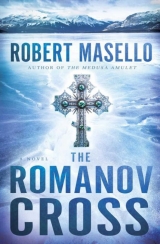

Текст книги "The Romanov Cross"

Автор книги: Robert Masello

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 35 страниц)

Chapter 2

The waters off the northern coast of Alaska were bad enough in summer, when the sun was shining around the clock and you could at least see the ice floes coming at you, but now – in late November, with a squall blowing in – they were about the worst place on earth to be.

Especially in a crab-catching tub like the Neptune II.

Harley Vane, the skipper, knew he’d be lucky just to keep the ship in one piece. He’d been fishing in the Bering Sea for almost twenty years, and both the crabbing and the storms had gotten worse the whole time. The crabbing he could figure out; his boat, and a dozen others, kept returning to the same spots, depleting the population and never giving it enough time to replenish itself. All the skippers knew they were committing a slow form of suicide, but nobody was going to be the first to stop.

And then there was the weather. The currents were getting stronger and more unpredictable all the time, the winds higher, the ice more broken up and difficult to avoid. He knew that all that global warming stuff was a load of crap – hadn’t the snowfall last year been the highest in five years? But judging from the sea-lanes, which were less frozen and more wide open than he had ever seen them, something was definitely afoot. As he sat in the wheelhouse, steering the boat through a turbulent ocean of fifteen-foot swells and hunks of glacier the size of cars, he had to buckle himself into his raised seat to keep from falling over. The rolling and pitching of the boat was so bad he considered reaching for the hand mike and calling the deckhands inside, but the Neptune’s catch so far had been bad – the last string of pots had averaged less than a hundred crabs each – and until their tanks were full, the boat would have to stay at sea. Back onshore, there were bills to pay, so he had to keep slinging the pots, no matter what.

“You want some coffee?” Lucas said, coming up from below with an extra mug in his hand. He was still wearing his yellow anorak, streaming with icy water.

“Christ Almighty,” Harley said, taking the coffee, “you’re soaking the place.”

“Yeah, well, it’s wet out there,” Lucas said. “You oughta try it sometime.”

“I tried it plenty,” Harley said. He’d worked the decks since he was eleven years old, back when his dad had owned the first Neptuneand his older brother had been able to throw the hook and snag the buoys. And he remembered his father sitting on a stool just like this, ruling the wheelhouse and looking out through the row of rectangular windows at the main deck of the boat. The view hadn’t changed much, with its ice-coated mast, its iron crane, its big gray buckets for sorting the catch. Once that boat had gone down, Harley and his brother Charlie had invested in this one. But unlike the original, the Neptune IIfeatured a double bank of white spotlights above the bridge. At this time of year, when the sun came out for no more than a few hours at midday, the lights threw a steady but white and ghostly glow over the deck. Sometimes, to Harley, it was like watching a black-and-white movie down there.

Now, from his perch, where he was surrounded by his video and computer screens – another innovation that his dad had resisted – he could see the four crewmen on deck throwing the lines, hauling in the pots with the crabs still clinging to the steel mesh, then emptying the catch into the buckets and onto the conveyor belt to the hold. An enormous wave – at least a twenty-five-footer – suddenly rose up, like a balloon inflating, and broke over the bow of the boat. The icy spray splashed all the way up to the windows of the wheelhouse.

“It’s getting too dangerous out there,” Lucas said, clinging to the back of the other stool. “We’re gonna get hit by a rogue wave bigger than that one, and somebody’s going overboard.”

“I just hope it’s Farrell, that lazy son of a bitch.”

Lucas took a sip of his own coffee and kept his own counsel.

Harley checked the screens. On one, he had a sonar reading that showed him what lay beneath his own rolling hull; right now, it was thirty fathoms of frigid black water, with an underwater sea mount rising half that high. On the others, he had his navigation and radar data, giving him his position and speed and direction. Glancing at the screens now, he knew what Lucas was about to say.

“You do know, don’t you, that you’re going to run right into the rock pile off St. Peter’s Island if you don’t change course soon?”

“You think I’m blind?”

“I think you’re like your brother. You’ll risk the whole damn boat to catch a full pot of crab.”

Although Harley didn’t say anything, he knew Lucas was right – at least about his brother. And about his dad, too, for that matter, may the old bastard rest in peace. There was a streak of crazy in those two – a streak that Harley liked to think he had avoided. That was why he was skipper now. But it didn’t mean he liked to be told what to do, much less by some college-boy deckhand who’d done maybe two or three seasons, max, on a crab boat. Harley stayed the course and waited for Lucas to dare to say another thing.

But he didn’t.

Down on the deck, Harley could see Kubelik and Farrell pulling up another pot – a steel cage ten feet square – this one brimming with crabs, hundreds of them scrabbling all over each other, their claws flailing, grasping at the mesh, struggling to escape. This was the first full pot Harley had seen in days, packed with keepers. When the bottom was dropped open, the crabs poured out onto the sorting counter, and the crewmen quickly went about throwing them into buckets, down the hole, or – in the case of those too mutilated or small to use – whipping them back into the ocean like Frisbees.

Harley didn’t care how close to St. Peter’s he got. If this was where the damn crabs were, this was where he was going.

For the next half hour, the Neptune IIsteamed ahead, throwing strings of pots and bucking the increasingly heavy seas. A chunk of ice broke off the crane and plummeted onto the deck, nearly killing the Samoan guy he’d hired in that waterfront bar. But every time Harley heard one of the deckhands shout into the intercom, “290 pounds!” or “300!” he resolved to keep on going. If this could just keep up, he could return to Port Orlov in a couple of days and not hear a word of bitching from his brother.

And then, if things really went his way, maybe he’d be able to convince Angie Dobbs to go someplace warm with him. L.A., or Miami Beach. He knew that he wasn’t enough of a draw all by himself – ten years ago, Angie had been runner-up for Miss Teen Alaska – but if he could promise her a free trip out of this hellhole, he figured she’d take it. And maybe even give him some action just to be polite. It wasn’t like she hadn’t been around – Christ, half the town claimed to have had her, and Harley had long felt unfairly overlooked.

“Skipper!” he heard over the intercom. Sounded like Farrell, probably about to complain about the length of the shift.

“What?” Harley said, unhappy at the break in his reverie.

“We got something!” he shouted over the howling wind.

“Yeah, I’ve been watching. You got the best damn catch of the season.”

“No,” Farrell said, “no, take a look!”

And now, lifting himself up from his seat to get a better view of the deck, Harley could see what Farrell, the hood thrown back on his yellow slicker, was wildly pointing at.

A box – big and black, with icy water cascading down its sides – was tangled in the hooks and lines, and with the help of a couple of the other crew members, it was being hauled over the railing. What the hell …

“I’ll be right down!” Harley called before turning to Lucas and telling him to hold the boat in position. “And do not fuck with the course.”

Harley grabbed his anorak off a hook on the wall. As he barreled down the narrow creaking stairs, he pulled a pair of thermal, waterproof gloves out of the pocket and wrestled them on. Just a few minutes out on deck unprotected and your fingers could freeze like fish sticks. Yanking the hood up over his head, he pulled the sliding door open, and was almost blown back into the cabin by the driving wind.

Forcing his way outside, the door slamming back into its groove behind him, he plowed up the deck with one hand clinging to the inside rail. Even in the gathering dusk, he could see, maybe three miles to starboard, the ragged silhouette of St. Peter’s Island sticking up out of the rolling sea. That one island, with its steep cliffs and rocky shoals, had claimed more lives than any other off the coast of Alaska, and he could see why even the native Inuit had always given it a wide berth. For as long as he could remember, they had considered it an unholy place, a place where unhappy and evil spirits, the ones who could not ride the highways of the Aurora Borealis up into the sky, were condemned to linger on earth. Some said that these doomed souls were the spirits of the mad Russians who had once colonized the island, and that they were now trapped in the bodies of the black wolves that roamed the cliffs. Harley could almost believe it.

“What do we do with it?” Farrell shouted as the great black box swung in the lines and netting overhead.

It was about six feet long, three feet wide, and its lid was carved with some design Harley couldn’t make out yet. The other crewmen were staring at it dumbfounded, and Harley directed the Samoan and a couple of others to get it down and onto the conveyor belt. Whatever it was, he didn’t want to lose it, and whatever might be inside it, he didn’t want the deckhands to find out before he did.

Farrell used a gaffing hook to pull the box clear of the railing, while the Samoan guided it onto the deck. It landed on one end with a loud thump, and a crack opened down the center of the lid. “Quick!” Harley said, lending a hand and pushing the box toward the belt. Harley guessed its weight at maybe two hundred waterlogged pounds, and once they had securely positioned it on the belt, Harley threw the switch and watched as it was carried the length of the deck, then down into the hold below.

“Okay, show’s over,” he shouted over the wind and crashing waves. “Haul in those pots! Now!”

Then, as the men cast one more look over their shoulders and returned to their labors, he went back toward the bridge. But instead of going up to the pilot’s cabin, he stumbled down the swaying steps to the hold, where he found the engineer, Richter, studying the box.

“What the hell is this?” Richter said. “You know you could have busted the belt with this damned thing?” Richter was usually just called the Old Man, and he’d worked on crab and cod and swordfish boats for nearly fifty years.

“I don’t know what it is,” Harley said. “It just came up in the lines.”

Richter, pulling at his bushy white eyebrows, stood back and surveyed the box, which had come to rest at the end of the now-stationary belt. Mutilated crabs, most of them dead but some of them still twitching, lay all over the wet floor. The overhead lights cast a sickly yellow glow around the huge holding tanks and roaring turbines. The air reeked of gasoline and brine.

“I’ll tell you what I think it is,” Richter said. “This damn thing is a coffin.”

Harley had reluctantly come to the same conclusion. It wasn’t built in the customary shape of a coffin, but the general dimensions were right.

“And you don’t want to bring coffins aboard,” Richter grumbled over the engine noise. “Didn’t your father teach you a goddamned thing?”

Harley was sick to death of hearing about his father. Everybody from Nome to Prudhoe Bay always had a story. He ran a hand over the lid of the box, brushing off some of the icy water, and bent closer to observe the carvings. Most of them had been worn away, but it looked like there was some writing here. Not in English, but in those characters he’d seen on the old Russian buildings that still remained here and there in Alaska. In school, they’d taught him about how the Russians had settled the area first, way back in the 1700s, and then, in one of the colossal blunders of all time, had sold it to the United States after the Civil War. This looked like that kind of writing, and in the dim light of the hold he could also make out a chiseled figure. Bending closer, he saw that it was sort of like a saint, but a really fierce-looking one, with a long robe, a short beard, and a key ring in one hand. He felt a sudden shudder descend his spine.

“Get me a flashlight,” he told the old man.

“What for?”

“Just get me one.”

Moving his head this way and that, trying to avoid throwing a shadow onto the box, Harley peered through the crack in the lid, and when Richter slapped a flashlight into his hand, he pointed the beam into the box and put his nose to the wood.

“God will punish you for what you’re doing.”

But Harley wasn’t listening. Although the crack was very narrow, he caught again a glimpse of something glistening inside the box. Something that glinted like a bright green eye.

Like an emerald.

“The dead oughta be left in peace,” Richter solemnly intoned.

On general grounds, Harley agreed. Still, it didn’t mean they got to hang on to their jewelry.

“What did you see in there?” the Old Man asked, finally overcome by his own curiosity. “Was it a native or a white man?”

“Can’t tell,” Harley replied, snapping off the flashlight and leaning back. “Too dark.” Nobody needed to know about this. Not yet. “Get me a tarp,” he said, and when the old man didn’t budge, he went and got one himself. He threw it over the box, then lashed it in place with heavy ropes. “Nobody touches this until we get back to port,” he said, and Richter conspicuously crossed himself.

Harley climbed the slippery stairs to the deck level, then up to the wheelhouse, where Lucas was still holding the course as ordered. But with Harley back, he couldn’t hold his tongue any longer.

“St. Peter’s Island,” he warned. “It’s less than a mile off the starboard prow. If we don’t steer clear of the rocks right now, they’re gonna rip the shit out of the boat.”

Harley took off his soaking gear and resumed his chair. In the pale moonlight, the island loomed like a gigantic black skull rising up out of the sea. A belt of fog clung to its shores like a shroud.

“Take us ten degrees west,” Harley said, and Lucas spun the wheel as fast as he could.

“What was that thing in the nets?” he asked, as the ship was buffeted by another crest of freezing water.

“You worry about the course,” Harley said, staring out at the dark sea. “Leave the rest to me.”

“I was just thinking, if it’s salvage of some kind, then it has to be reported to—”

The ship suddenly juddered from bow to stern, shaking like a dog throwing off water, and from deep below there was the sound of metal groaning. Lucas nearly slipped off his feet, as Harley clung to the control panel in front of him.

“Ice?” Harley said, though he already knew better. Lucas, wide-eyed and white with fear, said, “Rocks.”

A second jolt hit the ship, knocking it to one side, as waves swept the deck and the crab pots swung wildly in the air. One of them hit the Samoan, who, windmilling his arms in an attempt to regain his balance, was carried by the next surge over the side. Farrell and Kubelik were clinging desperately to the mast, the crane, and the icy ropes.

“Jesus Christ,” Harley said, groping for the hand mike.

Lucas was draped across the wheel as if it were a life preserver.

“Mayday!” Harley shouted into the microphone. “This is the Neptune II, northwest of St. Peter’s Island. Man overboard! Do you read me? Mayday!”

From belowdecks, there was another grinding sound, like sheet metal being crumpled in an auto yard, and the engineer, Richter, was bleating over the intercom. “The bulkhead’s breached! You hear me up there? The pumps won’t handle it!”

“We read you, Neptune,” a Coast Guard voice crackled over the mike. “You have a man overboard?”

“Yes,” Harley said, “and we’re taking on water!” He rattled off their position, then tossed the mike to Lucas, as he slipped off his stool.

“Don’t leave me here!” Lucas said, his voice strained and trembling.

“Handle it!” Harley shouted.

“Where the hell are you going?”

“Down below!” Harley answered, as he lurched toward the gangway. “To check the damage!” And something else.

As Lucas clung to the wheel, Harley scrambled down the steps. But he could tell already, just from the tilt of the deck and the terrible racket in the hold, that the ship was lost. He’d be lucky to escape this night alive. They all would.

Maybe Old Man Richter had been right about that damned box, after all.

Chapter 3

FORT LESLEY MCNAIR

Washington, D.C.

For a court-martial so hastily convened, Major Frank Slater thought things were moving along pretty smoothly.

Seated beside his Army-appointed lawyer – a kid with a blond crew cut and the look of someone who had seen more action in a Hooters than he had on any battlefield – Slater had nothing much to do besides sit there in his nice clean uniform and listen to the damning testimony that he neither denied nor apologized for.

Colonel Keener, whose duties in Afghanistan had been deemed too important to send him back to D.C. for the court-martial, testified against Slater by Skype. The computer monitor had been set up on a trolley in front of the panel of five military judges, and Slater and his attorney, Lieutenant Bonham, listened closely as the colonel related the various crimes and infractions that the major—“an epidemiologist,” Keener explained, as if he were labeling him a child molester, “who has no more business being in the Army than my dog does”—had committed in Khan Neshin.

Assaulting a superior officer – which fell under Article 128 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, Slater learned – was a slam-dunk for the prosecution. After Colonel Keener had made his initial statement, he was asked to stand by while corroborating evidence was supplied. That, too, was easy. A nurse had happened to be down the hall in the med center, and although she had been too far away to hear what the colonel had said to Slater just before the altercation, she had been flown back to the States to testify that she had indeed seen the major throw the punch that had decked the colonel.

“Just one punch?” the head judge, a retired general, asked.

“That’s all it took,” the nurse said.

Slater thought he saw a tiny smile crease the general’s lips.

“And then I called the MPs,” the nurse went on.

“And you have no knowledge of what transpired just before?” the judge asked.

“I found out later on,” she replied. “The little girl had died in the O.R., and the doctor – I mean, Major Slater – just lost it.” Hazarding a sympathetic glance at the defendant, she added, “It seemed like a really momentary thing … like he’d tried so hard to save her, and then, finding out that it was all for nothing, it just sort of tipped him over the edge.”

The general made a note, and the four other judges, all officers, followed his lead and did the same. Because it was a general court-martial – more serious in nature than either a summary or special trial – all told there were five officers deliberating, including three other old men and a woman who looked as if she’d swapped her spine for a ramrod. The prosecutor offered into evidence an X-ray, taken at the med center, of a fracture to Colonel Keener’s jawline. When it was shown to Slater for confirmation, he said, “It’s a good likeness.”

“What was that?” the general asked, cupping his ear.

“My client,” Lieutenant Bonham cut in, before handing the X-ray back to the bailiff, “says that he does not contest this exhibit.” Then he shot Slater a murderous look.

But once the assault and battery charge had been duly noted and the evidence entered into the records, the court moved on to what was considered – from the Army’s point of view – the even more serious charges. While punches got thrown all the time, especially in war zones, it wasn’t often that a commissioned officer issued an order that he knew to be a lie, and in so doing jeopardized a helicopter and its crew. When Slater had called in the mission from the rice paddies, he had not only made a False Official Statement (Article 107 of the code) – punishable with a dishonorable discharge, forfeiture of all pay and allowances, and confinement for a period of five years – but he had put military property and personnel at risk. (Article 108, among others.)

For Slater, the worst part of the proceeding wasn’t hearing all the charges leveled at him. That much he expected. No, the worst part was having to watch as his friend and right-hand man, Sergeant Jerome Groves, was forced to take the stand. Slater had already ordered Groves to tell the truth and let the blame fall entirely on his commanding officer, where it belonged, but he knew it would be tough. He and Groves had a long history together.

When the prosecutor leaned in and said, “Sergeant Groves, it was you who called in your exact coordinates to the air rescue – is that correct?” Groves hesitated, and Slater nodded at him to go on. No point in denying facts that were indisputable.

“Yes. But Major Slater was simply trying to save the—”

“And you knew,” the prosecutor went on, twirling his eyeglasses in one hand, “that the purpose of the mission was to airlift a civilian, not a member of the armed forces, to a medical facility?”

“All due respect, sir, but it was a kid,” Groves said. “What would you have done? She’d been bitten by a viper and she’d have—”

“I repeat,” the prosecutor interrupted again, “you knew it was not U.S. Army personnel?”

“I did.”

“And yet you remained a party to the deception?”

“On my orders!” Slater barked, lifting himself out of his chair. He was afraid that Groves was not going to muster enough of a defense. “The sergeant only did what I told him to do as his commanding officer. What I orderedhim to do.”

Predictably, Slater was ordered to sit down and shut up, in pretty much those words, or he would be removed from his own trial. After he sat back down, Lieutenant Bonham rose from his chair and conducted his own interrogation of the witness, advancing more or less the same argument, but in a legally reasoned, and more dispassionate, manner. Slater had given him explicit instructions to see to it that Groves was exonerated on all charges.

When the sergeant had been dismissed from the witness stand, he slunk by Slater’s chair and muttered, “Sorry, Frank,” as he passed.

“No reason to be,” Slater said.

The general in charge of the tribunal demanded again that there be no communication between the witnesses, and after shuffling his stack of papers, asked the lawyers to proceed to the summation.

The prosecutor, who looked confident that he had a winning hand, went through the litany of charges and all the articles of the military code that Slater had managed to break – even Slater was surprised that he’d managed to commit so many infractions in such a short space of time – before sitting down again with his hands folded over his abdomen like a guy waiting for the soufflé to be served.

Lieutenant Bonham stood up with a lot less confidence and proceeded to make his own arguments in defense of Major Slater. A lot of it was legal jargon, but Slater also had to sit still for a long recapitulation of his own military and medical accomplishments.

“May it be entered into the record that Major Slater enlisted in the United States Army thirteen years ago, with a medical degree from Johns Hopkins, a specialty in tropical and infectious diseases, and an advanced degree in statistics and epidemiology from the Georgetown University Program in Public Health. Those credentials have served him – and this country – exceptionally well in some of the most dangerous and hotly disputed scenes of engagement, ranging from Somalia to Sarajevo. He has earned three special commendations, a Purple Heart, and attained the rank of major, which he holds at the time of this hearing. He is also a victim of an especially chronic strain of malaria, to which he was exposed in the line of duty but which he has never allowed to interfere with the assignments given him by the United States Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, here in Washington, D.C., where he is based. This disease, I would argue, should be considered a mitigating factor for any possible misconduct. Among its symptoms are fevers, hallucinatory episodes, and insomnia – which in and of themselves can contribute to acts of an irrational and impulsive nature. Acts which Major Slater, if he had been wholly in control of his behavior, would never have countenanced, much less committed.”

Slater had to hand it to the kid. It was a very persuasive and well-put summation … even if he hated the part about the malaria. It wasn’t the malaria that made him throw that punch or call in the chopper. Right now, sitting comfortably in the courtroom, his illness at bay and his thoughts as clear as the blue November sky outside, he would have done exactly the same things all over again. And it wasn’t just the little Afghan girl that had done it – she was just the proverbial straw that had broken the camel’s back. This explosion had been building for years. He had seen too much horror, he had witnessed too many deaths, too many barbarities. He had flown to too many desolate corners of the earth, armed with too little to offer in the way of aid or relief. Under a mosquito net in Darfur, by the light of a bright moon, he had finally gotten around to reading Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and he had quickly understood why that volunteer from Oxfam had so urgently pressed the book on him. Maybe, without his noticing it, he had been turning into the mysterious character, Kurtz, a man who saw so much of the cruelty that man can inflict that it had finally driven him mad.

When Lieutenant Bonham had finished his appeal to the court, the general in charge of the tribunal ordered the room to be cleared so that the judges could deliberate, and Slater was taken back to a holding cell, where he was given a Coke, a bag of chips, and an egg salad sandwich wrapped in plastic.

“You hungry?” he said, sliding the sandwich toward his lawyer.

“Yes, but not that hungry.”

“What do you think our chances are?” he said, popping open the Coke.

“Guilty on all counts – that goes without saying.”

Slater knew he was right, but it still wasn’t exactly pleasant to hear.

“But there’s a lot of mitigating factors in your favor, so the sentencing could be light. And I think Colonel Keener has a certain reputation as a prick. That could help, too.” Gesturing at the bag of chips, Bonham said, “But if you’re not going to eat those …”

“Help yourself.”

Slater pushed his chair back and stared out the narrow window placed high in the wall and covered with chicken wire. It was about a foot and a half square. Nothing bigger than a beagle could have ever made it through.

Bonham checked his BlackBerry for messages, sent a few texts, then put it away. He polished off the potato chips and brushed his fingers clean with a hankie.

“There’s no reason to stick around in here on my account,” Slater said.

The lieutenant said, “Not much I can do anywhere else.”

“How long do you think it’ll be?”

“No telling.” Bonham drummed his fingers on the tabletop. “But maybe I could try to pry some news out of the bailiff.”

“You do that,” Slater said. But before the young lawyer closed the door behind him, he added, “You did a good job.”

Unexpectedly, Bonham glowed. “You think so, Major?”

“Yeah,” Slater said. “You just had a lousy case.”

Alone in the cell, Slater sipped the Coke and waited. A couple of rooms away, his fate was being decided by five judges who’d never even laid eyes on him before. It was a hard thought to hold in his head – that in a matter of minutes, maybe hours, he would learn, from the lips of a retired general, what the dire consequences of his actions might be. Reflecting on it all now, a month later and a world away, Slater couldn’t fault himself for what he did in trying to save the girl’s life. What else could he have done and still been able to face himself in the mirror? As for the punch … well, that was ill-advised, to say the least. And it wasn’t the first time his temper had gotten him into trouble. But whenever he remembered the look on the colonel’s face, the smug tone in which he’d announced the girl’s death … well, his fist went right back into a ball and he wanted to slug him again. Only this time he wanted to stay completely awake and aware the whole time.

The question was, would he still feel that way after serving five years in a military prison?

There was no clock in the holding cell. There was no phone, or TV, or magazine rack. The walls were cinder block, the door was steel. There was nothing for a prisoner to look at, nothing to do, except sit there and contemplate his destiny, which was something Slater had been doing everything he could to avoid.

He slumped forward and put his head down on the table – the wood was worn and scarred and the smell reminded him of his grammar-school classrooms – and closed his eyes. At night he could never sleep, but during the day his weariness often overwhelmed him. A few nights before, he had called his ex-wife, Martha, in Silver Spring. She hadn’t sounded all that happy to hear from him – and that was before he told her why he was stateside again. Once he had, he could hear her sigh, mostly in sympathy, but there was also a note of relief in it – relief that she had severed their relationship when she had, and that this latest act of self-immolation was not her problem anymore.

“Where are they keeping you?” she asked, and he had explained that he was free on his own recognizance until the trial began – though without a passport, he wasn’t going to go very far.

“Do you want me to come and see you?” she said. “Would that help?”

But he really didn’t see how it would. He had only called to let her know what was up, in case she ever got curious about his whereabouts … or the Army notified her that her portion of his Army pension would be severely diminished.