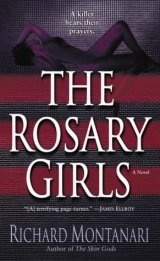

Текст книги "The Rosary Girls"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Маньяки

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

This book has been optimized for viewing at a monitor setting of 1024 x 768 pixels.

Also by Richard Montanari

Kiss of Evil The V iolet Hour Deviant Way

Richard montanari

ball antine b o oks T new york

a novel The Rosary Girls is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales,

or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2005 by Richard Montanari

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Ballantine and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the publisher upon request.

ee48203-4

Ballantine Books website address: www.ballantinebooks.com

Text design by Susan Turner

v1.0

FOR DJC Cuor forte rompe cattiva sorte.

the Rosary girls

PALM SUNDAY, 11:55 PM

There is a wintry sadness about this one, a deep-rooted melancholy that belies her seventeen years, a laugh that never fully engages any sort of inner joy. Perhaps there is none.

You see them all the time on the street; the one walking alone, books clutched tightly to her breast, eyes cast earthward, ever adrift in thought. She is the one strolling a few paces behind the other girls, content to accept the rare morsel of friendship tossed her way.The one who babysits her way through all the milestones of adolescence.The one who refuses her beauty, as if it were elective.

Her name is Tessa Ann Wells.

She smells like fresh-cut flowers.

“I cannot hear you,” I say.

“. . . lordaswiddee,” comes the tiny voice from the chapel. It sounds as if I have awakened her, which is entirely possible. I took her early Friday morning, and it is now nearly midnight on Sunday. She has been praying in the chapel, more or less nonstop.

4 Richard montanari

It is not a formal chapel, of course, merely a converted closet, but it is outfitted with everything one needs for reflection and prayer.

“This will not do,” I say.“You know that it is paramount to derive meaning from each and every word, don’t you?”

From the chapel:“Yes.”

“Consider how many people around the world are praying at this very moment.Why should God listen to those who are insincere?”

“No reason.”

I lean closer to the door.“Would you want the Lord to show you this sort of contempt on the day of rapture?”

“No.”

“Good,” I reply.“What decade?”

It takes a few moments for her to answer. In the darkness of the chapel, one must proceed by feel.

Finally, she says:“Third.”

“Begin again.”

I light the remainder of the votives. I finish my wine. Contrary to what many believe, the rites of the sacraments are not always solemn undertakings, but rather are, many times, cause for joy and celebration.

I am just about to remind Tessa when, with clarity and eloquence and import, she begins to pray once more:

“Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee . . .”

Is there a sound more beautiful than a virgin at prayer?

“Blessed art thou amongst women . . .”

I glance at my watch. It is just after midnight.

“And blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus . . .”

It is time.

“Holy Mary, mother of God . . .”

I take the hypodermic from its case.The needle gleams in the candlelight. The Holy Spirit is here.

“Pray for us sinners . . .”

The Passion has begun.

“Now and at the hour of our death . . .”

I open the door and step into the chapel.

Amen.

pa rt o n e 1

MONDAY, 3:05 A M

There is an hour known intimately to all who rouse to meet it, a time when darkness sheds fully the cloak of twilight and the streets fall still and silent, a time when shadows convene, become one, dissolve. A time when those who suffer disbelieve the dawn.

Every city has its quarter, its neon Golgotha.

In Philadelphia, it is known as South Street.

This night, while most of the City of Brotherly Love slept, while the

rivers flowed mutely to the sea, the flesh peddler rushed down South Street like a dry, blistering wind. Between Third and Fourth Streets he pushed through a wrought-iron gate, walked down a narrow alleyway, and entered a private club called Paradise. The handful of patrons scattered about the room met his gaze, then immediately averted their eyes. In the peddler’s stare they saw a portal to their own blackened souls, and knew that if they engaged him, even for a moment, the understanding would be far too much to bear.

To those who knew his trade, the peddler was an enigma, but not a puzzle anyone was eager to solve.

He was a big man, well over six feet tall, with a broad carriage and large, coarse hands that promised reckoning to those who crossed him. He had wheat-colored hair and cold green eyes, eyes that would spark to bright cobalt in candlelight, eyes that could take in the horizon with one glance, missing nothing. Above his right eye was a shiny keloid scar, a ridge of ropy tissue in the shape of an inverted V. He wore a long black leather coat that strained against the thick muscles in his back.

He had come to the club five nights in a row now, and this night he would meet his buyer. Appointments were not easily made at Paradise. Friendships were unknown.

The peddler sat at the back of the dank basement room at a table that, although not reserved for him, had become his by default. Even though Paradise was settled with players of every dark stripe and pedigree, it was clear that the peddler was of another breed.

The speakers behind the bar offered Mingus, Miles, Monk; the ceiling: soiled Chinese lanterns and rotary fans covered in wood-grain contact paper. Cones of blueberry incense burned, wedding the cigarette smoke, graying the air with a raw, fruity sweetness.

At three ten, two men entered the club. One was the buyer; the other, his guardian. They both met the eyes of the peddler. And knew.

The buyer, whose name was Gideon Pratt, was a squat, balding man in his late fifties, with flushed cheeks, restless gray eyes, and jowls that hung like melted wax. He wore an ill-fitting three-piece suit and had fingers long-gnarled by arthritis. His breath was fetid. His teeth, ocher and spare.

Behind him walked a bigger man—bigger even than the peddler. He wore mirrored sunglasses and a denim duster. His face and neck were ornamented with an elaborate web of ta moko, the Maori tribal tattoos.

Without a word, the three men gathered, then walked down a short hallway to a supply room.

The back room at Paradise was cramped and hot, packed with boxes of off-brand liquor, a pair of scarred metal desks, and a mildewed, ragged sofa. An old jukebox flickered carbon-blue light.

Once in the room, door closed, the large man, who went by the street name of Diablo, roughly patted down the peddler for weapons and wires, attempting to establish a stratum of power. As he was doing this, the peddler noted the three-word tattoo at the base of Diablo’s neck. It read: mongrel for life. He also noticed the butt of a chrome Smith & Wesson revolver in the large man’s waistband.

Satisfied that the peddler was unarmed and wore no listening devices, Diablo stepped away, behind Pratt, crossed his arms, and observed.

“What do you have for me?” Pratt asked.

The peddler considered the man before answering him. They had reached the moment that occurs in every transaction, the instant when the purveyor must come clean and lay his wares upon the velvet. The peddler reached slowly into his leather coat—there would be no furtive moves here—and removed a pair of Polaroid pictures. He handed them to Gideon Pratt.

Both photographs were of fully clothed, suggestively posed teenaged black girls. The one called Tanya sat on the front stoop of her row house, blowing a kiss to the photographer. Alicia, her sister, vamped on the beach in Wildwood.

As Pratt scrutinized the photos, his cheeks flared crimson for a moment, his breath hitched in his chest. “Just... beautiful,” he said.

Diablo glanced at the snapshots, registering no reaction. He turned his gaze back to the peddler.

“What is her name?” Pratt asked, holding up one of the photos.

“Tanya,” the peddler replied.

“Tan-ya,” Pratt repeated, separating the syllables, as if to sort the essence of the girl. He handed one of the pictures back, then glanced at the photograph in his hand. “She is adorable,” he added. “A mischievous one. I can tell.”

Pratt touched the photograph, running his finger gently over the glossy surface. He seemed to drift for a moment, lost in some reverie, then put the picture into his pocket. He snapped back to the moment, back to the business at hand. “When?”

“Now,” the peddler replied.

Pratt reacted with surprise and delight. He had not expected this. “She is here?”

The peddler nodded.

“Where?” asked Pratt.

“Nearby.”

Gideon Pratt straightened his tie, adjusted the vest over his bulging stomach, smoothed what little hair he had. He took a deep breath, finding his axis, then gestured to the door. “Shall we?”

The peddler nodded again, then looked to Diablo for permission. Diablo waited a moment, further cementing his status, then stepped to the side.

The three men exited the club, walked across South Street to Orianna Street. They continued down Orianna, emerging into a small parking lot between the buildings. In the lot were two vehicles: a rusted van with smoked-glass windows and a late-model Chrysler. Diablo put a hand up, strode forward, and looked into the windows of the Chrysler. He turned, nodded, and Pratt and the peddler stepped up to the van.

“You have the payment?” the peddler asked.

Gideon Pratt tapped his pocket.

The peddler looked briefly between the two men, then reached into the pocket of his coat and retrieved a set of keys. Before he could insert the key into the van’s passenger door, he dropped them to the ground.

Both Pratt and Diablo instinctively looked down, momentarily distracted.

In the following, carefully considered instant, the peddler bent down to retrieve the keys. Instead of picking them up, he closed his hand around the crowbar he had placed behind the right front tire earlier in the evening. When he arose, he spun on his heels and slammed the steel bar into the center of Diablo’s face, exploding the man’s nose into a thick scarlet vapor of blood and ruined cartilage. It was a surgically delivered blow, perfectly leveraged, one designed to cripple and incapacitate but not kill. With his left hand the peddler removed the Smith & Wesson revolver from Diablo’s waistband.

Dazed, momentarily bewildered, operating on animal instinct instead of reason, Diablo charged the peddler, his field of vision now clouded with blood and involuntary tears. His forward motion was met with the butt of the Smith & Wesson, swung with the full force of the peddler’s considerable strength. The blow sent six of Diablo’s teeth into the cool night air, then clacking to the ground like so many spilled pearls.

Diablo folded to the pitted asphalt, howling in agony.

A warrior, he rolled onto his knees, hesitated, then looked up, anticipating the deathblow.

“Run,” the peddler said.

Diablo paused for a moment, his breath now coming in staggered, sodden gasps. He spit a mouthful of blood and mucus. When the peddler cocked the hammer of the weapon and placed the tip of the barrel to his forehead, Diablo saw the wisdom of obeying the man’s order.

With great effort, he arose, staggered down the road toward South Street, and disappeared, never once taking his eyes from the peddler.

The peddler then turned to Gideon Pratt.

Pratt tried to strike a pose of menace, but this was not his gift. He was facing a moment all murderers fear, a brutal computation of his crimes against man, against God.

“Wh-who are you?” Pratt asked.

The peddler opened the back door of the van. He calmly deposited the gun and the crowbar, and removed a thick, cowhide belt. He wrapped his knuckles in the hard leather.

“Do you dream?” the peddler asked.

“What?”

“Do...you... dream?”

Gideon Pratt fell speechless.

For Detective Kevin Francis Byrne of the Philadelphia Police Department’s Homicide Unit, the answer was a moot point. He had tracked Gideon Pratt for a long time, and had lured him into this moment with precision and care, a scenario that had invaded his dreams.

Gideon Pratt had raped and murdered a fifteen-year-old girl named Deirdre Pettigrew in Fairmount Park, and the department had all but given up on solving the case. It was the first time Pratt had killed one of his victims, and Byrne had known that it would not be easy to draw him out. Byrne had invested a few hundred hours of his own time and many a night’s sleep in anticipation of this very second.

And now, as dawn remained a dim rumor in the City of Brotherly Love, as Kevin Byrne stepped forward and landed the first blow, came his receipt.

Twenty minutes later they were in a curtained emergency room at Jefferson Hospital. Gideon Pratt stood dead center, Byrne to one side, a staff intern named Avram Hirsch on the other.

Pratt had a knot on his forehead the size and shape of a rotted plum, a bloodied lip, a deep purple bruise on his right cheek, and what might have been a broken nose. His right eye was nearly swollen shut. The front of his formerly white shirt was a deep brown, caked with blood.

As Byrne looked at the man—humiliated, demeaned, disgraced, caught—he thought about his own partner in the Homicide Unit, a daunting piece of ironwork named Jimmy Purify. Jimmy would have loved this, Byrne thought. Jimmy loved the characters, of which Philly seemed to have an endless supply. The street professors, the junkie prophets, the hookers with hearts of marble.

But most of all, Detective Jimmy Purify loved catching the bad guys. The worse the man, the more Jimmy savored the hunt.

There was no one worse than Gideon Pratt.

They had tracked Pratt through an extensive labyrinth of informants, had followed him through the darkest veins of Philadelphia’s netherworld of sex clubs and child pornography rings. They had pursued him with the same sense of purpose, the same focus and rabid intent with which they had stepped out of the academy so many years earlier.

Which was just the way Jimmy Purify liked it.

It made him feel like a kid again, he said.

In his day Jimmy had been shot twice, run over once, beaten far too many times to calculate, but it was a triple bypass that finally took him out. While Kevin Byrne was so pleasantly engaged with Gideon Pratt, James “Clutch” Purify was resting in a post-op room in Mercy Hospital, tubes and drip lines snaking out of his body like Medusa’s snakes.

The good news was that Jimmy’s prognosis looked good. The sad news was that Jimmy thought he was coming back to the job. He wasn’t. No one ever did from a triple. Not at fifty. Not in Homicide. Not in Philly.

I miss you, Clutch, Byrne thought, knowing that he was going to meet his new partner later that day. It just ain’t the same without you, man.

It never will be.

Byrne had been there when Jimmy went down, not ten, powerless feet away. They had been standing near the register at Malik’s, a hole-inthe-bricks hoagie shop at Tenth and Washington. Byrne had been loading their coffees with sugar while Jimmy had been macking the waitress, Desiree, a young, cinnamon-skinned beauty at least three musical styles Jimmy’s junior and five miles out of his league. Desiree was the only real reason they ever stopped at Malik’s. It sure as hell wasn’t the food.

One minute Jimmy had been leaning against the counter, his younggirl rap firing on all eight, his smile on high beam. The next minute he was on the floor, his face contorted in pain, his body rigid, the fingers of his huge hands curling into claws.

Byrne had frozen that instant in his mind, the way he had stilled few others in his life. Over his twenty years on the force, he had found it almost routine to accept the moments of blind heroism and reckless courage in the people he loved and admired. He had even come to accept the senseless, random acts of savagery delivered by and unto strangers. These things came with the job: the steep premium to justice sought. It was the moments of naked humanity and weakness of flesh, however, he could not elude, the images of body and spirit betrayed that burrowed beneath the surface of his heart.

When he saw the big man on the muddied tile of the diner, his body skirmishing with death, the silent scream slashed into his jaw, he knew that he would never look at Jimmy Purify the same way again. Oh, he would love him, as he had come to over the years, and he would listen to his preposterous stories, and he would, by the grace of God, once again marvel at Jimmy’s lithe and fluid abilities behind a gas grill on those sweltering Philly summer Sundays, and he would, without a moment’s thought or hesitation, take a bullet to the heart for the man, but he knew immediately that this thing they did—the unflinching descent into the maw of violence and insanity, night after night—was over.

As much as it brought Byrne shame and regret, that was the reality of that long, terrible night.

The reality of this night, however, found a dark balance in Byrne’s mind, a delicate symmetry that he knew would bring Jimmy Purify peace. Deirdre Pettigrew was dead, and Gideon Pratt was going to take the full ride. Another family was shredded by grief, but this time the killer had left behind his DNA in the form of a gray pubic hair that would send him to the little tiled room at SCI Greene. There Gideon Pratt would meet the icy needle if Byrne had anything to say about it. Of course, the justice system being what it was, there was a fifty–fifty chance that, if convicted, Pratt would get life without parole. If that turned out to be the case, Byrne knew enough people in prison to finish the job. He would call in a chit. Either way, the sand was running on Gideon Pratt. He was in the hat.

“The suspect fell down a flight of concrete steps while he attempted to evade arrest,” Byrne offered to Dr. Hirsch.

Avram Hirsch wrote it down. He may have been young, but he was from Jefferson. He had already learned that, many times, sexual predators were also quite clumsy, and prone to tripping and falling. Sometimes they even had broken bones.

“Isn’t that right, Mr. Pratt?” Byrne asked.

Gideon Pratt just stared straight ahead.

“Isn’t that right, Mr. Pratt?” Byrne repeated.

“Yes,” Pratt said.

“Say it.”

“While I was running away from the police, I fell down a flight of steps and caused my injuries.”

Hirsch wrote this down, too.

Kevin Byrne shrugged, asked: “Do you find that Mr. Pratt’s injuries are consistent with a fall down a flight of concrete steps, Doctor?”

“Absolutely,” Hirsch replied.

More writing.

On the way to the hospital, Byrne had had a discussion with Gideon Pratt, imparting the wisdom that what Pratt had experienced in that parking lot was merely a taste of what he could expect if he considered a charge of police brutality. He had also informed Pratt that, at that moment, Byrne had three people standing by who were willing to go on the record that they had witnessed the suspect tripping and falling down the stairs while being chased. Upstanding citizens, all.

In addition, Byrne disclosed that, while it was only a short ride from the hospital to the police administration building, it would be the longest few minutes of Pratt’s life. To make his point, Byrne had referenced a few of the tools in the back of the van: the saber saw, the surgeon’s ribcracker, the electric shears.

Pratt understood.

And he was now on the record.

A few minutes later, when Hirsch pulled down Gideon Pratt’s pants and stained underwear, what Byrne saw made him shake his head. Gideon Pratt had shaved off his pubic hair. Pratt looked down at his groin, back up at Byrne.

“It’s a ritual,” Pratt said. “A religious ritual.”

Byrne exploded across the room. “So’s crucifixion, shithead,” he said. “What do you say we run down to Home Depot for some religious supplies?”

At that moment Byrne caught the intern’s eyes. Dr. Hirsch nodded, meaning, they’d get their sample of pubic hair. Nobody could shave that close. Byrne picked up on the exchange, ran with it.

“If you thought your little ceremony was gonna stop us from getting a sample, you’re officially an asshole,” Byrne said. “As if that was in some doubt.” He got within inches of Gideon Pratt’s face. “Besides, all we had to do was hold you until it grew back.”

Pratt looked at the ceiling and sighed.

Apparently that hadn’t occurred to him.

Byrne sat in the parking lot of the police administration building, braking from the long day, sipping an Irish coffee. The coffee was cop-shop rough. The Jameson paved it.

The sky was clear and black and cloudless above a putty moon. Spring murmured.

He’d steal a few hours sleep in the borrowed van he had used to lure

Gideon Pratt, then return it to his friend Ernie Tedesco later in the day. Ernie owned a small meat packing business in Pennsport.

Byrne touched the wick of skin over his right eye. The scar felt warm and pliant beneath his fingers, and spoke of a pain that, for the moment, was not there, a phantom grief that had flared for the first time many years earlier. He rolled down the window, closed his eyes, felt the girders of memory give way.

In his mind, that dark recess where desire and revulsion meet, that place where the icy waters of the Delaware River raged so long ago, he saw the last moments of a young girl’s life, saw the quiet horror unfold...

. . . sees the sweet face of Deirdre Pettigrew. She is small for her age, naïve for her time. She has a kind and trusting heart, a sheltered soul. It is a sweltering day, and Deirdre has stopped for a drink of water at a fountain in Fairmount Park.A man is sitting on the bench next to the fountain. He tells her that he once had a granddaughter about her age. He tells her that he loved her very much and that his granddaughter got hit by a car and she died.That is so sad, says Deirdre. She tells him that a car had hit Ginger, her cat. She died, too.The man nods, a tear forming in his eye. He says that, every year, on his granddaughter’s birthday, he comes to Fairmount Park, his granddaughter’s favorite place in the whole world.

The man begins to cry.

Deirdre drops the kickstand on her bike and walks to the bench. Just behind the bench there are thick bushes.

Deirdre offers the man a tissue . . .

Byrne sipped his coffee, lit a cigarette. His head pounded, the images

now fighting to get out. He had begun to pay a heavy price for them. Over the years he had medicated himself in many ways—legal and not, conventional and tribal. Nothing legal helped. He had seen a dozen doctors, heard all the diagnoses—to date, migraine with aura was the prevailing theory.

But there were no textbooks that described his auras. His auras were not bright, curved lines. He would have welcomed something like that.

His auras held monsters.

The first time he had seen the “vision” of Deirdre’s murder, he had not been able to fill in Gideon Pratt’s face. The killer’s face had been a blur, a watery draft of evil.

By the time Pratt had walked into Paradise, Byrne knew.

He popped a CD in the player, a homemade mix of classic blues. It was Jimmy Purify who had gotten him into the blues. The real thing, too: Elmore James, Otis Rush, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Bill Broonzy. You didn’t want to get Jimmy started on the Kenny Wayne Shepherds of the world.

At first Byrne didn’t know Son House from Maxwell House. But a lot of late nights at Warmdaddy’s and trips to Bubba Mac’s on the shore had taken care of that. Now, by the end of the second bar, third at the latest, he could tell the difference between Delta and Beale Street and Chicago and St. Louis and all the other shades of blue.

The first cut on the CD was Rosetta Crawford’s “My Man Jumped Salty on Me.”

If it was Jimmy who had given him the solace of the blues, it was Jimmy who had also brought him back into the light after the Morris Blanchard affair.

A year earlier, a wealthy young man named Morris Blanchard had murdered his parents in cold blood, blown them apart with a single shot each to the head from a Winchester 9410. Or so Byrne had believed, believed as deeply and completely as anything he had understood to be true in his two decades on the job.

He had interviewed the eighteen-year-old Morris five times, and each time the guilt had risen in the young man’s eyes like a violent sunrise.

Byrne had directed the CSU team repeatedly to comb Morris’s car, his dorm room, his clothing. They never found a single hair or fiber, nor a single drop of fluid that would place Morris in the room the moment his parents were torn apart by that shotgun.

Byrne knew that the only hope he’d had of getting a conviction was a confession. So he had pressed him. Hard. Every time Morris turned around, Byrne was there: concerts, coffee shops, studying in McCabe Library. Byrne had even sat through a noxious art house film called Eating, sitting two rows behind Morris and his date, just to keep the pressure on. The real police work that night had been staying awake during the movie.

One night Byrne parked outside Morris’s dorm room, just beneath the window on the Swarthmore campus. Every twenty minutes, for eight straight hours, Morris had parted the curtains to see if Byrne was still there. Byrne had made sure the window of the Taurus was open, and the glow of his cigarettes provided a beacon in the darkness. Morris made sure that every time he peeked he would offer his middle finger through the slightly parted curtains.

The game continued until dawn. Then, at about seven thirty that morning, instead of attending class, instead of running down the stairs and throwing himself on Byrne’s mercy, babbling a confession, Morris Blanchard decided to hang himself. He threw a length of towrope over a pipe in the basement of his dorm, stripped off all his clothes, then kicked out the sawhorse beneath him. One last fuck you to the system. Taped to his chest had been a note naming Kevin Byrne as his tormentor.

A week later the Blanchard’s gardener was found in a motel in Atlantic City, Robert Blanchard’s credit cards in his possession, bloody clothes stuffed into his duffel bag. He immediately confessed to the double homicide.

The door in Byrne’s mind had been locked.

For the first time in fifteen years, he had been wrong.

The cop-haters came out in full force. Morris’s sister Janice filed a wrongful death civil suit against Byrne, the department, the city. None of the litigation amounted to much, but the weight increased exponentially until it threatened to break him.

The newspapers had taken their shots at him, vilifying him for weeks with editorials and features. And while the Inquirer and Daily News and CityPaper had dragged him over the coals, they had eventually moved on. It was The Report—a yellow rag that fancied itself alternative press, but in reality was little more than a supermarket tabloid—and a particularly fragrant piece-of-shit columnist named Simon Close, who had made it personal beyond reason. For weeks after Morris Blanchard’s suicide, Simon Close wrote polemic after polemic about Byrne, the department, the police state in America, finally closing with a profile of the man Morris Blanchard would have become: a combination Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, and Jonas Salk, if one were to believe.

Before the Blanchard case, Byrne had given serious consideration to taking his twenty and heading to Myrtle Beach, maybe starting his own security firm like all the other burned-out cops whose will had been cracked by the savagery of inner-city life. He had done his time as interlocutor of the Bonehead Circus. But when he saw the pickets in front of the Roundhouse—including clever bons mots such as burn byrne!—he knew he couldn’t. He couldn’t go out like that. He had given far too much to the city to be remembered that way.

So he stayed.

And he waited.

There would be another case to take him back to the top.

Byrne drained his Irish, got comfortable in his seat. There was no reason to head home. He had a full tour ahead of him, starting in just a few hours. Besides, he was all but a ghost in his own apartment these days, a dull spirit haunting two empty rooms. There was no one there to miss him.

He looked at the windows of the police administration building, the amber glow of the ever-burning light of justice.

Gideon Pratt was in that building.

Byrne smiled, closed his eyes. He had his man, the lab would confirm it, and another stain would be washed from the sidewalks of Philadelphia.

Kevin Francis Byrne wasn’t a prince of the city.

He was king.

MONDAY, 5:15 A M

This is the other city, the one William Penn never envisioned when he surveyed his “green countrie town” between the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, dreaming of Greek columns and marble halls rising majestically from the pines.This is not the city of pride and history and vision, the place where the soul of a

great nation was created, but rather a part of North Philadelphia where living ghosts hover in darkness, hollow-eyed and craven.This is a low place, a place of soot and feces and ashes and blood, a place where men hide from the eyes of their children, and remit their dignity for a life of relentless sorrow. A place where young animals become old.

If there are slums in hell, they will surely look like this.

But in this hideous place, something beautiful will grow. A Gethsemane amid the cracked concrete and rotted wood and ruined dreams.

I cut the engine. It is quiet.

She sits next to me, motionless, as if suspended in this, the penultimate moment of her youth. In profile, she looks like a child. Her eyes are open, but she does not stir.

There is a time in adolescence when the little girl who once skipped and sang with abandon finally dispatches these ways with a claim on womanhood, a time when secrets are born, a body of clandestine knowledge never to be revealed. It happens at different times with different girls—sometimes at a mere twelve or thirteen, sometimes not until sixteen or older—but happen it does, in every culture, to every race. It is a time not heralded by the coming of the blood, as many believe, but rather by the awareness that the rest of the world, especially the male of the species, suddenly sees them differently.