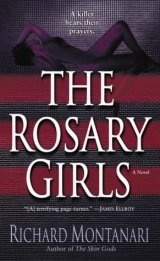

Текст книги "The Rosary Girls"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Маньяки

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

23

TUESDAY, 2:00 PM

“I really appreciate you coming in,” Byrne said to Brian Parkhurst. They were standing in the middle of the wide, semicircular room that housed the Homicide Unit.

“Anything I can do to help.” Parkhurst was dressed in a black-and-gray nylon jogging outfit and what looked like brand-new Reeboks. If he was at all nervous about being called in to talk to the police on this matter, it didn’t show. Then again, Jessica thought, he was a psychiatrist. If he could read anxiety, he could write composure. “Needless to say, we’re all devastated at Nazarene.”

“Are the students taking it hard?”

“I’m afraid so.”

The human traffic picked up around the two men. It was an old

trick—make the witness look for somewhere to sit down. The door to Interview Room A was wide open; all chairs in the common room were occupied. On purpose.

“Oh, I’m sorry.” Byrne’s voice was dripping with concern and sincerity. He was good, too. “Why don’t we sit in here?”

...

Brian Parkhurst sat in the upholstered chair across from Byrne in Interview Room A, the small, scruffy room where suspects and witnesses were questioned, made statements, provided information. Jessica observed through the two-way mirror. The door to the interview room remained open.

“Once again,” Byrne began, “we appreciate you taking the time.”

There were two chairs in the room. One was an upholstered desk chair; the other was a battered metal folding chair. Suspects never got the good chair. Witnesses did. Until they became suspects, that is.

“Not a problem,” Parkhurst said.

The murder of Nicole Taylor had led the noon news, with live breakins on all the local TV stations. Camera crews were at Bartram Gardens. Kevin Byrne had not asked Dr. Parkhurst if he had heard the news.

“Are you any closer to finding the person who killed Tessa?” Parkhurst asked in a practiced, conversational manner. It was the sort of tone he might use to start a therapy session with a new patient.

“We have a few leads,” Byrne said. “It’s still early in the investigation.”

“Great,” Parkhurst said. The word sounded cold and somewhat strident, given the nature of the crime.

Byrne let the word circle the room a few times, then float to the floor. He sat down opposite Parkhurst, dropped a file folder on the battered metal table. “I promise not to keep you too long,” he said.

“I have all the time you need.”

Byrne picked up the folder, crossed his legs. He opened the folder, carefully shielding the contents from Parkhurst. Jessica could see it was a 229, a basic biographical report. Nothing threatening to Brian Parkhurst, but he didn’t have to know that. “Tell me a little more about your work at Nazarene.”

“Well, it’s mostly consultation in the areas of learning and behavior,” Parkhurst said.

“You counsel students on their behavior?”

“Yes.”

“How so?”

“All children and adolescents face problems from time to time, Detective. They have fears about starting at a new school, they feel depressed, they quite often lack self-discipline or self-esteem, they lack social skills. As a result, they often experiment with drugs or alcohol, or think about suicide. I let my girls know that my door is always open to them.”

My girls, Jessica thought.

“Do the students you counsel find it easy to open up to you?”

“I like to think so,” Parkhurst said.

Byrne nodded. “What else can you tell me?”

Parkhurst continued. “Part of what we do is attempt to isolate potential learning difficulties in students, as well as design programs for those who may be at risk of failure. Things like that.”

“Are there a lot of students who fall into that category at Nazarene?” Byrne asked.

“Which category?”

“Students who are at a risk for failure.”

“No more than any other parochial high school, I would imagine,” Parkhurst said. “Probably fewer.”

“Why is that?”

“There is a legacy of high academic achievement at Nazarene,” he said.

Byrne scribbled a few notes. Jessica saw Parkhurst’s eyes roam the notepad.

Parkhurst added: “We also try to provide parents and teachers with the skills to cope with disruptive behavior, encourage tolerance, understanding, appreciation of diversity.”

This was strictly brochure copy, Jessica thought. Byrne knew it. Parkhurst knew it. Byrne shifted gears, making no attempt to mask it. “Are you a Catholic, Dr. Parkhurst?”

“Of course.”

“If you don’t mind me asking, why do you work for the archdiocese?”

“Excuse me?”

“I would imagine you could make a lot more money in private practice.”

Jessica knew that to be true. She had made a call to an old schoolmate who worked in personnel at the archdiocese. She knew exactly what Brian Parkhurst made. He earned $71,400 per year.

“The church is a very important part of my life, Detective. I owe it a great deal.”

“By the way, what’s your favorite William Blake painting?”

Parkhurst leaned back, as if trying to focus on Byrne more clearly. “My favorite William Blake painting?”

“Yeah,” Byrne said. “Me, I like Dante andVirgil at the Gates of Hell.”

“I, well, I can’t say I know very much about Blake.”

“Tell me about Tessa Wells.”

It was a gut shot. Jessica watched Parkhurst closely. He was smooth. Not a tic.

“What would you like to know?”

“Did she ever mention someone who might have been bothering her? Someone she might have been afraid of?”

Parkhurst seemed to think about this for a moment. Jessica wasn’t buying. Neither was Byrne.

“Not that I can recall,” Parkhurst said.

“Did she seem particularly troubled of late?”

“No,” Parkhurst said. “There was a period last year when I saw her a little more often than some of the other students.”

“Did you ever see her outside of school?”

Like right around Thanksgiving? Jessica wondered.

“No.”

“Were you a little closer to Tessa than some of the other students?” Byrne asked.

“Not really.”

“But there was some sort of bond.”

“Yes.”

“Is that how it all started with Karen Hillkirk?”

Parkhurst’s face reddened, then cooled instantly. He was clearly expecting this. Karen Hillkirk was the student with whom Parkhurst had had the affair in Ohio.

“It wasn’t what you think, Detective.”

“Enlighten us,” Byrne said.

On the word us, Parkhurst threw a glance at the mirror. Jessica thought she saw the slightest smile. She wanted to slap it off his face.

Parkhurst then lowered his head for a moment, penitent now, as if this was a story he had told many times, if only to himself.

“It was a mistake,” he began. “I...I was young myself. Karen was mature for her age. It just... happened.”

“Were you her counselor?”

“Yes,” Parkhurst said.

“So then you can see how there are those who would say that you abused a position of power, can’t you?”

“Of course,” Parkhurst said. “I understand that.”

“Did you have the same sort of relationship with Tessa Wells?”

“Absolutely not,” Parkhurst said.

“Are you acquainted with a Regina student named Nicole Taylor?”

Parkhurst hesitated for a second. The rhythm of the interview was starting to pick up in tempo. It appeared that Parkhurst was trying to slow it down. “Yes, I know Nicole.”

Know, Jessica thought. Present tense.

“You’ve counseled her?” Byrne asked.

“Yes,” Parkhurst said. “I work with the students at five diocesan schools.”

“How well do you know Nicole?” Byrne asked.

“I’ve seen her a few times.”

“What can you tell me about her?”

“Nicole has some self-image issues. Some...troubles at home,” Parkhurst said.

“What sort of self-image issues?”

“Nicole is a loner. She’s really into the whole Goth scene and that has somewhat isolated her at Regina.”

“Goth?”

“The Goth scene is loosely made up of kids who, for one reason or another, are spurned by the ‘normal’ kids. They tend to dress differently, listen to their own kinds of music.”

“Dress differently how?”

“Well, there are all kinds of Goth styles. The typical, or stereotypical Goth dresses in all black. Black fingernails, black lipstick, numerous piercings. But some kids dress in a Victorian manner, or an industrial style, if you will. They listen to everyone from Bauhaus to the old-school bands like the Cure and Siouxsie and the Banshees.”

Byrne just stared at Parkhurst for a few moments, fixing him in his chair. Parkhurst responded by rearranging his weight on the seat, straightening his clothes. He waited Byrne out. “You seem to know a lot about these things,” Byrne finally said.

“It’s my job, Detective,” Parkhurst said. “I can’t help my girls if I don’t know where they’re coming from.”

My girls again, Jessica noted.

“In fact,” Parkhurst continued, “I confess to owning a few Cure CDs myself.”

I’ll bet you do, Jessica mused.

“You mentioned Nicole had some troubles at home,” Byrne said. “What kind of troubles?”

“Well, for one, there is a history of alcohol abuse in her household,” Parkhurst said.

“Any violence?” Byrne asked.

Parkhurst paused. “Not that I recall. But even if I did, we’re getting into confidential matters here.”

“Is that the sort of thing students would necessarily share with you?”

“Yes,” Parkhurst said. “Those who are predisposed to do so.”

“Are many of the girls predisposed to discussing intimate details of their home lives with you?”

Byrne put a false emphasis on the word. Parkhurst caught it. “Yes. I like to think that I am good at putting young people at ease.”

Defensive now, Jessica thought.

“I don’t understand all these questions about Nicole. Has something happened to her?”

“She was found murdered this morning,” Byrne said.

“Oh my God.” Parkhurst’s face drained of color. “I saw the news...I had no...”

The news had not released the name of the victim.

“When was the last time you saw Nicole?”

Parkhurst thought for a few crucial moments. “It’s been a few weeks.”

“Where were you on Thursday and Friday mornings, Dr. Parkhurst?”

Jessica was certain that Parkhurst knew that the questioning had just crossed a barrier, the one that separated witness from suspect. He remained silent.

“It’s simply a routine question,” Byrne said. “We have to cover all bases.”

Before Parkhurst could answer, there was a soft rap on the open door.

It was Ike Buchanan.

“Detective?”

As they approached Buchanan’s office, Jessica could see a man standing with his back to the door. He was about five eleven, wearing a black overcoat, a dark fedora in his right hand. He was athletically built, wide-shouldered. His shaved head glistened beneath the fluorescents. They stepped into the office.

“Jessica, this is Monsignor Terry Pacek,” Buchanan said.

Terry Pacek, by reputation, was a fierce defender of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, a self-made man from the hardscrabble hills of Lackawanna County. Coal country. In an archdiocese where there were nearly one and a half million Catholics and close to three hundred parishes, no one was a more vocal or staunch advocate than Terry Pacek.

He had come into his own in 2002 during a brief sex scandal where six Philadelphia priests were dismissed, along with a few from Allentown. Granted, the scandal paled in comparison to what had taken place in Boston, but still, with its large Catholic population, Philadelphia reeled.

Terry Pacek had been front and center in the media during those few months, visiting every local talk show, every radio station, and showing up in every newspaper account. Jessica’s image of him, at the time, had been that of a well-spoken, well-educated pit bull. What she was not prepared for, now that she had met him in person, was the smile. At one moment, he looked like a compact version of a WWF wrestler ready to pounce. The next moment, his entire face changed, lighting up the room. She could see how he had charmed not only the media, but also the vicariate. She had the feeling that Terry Pacek could write his own future in the ranks of the church’s political hierarchy.

“Monsignor Pacek.” Jessica extended her hand.

“How is the investigation going?”

The question was directed at Jessica, but Byrne stepped forward. “It’s

still early,” Byrne said.

“I understand that there has been a task force formed?” Byrne knew that Pacek already knew the answer to this question. The

look on Byrne’s face told Jessica—and, perhaps, Pacek himself—that he didn’t appreciate it.

“Yes,” Byrne said. Flat, succinct, tepid.

“Sergeant Buchanan tells me that you have brought in Dr. Brian Parkhurst?”

Here we go, Jessica thought.

“Dr. Parkhurst volunteered to help us with the investigation. It turns out that he was acquainted with both victims.”

Terry Pacek nodded. “So Dr. Parkhurst is not a suspect?” “Absolutely not,” Byrne said. “He is here merely as a material witness.” For now, Jessica thought.

Jessica knew that Terry Pacek was walking a tightrope. On one hand, if someone was killing the Catholic schoolgirls of Philadelphia, he had an obligation to stay on top of the situation, making sure that the investigation was given a high priority.

On the other hand, he could not stand idly by and have archdiocese personnel brought in for questioning without counsel, or at least a show of support from the church.

“As spokesperson for the archdiocese, you can certainly understand my concern over these tragic events,” Pacek said. “The archbishop himself has communicated with me directly and authorized me to put all of the diocese’s resources at your disposal.”

“That’s very generous,” Byrne said.

Pacek handed Byrne a card. “If there is anything my office can do, please don’t hesitate to call us.”

“I sure will,” Byrne said. “Just out of curiosity, Monsignor, how did you know Dr. Parkhurst had come in?”

“He called my office after you called him.”

Byrne nodded. If Parkhurst gave the archdiocese a heads-up about a witness interview, it was pretty clear that he knew the conversation might turn into an interrogation.

Jessica glanced at Ike Buchanan. She saw him look over her shoulder and make a subtle move with his head, the sort of gesture you would make to tell someone that whatever they were looking for was in the room on the right.

Jessica followed Buchanan’s gaze into the common room, just outside Ike’s door, and found Nick Palladino and Eric Chavez there. They headed to Interview Room A, and Jessica knew what the nod meant.

Cut Brian Parkhurst loose.

TUESDAY, 3:20 PM

The main branch of the Free Library was the largest library in the city, located on Vine Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

Jessica sat in the fine arts section, poring over a huge collection of Christian art tomes, looking for something, anything, that resembled the tableaux they had uncovered at the two crime scenes, scenes to which they had no witnesses, no fingerprints, as well as two victims who, as far as they knew, were unrelated: Tessa Wells, sitting at the column in that filthy basement on North Eighth Street; Nicole Taylor reposing in the field of spring flowers.

With the assistance of one of the librarians, Jessica did a catalog search using various keywords. The results were overwhelming.

There were books on the iconography of the Virgin Mary, books on mysticism and the Catholic Church, books on relics, the Shroud of Turin, the Oxford Companion to Christian Art. There were countless guides to the Louvre, to the Uffizi, to the Tate. She skimmed books on the stigmata, on Roman history as it applied to crucifixion. There were pictorial Bibles, books on Franciscan, Jesuit, and Cistercian art, sacred heraldry, Byzantine icons. There were color plates of oil paintings, watercolors, acrylics, woodcuts, pen-and-ink drawings, murals, frescoes, sculptures in bronze, marble, wood, stone.

Where to begin?

When she found herself thumbing through a coffee table book on ecclesiastical embroidery, she knew she was getting a little off course. She tried keywords like prayer and rosary, and got hundreds of hits. She learned some basics, including that the rosary is Marian in nature, centered on the Virgin Mary, and is meant to be said while contemplating the face of Christ. She took as many notes as she could.

She checked out a few of the circulating books—many she had looked at were reference—and headed back to the Roundhouse, her mind reeling with religious imagery. Something in these books pointed to the inspiration for the madness of these crimes. She just had no idea how to ferret it out.

For the first time in her life she wished she had paid more attention in religion class.

TUESDAY, 3:30 PM

The blackness was complete, seamless, a perpetual night that ignored time. Beneath the darkness, very faint, was the sound of the world.

For Bethany Price, the veil of consciousness came and went like waves on the beach.

Cape May, she thought through the deep haze in her mind, the images fighting up from the depths of her memory. She hadn’t thought of Cape May in years. When she was small, her parents would take the family to Cape May, a few miles south of Atlantic City on the Jersey shore. She used to sit on the beach, her feet buried in the wet sand. Dad in his crazy Hawaiian trunks, Mom in her modest one-piece.

She remembered changing in the beach cabana, even then terribly self-conscious about her body, her weight. The thought made her touch herself. She was still fully clothed.

She knew she had ridden in a car for about fifteen minutes. It might have been longer. He had stuck her with a needle that had taken her to the grasp of sleep, but not quite into its arms. She had heard city sounds all around her. Buses, car horns, people walking and talking. She wanted to cry out to them, but she couldn’t.

It was quiet.

She was afraid.

The room was small, maybe five feet by three feet. Not a room at all, really. More like a closet. On the wall opposite the door she had felt a large crucifix. On the floor was a padded confessional kneeler. The carpeting on the floor was new; she smelled the petroleum scent of the new fiber. Beneath the door she could see a meager bar of yellow light. She was hungry and thirsty, but she dared not ask.

He wanted her to pray. He had stepped into the darkness and given her a rosary, and told her to begin with the Apostle’s Creed. He hadn’t touched her in a sexual way. Not that she knew of, anyway.

He had left for a while, but was now back. He was pacing outside the closet, upset about something it seemed.

“I can’t hear you,” he said from the other side of the door. “What did Pope Pius the Sixth say about this?”

“I...I don’t know,” Bethany said.

“He said that, without contemplation, the rosary is a body without a soul, and its recitation runs the risk of becoming a mechanical repetition of formulas, in violation of the admonition of Christ.”

“I’m sorry.”

Why was he doing this? He had been nice to her before. She had gotten into trouble and he had treated her with respect.

The sound of the machine grew louder.

It sounded like a drill.

“Now!” boomed the voice.

“Hail Mary full of grace, the Lord is with thee,” she began for what was probably the hundredth time.

The Lord is with thee, she thought, her mind beginning to fog again.

Is the Lord with me?

TUESDAY, 4:00 PM

The black-and-white videotape was grainy, but clear enough to see the comings and goings through the parking lot at St. Joseph’s Hospital. The traffic—both automotive and pedestrian—was what one would expect: ambulances, police cars, delivery vans from medical and

maintenance supply houses. A majority of the personnel were hospital employees: doctors, nurses, orderlies, housekeeping. Through this entrance came a few visitors, a handful of police officers.

Jessica, Byrne, Tony Park, and Nick Palladino were jammed into the small room that doubled as a snack room and video room.At the 4:06:03 point of the tape, they saw Nicole Taylor.

Nicole walks out of the door marked special hospital services, hesitates for a few moments, then ambles slowly toward the street. She has a small purse on a strap over her right shoulder and what looks like a bottle of juice or perhaps a Snapple in her left hand. There was no purse or bottle found at the crime scene in Bartram Gardens.

At the street, Nicole seems to notice something at the top of the frame. She covers her mouth, perhaps in surprise, then walks over to a car parked at the very left edge of the screen. It appears to be a Ford Windstar. No occupant of the car is visible.

Just as Nicole reaches the passenger side of the car, a delivery truck from Allied Medical pulls between the camera and the minivan.

“Shit,” Byrne said. Come on, come on...”

The time on the tape is 4:06:55.

The driver of the Allied Medical truck gets out of the driver’s side and heads into the hospital.A few minutes later he returns, enters the cab.

When the truck pulls away, the Windstar and Nicole are gone.

They let the tape run for five more minutes, then fast-forwarded. Neither Nicole nor the Windstar returned.

“Can you rewind it to the point where she walks up to the van?” Jessica asked.

“No problem,” Tony Park said.

They watched the tape over and over again. Nicole leaving the building, walking beneath the canopy, approaching the Windstar, each time freezing it at the moment the truck pulls up and obscures them.

“Can you get us in closer?” Jessica asked.

“Not on this machine,” Park replied. “The lab can do all kinds of tricks, though.”

The AV Unit, located in the basement of the Roundhouse, was capable of all kinds of video enhancement. The tape they were watching had been dubbed from the original, due to the fact that surveillance tape is recorded at a very slow speed, rendering it impossible to play on a normal VCR.

Jessica leaned close to the small black-and-white monitor. It appeared that the Windstar’s license plate was Pennsylvania issue, ending in 6. It was impossible to tell what numbers, letters, or combinations thereof preceded this. If they had the beginning numbers on the plate, it would make it a lot easier to match the plate with the make and model of the car.

“Why don’t we try to cross-reference Windstars with that number?” Byrne asked. Tony Park turned to walk from the room. Byrne stopped him, wrote something on his pad, tore it off, and handed it to Park. With that, Park was out the door.

The remaining detectives continued to watch the tape as traffic came and went; as personnel walked lazily toward their jobs or spryly away. Jessica found it excruciating to know that, behind the truck obscuring her view of the Windstar, Nicole Taylor was quite likely talking to someone who would soon end her life.

They watched the tape another six times, failing to glean any new information.

Tony Park returned with a thick stack of computer printouts in hand. Ike Buchanan followed.

“There are twenty-five hundred Windstars registered in Pennsylvania,” Park said. “Two hundred or so end in the number six.”

“Shit,” Jessica said.

He then held up the printout, beaming. One of the lines was highlighted in bright yellow. “One of them is registered to Dr. Brian Allan Parkhurst of Larchwood Street.”

Byrne was on his feet in an instant. He glanced at Jessica. He ran a finger over the scar on his forehead.

“It’s not enough,” Buchanan said.

“Why not?” Byrne asked.

“Where do you want me to start?”

“He knew both victims, and we can put him at the scene where Nicole Taylor was last seen—”

“We don’t know that it was him. We don’t know that she even got in that car.”

“He had opportunity,” Byrne plowed ahead. “Maybe even motive.”

“Motive?” Buchanan asked.

“Karen Hillkirk,” Byrne said.

“He didn’t kill Karen Hillkirk.”

“He didn’t have to. Tessa Wells was underage. Maybe she was going to go public with their affair.”

“What affair?”

Buchanan was, of course, right.

“Look, he’s an MD,” Byrne said, selling hard. Jessica got the sense that even Byrne was not convinced that Parkhurst was their doer. But Parkhurst knew something. “The ME’s report said both girls were subdued with midazolam and then given a paralytic drug by injection. He drives a minivan, which is also right on. He fits the profile. Let me put him back in the chair. Twenty minutes. If he doesn’t tip, we cut him loose.”

Ike Buchanan briefly considered the idea. “If Brian Parkhurst sets foot in this building again, he’s coming in with a lawyer from the archdiocese. You know it, and I know it,” Buchanan said. “Let’s do a little more legwork before we connect these dots. Let’s find out if that Windstar belongs to an employee of the hospital before we start hauling people in. Let’s see if we can account for every minute of Parkhurst’s day.”

Most police work is mind– and ass-numbingly dull. Much of the time is spent at a wobbly gray desk with sticky drawers full of paper, a phone in one hand, cold coffee in the other. Calling people. Calling people back. Waiting for people to call you back. Hitting dead ends, roaring up blind alleys, walking dejectedly out. People interviewed saw no evil, heard no evil, spoke no evil—only to discover that they remember a key fact two weeks later. Detectives talk to funeral parlors to see if they had a procession on the street that day. They talk to newspaper deliverymen, school crossing guards, landscapers, painters, city workers, street cleaners. They talk to junkies, hookers, alkies, dealers, panhandlers, vendors, anyone who makes a habit or vocation of simply hanging around the corner in which they are interested.

And then, after all the phone calls prove worthless, the detectives get to drive around the city, asking the same questions to the same people in person.

By midafternoon, the investigation had settled into a lethargic drone, like the seventh-inning dugout of a team down 5–0. Pencils tapped, phones stood mute, eye contact was avoided. The task force, with the help of a handful of uniformed officers, had managed to contact all but a handful of the Windstar owners. Two of them worked at St. Joseph’s, one of them in housekeeping.

At five o’clock they held a press conference behind the Roundhouse. The police commissioner and the district attorney were front and center. All the expected questions were asked. All the expected answers were given. Kevin Byrne and Jessica Balzano were on camera and identified to the media as leading the task force. Jessica was hoping she wouldn’t have to speak on camera. She didn’t.

By five twenty they were back at their desks. They flipped through the local channels until they found a replay of the press conference. Brief applause, hoots, and hollers greeted the close-up of Kevin Byrne. A local anchor’s voiceover accompanied the footage of Brian Parkhurst’s exit from the Roundhouse earlier in the day. Parkhurst’s name was plastered on the screen beneath the slow-motion image of him getting into his car.

Nazarene Academy had called back with the information that Brian Parkhurst had left early the previous Thursday and Friday, and that he had arrived at the school no earlier than 8:15 am on Monday. He would have had ample time to abduct both girls, dump both bodies, and still maintain his schedule.

At five thirty, just after Jessica received a call back from the Denver Board of Education, effectively eliminating Tessa’s old boyfriend Sean Brennan from the suspect pool, she and John Shepherd drove down to the forensic lab, the new state-of-the-art facility just a few blocks from the Roundhouse at Eighth and Poplar. There was new information. The bone found in Nicole Taylor’s hands was a section cut from a leg of lamb. It appeared to have been cut with a serrated blade and sharpened on an oilstone.

So far their victims had been found holding a sheep bone and a reproduction of a William Blake painting. The information, although helpful, shed no light into any corner of the investigation.

“We’ve also got matching carpet fibers from both victims,” Tracy McGovern said. Tracy was the deputy director of the lab.

All across the room, fists clenched, pumping the air. They had evidence. Synthetic fibers could be traced.

“Both girls had the same nylon fibers along the hem of their skirts,” Tracy said. “Tessa Wells had more than a dozen. Nicole Taylor’s skirt yielded only a few, due to the fact that she had been out in the rain, but they were there.”

“Is it residential? Commercial? Automotive?” Jessica asked.

“Probably not automotive. I’d say midrange residential carpeting. Dark blue. But the pattern of the fibers was spread out along the very bottom of the hem. It wasn’t anywhere else on their clothing.”

“So they weren’t lying down on the carpet?” Byrne asked. “Or sitting on it?”

“No,” Tracy said. “For this kind of pattern, I’d say they were—”

“Kneeling,” Jessica said.

“Kneeling,” Tracy echoed.

At six o’clock Jessica sat at a desk, spinning a cup of cold coffee, thumbing through her books on Christian art. There were some promising leads, but nothing that duplicated the postures of the victims at the crime scenes.

Eric Chavez had a dinner date. He stood in front of the small two-way mirror in Interview Room A, tying and retying his tie, searching for the perfect double Windsor. Nick Palladino was finishing up the calls to the remaining few Windstar owners.

Kevin Byrne stared at the wall of photographs like Easter Island statuary. He seemed rapt, consumed by the minutiae, replaying the time line over and over in his mind. Images of Tessa Wells, images of Nicole Taylor, snapshots of the death house on Eighth Street, pictures of the daffodil garden at Bartram. Hands, feet, eyes, arms, legs. Pictures with rulers to provide scale. Pictures with grids to provide context.

The answers to all Byrne’s questions were directly in front of him, and to Jessica he looked like a man in a catatonic state. She would have given a month’s salary to be privy to Kevin Byrne’s private thoughts at that moment.

Late afternoon slogged toward evening. And yet Kevin Byrne stood motionless, scanning the board, left to right, top to bottom.

Suddenly he removed a close-up photograph of Nicole Taylor’s left palm. He took it over to the window and held it up to the graying light. He looked at Jessica, but it appeared he was looking right through her. She was just an object in the path of his thousand-yard stare. He removed a magnifying glass from a desk and turned back to the photo.

“Christ,” he finally said, drawing the attention of the handful of detectives in the room. “I can’t believe we didn’t see it.”