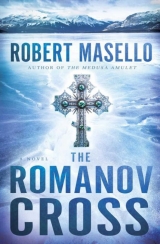

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Chapter 55

“Is that it?” Slater asked. “Is that the van?”

Nika craned forward in the passenger seat. “I can’t tell,” she said, peering through the fractured windshield. “The snow’s too thick.”

On the right side of the road, a yellow sign said, “HERON RIVER BRIDGE AHEAD. PROCEED WITH CAUTION. REDUCE SPEED.” It was pocked with bullet holes, and Slater wondered if there was a single sign or mailbox in Alaska that hadn’t been used for target practice.

He stepped on the gas, but he felt the tires starting to lose traction on the icy surface and he had to ease off again.

The road was winding its way through a rubble-strewn landscape of stunted trees and immense boulders. Sometimes, the vehicle in front of him would disappear behind the rocks, or be engulfed in a whirling cloud of snow, but each time he caught a glimpse of it, he was able to pick out another detail or two. First, he could see the boxy silhouette of a van. And then he could tell it was some dark color, blue or black.

It had to be Charlie Vane’s car.

He knew that he was driving the ambulance far too fast for the road and weather conditions, but he still wasn’t closing the distance. Vane had to be doing at least sixty-five or seventy miles per hour. At any moment, he expected to see the van go spinning off the road or crashing into the rocks.

“Do you think they’ve spotted us?” Nika asked.

“Absolutely.” But what would they be able to see? “Should I put on the siren and lights? Maybe convince them it’s the police on their tail?”

“They’d only drive faster.”

Which was pretty much what Slater had thought, too.

“There’s one more bend in the road,” Nika advised him, “but it’s a wide one, and it runs behind those hills. When you come out on the other side, you’ll see the gorge, and the bridge, off in the distance but straight ahead.”

What Slater hoped to see was a National Guard barricade, with spotlights and trucks and armed soldiers, but he was afraid it was too much to expect. There probably hadn’t been time to set up something so elaborate, and now he was wondering just how far he would have to keep trailing the Vanes. All the way to Nome? He glanced at his dashboard and saw that the gas tank was already three-quarters empty. But it was critical that he stop them before they reached any population center.

The question remained – how?

Snowy hills rose up on all sides, funneling the wind and snow into a dense fog that almost entirely obscured the road. Steel poles, only four or five feet high, with red reflectors on top, were the only way to stay on course, and rusty signs warned of curves, oncoming traffic, animal crossings, avalanches, hazardous ice. The ambulance clung to the road, the windshield wipers beating furiously, the lone headlight shining on the blur of falling snow. A steady stream of freezing air blew into the car through the hole in the windshield, and Slater prayed that the wipers wouldn’t catch on one of the cracks and cause the whole window to implode in their faces.

And just when he thought the hills would never come to an end, he emerged onto a broad icy plateau. Even the van must have had to slow down, as the distance between them now was no more than the equivalent of a few city blocks.

Better yet, Slater could see the steel span of the Heron River Bridge, rising into the darkness … with an Alaska Highway Patrol car parked laterally in front of it, its headlights shining and blue roof bar flashing.

It wasn’t a whole platoon from the National Guard, but it would do.

Or so he thought.

He watched the van begin to slow down, as if Charlie was debating what to do, and Slater used that chance to close some more of the gap.

“Okay, now let’s turn on the lights and siren!” Slater said, clutching the wheel with both hands as he suddenly felt the ambulance sliding on a patch of black ice. “Time to let him know he’s surrounded.”

But just as Nika got everything blaring, and Slater saw the patrolman stepping out of the car, the van shot forward, its back wheels hurling up a shower of snow and sleet as it rocketed toward the bridge.

“What’s he doing?” Nika shouted.

But it was clear seconds later, as the van accelerated to top speed and hit the front end of the patrol car, sending it spinning out of the way like a top, sparks flying and metal screeching. The cop jumped out of its path in the nick of time.

Slater, trying to keep control of his own car, tapped his foot on the brakes and steered into the direction of the skid. But the ambulance had gathered its own momentum now.

Up ahead, the van bounded up the corrugated ramp and onto the bridge, bucking like a bronco trying to throw its rider.

In the ambulance, Slater clung to the steering wheel and Nika braced herself against the dashboard as the vehicle did a full, unimpeded circle before finally coming to a stop, its front fender thumping into a mound of snow.

After the initial jolt, Slater looked out his side window again, just in time to see the patrolman kneeling, one arm bracing the other, and firing several rounds at the back of the fleeing vehicle.

At first, the shots appeared to have no effect, but then, after the last one, Slater saw the van suddenly zig and zag on the bridge, cutting from one lane to the other, before banging into a guardrail so hard that two wheels left the pavement, then all four. As it flipped over, tires smoking and glass spraying, it spun, like an upside-down plate, halfway down the deserted bridge.

“You okay?” Slater said to Nika.

“Yep,” she said, in a shaky voice, “but I’m not so sure about the ambulance, or the Vanes.” She, too, was looking off at the wreckage on the bridge.

He told her to use the radio to call for medical backup. “And stay on the radio until they get here. Keep away from the accident scene.”

Then he leapt out of the ambulance, and raced toward the bridge.

“Who are you?” the patrolman hollered, still holding the gun. Slater was relieved to see that the patrolman, too, had a face mask – the word had gone out – but it was dangling down around his neck.

“Stay clear!” Slater shouted, running past the damaged patrol car. “And put your mask on until I tell you otherwise!”

“On whose authority?”

“Mine!” Slater declared. “And that’s an order!”

Before the cop could issue another challenge, Slater ran right past him, his eyes fixed on the van … and praying that this was as far as both of the Vanes, and the virus, had traveled.

Chapter 56

It was the chimes Charlie noticed first.

He was upside down in the van, his head up against the broken roof light.

The chimes, the ones that went off whenever you hadn’t fastened a seat belt, or closed your door properly, were dinging sweetly.

It took him a few seconds to orient himself.

He remembered slowing down for the roadblock, and he also remembered thinking, What was the point of trying to get past it? They’d have a chopper tracking him down next. And then, before he knew what was happening, Harley had flipped out in the backseat and started screaming, “Go through it! Go through it!”

But Charlie wasn’t going to be that stupid anymore; he’d seen enough trouble in his life, and he was a reformed man now, anyway. He was trying to reason with Harley when his brother, with the blanket still wrapped around his shoulders, lunged over the back of the seat and punched the accelerator lever.

“Go through!”

The van blasted off and Charlie, knocked back as if he were an astronaut, groped in vain for the hand brake as they smashed into the front of the police car, then, instantly picking up speed again, hurtled past.

His fingers were just able to graze the wheel as the van lurched onto the bridge, but Harley was hanging over him, trying to steer. He thought he’d heard a shot – or was it a tire exploding? – and then they were crashing into a metal guardrail, the windows shattering all around. Gas canisters and gear from the back of the van flew in every direction as the wheels hit an ice slick, and the whole car flipped in the air like a pancake on the griddle.

And now all he could hear were the chimes. The inside of the van smelled like gasoline, tinged with the astringent smell of blood. His neck and shoulders aching, he glanced at the front of his coat, where a wet, dark stain was slowly spreading. The punctured airbag was hanging down like an empty saddlebag, and the glove compartment gaped open. Its contents, including the cross and icon, were scattered somewhere in the jumble of pulverized glass and twisted metal.

“Shit.”

He heard that. It was Harley’s voice. He was alive – but where?

Gradually, other sounds came to him, too. The dripping of gasoline, the creak of mangled steel, the tinkle of falling glass. The world was returning … and with it, agonizing pain.

Charlie tried to turn, but the seat belt was coiled like a snake around his waist, and his legs of course were as useless as ever. He tried moving, but only one arm came up from the wreckage. He tried to reach for the buckle on the seat belt, but the bulk of his coat was bunched up and in the way.

“Where are you?” he asked through gritted teeth.

He heard a moan, and something twitched behind his head. He had the impression it was a foot. “Try not to move,” he said, mindful of his own paralysis. “They’ll get a medic out here.” But how long would that take? They were in the middle of nowhere, in a snowstorm.

“I told you,” Harley groaned. “I told you I was gonna die tonight.”

Charlie had to admit he hadn’t been far off. But the good Lord still seemed to have some other plan in mind for them.

And then, under the howling of the wind, there was the sound of running feet. And a guy in some kind of white lab suit was crouching down beside the wreck. He had a gauze mask on, and rubber gloves. How could medics have gotten there this fast, he wondered?

Peering in at Charlie, he quickly assessed the situation, and said, “Can you breathe?”

“Barely,” Charlie replied. “The seat belt.”

And then the guy’s hands were working the buckle, prying it loose. When it popped open, Charlie’s belly fell and he felt a rush of cold air entering his lungs. Then his coat was being opened, and the medic took a long look without saying anything. Two of the spokes from the gearshift were sticking out of him like bent twigs.

“Hang in there,” he said evenly, “you’re gonna be okay.”

Christ, that’s exactly what they’d said to him after he’d hit those rocks running the Heron River Gorge.

Then he closed the coat again, and moved beyond Charlie’s narrow field of vision, to tend to Harley in back.

“Can you move your head and neck?”

Harley groaned again and swore, but the medic was slowly extricating him from the wreckage. “Don’t move anything you don’t have to,” the medic said. “Just let me do it.”

Through the empty space where his window had been, Charlie could see his brother’s mangled body being pulled from the van and onto the asphalt. Heavy snow was falling, mixing with a widening pool of something wet and viscous. For a second, Charlie thought, Could that be blood?But then he realized it wasn’t. It was gas.

Harley’s groaning was becoming more of a scream. And he was shouting something about Eddie again. “Goddamn it, Eddie, it wasn’t my fault!”

And he was struggling with the medic. It seemed like he thought the guy wasEddie.

“Calm down,” Charlie mumbled to his brother. Funny how his guts were growing colder by the second. “He’s not Eddie.”

“Fuck you,” Harley spat at the medic, his arms flailing under the blanket drenched in blood. And then, in a flash, one of his hands broke free, and it was holding the goddamned Glock semiautomatic.

“I told you to quit it!” Harley shouted. “I toldyou!”

The medic grabbed for his wrist, but not before a sudden spray of shots went wild into the snowy night sky.

The medic twisted the wrist, banging it on the road and trying to free the gun, but Harley managed to pull the trigger one more time. Charlie saw a blazing arc of light, a bright and beautiful orange parabola that nearly blinded him, as the bullets ripped into the overturned van and punched holes in the gas cans. That was when the whole world lifted off, painlessly and effortlessly, with an all-enveloping whomp, and Charlie was carried up into the air, as if by the Rapture itself … up out of the wreckage, out of his own maimed body, and into a darkness so deep, so dense, and so comforting that he could actually feelit …

Chapter 57

Nika froze, the radio handset dropping into her lap, as she watched the fireball unfurl and the ruined van shoot up into the air. A moment later, the impact of the blast reached the ambulance, shattering the splintered windshield and raining glass down onto the dashboard.

The boom sounded like a distant thunderclap, and the chassis of the ambulance shimmied.

“What was that?” a static-y voice asked over the radio. “Are you still there?”

Pieces of the van started crashing down on the asphalt, while others flew in flames over the side of the bridge.

“Please reply,” the operator insisted. “Are you okay?”

Nika was lifting the mike when something slammed down on the hood of the ambulance, then ricocheted through the gaping hole and onto the seat beside her. She looked down at it – half a leg, in blue jeans, soaked in blood, the foot still attached. And then, in shock, she bolted out of the car.

She was running for the bridge, right past the patrolman who was standing outside his damaged car, mike in hand and the cord stretched to its limit. She heard him saying, “Emergency! Now!” She just kept telling herself, Frank wasn’t wearing blue jeans. He was wearing the white lab suit. He could still be all right.

When she got to the ramp of the bridge, she could see bits of burning wreckage still wafting to the bottom of the gorge. The wind reeked of gasoline and carnage. She ran on, toward the cloud of black smoke and destruction, but as she got closer she had to slow down and pick her way, while squinting her eyes against the acrid fumes, through the smoldering debris.

“Frank? Can you hear me? Frank?”

The storm was whipping the smoke and ashes into an evil, dusky brew. As she stopped for a second to clear the tears from her eyes, the cop ran past her, sweeping his flashlight back and forth. Its bright beam picked out hunks of torn metal and wood and fabric … and chunks of scorched body parts.

Please, God, she thought. Please, God, let me find him.

“Frank!” she called again, the dirty air searing her lungs as she plowed ahead. She remembered the face mask hanging around her neck, and quickly fixed it over her mouth and nose. She was never so glad to have it.

An axle of the van, with two wheels still connected, lay like a barbell in the middle of the roadway.

The side of her foot bumped against something that rolled, like a black bowling ball, down the white line of the bridge. It was only as it rotated that she saw it was a perfectly smooth, perfectly burned, perfectly unrecognizable head.

She stopped in her tracks, afraid to move another step or see another horror. Gusts of wind kept picking over things that had fallen back to earth, blowing them around as if for further inspection, but Nika couldn’t bear to look. She lowered her eyes, breathing hard, and saw something shining in the glow of a burning seat cushion. It was a cross, made of silver. With emeralds that sparkled in the light of the fires crackling all around them. What on earth would that be doing here?

“Over here!” the patrolman cried, holding the mask away from his lips.

He was crouched by the railing.

“Over here!”

Nika jumped over a twisted muffler pipe and went to the railing.

A body, nearly ripped in half, was lying with a shredded blanket wrapped around it. Already she could tell it was missing a couple of limbs.

Her heart plummeted like a rock, but then the patrolman, pointing his flashlight, said, “Underneath! Look underneath!”

She brushed the cinders out of her eyes.

And then she saw that someone else lay there, too, shielded by the mangled corpse.

“Help me,” the cop said, snapping his mask back into place and starting to disentangle the two.

They allowed what was left of the body on top to slither to one side. Enough of it remained, even now, that she could recognize Harley Vane.

And beneath him lay Frank, his lab suit soiled with blood and ash, the ivory owl on its leather string draped over one shoulder. When she said his name, she saw his eyelids flutter. His mask was gone, and his face was seared and bleeding. But she saw his lips move.

“Lie still,” she said, tenderly brushing soot from his cheek. “Don’t try to talk.”

But he tried to, anyway … and she could swear he said “Nika.”

Turning to the cop, she said, “Call for a medical evacuation. We need a helicopter as fast as they can get here!”

But he was shaking his head. “I radioed already, and every chopper is on duty enforcing the quarantine. It’ll be hours before any help gets here.”

Hours was not something Nika had to spare.

“Then I’ll need to take your patrol car.”

“Have you seen what’s left of it? You’ll be driving with no hood.”

Her brain was racing. Her only option was the ambulance with the missing windshield, the lone headlight, and not enough gas. “Can you drain your gas tank into the ambulance for me?”

“That I can do,” he said, plainly relieved that he could finally offer some sort of help, and headed back across the smoldering minefield.

Nika bent low over Frank, trying to assess his injuries, but he was so saturated in blood it was hard to tell. His face was covered with cuts and abrasions, and she carefully raked her fingers through his hair, stiff and matted, in search of any gash or obvious wound. To her relief, she found none. Loosening his hazard suit and trying to peer inside, she could see no open wounds or protruding bones, but internal injuries, even she knew, could be a lot less apparent and much more deadly.

When the patrolman returned with the gurney, they lifted Frank onto it, wheeled him to the back of the ambulance. On the way, Nika’s eye was caught again by the silver cross, glinting among the broken glass and metal, so she stuck it in her pocket. She assumed it was a family heirloom that Vane’s wife would want back, and it might make a small peace offering after all that had happened. Way too small … but still, something.

After they had secured the gurney, the patrolman said, “I still don’t know how you’re gonna make it, in this weather and this vehicle.”

But Nika was already hauling out the medics’ gear stashed in back. She slung on a huge red anorak, with white crosses on its sleeves and a voluminous hood. Her face was barely visible under the dirty mask, and even the remainder she covered with a pair of protective snow goggles. Her hands, still in the latex gloves, went into thermally insulated gloves. When she was done, the cop said, “You still in there, Doc?”

Somewhere along the way, maybe because of the white suit and ambulance, he had assumed she was a doctor – and she had been savvy enough not to correct him. She nodded in answer to his question, but even that movement might have been lost in the folds of the hood.

“I’ll radio ahead and let ’em know you’re coming.”

Then she brushed the broken glass away from the driver’s seat, removed the severed leg and deposited it on the roadway, and fastened her seat belt. The patrolman, using his flashlight like an airport worker directing a jet onto the right runway, helped guide the ambulance through the carnage and debris on the bridge – little piles were still burning like signal fires – and then waved her on her way. She lifted a hand in salute, and glancing in the rearview mirror, watched as he was swallowed up in the maelstrom of the storm.

Chapter 58

Once the plane was completely out of sight, even the sound of its motor lost in the rustling of the wind along the abandoned airstrip, Anastasia said, “There was a village, on the cliffs. I saw it before we landed.”

But Sergei stood where he was, his black sealskin coat billowing out around him, his eyes still fixed on the blue but empty sky.

“Sergei, he’s gone. There’s nothing we can do about it.”

He was still clutching a stone – he had thrown several in impotent fury at the plane – and looked reluctant to give it up.

Ana, deciding to give him time, went to the shed and looked inside. Plainly, it was a depot for the planes, with gas cans and tools and various pieces of machinery lying around, but nothing she could see that would be of any use to them.

“I’m sorry,” she heard over her shoulder. “I was a fool.”

“We both were,” she said, remembering that it was she who had encouraged him to hand over the second diamond. “Anyone who trusts another Russian,” she added bitterly, “is a fool.”

Taking his hand, she led him across the field, favoring her bad foot, which had accumulated many blisters on their journey, and back toward the cliffs where she had seen the dismal huts. Halfway there, she saw several figures approaching – three men, squat and broad, swathed in fur coats, with their hoods thrown back and something odd about their faces. It was only as they came closer that she saw the men had ivory disks, the size of coins, implanted in their jutting, lower lips. She knew that these must be the Eskimos; with their wide, weather-beaten features, high cheekbones and black eyes, they reminded her of the Mongolian trick riders who had once performed at Tsarskoe Selo for her parents’ anniversary.

Ana and Sergei stopped and let the men close the remaining distance. The two younger ones stood back, while the third, with woolly gray eyebrows and leaning on a staff, raised a bare hand and said, “Da?” Yes.

Ana did not know what to reply. The man was looking around, as if he, too, was puzzled at the lack of a plane, a pilot, or any explanation for their being there.

“Da?”he repeated, and she wasn’t sure he understood what he was saying himself.

“My name is Ana,” she said, “and this is Sergei.”

The old man nodded.

How, she wondered, should she continue? “I’m afraid that we may need your help.” Did he understand any other words of Russian?

“We want to go to St. Peter’s Island,” Sergei spoke up, pointing off to the east. “Saint. Peter’s. Island.”

“Kanut,” he said, lightly touching his fingers to the front of his coat.

Ana, smiling tightly, repeated their own names, and the old man nodded in agreement again. “Do you speak Russian?” she asked.

“Da.”Then added, “Some words.”

Thank God, she thought. It might be possible to make themselves understood, after all, but before she could begin, he had turned around and was heading back toward the cliffs. She could only assume that they were meant to follow, especially as his two henchmen waited for them to go on before bringing up the rear. Bewildered as she was, she did not feel threatened, as she would have with her own countrymen.

The village, if you could call it that, was not far off. She could hear huskies barking and smell smoke before she saw the huts again; there were no more than ten or fifteen of them, and they were the crudest structures she had ever seen, low piles of stone with skins stretched across the tops to make a roof. Steep trails led down the cliff to a sliver of rocky beach where canoes and kayaks were laid upside down across racks made of whalebone. Raised on its own poles was a wooden lifeboat with the name Carpathia, in Russian, still faintly legible on its side. Sergei squeezed her hand and with the other pointed off across the Bering Strait. In the distance, like a black fist rising from the sea, she could just make out a tiny island, oddly surrounded, even on a clear day like this, with a belt of fog.

The old man bent low and lifting a sealskin flap ducked into one of the hovels. Within, Ana was surprised to find the room so warm and spacious. The hard ground was covered with many layers of pelts and furs, haphazardly overlapping each other, and two women, as short and broad as the men, were tending to a primitive hearth with a tin chimney spout in the corner. Ana heard the bubbling of a samovar and smelled the surprising aroma of Indian tea. When one of the women, smiling with worn-down yellowed teeth, brought them the tea, it was in chipped china cups with gold rims and Carpathiawritten on them again. Ana had the strong sense that these things had all been salvaged from a wreck of the same name.

But it was clear to her that Kanut was doing his best to show them the royal treatment. And though no sugar or lemon or milk was on offer, not to mention the traditional tea cakes, beautifully decorated and arrayed, that she had once been so accustomed to, it was the most welcoming and delicious cup of tea she had ever been served. Much as her heart had hardened since Ekaterinburg, she was equally touched by any small display of human kindness.

“How did you learn to speak Russian?” she asked, carefully enunciating each word. Shrugging off his coat, the old man revealed an embroidered, deerskin vest fastened with whalebone buttons, and a little carved figure of a bear hanging down around his neck. She wondered if it was a bear that also adorned the plate in his lip.

“Traders,” he said. “I work on ships.” He held up an arm, hand clenched as if to hurl a harpoon. “Ten year.”

At her side, Sergei radiated impatience, and she put a calming hand on his arm. “Drink the tea,” she said gently, “it will refresh you,” before thanking their host directly. Despite the strange surroundings, she felt as if she were back in one of the imperial palaces, welcoming a delegation from one of the far-flung outposts of the empire. Her family had once ruled nearly a sixth of the globe, and now she was reduced to the clothes on her back and the treasures in her corset. How thankful she was, yet again, that she had had the foresight to wear it, rather than stuffing it in their stolen bundle.

For several minutes, they haltingly talked about his adventures at sea – he had apparently traveled through most of the Arctic regions, hunting beavers, walruses, seals, whales – but Ana could sense the pressure building in Sergei. He kept crossing and recrossing his legs, clearing his throat, even coughing. Finally, when he could stand it no more, he broke in to say, “Can we hire you, or some of your men, to take us across to the island? We will gladly pay you whatever you want.”

Although the old man smiled politely, Ana could tell he was offended at having his colloquy interrupted. He seldom had a new listener, she imagined. But when he shook his head, it was with more than petty annoyance.

“No. Not there,” he said.

“Why not?”

“Bad luck,” he said, his fingers unconsciously grazing the ivory bear around his neck.

Was it his good-luck charm, Ana wondered? His equivalent of the emerald cross beneath her blouse?

“Is it because the Russian settlers are there?” Sergei pressed on. “I can promise you, they will do you no harm. They are followers of a great man, a holy man, known as Father Grigori.”

But the old man was as stolid and impassive as a boulder.

“He was also called Rasputin,” Sergei said. “Surely you have heard of him by that name.”

“Place for spirits,” he said, of the island. “I tell them, do not go there. Place for the dead. Do not go.”

Ana had the impression that he was saying it was a holy place for the Eskimos, sacred ground that the colonists had defiled by their very presence. Even that one glimpse of it that she had had confirmed her suspicions. It was a forbidding spot.

But Sergei was not to be dissuaded. For that matter, neither was she. They could hardly return to Russia now, and they had come all this way to find a safe harbor, if only for a year or two, until the world had come to its senses and the Reds had been turned out of power as ruthlessly as they had taken it. No, she was as determined as Sergei to reach their destination, especially now that it was within sight.

“Well, then, if you don’t want to go,” Sergei said, “what about selling us one of those boats down on the beach? The one from the Carpathia?” He held up his cup and pointed at the word on his teacup.

Kanut frowned.

“How much do you want for it?” Sergei went on, glancing at Anastasia. Reaching inside her coat, she drew out the drawstring bag in which they kept their ready bribes, and Sergei opened it, rummaged around inside, and took out a sparkling yellow diamond. He held it out toward the old man. “It’s worth a thousand rubles. And what’s that wooden boat worth?”

When the old man showed no interest, Sergei took out a sapphire so big and so blue it looked like a blueberry. “Both of them, you can have them both.”

But Kanut still didn’t budge. Ana didn’t know if this was some bargaining tactic, or if he was sincerely uninterested.

Sergei’s frustration was growing, but then he seemed to have hit on something. He dug deeper into the pouch and came out with three gold rings that had once belonged to Ana’s sisters. Her heart ached at seeing them. But Sergei was right – the moment the gold appeared, Kanut paid attention. He didn’t care about gems, but gold was the currency of the world, particularly in these regions where so much of it was mined.

“The rings – pure gold – you can have all three.”

Kanut held out his palm, and when Sergei had dropped the rings onto it, he left it there … waiting for the diamond and the sapphire to join them. So, Ana thought, he wasn’t so impervious to their beauty, and their value, after all. Sergei reluctantly handed over the jewels, too. They had just bought a sailboat for the price of the imperial yacht Standart.

The old man pocketed the booty in his vest, and perhaps afraid that these two fools might regret the deal, stood up and said, “You must go soon. The tides.” He shouted some instructions to the women, one of whom was just about to serve them some hunks of cured blubber, and motioned for Ana and Sergei to follow him.

Outside, the two men who had been accompanying Kanut were crouching on the tundra, tossing fishtails to the dogs, who were straining at their chains. The old man issued some order in their native tongue, and the men looked puzzled. The old man said something more, and Ana saw one of them, with a gold tooth in the front of his mouth, look at her and laugh. She did not need a translator to grasp the gist of what had been said.