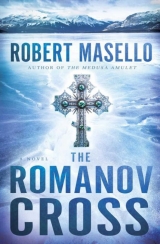

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Robert Masello

The Romanov Cross

Prologue

THE BERING STRAIT, 1918

“Sergei, do not die,” the girl said, turning around in the open boat. “I forbid you to die.” She had hoped, in vain, that her voice would not falter.

When she tried to reach out to him, he pulled away, still holding on to the tiller with dead-white fingers.

“No, no,” he said, drawing back in horror. “Don’t touch me.” His eyes were wild, the stubble on his pale young cheeks flecked with blood and foam. “You have to sail there,” he said, as he pointed with one trembling finger over the prow of the boat. “There!” he said, demanding that Ana – a willful teenager, who had never been responsible for anything more than picking a frock – turn, and do what he, a farm boy no more than a few years her senior, was ordering.

Reluctantly she looked back, the ragged sail crackling above her head, and saw in the distance, beyond a cloud of fog, the indistinct outline of an island, dark and forbidding, rising from the sea. From the boat, it looked like a clenched fist, encircled by a misty-gray bracelet. Ana had never seen a more unwelcoming sight.

“Look for the fires,” he croaked. “They will light fires.”

“But I can’t sail the boat alone. You have to do it.”

Sergei shook his head and coughed so hard the blood ran between his fingers. He glanced down at his soiled hand, his eyes glazed, and whispered, “May God protect you, malenkaya.” And then, as calmly as if he were turning in bed, he rolled over the side of the boat and into the icy waters of the strait.

“Sergei!” she screamed, plunging toward the stern so abruptly she threatened to capsize the boat.

But he was already gone, floating off with his sealskin coat billowing out around him like the spread wings of a bat. For a few more seconds, he bobbed on the surface, riding the waves until the weight of his body and his boots and his clothes dragged him down. All that remained was a single wilted and frozen blue cornflower floating on the water.

The sight of it made her want to weep.

She was alone in the boat – alone in the world – and the tiller was already lurching wildly from one side to the other, screeching louder than the gulls swooping in and out of the fog. The hollow place in her heart, the place where she had already stored so many deaths, would now have to find room for Sergei’s, too.

How many more could she possibly be expected to hold there?

Clambering over the icy thwart, her fur coat as wet and heavy as armor, she perched on the little wooden seat in the stern. Even with her hood pulled low, the wind blew sleet and spray into her face. But at least the gusts were driving her toward the island. Her gloves were as stiff as icicles, and it was a struggle to loop the rope to the sail around one wrist, as she had seen Sergei do, and grasp the tiller with the other. The open boat cut through the waves, rising and falling, rising and falling. The fog surrounded her like a shroud, and she was so exhausted, so cold and so hungry, that she fell into a kind of stupor.

Her thoughts wandered to her garden in Tsarskoe Selo, the private enclave outside St. Petersburg, where she had grown her own roses, and to the fifteenth birthday party her parents had thrown for her there. It was only two years ago, a time before her life had gone from a dream to a nightmare. Now it seemed like something she must have imagined out of whole cloth. She thought of her sister, giving her a book of poems by her favorite writer – Pushkin – and her little brother sitting on his pony, as Nagorny, the rough sailor who had become his constant attendant, held the reins.

Her father, in his military uniform, had been standing stiffly on the verandah, holding her mother’s hand.

A wave dashed her full in the face, the frigid water running down her neck and under the collar of her coat. She shivered as the tiller threatened to slip out of her hand, and the rope attached to the sail cut into her wrist like a tourniquet. Her boots were slick with ice, and her bad foot had no feeling left in it at all.

But she also remembered, towering right behind her mother, the monk with the black eyes and the long, tangled beard. The bejeweled cross that he wore on his cassock, she was wearing now, under her corsets and coat; it had protected her from much, just as the monk had promised, but she doubted that even the cross would be enough to save her now.

As the boat came closer to the shore, it bucked like a horse trying to throw its rider, and she had to brace herself firmly against the stern. The slush in the hull was several inches deep and washed back and forth over whatever was left of her frozen provisions.

If she did not reach land tonight, she would surely follow poor Sergei into the freezing sea. Gulls and ospreys circled in the pewter sky, taunting her with their cries.

She pulled in on the sail, and the boat keeled, slicing through the waters. She was close enough now that she could see a jumble of boulders littering the beach and a dense wall of snow-covered forest just beyond them. But where were the fires that Sergei had promised? With the back of her sleeve, she wiped the seawater from her eyes – she had always been nearsighted but too vain to wear glasses. Dr. Botkin had once offered her a pair, at the house with the whitewashed windows, the house where …

No, she could not think about that. She had to keep her thoughts from straying there … especially now, when her life once again hung in the balance.

An osprey shot across the bow of the boat, then doubled back past the creaking mast, and as her eyes followed it, she saw a flickering glow – a torch as tall as a tree – burning on the cliffs ahead.

And then, squinting hard, she saw another.

Her heart rose in her chest.

There was a scraping sound as the surf dragged the bottom of the boat across a bed of sharp rocks and shells. She loosened her grip on the rope, and the sail swung wide, snapping as loud as a gunshot. She clung to the tiller with her frozen hands as the boat bumped and spun onto the wet sand and gravel, lodging there as the tide surged back out again.

She could barely move, but she knew that if she hesitated, the next wave could come in and pull her back out to sea again. Now, before her last ounce of strength abandoned her, she had to force herself to clamber to the front of the boat and step onto the island.

She got up unsteadily – her left foot as numb as a post – and struggled over the thwarts, the boat pitching and groaning beneath her. She thought she heard a bell clanging, a deep booming sound that reverberated off the rocks and trees. Touching the place on her breast where the cross rested, she murmured a prayer of thanks to St. Peter for delivering her from evil.

And then, nearly toppling over, she stepped into the water – which quickly rose above the tops of her boots – and staggered onto the beach. Her feet slipped and stumbled on the wet stones, but she crawled a few yards up the sand before allowing herself to fall to her knees. Her head was bowed, as if awaiting the blow of an axe, and her breath came only in ragged gasps. All she could hear was the ice crackling in her hair. But she was alive, and that was what mattered. She had survived the trek over the frozen tundra, the journey across the open sea … and the horrors of the house with the whitewashed windows. She had made it to a new continent, and as she peered down the beach, she could see dark shapes in the twilight, running toward her.

Yes, they were coming, to rescue her. Sergei had spoken the truth.

If she’d had the strength, she’d have called out to them, or waved an arm.

But her limbs had no feeling left in them, and her teeth were chattering in her skull.

The figures were coming so fast, and running so low, she could hardly believe her eyes.

And then she felt an even greater chill clutch at her heart, as she realized what the running shapes really were.

She whipped around toward the boat again, but it had already been dislodged and was disappearing into the fog.

Had she come so far … for this?

But she was too exhausted, too paralyzed with cold and despair, even to try to save herself.

She stared in terror down the beach as, shoulders heaving and eyes blazing orange in the dusk, the pack of ravening black wolves galloped toward her across the rocks and sand.

PART ONE

Chapter 1

KHAN NESHIN

Helmand Province, Afghanistan, July 10, 2011

“You okay, Major?”

Slater knew what he looked like, and he knew why Sergeant Groves was asking. He had taken a fistful of pills that morning, but the fever was back. He put out a hand to steady himself, then yanked it back off the hood of the jeep. The metal was as hot as a stove.

“I’ll survive,” he said, rubbing the tips of his fingers against his camo pants. That morning, he had visited the Marine barracks and watched as two more men had been airlifted out, both of them at death’s door; he wasn’t sure they’d make it. Despite all the normal precautions, the malaria, which he’d contracted himself a year before on a mission to Darfur, had decimated this camp. As a U.S. Army doctor and field epidemiologist, Major Frank Slater had been dispatched to figure out what else could be done – and fast.

The rice paddies he was looking at now were a prime breeding ground for the deadly mosquitoes, and the base had been built not only too close by, but directly downwind. At night, when they liked to feed, swarms of insects lifted off the paddies and descended en masse on the barracks and the canteen and the guard towers. Once, in the Euphrates Valley, Slater had seen a cloud of bugs rising so thick and high in the sky that he’d mistaken it for an oncoming storm.

“So, which way do you want to go with this?” Sergeant Groves asked. An African-American as tough and uncompromising as the Cleveland streets that he hailed from—“by the time I left, all we were making there was icicles,” he’d once told Slater – he always spoke with purpose and brevity. “Spray the swamp or move the base?”

Slater was debating that very thing when he was distracted by a pair of travelers – a young girl, maybe nine or ten, and her father – slogging through the paddy with an overburdened mule. Nearly everyone in Afghanistan had been exposed to malaria – it was as common as the flu in the rest of the world – and over the generations they had either died or developed a rudimentary immunity. They often got sick, but they had learned to live with it.

The young Americans, on the other hand, fresh from farms in Wisconsin and mountain towns in Colorado, didn’t fare as well.

The girl was leading the mule, while her father steadied the huge baskets of grain thrown across its scrawny back.

“I’m on it,” Private Diaz said, stepping out from the driver’s seat of the jeep. His M4 was already cradled in his hands. One thing the soldiers learned fast in the Middle East was that even the most innocuous sight could be their last. Baskets could carry explosives. Mules could be time bombs. Even kids could be used as decoys, or sacrificed altogether by the jihadis. On a previous mission, Slater had had to sort through the rubble of a girls’ school in Kandahar province after a Taliban, working undercover as a school custodian, had driven a motorcycle festooned with explosives straight into the classroom.

“Allahu Akbar!”the janitor had shouted with jubilation, “God is great!” just before blowing them all to kingdom come.

For the past ten years, Slater had seen death, in one form or another, nearly every day, but he still wasn’t sure which was worse – the fact that it could still shock him or the fact that on most days it didn’t. Just how hard, he often wondered, could a man let his heart become? How hard did it need to be?

The girl was looking back at him now with big dark eyes under her headscarf as she led the mule out of the paddy and up onto the embankment. The father switched at its rump with a hollow reed. The private, his rifle slung forward, ordered them to stop where they were. His Arabic was pretty basic, but the hand gesture and the loaded gun were universally understood.

Slater and Groves – his right-hand man on every mission he had undertaken from Iraq to Somalia – watched as Private Diaz approached them.

“Open the baskets,” he said, making a motion with one hand to indicate what he wanted. The father issued an order to his daughter, who flipped the lid off one basket, then waited as the soldier peered inside.

“The other one, too,” Diaz said, stepping around the mule’s lowered head.

The girl did as he ordered, standing beside the basket as Diaz poked the muzzle of his gun into the grain.

And just as Slater was about to order him to let them move along – was this any way to win hearts and minds? – a bright ribbon of iridescent green shot up out of the basket, fast as a lightning bolt, and struck the girl on the face. She went down as if hit by a mallet, writhing on the ground, and the private jumped back in surprise.

“Jesus,” he was saying over and over as he pointed the rifle futilely at the thrashing body of the girl. “It’s a viper!”

But Slater already knew that, and even as her father was wailing in terror, he was racing to her side. The snake still had its fangs buried in her cheek, secreting its venom, its tail shaking ferociously. Slater pulled his field knife from its scabbard – a knife he normally used to cut tissue samples from diseased cadavers – and with the other hand grabbed for the viper’s tail. Twice he felt its rough mottled surface, strong as a steel pipe, slip through his fingers, but on the third try he held it taut and was able to slice through the vertebrae. Half of the snake came away with a spill of blood, but the head was still fixed in its mortal bite.

The girl’s eyes were shut and her limbs were flailing, and it was only after Groves used his own broad hands to hold her down that Slater was able to pinch the back of the dying viper’s head and pull the fangs loose. The snake’s tongue flicked like a whip, but the light in its yellow eyes was fading. Slater pinched harder until the tongue slowed and the eyes lost their luster altogether. He tossed the carcass down the embankment, and Diaz, for good measure, unleashed a burst of shots from his rifle that rolled the coils down into the murky water.

“Get me my kit!” Slater hollered, and Diaz ran to the jeep.

Groves – as burly as a fullback but tender as a nurse – was crouched over the girl, examining the wound. There were two long gashes in her cheek, bloody smears on her tawny skin. The venom, some of the most powerful in the animal kingdom, was already coursing through her veins.

Her father, wailing and praying aloud, rocked on his sandaled feet. Even the mule brayed in dumb alarm.

Diaz handed Slater the kit, already open, and Slater, his hands moving on automatic pilot, went about administering the anticoagulant and doing his best to stabilize her, but he knew that only the antivenin, in short supply these days, could save the girl’s life.

And even then, only if it was used in the next hour.

“Round up the nearest chopper,” he said to Diaz. “We need to get this girl to the med center.”

But the soldier hesitated. “No offense, sir, but orders are that the med runs are only for military casualties. They won’t come for a civilian.”

Groves looked over at Slater with mournful eyes and said, “He’s right. Ever since that chopper was shot down three days ago, the orders have been ironclad. EMS duties are out.”

Slater heard them, but wondered if they were really prepared to stand by and let the girl die. Her father was screaming the few words of English he knew, “Help! U.S.A! Please, help!” He was on his knees in the dust, wringing his woven cap in his hands.

Her little heart was beating like a trip-hammer and her limbs were convulsing, and Slater knew that any further delay would seal the girl’s fate forever. Someone this size and weight, injected with a full dose of a pit viper’s poison – and he had seen enough of these snakes to know that this one had been fully mature – could not last long before her blood cells began to disintegrate.

“Keep her as still as you can,” he said to Groves and Diaz, then ran back to the jeep, grabbed the radio mike, and called it in to the main base.

“Marine down!” Slater said, “viper bite. Immediate – I say, immediate – evac needed!”

He saw Groves and the private exchange a glance.

“Your coordinates?” a voice on the radio crackled.

The coordinates? Slater, the blood pounding in his head from his own fever, fumbled to muster them. “We’re about two klicks from the Khan Neshin outpost,” he said, focusing as hard as he could, “just southwest of the rice paddies.”

Groves suddenly appeared at his side and grabbed the mike out of his hands, but instead of countermanding the major’s order, he gave the exact coordinates.

“Tell ’em they can finish the rations dump later,” Groves barked. “We need that chopper over here now! And tell the med center to get as much of the antivenin ready as they’ve got!”

Slater, his legs unsteady, crouched down in the shade of the jeep.

“You didn’t need to get mixed up in this,” Slater said after Groves signed off. “I’ll take the heat.”

“Don’t worry,” Groves said. “There’ll be plenty to go around.”

For the next half hour, Slater kept the girl as tranquilized as he could – the more she thrashed, the faster the poison circulated in her system – while the sergeant and the private kept a close watch on the neighboring fields. Taliban fighters were drawn to trouble like sharks to blood, and if they suspected a chopper was going to be flying in, they’d be scrambling through their stockpiles for one last Stinger missile. Nor did Slater want to go back to the outpost and ask for backup; somebody might see what was really going on and cancel the mission.

“I hear it!” Groves said, turning toward a low rise of scrubby hills.

So could Slater. The thrumming of its rotors preceded by only seconds the sight of the Black Hawk itself, soaring over the ridgeline. After doing a quick reconnaissance loop, the pilot put the chopper down a dozen yards from the jeep, its blades still spinning, its engine churning. The side hatch slid open, and two grunts with a stretcher leapt out into the cloud of dust.

“Where?” one shouted, wiping the whirling dirt from his goggles.

Diaz pointed to the girl lying low on the embankment between Slater and the sergeant.

The two soldiers stopped in their tracks, and over the loud rumble of the idling helicopter, one shouted, “A civilian?”

The other said, “Combat casualties only! Strict orders.”

“That’s right,” Slater said, tapping the major’s oak leaf cluster on his shirt, “and I’m giving them here! This girl is going to the med center, and she’s going now!”

The first soldier hesitated, still unsure, but the second one laid his end of the stretcher on the ground at her feet. “I’ve got a daughter back home,” he mumbled, as he wrapped the girl in a poncho liner, then helped Groves to lift her onto the canvas.

“I’m taking full responsibility,” Slater said. “Let’s move!”

But when the girl’s father tried to climb into the chopper, the pilot shook his head violently and waved his hand. “No can do!” he shouted. “We’re carrying too much weight already.”

Slater had to push the man away; there wasn’t time to explain. “Tell him what’s going on!” he shouted to the sergeant.

The father was screaming and crying – Diaz was trying to restrain him – as Slater slid the hatch shut and banged on the back of the pilot’s seat. “Okay, go, go, go!”

To evade possible fire, the chopper banked steeply to one side on takeoff, then zigzagged away from the rice paddies; these irrigated areas, called the green zone, were some of the deadliest terrain in Afghanistan, havens for snipers and insurgents. Slater heard a quick clattering on the bottom of the Black Hawk, a sound like typewriter keys clicking, and knew that at least one Taliban fighter had managed to get off a few rounds. The helicopter flew higher, soaring up and over the barren red hills, where the rusted carcasses of Soviet troop carriers could be seen half-buried in the dirt and sand. Now it would just be a race against time. The girl’s face was swollen up like she had the mumps, and Slater slipped the oxygen mask onto her as gently as he could. Her ears were like perfect little shells, he thought, as he looped the straps around the back of her head. She took no notice of what was being done, or where she was. She was delirious with the pain and the shock and the natural adrenaline that her body was instinctively pumping through her veins nonstop.

The soldiers stayed clear, strapped into their seats beside the ration pallets they’d been delivering and watching silently as Major Slater treated her. The one with the daughter looked like he was saying a prayer under his breath. But this little Afghan girl was Slater’s problem now, and they all knew it.

By the time the chopper cleared the med center perimeter and touched down, her eyes had shut, and when Slater lifted the lids, all he could see was the whites. Her limbs were pretty still, only occasionally rocked by sudden paroxysms as if jolts of electricity were shooting through her. Slater knew the signs weren’t good. It would have been different if he’d had the antivenin with him in the field, but it was costly stuff, in short supply, and it deteriorated rapidly if it wasn’t kept refrigerated.

Some of the staff at the med center looked surprised at the new admission – a local girl, when they’d been expecting a Marine – but Slater issued his orders with such conviction that not a second was lost. Covered with dirt and sweat, his fingers stained with snake blood, he was still clutching her limp hand as she was wheeled into the O.R., where the trauma team was ready with the IV lines.

“Careful when you insert those,” Slater warned. “The entry points are going to seep from the venom.”

“Major,” the surgeon said, calmly, “we know what we’re doing. We can take it from here.”

But when he tried to let go, the girl’s fingers feebly squeezed his own. Maybe she thought it was her dad.

“Hang in there, honey,” Slater said softly, though he doubted she could hear, or understand, him. “Don’t give up.” He extricated his fingers, and a nurse quickly brushed him aside so that she could get at the wound and sterilize the site. The surgeon took a syringe filled with the antivenin, held it up to the light, and expressed the air from the plunger.

Slater, knowing that he was simply in the way now, stepped outside and watched through the porthole in the swinging doors. The doctor and two nurses went through their paces with methodical precision and speed. But Slater was afraid that too much time had passed since the attack.

A shiver hit him, and he slumped into a crouch by the doors. This was the worst recurrence of the malaria he’d had in months, and the sudden blast of air-conditioning made him long for a blanket. But if he let on how bad it was, he could find himself restricted to desk duty in Washington – a fate he feared worse than death. He just needed to get back to his bunk, swallow some meds, and sweat it out for a day or two. The blood was beating in his temples like a drum.

And it got no better when he heard the voice of his commanding officer, Colonel Keener, bellowing from down the hall. “Did you call in this mission, Major Slater?”

“I did.”

“You did, sir.” Keener corrected him, glancing at a printout in his hand. “And you claimed this was a Marine? A Marine casualty?”

“I did,” he replied, “sir.”

“And you’re aware that we’re not an ambulance service? That you diverted a Black Hawk from its scheduled, combat-related run, to address a strictly civilian matter?” His frustration became more evident with every word he spoke. “Maybe you didn’t read the advisory – the one that was issued to all base personnel just two days ago?”

“Every word.”

Slater knew his attitude wasn’t helping his case, but he didn’t care. Truth be told, he hadn’t cared about protocols and orders and commands for years. He’d become a doctor so that he could save lives, pure and simple; he’d become an epidemiologist so that he could save thousands of lives, in some of the world’s worst places. But today, he was back to trying to save just one.

Just one little girl, with perfect little ears. And a father, off somewhere in Khan Neshin, no doubt begging Allah for a miracle … a miracle that wasn’t likely to be granted.

“You know, of course, that I will have to report this incident, and the AFIP is going to have to send out another staffer now to decide what to do about our malaria problem,” the colonel was saying. “That could take days, and cost us American lives.” He said the word “American” in such a way as to make it plain that they were all that counted in this world. “You may consider yourself off duty and restricted to the base, Doctor, until further notice. In case you don’t know it, you’re in some very deep shit.”

Slater had hardly needed to be told. While Keener stood there fuming, wondering what other threat he could issue, the major fished in his pocket for the Chloriquine tablets he was taking every few hours. He tried to swallow them dry, but his mouth was too parched. Brushing past the colonel, he staggered to the water fountain, got the pills down, then held his head under the arc of cool water. His scalp felt like a forest fire that was finally getting hosed down.

The surgeon came out of the O.R., looked at each one of them, then went to the colonel’s side and said something softly in his ear. The colonel nodded solemnly, and the surgeon ducked back inside the swinging doors.

“What?” Slater said, pressing his fingertips into his wet scalp. The water was running down the back of his neck.

“It looks like you blew your career for nothing,” Keener replied. “The girl just died.”

* * *

All that Slater remembered, later on, was the look on the colonel’s face – the look he’d seen on a hundred other official faces intent only on following orders – before he threw the punch that knocked the colonel off his feet. He also had a vague recollection of wobbling above him, as Keener lay there, stunned and speechless, on the grimy green linoleum.

But the actual punch, which must have been a haymaker, was a mystery.

Then he returned to the fountain and put his head back down under the spray. If there were tears still in him, he thought, he’d be shedding them now. But there weren’t any. They had dried up years ago.

From the far end of the hall, he could hear the sound of raised voices and running boots as the MPs rushed to arrest him.