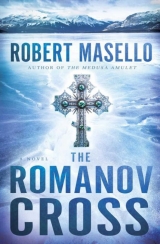

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Chapter 21

On the morning that Rasputin’s body was to be buried, Anastasia and the other members of the royal family bundled into two long black touring cars and drove from St. Petersburg to the imperial park at Tsarskoe Selo. There, a grave had been dug near the site where a church was later to be erected in his honor.

Anastasia had never seen her mother so bereaved. At the news of Father Grigori’s murder, she had utterly broken down, fearing that her son Alexei had lost his most potent protector. And when she learned that the deed had been done by Prince Yussoupov and, worse yet, Grand Duke Dmitri, a Romanov relation, she had almost lost her wits altogether. Anastasia and her three older sisters had taken turns watching over their mother.

Looking out the window now, Ana saw endless, snow-covered fields, lined by white birches and punctuated, like print on a white page, by scribbles of crows. It was a beautiful morning, with a sun so bright and a sky so blue Fabergé himself might have enameled the scene. Icicles hanging from the eaves of the occasional farmhouse glistened like diamonds. Under her own blouse, Ana wore the emerald cross the monk had given her at the Christmas ball. That was the last time she had seen him alive, and she had not taken off the cross ever since.

The body itself had not remained hidden for long. In their haste, the conspirators had left one of Rasputin’s boots lying out on the ice of the frozen Neva. The corpse had floated not far off, and when another hole was cut through the ice to retrieve it, the staretswas found to have been alive even after being submerged in the river. One of his arms had wriggled free of the ropes and was frozen stiff as if raised in a benediction, and his lungs were filled with water. For all the poison in his bloodstream, the bullets in his body, and the bruises from the beating, the monk had died in the end by drowning.

Once the cars had entered the park, and the Cossack guards had closed the gates and resumed their endless patrols again, Anastasia saw that wooden walkways had been built across a frozen field. The cars stopped, and Tsar Nicholas himself stepped out of the first one, his wife leaning heavily on the arm of her close friend, Madame Vyrubova. The Tsaritsa Alexandra was dressed entirely in black, as were they all, but carried in her arms a bouquet of white roses plucked that morning from the greenhouse at the Winter Palace.

In the distance, a motor van was parked by an open grave, its engine still running, a plume of gray smoke rising from its exhaust. As Anastasia drew closer, picking her way carefully over the freshly placed boards, she saw the foot of a coffin – a simple one, made of white oak – resting in the back of the van. Her mother went straight to it and asked one of the attendants to open it.

Looking uncertain, the attendant glanced at the Tsar, who nodded.

The lid was lifted, and though Ana was standing far back with her sisters, she caught a glimpse of the holy man’s black beard, stiffly brushed … and a ragged hole in his head, above his left eye, as if someone had drilled his skull with an augur. His broad hands, once so full of power and expression, were folded meekly against the shoulders of his black cassock.

All in all, it was the most shocking sight Ana had ever seen … but she did not quail, even as her sister Tatiana let out a whimper and Olga consoled her. In Ana’s head, all she could hear were the words Rasputin had spoken to her in the chapel.

“If any relation to your family takes my life, then woe to the dynasty. The Russian people will rise against you with murder in their hearts.”

And not only had Grand Duke Dmitri participated in the murder, he had bragged about it the next day.

“The blood of your family is poisoned,”the monk had said. “But this curse you carry in your veins will be your own salvation one day. A plague shall overwhelm the world, but you shall be proof against it.”

Ana still had no idea what these last words betokened. But she wore the emerald cross he had given her, with its secret inscription on the back, nonetheless.

Her mother handed the white roses to her friend and placed two objects on Rasputin’s breast. One was an icon that everyone in the imperial family had inscribed, and the other was a letter that she had dictated to Anastasia because her own hand was too unsteady. “My dear martyr,” it had read, “give me thy blessing that it may follow me always on the sad and dreary path I have yet to follow here below. And remember us from on high in your holy prayers.” Ana had held the letter for her mother to sign. Lifting herself from the divan, where the pain from her sciatica had once again relegated her, her mother had written “Alexandra” with her usual flourish, before pressing the page first to her heart, then to her lips.

Now, the letter, too, was lying on Father Grigori’s breast. The attendants closed and sealed the coffin, and it was lowered into the grave. A chaplain read the funeral service, but Ana was listening only to the sound of the winter wind as it rustled through the creaky scaffolding of the church being built close by. She looked at her family, standing silent and still in their black coats and boots and hats, all in a row, and it was as if she were looking at a photograph. A grim photograph that made her think of the monk’s dire prophecy again.

“Here,” Madame Vyrubova said, softly, “take this.” She handed Ana some of the white roses. And then, after her mother and father and sisters had cast their own into the open grave, Ana dropped hers, too, watching the petals flutter like snowflakes onto the lid of the coffin.

“I am no longer among the living,”Rasputin had said on that Christmas night.

But even now, even here, some part of Anastasia did not believe it.

Chapter 22

Lying in his sleeping bag on the floor of the cave, Harley checked the time on his cell phone. The phone reception was for shit – what would you expect from a cave on an island in the middle of nowhere? – but the clock told him it was 8 A.M.

And that meant it was high time to get this damn show on the road.

After they’d run the Kodiakaground the night before, Harley and his two next-to-useless assistants had off-loaded their supplies onto the skiff and laboriously toted them up the side of the sloping cliff and into the first cave that looked relatively safe and dry. They had left an LED light burning atop a crate all night, and looking around now, Harley saw the ration boxes and knapsacks stacked against the craggy stone walls, along with the shovels, spades, and, leave it to Russell, three cases of beer. Judging from the sound of his snoring, Russell was still sleeping off the cold ones he’d already drunk. Harley crawled out of his sleeping bag, kicked Eddie to wake him up, then, bending to keep from banging his head on the low ceiling, went to the mouth of the cave; they’d stretched a tarp between two crates to keep out the wind. Batting the tarp aside, he looked out on the cold, dark morning and the seawater frothing in the tide pools at the foot of the cliff. The boat was still marooned on the rocks, advertising their presence on the island, but at least it was stranded as far from the old Russian colony as it could get. Harley would have liked to find a hideout farther from the boat, just in case the Coast Guard ever came along and spotted it, but he knew that if he’d asked Eddie and Russell to hump the supplies any deeper into the woods, he’d have had a mutiny on his hands.

“What the hell time is it?” Eddie said, burrowing deeper into his bag to escape the cold blast from the entrance.

“Time to get up and get going.”

“Take Russell.”

But Harley had already decided to let Russell sleep it off. After the brawl that had erupted on the boat, he was wary of having the two of them along – especially on this first reconnaissance mission. He didn’t know exactly what was out there, and a loose cannon like Russell could wind up proving a liability. Plus, he wanted to cover some serious ground.

After they’d both eaten some canned Army surplus meals that Harley had picked up at the Arctic Circle Gun Shoppe, they stepped out onto the rocky ledge. Harley had strapped a twelve-gauge shotgun on his back and wedged a can of bear mace – made from concentrated red chili peppers – in his pocket. Over one shoulder he carried a spade; Eddie had a pickaxe. As they marched off, he had an unfortunate image of the seven dwarfs heading off into the woods.

Fifty feet in, and it started to feel even more like that damn fairy tale. The island itself was small, but forbidding. Densely forested with spruce and hemlock and alder, the ground was rocky and uneven and lightly dusted with snow, with a lot more to come if the weather reports were true. The prickly spines of devil’s club bushes snatched at their sleeves, and one of them even pulled Eddie’s stocking cap off his head. He had to stop and snatch it back, then, out of sheer annoyance, he broke the twig off and stomped on it.

“You sure it’s dead?” Harley said.

“Fuck you,” Eddie replied. “You have any idea where you’re going, by the way, or are we just out for a hike?”

It wasn’t a bad question. Harley had only the vaguest sense of where the colony lay ahead, and he figured the graveyard had to be part of it. “If we keep to a fairly straight course, we’re bound to hit it,” Harley said, turning around and cutting through some brush. He purposely made plenty of noise as he went since bears were partial to thickets like these, and a startled grizzly was a pissed grizzly. At this time of year, it was unlikely he’d stumble across any of them foraging for food – normally they’d be hibernating in their dens, or, if they were really lucky, the hollow core of a big old cottonwood tree – but it was better to be noisy than sorry, he figured.

Wolves, however, were another matter. Wolves were always on the move, year-round, scavenging dead carcasses, and hunting fresh prey – young caribou or unwary moose. Only on rare occasions had they been known to hunt man, and the one thing Harley had been taught was that you never ran from them. If confronted, you stood your ground, shouted, threw rocks, anything. Running was an invitation to be chased by the whole pack, though who knew how the black ones that inhabited this island – known to be a peculiar lot – would behave. There were all kinds of tales about them. Sailors told stories about seeing them lined up on the cliffs at night, looking across the strait toward Siberia, their muzzles raised, howling in unison. And a couple of hunters from Saskatchewan who had set out to bag a few never showed up again. Their kayak washed up a few weeks later, holding a bloodstained pair of gloves and a wooden paddle that looked like it had been nearly gnawed in half.

At the time, even though the two hunters were presumed dead, there had been some talk of mounting a rescue mission. But nobody had wanted to volunteer, and Nika, the newly elected mayor, had seemed perfectly okay to let things stand. It was almost like she was on the side of the damn wolves.

For another hour or so, they plowed through the forest, the evergreens towering high overhead, and just as Harley was beginning to fear he’d gone off course, he spied a clearing through the trees – and just beyond it, the timbered wall of a stockade. A wall that had fallen into considerable disrepair, its logs listing to one side or the other like misaligned teeth. To Harley’s relief, there was even a ragged gap large enough to offer easy entry to the colony grounds.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” Eddie said, coming as close to a compliment as Harley was ever likely to get.

And given the ghoulish nature of the work they were planning, Harley wondered for a moment if it wasn’t true.

“Is that their church?” Eddie said, and Harley, too, lifted his eyes to the crumbling onion dome that rose on the other side of the wall.

“Guess so,” he said. “And just as long as they’re not holding any services, it’s fine with me.”

The truth was – and despite the jokes – the whole place was still giving Harley a very uneasy feeling, not that he would ever confess anything like that to Eddie. For years, he had heard stories about the old Russian colony, and that was all before he’d been washed up on the beach that night and nearly lost his left foot to that leaping wolf … or glimpsed a flash of that yellow lantern sailors used to talk about spotting. But he had never imagined himself standing in the dark, frigid morning air, with a spade in his hand, about to enter the abandoned colony itself.

“Come on, man,” Eddie said, shouldering past him with his pickaxe cradled like a musket against his shoulder. “Let’s get this over with.”

Harley let Eddie slither through the opening in the wall first, then followed. They were at the back of the church, its wooden walls stripped bare of almost all their white paint by the years of wind and rain and snow. Angling around one side, he came across a window with only a splinter or two of glass jutting up from its frame; a lone shutter banged back and forth. As the church was raised on rotted pilings, and tilting a bit at that, Harley had to stand on his tiptoes to peer inside. Taking out the flashlight, he played its beam around the front of the nave and saw a faded mural painted on the opposite wall. From what he could see in the gloom, it had once been a picture of the Virgin Mary with a halo over her head. But what thrilled him was the touch or two of gold paint that was still left on the picture; those old Russkies loved their gold almost as much as they loved their Madonna. He hoped they’d buried some of that, too.

“What do you see?” Eddie said. “Let’s go inside and check it out.”

But Harley didn’t want to get sidetracked, especially as all he could make out besides the painted icon was a great big pile of junk – old milking pails, blacksmith tools, broken furniture – piled up against a carved screen. It looked like the place had been pretty thoroughly scavenged, and trashed, by somebody in the past hundred years.

“On the way back,” he said, just to shut him up. “Let’s find the cemetery first.”

As they passed the front steps of the church, with one door sagging and ajar, Eddie cast a longing look back but followed Harley past an old well and into the open area of the colony. They were surrounded on all sides by crumbling old cabins and open stalls. In one of them, Harley saw a rusted anvil, in another a pair of iron-hooped kegs. Plainly, it had once been a working village, with maybe forty or fifty people living in it. But all that concerned Harley was where these people went when they died. There was no sign of a graveyard anywhere, not even on the other side of the church. Weren’t folks supposed to be buried in the churchyard in the old days?

At the far end of the stockade he saw what had to have been the main gate to the colony – some weathered beams, off-balance like the totem pole in town, still framed the entrance – and after switching the shovel to his other shoulder, Harley set off for it. Outside, a path led away from the colony, across some cleared land, and straight into a dense grove of trees.

“Not another fucking forest,” Eddie complained.

“This one’s got a trail,” Harley said, striding ahead, and it did. Although it was narrow and winding, the path seemed to be leading him back toward the rim of the island. Gradually, it descended, and to Harley’s relief yet again, he saw a gateway ahead, like the colony gates only much smaller. And the posts, he noted as he got closer, were elaborately carved with something in Russian. It looked like the same word or two, chiseled into the wood over and over and over again. Even Eddie paused to study the writing. “You think it says, ‘Welcome to the buried treasure’?” he said.

And Harley could only wonder. Just beyond the posts lay the colony graveyard, no more than an acre, but littered with stone markers and wooden crosses tilting this way and that in the frozen ground. It was starting to get lighter out, the sun fighting its way through a scrim of hazy clouds, and in the faint daylight Harley could also see that many of the headstones had their own curious inscription down toward their base. It looked like a little crescent, but he was damned if he knew what that meant either. Did headstone makers sign their work? Shit, he thought, dropping the end of his spade between his feet, where was he supposed to start?

Eddie was wandering around among the graves, taking an occasional swipe at one of the wooden crosses with the end of his pickaxe, and Harley – who was by no means a religious man – still thought it was wrong and shouted, “Stop it, you dumb fuck.”

The gravity of what they were about to do struck him now like never before, and he cursed his brother Charlie, and he cursed himself for always playing the fool. How the hell did he get here?

Eddie stopped to take a piss, the urine splashing on the unyielding ground, and when he finished up and turned around, he said, “So, where do you want to start? I’m freezing my ass off already.”

And all Harley could think of was starting where it had all begun. With mechanical footsteps, he walked toward the rim of the graveyard, a precipice overlooking the Bering Strait. A coffin had fallen into the sea, and in only a minute or two he had found the spot from which it must have fallen.

At the very edge of the cliff, a hunk of dirt and rock had eroded away, leaving a scar in the earth. Harley took care not to step too close.

“That where you think it came from?” Eddie said, with a snort.

And Harley said, “Yes.” He stared at the jagged earth, and it was as if he was looking at a vanished grave … and worse. He could picture the gaunt man in the sealskin coat as he lay in the coffin aboard the Neptune II. Or as he appeared in the storage shed behind the gun shop.

Looking for his emerald cross.

“I say we pick the one with the biggest headstone,” Eddie said, surveying the graveyard. “The richer the dead guy was, the better the chances he got buried with some good stuff on him.”

With no better plan in mind, Harley had to concede it wasn’t the worst logic.

Eddie walked off a few yards, stopping beside a truncated stone angel, and said, “This one’s good as any.” And then, slipping the backpack off and tossing it to one side, he lifted the pickaxe and swung it over his head.

The iron barely grazed the soil before rebounding hard, and Eddie dropped the shaft and danced backward, swearing and shaking his hands.

Harley laughed, and Eddie said, “You try it then.”

“Let’s do this right,” Harley said, taking off his own pack, loaded with the steel climbing spikes and chisel. “If we loosen the soil first, we may get something done before dark.”

For the next hour or two, they bent their heads over the grave, alternately driving spikes into the ground, chopping at the surrounding dirt, scraping it away with the end of the spade. It was slow and backbreaking work, and Harley felt the futility of it with every breath. They should have brought dynamite and simply blown the place to pieces before that Slater guy showed up. His only hope lay in the fact that the Russian gravediggers must have had the same problems he was having; the graves they dug must have been as shallow as they could make them.

After taking a break to open some more tins of food – Eddie got Spam, and he made Harley trade it to him for his own can of corned beef hash – they got back to work. Eddie took a turn chopping and mincing at the dirt with the end of the spade, and when he caught what looked like the dull patina of buried wood, he got down on his knees and brushed the soil away with the ends of his sweaty gloves.

“That’s a coffin,” he exulted. “We did it, man!”

Harley told him to step back, then, lifting the pickaxe, he brought it down with a crash. There was the sharp crack of the blade cutting into wood.

Eddie was pumping his arms in anticipation of the treasure chest he thought they were about to uncover.

Harley wanted to tell him to cool it, but his own blood was up, too. If something did turn up in the casket, he’d have something to throw in Charlie’s face. Who’s the fuckup now?

He raised the pickaxe again, its dull iron blade framed against a sky of the same color, and even as he ripped it down into the coffin, something on the far horizon caught his eye.

The pick, as a result, missed its mark, and landed with a bone-aching thud in the frozen soil to one side.

“Watch what you’re doing,” Eddie said. “You gotta hit the spot that’s clear already.”

But Harley was watching that speck on the horizon again. It was just a black dot, but it was coming in their direction.

Eddie was using the spade to make a greater target on the top of the coffin. And when Harley didn’t lift the pick for the next blow, he said, “You want me to do it?” He reached for the pick. “Give it to me, ya pussy.”

Harley let him, not taking his eyes off the approaching speck. Which was now distinctly coming into view – it was a helicopter, undoubtedly the one from the hockey rink in Port Orlov – and it was coming right at them.

“Duck!” Harley said, and Eddie looked at him in confusion.

“From what?”

“From that!” he said, pointing at the oncoming chopper.

Now they could hear the racket of its engines and its rotating blades on the ocean wind.

Harley flattened himself against a wooden cross and Eddie huddled at the foot of the broken angel, his arms folded over his head. Unless the chopper stopped to hover above the cemetery, it would pass over them so fast they wouldn’t be seen … though their spade and pickaxe lay in plain sight on the snow. Damn. Harley reached out one arm and grabbed the spade and dragged it under him.

There was a rush of wind and noise as the chopper swooped low overhead, zooming straight over the graveyard and the trees and aiming for the colony grounds. Once it was safely past, Harley leapt to his feet and watched as it did indeed slow down and make a circular pass over the spot where the stockade walls enclosed the old settlement. Red and white running lights adorned its fuselage, blinking on and off, as the chopper, built like some huge green praying mantis, seemed to suspend itself in midair, before descending below the tree line, and out of Harley’s view.

“Fuck me, man,” Eddie said. “They’re here already?”

He was right about that, Harley thought. They were well and truly fucked if these guys were here for anything more than a quick stopover, or, as those douche-bag pilots had claimed, a “routine training mission.”

His eyes went back to the splintered coffin in the partially exposed grave. And so did Eddie’s.

“No way I’m letting those assholes get what we dug up,” Eddie said, rising from the foot of the tombstone.

And neither was Harley, though he knew there wasn’t much time. Brushing the dirt and ice from his gloves, he raised the pick and taking a deep breath first, swung it high above his head, then brought it down one more time with a satisfying thwack.