter how splendid the Yussoupovs’ palace there was – and the accounts of its magnificence were many – Anastasia could not imagine missing the Tsar’s Christmas Ball.

“But I see another guest is missing, too,” he said, as she sailed in his arms across the dance floor. The prince was an even more adept dancer than the count.

“Alexei is asleep,” she said. “He was out hunting all day.” Like the others in the royal family, she had been tutored to conceal the gravity of her brother’s condition.

The prince nodded and smiled, but she understood now that it wasn’t her brother he had been referring to.

“Oh, do you mean Father Grigori?” she said.

For some reason, Yussoupov seemed to find that funny, and laughed. Even his teeth were perfect – small and even and brilliantly white.

“Yes, of course, Father Grigori,” he said, and now she knew he was making fun of her for calling him that. “Our friend Rasputin must be on quite a bender if he’s late to the Winter Palace ball.”

Anastasia was perplexed.

“He’s coming tonight, isn’t he?”

“I should think so,” she replied. But did he think that she oversaw the guest list?

“I ask because you two seem to have a special rapport, n’est-ce pas? Whenever we go out drinking together, the good Father Grigori speaks of your family often – but he talks about you more often than all the others combined.”

That he spoke of them at all was shocking to Anastasia, but she couldn’t help but wonder what it was he said about her. She was secretly flattered. Without her having to ask, Yussoupov obliged.

“He seems to think that you carry what he calls a ‘spark of holy fire.’ And if anyone should know about such stuff as that, it’s Rasputin.”

Anastasia was growing dizzy, though she couldn’t tell if it was from the twirling of the dance, the champagne, or the confusion she felt at the strange turns of the conversation. What did Felix Yussoupov want from her?

“Does he ever speak of me?” he asked.

“Not that I can think of. Why would he?”

“We are the best of friends,” he said, with feigned indignation, “that’s why. But he can have a wicked tongue on him, and I’ve just been curious to know if my name ever came up behind the closed doors of the imperial apartments.” His eyes, deep and dark and penetrating, were staring into hers, and she felt as if a wolf were sizing her up for dinner.

“I think I need to sit down,” she said, suddenly feeling unsteady on her feet.

The prince, without missing a beat, swept her from the floor and onto a gilded divan framed between a pair of floor-length mirrors. Two other ladies quickly moved to make room for their royal addition.

“Forgive me,” the prince said, bowing at the waist with one hand folded behind his back. “I fear my conversation has proved tiresome to Your Royal Highness.” Anastasia still had the sense that he was somehow mocking her. Mocking a grand duchess! “I’m sure our mutual friend will turn up any minute. Wherever the champagne is flowing, Father Grigori cannot be far behind.”

As he retired, the other ladies fluttered their eyes and tried to catch his attention, but to no avail. He was already hailing Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and gesturing toward one of the buffet chambers. And so the ladies set their sights on Anastasia, instead.

“You look very lovely tonight, Your Highness,” one of them gushed, and the other said, “But where has your mother gone to? Her dress was quite beautiful and I was eager to study it more closely.” She leaned closer with a smile and said, “That way I can get a better copy made when I leave for Paris.”

Flattery was something Anastasia, like any member of the royal family, was inured to. Her mother and father had brought her up, as best they could, to ignore it. For an honest opinion, there were family members one could turn to, and certain confidantes and retainers, such as Dr. Botkin, the French tutor Pierre Gilliard, or Anna Demidova, her mother’s maid who had served the Tsaritsa forever and whose loyalty and love were undoubted. And even though Jemmy was just a cocker spaniel, Anastasia knew that the little dog would love her just the same whether she was a grand duchess or a peasant girl. She wished that people could be more like dogs.

A servant offered her another glass of champagne, and with her mother nowhere in sight, she saw no reason not to take it. She was done dancing for the night – her left foot already ached a bit – and she chatted amiably with the two ladies, both of whom turned out to be the wives of ministers of something or other (ministers came and went so routinely that Anastasia never bothered to get their names straight) and began to wonder at her mother’s absence. The Tsar himself was holding court at one end of the ballroom, but it was beginning to dawn on Anastasia that if her mother had already disappeared – and Father Grigori had not shown up at all – there could only be one reason.

Alexei must have taken a turn for the worse.

Excusing herself, she skirted the dance floor, waved good night to Count Benckendorff, and lifting her long skirt a few inches, scurried down one of the vast galleries lined with towering columns of jasper, marble, and malachite. Some late-arriving guests swiftly stopped to bow and curtsy as she passed, then she was hurrying up the main staircase and down several more corridors, decorated with rich tapestries and gloomy oil portraits, until she reached the family’s private quarters in the East Wing. Comprised of only twenty or thirty rooms, most of them overlooking an enclosed park, this was the Romanovs’ sanctuary, the place where they could live a relatively normal, uninhibited, and unobserved life. The Ethiopian guards silently opened the doors as she approached, and just as silently closed them behind her a moment later.

She was running toward her brother’s rooms when she happened to notice that the door to her mother’s private chapel was ajar. Candlelight flickered from within, and when she peered around the open door, she saw Rasputin standing before the altar, surrounded by votive candles and dozens of holy icons – portraits of the Virgin Mary, or various saints, daubed in gold and silver, on resin wood or bronze. He did not hear her as she entered, so absorbed was he in his prayers, and though she did not wish to startle him, she needed to know if her brother was in danger.

“Father Grigori,” she murmured, and as if he had known she was there all along, he said, without turning, “I have comforted the Tsarevitch, and he will live.”

She waited, relieved – what kind of Christmas would this have been if he had not? – and wondering if she should leave the staretsto his prayers.

“But my own time is fast approaching,” he said, the candlelight glinting off the pectoral cross.

He turned his head without turning his body, and despite her reverence for the holy man, Anastasia was reminded of a snake sinuously twisting its neck around. His eyes were smoldering in their sockets.

“I shall not live to see the New Year,” he said. “I have written it all down in a letter I have given to Simanovich.”

Simanovich, Anastasia knew, was his personal secretary, a slovenly man who reeked of tobacco juice and sweat.

“But it is for your father to read one day. If I am killed by common assassins, by my brothers the peasants, then you and your family have nothing to fear; the Romanovs shall rule for hundreds of years.” Then he raised a finger in warning, his beard bristling as if with electricity. “But if I am murdered by the boyars – if it is the nobles who take my life – then their hands will be soiled with my blood for twenty-five years. Brothers will kill brothers. If any relation to your family brings about my death, then woe to the dynasty. The Russian people will rise against you with murder in their hearts.”

The blood froze in Anastasia’s veins. She had never heard him speak in such apocalyptic tones, and for the first time she drew back from him in fear.

“That is why you must take this,” he said, grasping the emerald cross on its chain. “You must wear it always.”

He lifted the cross over his head, then draped it over hers, turning it so she could see the back. Their heads were so close she could smell the liquor on his breath and see the dead-white skin beneath the zigzag part in his long black hair. “It was to be my Christmas present to you. Look, my child, look.”

There was an inscription now, but in the flickering light of the votive candles, it was too hard to read.

“See? See what it says?” he implored. “ ‘To my little one.’ ” Malenkaya. “ ‘No one can break the chains of love that bind us.’ ”

It was signed, she could see now, “Your loving father, Grigori.”

“It is time you knew,” he said. “Although I will not be here in body, I shall always be watching over you in spirit. This cross shall be your shield.”

“But why me?” Anastasia said, her voice quavering to her own surprise, “and not the others?” She wished that her mother – or anyone, for that matter – would intrude on the private chapel and break this awful spell she felt being cast. “Why not my sisters? They’re older and”—she hesitated, ashamed, then blurted out what she was thinking—“more beautiful than I’ll ever be.”

Rasputin scoffed and reared back. “You are the one most beautiful in the sight of God,” he said, raising his own gaze toward the stained-glass ceiling.

“But what about Alexei? He’s the one who will rule Russia one day.”

“Hear me,” Rasputin said, before lowering his own voice and eyes. “The blood of your family is poisoned; the Tsarevitch is poisoned. It was matushkawho carried the taint.”

He often called the Tsar and Tsaritsa by the traditional endearments matushkaand batushka, terms that suggested they were the loving mother and father of their people. And though Anastasia had indeed learned about the curse of hemophilia being hereditary – she had heard her own mother one night wailing in her boudoir that it was she who had brought this suffering upon her son – she had never heard the monk utter anything so blunt and damning.

“This curse you carry in your veins will be your own salvation one day. A plague shall overwhelm the world, but you shall be proof against it.”

Anastasia thought he was babbling now, caught in the throes of some holy trance, and all she wanted was to break away. She deeply regretted ever leaving the ballroom.

“Thank you, Father, for the gift,” she mumbled, touching the cross – it was heavier than she might ever have imagined, and beautiful as it was, she wished that she did not have it. “I should go and look in on my brother now.” She drew back slowly, like a rabbit keeping a stoat in its view.

Rasputin’s gaze did not waver, nor did he move, as she edged toward the door. In his black cassock, framed by the dull glint of the holy icons in the candlelight, he looked like a pillar of smoke.

Not knowing what to say, she murmured, “The blessings of Christmas upon you, Father.”

“Pray for me,” he said.

And then, just as she put her good foot out behind her and stepped from the confines of the chapel, she heard him mutter, “For I am no longer among the living.”