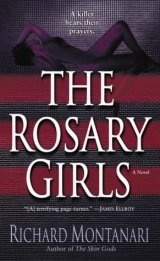

Текст книги "The Rosary Girls"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Маньяки

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

65

FRIDAY, 8:00 PM

The pain was exquisite, a slow rolling wave that inched up the back of his neck, then down. He popped a Vicodin, chased it with rancid water from the tap in the men’s room of a gas station in North Philly.

It was Good Friday. The day of the crucifixion.

Byrne knew that, one way or another, this was all probably coming to an end soon, probably tonight; and with it, he knew he would face something inside himself that had been there for fifteen years, something dark and violent and troubling.

He wanted everything to be in order.

He needed symmetry.

He had one stop to make first.

The cars were parked two deep on both sides of the street. In this part of the city, if the street was blocked, you didn’t call the police or knock on doors.You definitely didn’t want to blow your horn. Instead, you quietly put your car in reverse, and found another way.

The storm door of the ramshackle Point Breeze row house was open, all the lights burning inside. Byrne stood across the street, sheltered from the rain beneath the tattered awning of a shuttered bakery. Through the bay window across the street he could see the three pictures that graced the wall over the strawberry velvet Spanish modern sofa. Martin Luther King, Jesus, Muhammad Ali.

Right in front of him, in the rusted Pontiac, the kid sat alone in the backseat, completely oblivious to Byrne, smoking a blunt, rocking gently to whatever was coming through his headphones. After a few minutes he butted the blunt, opened the car door, and got out.

He stretched, flipped up the hood of his sweatshirt, straightened his baggies.

“Hey,” Byrne said. The pain in his head had settled into a dull metronome of agony, clicking loud and rhythmically at either temple. Still, it felt as if the mother of all migraines was just a car horn or flashbulb away.

The kid turned, surprised but not scared. He was about fifteen, tall and rangy, with the kind of body that would serve him pretty well in playground hoops, but take him no further. He wore the full Sean John uniform—full-cut jeans, quilted leather jacket, fleece hoodie.

The kid sized up Byrne, assessed the danger, the opportunity. Byrne kept his hands in plain sight.

“Yo,” the kid finally offered.

“Did you know Marius?” Byrne asked.

The kid gave him the twice-over. Byrne was way too big to mess with.

“MG was my boy,” the kid finally said. He flashed a JBM sign.

Byrne nodded. This kid could still go either way, he thought. There was a simmering intelligence behind his now bloodshot eyes. But Byrne got the feeling the kid was too busy fulfilling the world’s expectations of him.

Byrne reached slowly inside his coat—slowly enough to let this kid know there was nothing coming. He removed the envelope. The envelope was of a size and shape and heft that could only be one thing.

“His mother’s name is Delilah Watts?” Byrne asked. It was more like a statement of fact.

The kid glanced at the row house, at the bright bay window. A thin,

the Rosary girls 331

dark-skinned black woman in oversized gradient sunglasses and a deep auburn wig dabbed at her eyes as she received mourners. She was no more than thirty-five.

The kid turned back to Byrne. “Yeah.”

Byrne absently thumbed the rubber band around the fat envelope. He had never counted the contents. When he had taken it from Gideon Pratt that night, he had no reason to think it was a penny less than the five thousand dollars they had agreed upon. There was no reason to count it now.

“This is for Mrs. Watts,” Byrne said. He held the kid’s eyes for a few, flat seconds, a look that both of them had experienced in their time, a look that needed no embellishment, no footnoting.

The kid reached out, cautiously took the envelope. “She gonna want to know who it’s from,” he said.

Byrne nodded. Soon the kid understood that no answer was forthcoming.

The kid stuffed the envelope into his pocket. Byrne watched as he swaggered across the street, up to the house, stepped inside, hugged a few of the young men standing sentinel at the door. Byrne looked through the window as the kid waited briefly in the short receiving line. He could hear the strains of Al Green’s “You Brought the Sunshine” playing.

Byrne wondered how many times this scene would be played out across the country this night—too-young mothers sitting in too-hot parlors, presiding over the wake of a child given to the beast.

For all that Marius Green may have done wrong in his short life, for all the misery and pain he may have spread, there was only one reason he was in that alley that night, and that play had nothing to do with him.

Marius Green was dead, as was the man who killed him in cold blood. Was it justice? Perhaps not. But there was no doubt that it all began the day Deirdre Pettigrew met a terrible man in Fairmount Park, a day that had ended with another young mother with a ball of damp tissue in her hands, and a front room full of friends and family.

There is no solution, just resolution, Byrne thought. He was not a man who believed in karma. He was a man who believed in action and reaction.

Byrne watched as Delilah Watts opened the envelope. After the initial shock set in, she put her hand to her heart. She composed herself, then looked out the window, directly at him, directly into Kevin Byrne’s soul. He knew that she could not see him, that all she could see was the black mirror of night, and the rain-streaked reflection of her own pain.

Kevin Byrne bowed his head, then turned up his collar and walked into the storm.

FRIDAY, 8:25 PM

As Jessica drove home, the radio predicted a huge thunderstorm. High winds, lightning, flood warnings. Parts of Roosevelt Boulevard were already inundated.

She thought about the night she had met Patrick, so many years ago. She had watched him work in the ER that night, so impressed with his grace and confidence, his ability to comfort the people who came in those doors, looking for help.

People responded to him, believed in his ability to relieve their pain. His looks certainly didn’t hurt. She tried to think rationally about him. What did she really know? Was she able to think about him in the same terms she had thought about Brian Parkhurst?

No, she was not.

But the more she thought about it, the more it became possible. The fact that he was an MD, the fact that he could not account for his time at crucial intervals in the time line of the murders, the fact that he had lost his kid sister to violence, the fact that he was a Catholic, and, inescapably, the fact that he had treated all five girls. He knew their names and addresses, their medical histories.

She had looked again at the digital photographs of Nicole Taylor’s hand. Could Nicole have been spelling out f a r instead of p a r?

It was possible.

Despite her instincts, Jessica finally admitted it to herself. If she didn’t know Patrick, she would be leading the charge to arrest him, based on one immutable fact:

He knew all five girls.

FRIDAY, 8:55 PM

Byrne stood in the ICU watching Lauren Semanski.

The ER team had told him that Lauren had a lot of methamphetamine in her system, that she was a chronic user, and that when her abductor had injected her with the midazolam, it did not have quite

the effect it might have had if Lauren had not been full of a powerful stimulant.

Although they had not yet been able to talk to her, it was clear that Lauren Semanski’s injuries were consistent with those that might have been incurred by someone leaping from a moving vehicle. Incredibly, although her injuries were numerous and serious, except for the toxicity of the drugs in her system, none was life threatening.

Byrne sat down next to her bed.

He knew that Patrick Farrell was a friend of Jessica’s. He suspected that there was probably more to their relationship than mere friendship, but he would leave that for Jessica to tell him.

There had been so many false clues and blind alleys in this case so far. He was not sure that Patrick Farrell fit the mold, either. When he had met the man at the Rodin Museum crime scene, he had not gotten a feeling of any kind.

Still, that didn’t seem to matter much these days. Chances were good that he could shake hands with Ted Bundy and not have a clue. Everything pointed to Patrick Farrell. He’d seen many an arrest warrant issued on much less.

He took Lauren’s hand in his. He closed his eyes. The pain settled above his eyes, high and hot and murderous. Soon, the images detonated in his mind, shunting the breath in his lungs, and the door at the end of his mind swung wide...

FRIDAY, 8:55 PM

Scholars believe that a storm rose over Calvary on the day of Christ’s death, that the sky grew dark over the valley as He hung upon the cross.

Lauren Semanski had been very strong. Last year, when she tried to take her own life, I had looked at her and wondered why such a determined young woman would do such a thing. Life is a gift. Life is a blessing.Why had she tried to throw it all away?

Why had any of them tried to throw it away?

Nicole had lived with the ridicule of her classmates, an alcoholic father. Tessa had survived her mother’s lingering death, and faced her father’s slow

descent.

Bethany had been the object of scorn for her weight.

Kristi had problems with anorexia.

When I had treated them, I knew that I was cheating the Lord.They had set

themselves on a path and I had diverted them.

Nicole and Tessa and Bethany and Kristi.

Then there was Lauren. Lauren had survived her parents’ accident only

to walk out to the car one night, start the engine. She had brought her stuffed Opus with her, the plush little penguin toy her mother had given her for Christmas in the fifth year of her life.

Today she had resisted the midazolam. She was probably back on the meth. When she punched open the door we were moving at approximately thirty miles an hour. She jumped out. Just like that.There was far too much traffic for me to turn around and get her. I had to just let her go.

It is too late to change plans.

It is the Hour of None.

And although Lauren was the final mystery, another girl would do, one

with shiny curls and a halo of innocence around her head.

The wind picks up as I pull over, cut the engine. They predict a massive storm.There will be another storm tonight, a dark reckoning of the soul.

The light inside Jessica’s house . . .

. . . is bright and warm and inviting, a solitary ember in the dying coals of dusk.

He sits outside in a vehicle, sheltered from the rain. In his hands is a rosary. He thinks about Lauren Semanski, and how she got away. She was the fifth girl, the fifth mystery, the final piece in his masterwork.

But Jessica is here. He has business with her, too.

Jessica and her little girl.

He checks the items he has prepared: the hypodermic needles, the carpenter’s chalk, the sail maker’s needle and thread.

He prepares to step into the wicked night . . .

The imagery came and went, teasing with clarity, like the vision of a drowning man looking up from the bottom of a chlorinated pool. The pain in Byrne’s head was fierce. He walked out of ICU and into the parking lot, got into his car. He checked his weapon. Rain pelted his windshield.

He started his car and headed to the expressway.

Sophie was terrified of thunderstorms. Jessica knew where she’d gotten it, too. It was genetic. When Jessica was small, she used to hide under the steps at their house on Catharine Street whenever it thundered. If it got really bad, she used to crawl under the bed. Sometimes she would bring a candle. Until the day she set the mattress on fire.

They had eaten dinner in front of the television again. Jessica had been too tired to object. It didn’t matter anyway. She had picked at her food, disinterested in such a routine event when her world was cracking at the seams. Her stomach churned with the events of the day. How could she have been so wrong about Patrick?

Was she wrong about Patrick?

The images of what had been done to these young women would not leave her alone.

She checked the answering machine. There were no messages.

Vincent was staying with his brother. She picked up the phone and dialed the number. Well, two-thirds of it. Then she put the phone down.

Shit.

She did the dishes by hand, just to give her hands something to do. She poured a glass of wine, poured it out. She made a cup of tea, let it get cold.

Somehow, she’d made it until Sophie’s bedtime. Outside, thunder and lightning raged. Inside, Sophie was scared.

Jessica had tried all the usual remedies. She had offered to read her a story. No luck. She had asked Sophie if she wanted to watch Finding Nemo again. No luck. She didn’t even want to watch The Little Mermaid. This was rare. Jessica had offered to color her Peter Cottontail coloring book with her (no), offered to sing Wizard of Oz songs (no), offered to put decals on the colored eggs in the kitchen (no).

In the end, she just tucked Sophie into bed and sat with her. Every time there was a crack of thunder, Sophie looked at her as if it were the end of the world.

Jessica tried to think of anything but Patrick. So far, she had been unsuccessful.

There was a knock at the front door. It was probably Paula.

“I’ll be right back, sweetie.”

“No, Mom.”

“I won’t be more than—”

The power flickered off, then back on.

“That’s all we need.” Jessica stared at the table lamp as if she could will it to stay on. She held Sophie’s hand. The kid had her in a death grip. Mercifully, the lights stayed on. Thank you, Lord. “Mommy just has to answer the door. It’s Paula.You want to see Paula, don’t you?”

“I do.”

“I’ll be right back,” she said. “Gonna be okay?”

Sophie nodded, despite the fact that her lips were trembling.

Jessica kissed Sophie on the forehead, handed her Jools, her little brown bear. Sophie shook her head. Jessica then grabbed Molly, the beige one. Nope. It was hard to keep track. Sophie had good bears and bad bears. She finally said yes to Timothy, the panda.

“Be right back.”

“Okay.”

She walked down the stairs as the doorbell rang once, twice, three times. It didn’t sound like Paula.

“All right already,” she said.

She tried to look through the beveled glass in the door’s small window. It was pretty well fogged over. All she saw were the parking lights of the EMS van across the street. It seemed that even typhoons didn’t deter Carmine Arrabiata from having his weekly heart attack.

She opened the door.

It was Patrick.

Her first instinct was to slam the door. She resisted. For the moment. She glanced out at the street, looking for the surveillance car. She didn’t see it. She didn’t open the storm door.

“What are you doing here, Patrick?”

“Jess,” he said. “You’ve got to listen to me.”

The anger began to rise, dueling with her fears. “See, that’s the part you don’t seem to understand,” she said. “I really don’t.”

“Jess. Come on. It’s me.” He stamped from one foot to the other. He was thoroughly soaked.

“Me? Who the hell is me? You treated every one of these girls,” she said. “It didn’t occur to you to come forward with this information?”

“I see a lot of patients,” Patrick said. “You can’t expect me to remember them all.”

The wind was loud. Howling. They were both almost yelling to be heard.

“Bullshit. These were all within the last year.”

Patrick looked at the ground. “Maybe I just didn’t want to...”

“What, get involved? Are you fucking kidding me?”

“Jess. If you could just—”

“You shouldn’t be here, Patrick,” she said. “This puts me in a really awkward situation. Go home.”

“My God, Jess.You don’t really think I had anything to do with these, these...”

It was a good question, Jessica thought. In fact, it was the question.

Jessica was just about to answer when a crack of thunder boomed, and the power browned out. The lights flickered on, off, on.

“I...I don’t know what to think, Patrick.”

“Give me five minutes, Jess. Five minutes, and I’ll go.”

Jessica saw the world of pain in his eyes.

“Please,” he said. He was soaking wet, pitiful in his pleading.

Crazily, she thought about her weapon. It was in the hall closet upstairs, top shelf, where it always was. She was actually thinking about her weapon, and whether she could get to it in time if needed. Because of Patrick.

None of this seemed real.

“Can I at least come inside?” he asked.

There was no point in arguing. She cracked open the storm door as a sheer column of rain swept through. Jessica opened the door fully. She knew that there was a team on Patrick even if she didn’t see the car. She was armed and she had backup.

Try as she did, she just couldn’t believe Patrick was guilty. This wasn’t some crime of passion they were talking about, some moment of insanity when he lost his temper and went too far. This was the systematic, cold-blooded murder of six people. Maybe more.

Give her a piece of forensic evidence, and then she’d have no choice.

Until then...

The power went out.

Upstairs, Sophie wailed.

“Jesus Christ,” Jessica said. She looked across the street. Some of the houses still seemed to have power. Or was that candlelight?

“Maybe it’s the circuit breaker,” Patrick said, walking inside, walking past her. “Where’s the panel?”

Jessica looked at the floor, hands on hips. This was all too much.

“Bottom of the basement stairs,” she said, resigned. “There’s a flashlight on the dining room table. But don’t think that we—”

“Mommy!” from upstairs.

Patrick took off his raincoat. “I’ll check the panel, then I’m gone. I promise.”

Patrick grabbed the flashlight and headed to the basement.

Jessica shuffled her way to the steps in the sudden darkness. She headed upstairs, entered Sophie’s room.

“It’s okay, sweetie,” Jessica said, sitting on the edge of the bed. Sophie’s face looked tiny and round and frightened in the gloom. “Do you want to come downstairs with Mommy?”

Sophie shook her head.

“You sure?”

Sophie nodded. “Is Daddy here?”

“No, honey,” Jessica said, her heart sinking. “Mommy’s... Mommy’s going to get some candles, okay? You like candles.”

Sophie nodded again.

Jessica left the bedroom. She opened the linen closet next to the bathroom, felt her way through the box that held the hotel soaps and sample shampoos and conditioners. She remembered when she used to take long, luxurious bubble baths with scented candles scattered around the bathroom, back in the stone age of her marriage. Sometimes Vincent would join her. Somehow it seemed like someone else’s life at the moment. She found a pair of sandalwood candles. She took them out of the box, returned to Sophie’s room.

Of course, there were no matches.

“I’ll be right back.”

She went downstairs to the kitchen, her eyes somewhat adjusted to the dark. She rummaged in the junk drawer for some book matches. She found a pack. Matches from her wedding. She could feel the gold embossed jessica and vincent on the glossy cover. Just what she needed. If she believed in such things, she might imagine that there was a conspiracy afoot to drag her into some deep depression. She turned to head back upstairs when there was a slash of lightning and the sound of shattering glass.

She jumped at the impact. A branch had finally snapped off the dying maple next to the house and smashed in the window in the back door.

“Oh, this just gets better and better,” Jessica said. The rain swept into the kitchen. There was broken glass everywhere. “Son of a bitch.”

She got out a plastic trash bag from under the sink and some pushpins from the kitchen corkboard. Fighting the wind and gusting rain, she tacked the bag around the opening in the door, trying not to cut herself on the shards that remained.

What the hell was next?

She looked down the stairs into the basement, saw the Maglite beam dancing about the gloom.

She grabbed the matches and headed into the dining room. She looked through the drawers in the hutch, found a variety of candles. She lit half a dozen or so, placing them around the dining room and the living room. She headed back upstairs and lit the two candles in Sophie’s room.

“Better?” she asked.

“Better,” Sophie said.

Jessica reached out, dried Sophie’s cheeks. “The lights will be on in a little while. Okay?”

Sophie nodded, thoroughly unconvinced.

Jessica looked around the room. The candles did a fairly good job of exorcising the shadow monsters. She tweaked Sophie’s nose, got a minor giggle. She just got to the top of the stairs when the phone rang.

Jessica stepped into her bedroom, answered.

“Hello?”

She was met with an unearthly howl and hiss. Through it, barely: “It’s John Shepherd.”

He sounded as if he was on the moon. “I can barely hear you. What’s up?”

“You there?”

“Yes.”

The phone line crackled. “We just heard from the hospital,” he said.

“Say again?” Jessica said. The connection was horrible.

“Want me to call on your cell?”

“Okay,” Jessica said. Then she remembered. The cell was in the car. The car was in the garage. “No, that’s okay. Go ahead.”

“We just got a report back on what Lauren Semanski had in her hand.”

Something about Lauren Semanski. “Okay.”

“It was part of a ballpoint pen.”

“A what?”

“She had a broken ballpoint pen in her hand,” Shepherd shouted. “From St. Joseph’s.”

Jessica heard this clearly enough. She didn’t want to. “What do you mean?”

“It had the St. Joseph’s logo and address on it. The pen is from the hospital.”

Her heart grew cold in her chest. It couldn’t be true. “Are you sure?”

“No doubt about it,” Shepherd said. His voice was breaking up. “Listen... the surveillance team lost Farrell... Roosevelt is flooded all the way to—”

Quiet.

“John?”

Nothing. The phone line was dead. Jessica toggled the button on the phone. “Hello?”

She was met with a thick black silence.

Jessica hung up, stepped over to the hallway closet. She glanced down the stairs. Patrick was still in the basement.

She reached inside the closet, onto the top shelf, her mind spinning. He’s been asking about you, Angela had said.

She slipped the Glock out of the holster.

I was on my way to my sister’s house in Manayunk, Patrick had said, not twenty feet from Bethany Price’s still-warm body.

She checked the weapon’s magazine. It was full.

His doctor came to see him yesterday, Agnes Pinsky had said.

She slammed the magazine home, chambered a round. And began to descend the stairs.

The wind continued to bay outside, trembling the windowpanes in their cracked glazing.

“Patrick?”

No response.

She reached the bottom of the stairs, padded across the living room, opened the drawer in the hutch, grabbed the old flashlight. She pushed the switch. Dead. Of course. Thanks, Vincent.

She closed the drawer.

Louder: “Patrick?”

Silence.

This was getting out of control really fast. She wasn’t going into the cellar without light. No way.

She backed her way to the stairs, then made her way up as silently as she could. She would take Sophie and some blankets, bundle her up to the attic, and lock the door. Sophie would be miserable, but she would be safe. Jessica knew she had to get control of herself, and the situation. She would lock Sophie in, get to her cell phone, and call for backup.

“It’s okay, sweetie,” she said. “It’s okay.”

She picked up Sophie, held her tight. Sophie shivered. Her teeth chattered.

In the flickering candlelight, Jessica thought she was seeing things. She had to be mistaken. She picked up a candle, held it close.

She wasn’t mistaken. There, on Sophie’s forehead, was a cross made of blue chalk.

The killer wasn’t in the house.

The killer was in the room.

FRIDAY, 9:25 PM

Byrne pulled off Roosevelt Boulevard. The street was flooded. His head pounded, the images came roaring through, one after the other: a demented slaughterhouse of a slide show.

The killer was stalking Jessica and her daughter.

Byrne had looked at the lottery ticket the killer had put in Kristi Hamilton’s hands and not seen it at first. None of them had. When the lab uncovered the number, it became clear. The clue was not the lottery agent. The clue was the number.

The lab had determined that the Big 4 number the killer had chosen was 9–7–0–0.

The address of St. Katherine Church rectory was 9700 Frankford Avenue.

Jessica had been close. The Rosary Killer had defaced the door at St. Katherine three years ago and had fully intended to end his madness there tonight. He intended to take Lauren Semanski to the church and fulfill the final of the five Sorrowful Mysteries on the altar there. The crucifixion.

That Lauren had fought back and escaped only delayed him. When Byrne had touched the broken ballpoint pen in Lauren’s hand, he knew where the killer was ultimately headed, and who would be his final victim. He had immediately called the Eighth District, which had dispatched a half a dozen officers to the church and a pair of patrol cars to Jessica’s house.

Byrne’s only hope was that they were not too late.

The streetlights were out, as were the traffic lights. Accordingly, as always when things like this happened, everyone in Philly forgot how to drive. Byrne took out his cell phone and called Jessica again. He got a busy signal. He tried her cell phone. It rang five times, then switched over to her voice mail.

Come on, Jess.

He pulled over to the side of the road, closed his eyes. To anyone who had never experienced the exacting pain of a rampant migraine, there could be no explanation rich enough. The lights of the oncoming cars seared his eyes. Between the flashes, he saw the bodies. Not the chalk outlines of the crime scene after the sanitization of investigation, but rather the human beings.

Tessa Wells having her arms and legs positioned around the pillar.

Nicole Taylor being laid to rest in the field of bright flowers.

Bethany Price and her crown of razors.

Kristi Hamilton soaked with blood.

Their eyes were open, questioning, pleading.

Pleading with him.

The fifth body was not clear to him at all, but he knew enough to shake him to the bottom of his soul.

The fifth body was just a little girl.

FRIDAY, 9:35 PM

Jessica slammed shut the bedroom door. Locked it. She had to begin with the immediate area. She searched beneath the bed, behind the curtains, in the closet, her weapon out front.

Empty.

Somehow Patrick had gotten upstairs and made the sign of the cross on Sophie’s forehead. She had tried to ask Sophie a gentle question about it, but her little girl seemed traumatized.

The idea made Jessica as sick as it did enraged. But at the moment, rage was her enemy. Her life was under siege.

She sat back down on the bed.

“You have to listen to Mommy, okay?”

Sophie stared, as if she was in shock.

“Sweetie? Listen to Mommy.”

Silence from her daughter.

“Mommy is going to make up a bed in the closet, okay? Like camping. Okay?”

Sophie had no reaction.

Jessica scrambled over to the closet. She pushed everything to the back, yanked the bedclothes off the bed, and created a makeshift bed. It broke her heart to have to do this, but she had no choice. She pulled everything else out of the closet and tossed it on the floor, everything that might cause Sophie harm. She lifted her daughter out of the bed, fighting her own tears of fury and terror.

She kissed Sophie, then closed the closet door. She turned the church key, pocketed it. She grabbed her weapon, and exited the room.

All the candles she had lighted in the house were blown out. The wind howled outside, but in the house it was deathly quiet. It was an intoxicating dark, a dark that seemed to consume everything it touched. Jessica saw everything she knew to be there in her mind, not with her eyes. As she moved down the stairs, she considered the layout of the living room. The table, the chairs, the hutch, the armoire that held the TV and the audio and video equipment, the love seats. It was all so familiar and all so foreign at the same moment. Each shadow held a monster; each outline, a threat.

She had qualified at the range every year she had been a cop, had taken the tactical, live-fire training course. But it was never supposed to be her house, her refuge from the insane world outside. This was the place where her little girl played. Now it had become a battleground.

When she touched the last step, she realized what she was doing. She was leaving Sophie alone upstairs. Had she really cleared the entire floor? Had she looked everywhere? Had she eliminated every possibility of threat?

“Patrick?” she said. Her voice sounded weak, plaintive. No answer.

Cold sweat latticed her back and shoulders, trickling to her waist. Then, loud, but not loud enough to frighten Sophie: “Listen. Patrick.

I’ve got my weapon in my hand. I’m not fucking around. I need to see you out here right now. We go downtown, we work this out. Don’t do this to me.”

Cold silence.

Just the wind.

Patrick had taken her Maglite. It was the only working flashlight in the house. The wind rattled the windowpanes in their mullions, resulting in a low, keening wail that sounded like a hurt animal.

Jessica stepped into the kitchen, trying her best to focus in the gloom. She moved slowly, keeping her left shoulder to the wall, the side opposite her shooting hand. If she had to, she could put her back to the wall and swing the weapon 180, protecting her rear flank.

The kitchen was clear.

Before she rolled the jamb, into the living room, she stopped, listened, cocking her ear to the night sounds. Was someone moaning? Crying? She knew it wasn’t Sophie.

She listened, searching the house for the sound. It was gone.

From the opening in the back door, Jessica smelled the scent of rain on early-spring soil, earthen and damp. She stepped forward in the darkness, her foot crunching the broken glass on the kitchen floor. The wind kicked, flapping the edges of the black plastic bag pinned over the opening.

When she edged back into the living room, she remembered that her laptop computer was on the small desk. If she wasn’t mistaken, and if any luck could be found this night, the battery was fully charged. She edged over to the desk, opened the laptop. The screen kicked to life, flickered twice, then threw a milky blue light across the living room. Jessica shut her eyes tightly for a few seconds, then opened them. It was enough light to see. The room opened before her.