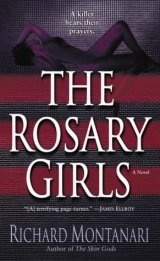

Текст книги "The Rosary Girls"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Маньяки

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

And, from that moment on, the balance of power shifts, and is never the same.

No, she is no longer a virgin, but she will be a virgin once again.At the pillar there will be a scourge and from this blight will come resurrection.

I exit the vehicle and look east and west. We are alone. The night air is chilled, even though the days have been unseasonably warm.

I open the passenger door and take her hand in mine. Not a woman, nor a child. Certainly not an angel.Angels do not have free will.

But a calm-shattering beauty nonetheless.

Her name is Tessa Ann Wells.

Her name is Magdalene.

She is the second.

She will not be the last.

MONDAY, 5:20 A M

Dark.

A breeze brought exhaust fumes and something else. A paint smell. Kerosene, maybe. Beneath it, garbage and human sweat. A cat shrieked, then—

Quiet.

He was carrying her down a deserted street.

She could not scream. She could not move. He had injected her with

a drug that made her limbs feel leaden and frail; her mind, thick with a gauzy gray fog.

For Tessa Wells, the world passed by in a churning rush of muted colors and glimpsed geometric shapes.

Time stalled. Froze. She opened her eyes.

They were inside. Descending wooden steps. The smell of urine and rotting lunch meat. She hadn’t eaten in a long time and the smell made her stomach lurch and a trickle of bile rise in her throat.

He placed her at the foot of a column, arranging her body and limbs as if she were some sort of doll.

He put something in her hands.

The rosary.

Time passed. Her mind swam away again. She opened her eyes once more as he touched her forehead. She could sense the cruciform shape he inscribed there.

My God, is he anointing me?

Suddenly, memories shimmered silver in her mind, a mercurial reflection of her childhood. She recalled—

—horseback riding in Chester County and the way the wind would sting my face and Christmas morning and the way Mom’s crystal captured the colored lights from the enormous tree Dad bought every year and Bing Crosby and that silly song about Hawaiian Christmas and its—

He stood in front of her, now, threading a huge needle. He spoke in a slow monotone—

Latin?

—as he tied a knot in the thick black thread and pulled it tight.

She knew she would not leave this place.

Who would take care of her father?

Holy Mary, mother of God . . .

He had made her pray in that small room for a long time. He had whispered the most horrible words in her ear. She had prayed for it to end.

Pray for us sinners . . .

He pushed her skirt up her thighs, then all the way to her waist. He dropped to his knees, spread her legs. The lower half of her body was completely paralyzed.

Please God, make it stop.

Now...

Make it stop.

And at the hour of our death . . .

Then, in this damp and decaying place, this earthly hell, she saw the steel drill bit glimmer, heard the whir of the motor, and knew her prayers were finally answered.

MONDAY, 6:50 A M

“Cocoa Puffs.”

The man glared at her, his mouth set in a tight yellow rictus. He was standing a few feet away, but Jessica could feel the danger radiate from him, could suddenly smell the bitter tang of her own terror.

As he held her in his unwavering stare, Jessica sensed the edge of the roof approaching behind her. She reached for her shoulder holster but, of course, it was empty. She rummaged her pockets. Left side: something that felt like a barrette, along with a pair of quarters. Right side: air. Great. On her way down she would be fully equipped to put her hair up and make a long-distance call.

Jessica decided to employ the one bludgeon she had used her entire life, the one fearsome device that had managed to get her into, and out of, most of her troubles. Her words. But instead of anything remotely clever or threatening, all she could manage was a wobbly:

“What?”

Again, the thug said: “Cocoa Puffs.”

The words seemed as incongruous as the setting: a dazzlingly bright day, a cloudless sky, white gulls forming a lazy ellipse overhead. It felt like it should be Sunday morning, but Jessica somehow knew it wasn’t. No Sunday morning could shoulder this much peril, nor conjure this much fear. No Sunday morning would find her on top of the Criminal Justice Center in downtown Philadelphia, with this terrifying gangster moving toward her.

Before Jessica could speak, the gang member repeated himself one last time. “I made you Cocoa Puffs, Mommy.”

Hello.

Mommy?

Jessica slowly opened her eyes. Morning sunlight burrowed in from everywhere, slim yellow daggers that poked at her brain. It wasn’t a gangster at all. It was, instead, her three-year-old daughter Sophie, perched on her chest, her powder-blue nightie deepening the ruby glow of her cheeks, her face a soft pink eye in a hurricane of chestnut curls. Now, of course, it all made sense. Now Jessica understood the weight on her heart, and why the gruesome man in her nightmare had sounded a little bit like Elmo.

“Cocoa Puffs, honey?”

Sophie Balzano nodded.

“What about Cocoa Puffs?”

“I made you breakfess, Mommy.”

“You did?”

“Uh-huh.”

“All by yourself?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Aren’t you a big girl.”

“I am.”

Jessica offered her sternest expression. “What did Mommy say about climbing on the cabinets?”

Sophie’s face went into a series of evasive maneuvers, attempting to conceive a story that might explain how she got the cereal out of the upper cabinets without climbing on the countertops. In the end, she just gave her mother a flash of the big browns and, as always, the discussion was over.

Jessica had to smile. She envisioned the Hiroshima that must be the kitchen. “Why did you make me breakfast?”

Sophie rolled her eyes. Wasn’t it obvious? “You need breakfess on your first day of school!”

“That’s true.”

“It’s the most ’portant meal of the day!”

Sophie was, of course, far too young to grasp the concept of work. Ever since her first foray into preschool—a pricey Center City facility called Educare—whenever her mother left the house for any extended period of time, for Sophie, it was going to school.

As morning toed the threshold of consciousness, the fear began to melt away. Jessica wasn’t being held at bay by a criminal, a dreamscenario that had become all too familiar to her in the previous few months. She was in the arms of her beautiful baby. She was in her heavily mortgaged twin in Northeast Philadelphia; her heavily financed Jeep Cherokee was in the garage.

Safe.

Jessica reached over and clicked on the radio as Sophie gave her a big hug and a bigger kiss. “It’s getting late!” Sophie said, then slid off the bed and rocketed across the bedroom. “C’mon, Mommy!”

As Jessica watched her daughter disappear around the corner, she thought that, in her twenty-nine years, she had never been quite so grateful to greet the day; never so glad to be over the nightmare she began having the day she heard she would be moving to the Homicide Unit.

Today was her first day as a murder cop.

She hoped it would be the last day she had the dream.

Somehow, she doubted it.

Detective.

Even though she had spent nearly three years in the Auto Unit, and had carried a badge the entire time, she knew that it was the more select units of the department—Robbery, Narcotics, and Homicide—that carried the true prestige of that title.

As of today, she was one of the elite. One of the chosen. Of all the gold-badge detectives on the Philadelphia police force, those men and women in the Homicide Unit were looked upon as gods.You could aspire to no more lofty a law enforcement calling. While it was true that dead bodies showed up in the course of every kind of investigation, from robberies and burglaries, to drug deals gone bad, to domestic arguments that got out of hand, whenever a pulse could not be found, the divisional detectives picked up the phone and called Homicide.

As of today, she would speak for those who could no longer speak for themselves.

Detective.

“You want some of Mommy’s cereal?” Jessica asked. She was halfway through her huge bowl of Cocoa Puffs—Sophie had poured her nearly the entire box—which was rapidly turning into a sort of sugary, beige stucco.

“No sankoo,” Sophie said through a mouthful of cookie.

Sophie was sitting across from her at the kitchen table, vigorously coloring what appeared to be an orange, six-legged version of Shrek, making roundabout work of a hazelnut biscotti, her favorite.

“You sure?” Jessica asked. “It’s really, really good.”

“No sankoo.”

Damn, Jessica thought. The kid was as stubborn as she was. Whenever Sophie made up her mind about something, she was immovable. This, of course, was good news and bad news. Good news, because it meant that Jessica and Vincent Balzano’s little girl didn’t give up easily. Bad news, because Jessica could envision arguments with the teenaged Sophie Balzano that would make Desert Storm look like a sandbox fracas.

But now that she and Vincent were separated, Jessica wondered how it would affect Sophie in the long term. It was painfully clear that Sophie missed her daddy.

Jessica looked at the head of the table, where Sophie had set a place for Vincent. Granted, the silverware she selected was a small soup ladle and a fondue fork, but it was the effort that mattered. Over the past few months, whenever Sophie went about anything that involved a family setting—including her Saturday-afternoon tea parties in the backyard, soirees generally attended by her menagerie of stuffed bears, ducks, and giraffes—she had always set a place for her father. Sophie was old enough to know that the universe of her small family was upside down, but young enough to believe that little-girl magic just might make it better. It was one of the thousand reasons Jessica’s heart ached every day.

Jessica was just starting to formulate a plan for distracting Sophie so she could get to the sink with her salad bowl full of Cocoa muck when the phone rang. It was Jessica’s first cousin Angela.Angela Giovanni was a year younger, and was the closest thing to a sister Jessica had ever had. “Hey, Homicide Detective Balzano,” Angela said.

“Hey, Angie.”

“Did you sleep?”

“Oh yeah. I got the full two hours.”

“You ready for the big day?”

“Not really.”

“Just wear your tailored armor, you’ll be fine,” Angela said. “If you say so,” Jessica said. “It’s just that...”

“What?”

Jessica’s dread was so unfocused, so general in nature, she had a hard

time putting a name to it. It really did feel like her first day of school. Kindergarten. “It’s just that this is the first thing in my life I’ve ever been afraid of.”

“Hey!” Angela began, revving up her optimism. “Who made it through college in three years?”

It was an old routine for the two of them, but Jessica didn’t mind. Not today. “Me.”

“Who passed the promotion exam on her first try?”

“Me.”

“And who kicked the living, screaming shit out of Ronnie Anselmo for copping a feel during Beetlejuice?”

“That would be me,” Jessica said, even though she remembered not really minding all that much. Ronnie Anselmo was pretty cute. Still, there was a principle.

“Damn straight. Our own little Calista Braveheart,”Angela said. “And remember what Grandma used to say: Meglio un uovo oggi che una gallina domani.”

Jessica flashed on her childhood, on holidays at her grandmother’s house on Christian Street in South Philly, on the aromas of garlic and basil and Asiago and roasting peppers. She recalled the way her grandmother would sit on her tiny front stoop in spring and summer, knitting needles in hand, the seemingly endless afghan spooling on the spotless cement, always green and white, the colors of the Philadelphia Eagles, spouting her witticisms to all who would listen. This one she used all the time. Better an egg today than a chicken tomorrow.

The conversation settled into a tennis match of family inquiries. Everyone was fine, more or less. Then, as expected, Angela said:

“You know, he’s been asking about you.”

Jessica knew exactly who Angela meant by he.

“Oh yeah?”

Patrick Farrell was an emergency room physician at St. Joseph’s Hospital, where Angela worked as an RN. Patrick and Jessica had had a brief, if rather chaste affair before Jessica had gotten engaged to Vincent. She had met him one night when, as a uniformed cop, she brought a neighborhood boy into the ER, a kid who had blown off two fingers with an M-80. She and Patrick had casually dated for about a month.

Jessica was seeing Vincent at the time—himself a uniformed officer out of the Third District. When Vincent popped the question, and Patrick was faced with a commitment, Patrick had deferred. Now, with the separation, Jessica had asked herself somewhere in the neighborhood of a billion times if she had let the good one get away.

“He’s pining, Jess,” Angela said. Angela was the only person north of Mayberry who used words like pining. “Nothing more heartbreaking than a beautiful man in love.”

She was certainly right about the beautiful part. Patrick was that rare black Irish breed—dark hair, dark blue eyes, broad shoulders, dimples. Nobody ever looked better in a white lab coat.

“I’m a married woman, Angie.”

“Not that married.”

“Just tell him I said... hello,” Jessica said.

“Just hello?”

“Yeah. For now. The last thing I need in my life right now is a man.”

“Probably the saddest words I’ve ever heard,” Angela said.

Jessica laughed. “You’re right. It does sound pretty pathetic.”

“Everything all set for tonight?”

“Oh yeah,” Jessica said.

“What’s her name?”

“You ready?”

“Hit me.”

“Sparkle Munoz.”

“Wow,” Angela said. “Sparkle?”

“Sparkle.”

“What do you know about her?”

“I saw a tape of her last fight,” Jessica said. “Powder puff.”

Jessica was one of a small but growing coterie of Philly female boxers. What began as a lark at Police Athletic League gyms, while Jessica tried to lose the weight she had gained during her pregnancy, had grown into a serious pursuit. With a record of 3–0, all three wins by knockout, Jessica was already starting to get some good press. The fact that she wore dusty rose satin trunks with the words jessie balls stitched across the waistband didn’t hurt her image, either.

“You’re gonna be there, right?” Jessica asked.

“Absolutely.”

“Thanks, cuz,” Jessica said, glancing at the clock. “Listen, I gotta run.”

“Me, too.”

“Got one more question for you, Angie.”

“Shoot.”

“Why did I become a cop again?”

“That’s easy,” Angela said. “To molest and swerve.”

“Eight o’clock.”

“I’ll be there.”

“Love you.”

“Love you back.”

Jessica hung up the phone, looked at Sophie. Sophie had decided it was a good idea to connect the dots on her polka-dot dress with an orange Magic Marker.

How the hell was she going to get through this day?

With Sophie changed and deposited at Paula Farinacci’s—the godsend babysitter who lived three doors down, and one of Jessica’s best friends—Jessica walked back home, her maize-colored suit already starting to wrinkle. When she had been in Auto, she could opt for jeans and leather, T-shirts and sweatshirts, the occasional pantsuit. She liked the look of the Glock on the hip of her best faded Levi’s. All cops did, if they were being honest. But now she had to look a little more professional.

Lexington Park was a stable section of Northeast Philadelphia that bordered Pennypack Park. It was also home to a lot of law enforcement types, and for that reason, there were not a lot of burglaries in Lexington Park these days. Second-story men seemed to have a pathological aversion to hollow points and slavering rottweilers.

Welcome to Cop Land.

Enter at your own risk.

Before Jessica reached her driveway, she heard the metallic growl and knew it was Vincent. Three years in Auto gave her a highly attuned logic when it came to engines, so when Vincent’s throaty 1969 Shovelhead Harley rounded the corner and roared to a stop in the driveway, she knew her piston-sense was still fully functioning. Vincent also had an old Dodge van, but, like most bikers, the minute the thermometer topped forty degrees—and often before—he was on his Hog.

As a plainclothes narcotics detective, Vincent Balzano had an unfettered leeway when it came to his appearance. With his four-day beard, scuffed leather jacket, and Serengeti sunglasses, he looked a lot more like a perp than a cop. His dark brown hair was longer than she’d ever seen it. It was pulled back into a ponytail. The ever-present gold crucifix he wore on a gold chain around his neck winked in the morning sunlight.

Jessica was, and always had been, a sucker for the bad-boy, swarthy type.

She banished that thought and put on her game face.

“What do you want, Vincent?”

He took off his sunglasses and calmly asked: “What time did he leave?”

“I don’t have time for this shit.”

“It’s a simple question, Jessie.”

“It’s also none of your business.”

Jessica could see that this hurt but, at the moment, she didn’t care.

“You are my wife,” he began, as if giving her a primer on their life. “This is my house. My daughter sleeps here. It is my fucking business.”

Save me from the Italian-American male, Jessica thought. Was there a more possessive creature in all of nature? Italian-American men made silverback gorillas look reasonable. Italian-American cops were even worse. Like herself, Vincent was born and bred on the streets of South Philly.

“Oh, now it’s your business? Was it your business when you were banging that putana? Huh? When you were banging that big-ass South Jersey frosted skank in my bed?”

Vincent rubbed his face. His eyes were red, his posture a little weary. It was clear he was coming off a long tour. Or maybe a long night doing something else. “How many times do I have to apologize, Jess?”

“A few million more, Vincent. Then we’ll be too friggin’ old to remember how you cheated on me.”

Every unit has its badge bunnies, cop groupies who saw a uniform or a badge and suddenly had the uncontrollable urge to flop onto their backs and spread their legs. Narcotics and Vice had the most, for all the obvious reasons. But Michelle Brown was no badge bunny. Michelle Brown was an affair. Michelle Brown had fucked her husband in her house.

“Jessie.”

“I need this shit today, right? I really need this.”

Vincent’s face softened, as if he’d just remembered what day this was. He opened his mouth to speak, but Jessica raised a hand, cutting him off.

“Don’t,” she said. “Not today.”

“When?”

The truth was, she didn’t know. Did she miss him? Desperately. Would she show it? Never in a million years.

“I don’t know.”

For all his faults—and they were legion—Vincent Balzano knew when to quit with his wife. “C’mon,” he said. “Let me give you a ride, at least.”

He knew she would refuse, opting out of the Phyllis Diller look a ride to the Roundhouse on a Harley would provide for her.

But he smiled that damn smile, the one that got her into bed in the first place, and she almost—almost—caved.

“I’ve got to go, Vincent,” she said.

She walked around the bike and continued on toward the garage. As tempted as she was to turn around, she resisted. He had cheated on her and now she was the one who felt like shit.

What’s wrong with this picture?

While she deliberately fumbled with the keys, drawing it out, she eventually heard the bike start, back up, roar defiantly, and disappear up the street.

When she started the Cherokee, she punched 1060 on the dial. KYW told her that I-95 was jammed. She glanced at the clock. She had time. She’d take Frankford Avenue into town.

As she pulled out of the drive, she saw an EMS van in front of the Arrabiata house across the street. Again. She made eye contact with Lily Arrabiata, and Lily waved. It seemed Carmine Arrabiata was having his weekly false-alarm heart attack, a regular event for as far back as Jessica could remember. It had gotten to the point that the city would no longer send an EMS rescue. The Arrabiatas had to call private ambulances. Lily’s wave was twofold. One, to say good morning. The other to tell Jessica that Carmine was fine. At least for the next week or so.

Heading toward Cottman Avenue, Jessica thought about the stupid fight she had just had with Vincent, and how a simple answer to his initial question would’ve ended the discussion immediately. The night before she had attended a Catholic Food Drive organizational meeting with an old friend of the family, little Davey Pizzino, all five foot one of him. It was a yearly occasion Jessica had attended since she was a teenager, and the farthest thing imaginable from a date, but Vincent didn’t need to know that. Davey Pizzino blushed at Summer’s Eve commercials. Davey Pizzino, at thirty-eight, was the oldest living virgin east of the Alleghenies. Davey Pizzino left at nine thirty.

But the fact that Vincent had probably spied on her pissed her off to no end.

Let him think what he wanted.

On the way into Center City, Jessica watched the neighborhoods change. No other city she could think of had a personality so split between blight and splendor. No other city clung to the past with more pride, nor demanded the future with more fervor.

She saw a pair of brave joggers working their way up Frankford, and the floodgates opened wide.A torrent of memories and emotions washed over her.

She had begun running with her brother when he was seventeen; she, just a gangly thirteen, loosely constructed of pointy elbows, sharp shoulder blades, and bony kneecaps. For the first year or so she hadn’t a prayer of matching either his pace or his stride. Michael Giovanni stood just under six feet and weighed a trim and muscular 180.

In the summer heat, the spring rain, the winter snow they would jog through the streets of South Philly; Michael, always a few steps ahead; Jessica, always struggling to keep up, always in silent awe of his grace. She had beaten him to the steps of St. Paul’s once, on her fourteenth birthday, a contest to which Michael had never wavered in his claim of defeat. She knew he had let her win.

Jessica and Michael had lost their mother to breast cancer when Jessica was only five, and from that day forward Michael had been there for every scraped knee, every young girl’s heartbreak, every time she had been victimized by some neighborhood bully.

She had been fifteen when Michael had joined the Marine Corps, following in their father’s footsteps. She recalled how proud they had all been when he came home in his dress uniform for the first time. Every one of Jessica’s girlfriends had been desperately in love with Michael Giovanni, his caramel eyes and easy smile, the confident way he could put old people and children at ease. Everyone knew he would join the police force after his tour of duty, also following in their father’s footsteps.

She had been fifteen when Michael, serving in the First Battalion, Eleventh Marines, was killed in Kuwait.

Her father, a thrice-decorated veteran of the police force, a man who still carried his late wife’s internment card in his breast pocket, had closed his heart completely that day, a terrain he now tread only in the company of his granddaughter. Although small of stature, Peter Giovanni had stood ten feet tall in the company of his son.

Jessica had been headed to prelaw, then law school, but on the night they received word of Michael’s death she knew that she would join the police force.

And now, as she began what was essentially an entirely new career in one of the most respected homicide units of any police department in the country, it looked like law school was a dream relegated to the realm of fantasy.

Maybe one day.

Maybe.

By the time Jessica pulled into the parking lot at the Roundhouse, she realized that she didn’t recall any of it. Not a single thing. All the cramming in procedure, evidence, the years on the street, everything evacuated her brain.

Did the building get bigger? she wondered.

At the door she caught her reflection in the glass. She was wearing a fairly expensive skirt suit, her best sensible girl-cop shoes. A big difference from the torn jeans and sweatshirts she had favored as an undergrad at Temple, in those giddy years before Vincent, before Sophie, before the academy, before all... this. Not a care in the world, she thought. Now her world was built on worry, framed with concern, with a leaky roof shingled with trepidation.

Although she had entered this building many times, and although she could probably find her way to the bank of elevators blindfolded, it all seemed foreign to her, as if she were seeing it for the first time. The sights, the sounds, the smells all blended into the demented carnival that was this small corner of the Philadelphia justice system.

It was her brother Michael’s beautiful face that Jessica saw as she grabbed the handle on the door, an image that would come back to her many times over the next few weeks as the things upon which she had based her whole life became redefined as madness.

Jessica opened the door, stepped inside, thinking:

Watch my back, big brother.

Watch my back.