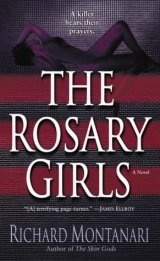

Текст книги "The Rosary Girls"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Маньяки

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

52

WEDNESDAY, 4:15 PM

She is summer, this one. She is water.

Her white-blond hair is long, pulled back into a ponytail, fastened with an amber cat’s-eye bolo. It reaches the middle of her back in a glistening waterfall. She wears a faded denim skirt and a burgundy wool sweater. She

carries a leather jacket over her arm. She has just emerged from the Barnes & Noble at Rittenhouse Square, where she works part time.

She is still quite thin, but it looks like she has put on weight since the last time I saw her.

Good for her.

The street is crowded, so I am sporting a ball cap and sunglasses. I walk right up to her.

“Remember me?” I ask, lifting the sunglasses momentarily.

At first, she is not sure. I am older, so I belong to that world of adults who could, and usually do, mean authority.As in—the end of the party.After a few seconds, recognition alights.

“Sure!” she says, her face brightening.

“Your name is Kristi, right?”

She blushes.“Yep.You have a good memory!”

“How have you been feeling?”

The blush deepens, morphing from the demure demeanor of a confident young woman to the embarrassment of a little girl, her eyes ringed with shame. “I’m, you know, a lot better now,” she says.“That was—”

“Hey,” I say, holding up a hand, stopping her.“There’s nothing for you to be ashamed of. Not one single thing. I could tell you stories, believe me.”

“Really?”

“Absolutely,” I say.

We walk down Walnut Street. Her posture changes slightly. A little selfconscious now.

“So, what are you reading?” I ask, pointing to the bag she carries.

She blushes again.“I’m embarrassed.”

I stop walking. She stops with me.“Now, what did I just tell you?”

Kristi laughs.At this age, it is always Christmas, always Halloween, always the Fourth. Every day is the day.“Okay, okay,” she concedes. She reaches into the plastic bag, takes out a pair of Tiger Beat magazines.“I get a discount.”

On the cover of one of the magazines is Justin Timberlake. I take the magazine from her, scrutinize the cover.

“I haven’t liked his solo stuff as much as ’NSYNC,” I say.“What about you?”

Kristi looks at me, her mouth half-open.“I can’t believe you know who he is.”

“Hey,” I say in mock rage.“I’m not that old.” I hand the magazine back, mindful of the fact that my prints are on the glossy surface. I must not forget that.

Kristi shakes her head, still smiling.

We continue up Walnut.

“All ready for Easter?” I ask, rather inelegantly changing the subject.

“Oh, yes,” she says.“I love Easter.”

“Me, too,” I say.

“I mean, I know it’s still real early in the year, but Easter always means summer is coming, to me. Some people wait till Memorial Day. Not me.”

I fall behind her for a few steps, allowing people to pass. From the cover of my sunglasses, I watch her walk, as covertly as I can. In a few years, she would have been what people refer to as coltish, a long-legged beauty.

When I make my move, I am going to have to be fast. Leverage will be paramount. I have the syringe in my pocket, its rubber tip firmly secured.

I glance around. For all the people on the street, lost in their own dramas, we might as well be alone. It never fails to amaze me how, in a city like Philadelphia, one can go virtually unnoticed.

“Where are you headed?” I ask.

“Bus stop,” she says.“Home.”

I pretend to search my memory.“You live in Chestnut Hill, right?” She smiles, rolls her eyes.“Close. Nicetown.”

“That’s what I meant.”

I laugh.

She laughs.

I have her.

“Are you hungry?” I ask.

I watch her face as I ask this. Kristi had done her battles with anorexia, and I know that questions like this will always be a challenge to her in this life. A few moments pass, and I fear I have lost her.

I have not.

“I could eat,” she says.

“Great,” I say.“Let’s get a salad or something, then I’ll drive you home. It’ll be fun.We can catch up.”

A split second of apprehension settles, veiling her pretty face in darkness. She glances around us.

The veil lifts. She slips on her leather jacket, gives her ponytail a flip, and says:“Okay.”

53

WEDNESDAY, 4:20 PM

Eddie Kasalonis retired in 2002.

Now in his early sixties, he had been on the force nearly forty years, most of them in the zone, and had seen it all, from every vantage, in every light, having worked twenty years on the streets before moving to

South detectives.

Jessica had located him through the FOP. She hadn’t been able to reach Kevin, so she went to meet Eddie on her own. She found him where he was every day at this time. At a small Italian eatery on Tenth Street.

Jessica ordered a coffee; Eddie, a double espresso with a lemon peel. “I saw a lot over the years,” Eddie said, clearly as a preface to a walk down memory lane.A big man, with moist gray eyes, a navy tattoo on his right forearm, and shoulders rounded with age. Time had slowed his stories. Jessica had wanted to get right to the business about the blood on the door at St. Katherine but, out of respect, she listened. Eventually, he drained his espresso, called for another, then asked: “So. What can I do for you, Detective?”

Jessica took out her notebook. “I understand you investigated an incident at St. Katherine a few years ago.”

Eddie Kasalonis nodded. “You mean the blood on the door of the church?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t know what I can tell you about it. Wasn’t much of an investigation, really.”

“Can I ask how it was that you came to be involved? I mean, it’s a long way from your stomping grounds.”

Jessica had asked around. Eddie Kasalonis was a South Philly boy. Third and Wharton.

“A priest from St. Casimir’s had just gotten transferred up there. Nice kid. Lithuanian, like me. He called, I said I’d look into it.”

“What did you find?”

“Not much, Detective. Someone painted the lintel over the main doors with blood while the congregation was celebrating midnight mass. When they came out, it dripped onto an elderly woman. She freaked, called it a miracle, called an ambulance.”

“What kind of blood was it?”

“Well, it wasn’t human, I can tell you that. Some kind of animal blood. That’s about as far as we pushed it.”

“Did it ever happen again?”

Eddie Kasalonis shook his head. “That was it, far as I know. They cleaned the door, kept an eye out for a while, then they eventually moved on. As for me, I had a lot on my plate in those days.” The waiter brought Eddie’s coffee, offered Jessica a refill. She declined.

“Did it happen at any other churches?” Jessica asked.

“No idea,” Eddie said. “Like I said, I looked into it as a favor. Church desecration wasn’t exactly my beat.”

“Any suspects?”

“Not really. That part of the Northeast ain’t exactly a hotbed of gang activity. I rousted a few of the local punks, threw a little weight. No one copped to it.”

Jessica put her notebook away, finished her coffee, a little disappointed that this hadn’t led to anything. On the other hand, she hadn’t really expected it to.

“Now it’s my turn to ask,” Eddie said.

“Sure,” Jessica replied.

“What is your interest in a three-year-old vandalism case in Torresdale?”

Jessica told him. No reason not to. Like everyone else in Philly, Eddie Kasalonis was highly aware of the Rosary Killer case. He didn’t press her on the details.

Jessica looked at her watch. “I really do appreciate your time,” she said as she stood up, reached into her pocket to pay for her coffee. Eddie Kasalonis held up his hand, meaning: Put it away.

“Glad to help,” he said. He stirred his coffee, a wistful look coming over his face. Another story. Jessica waited. “You know how, at the racetrack, you sometimes see the old jockeys hanging over the rail, watching the workouts? Or how when you go by a building site and you see the old carpenters sitting on a bench, watching the new buildings go up? You look at these guys and you know they’re just dying to get back into the game.”

Jessica knew where he was going. And she certainly knew about carpenters. Vincent’s father retired a few years ago and these days he sat around, in front of the television, beer in hand, heckling the lousy remodeling jobs on HGTV.

“Yeah,” Jessica said. “I know what you mean.”

Eddie Kasalonis put sugar in his coffee, settled even more deeply into his chair. “Not me. I’m glad I don’t have to do it anymore. When I first heard about this case you’re working, I realized that the world had passed me by, Detective. The guy you’re looking for? Hell, he comes from a place I’ve never been.” Eddie looked up, fixing her in time with his sad, watery eyes. “And I thank God I don’t have to go there.”

Jessica wished she didn’t have to go there, either. But it was a little late for that. She got out her keys, hesitated. “Is there anything else you can tell me about the blood on the church door?”

Eddie seemed to be deliberating over whether or not to say anything. “Well, I’ll tell you. When I looked at the bloodstain, the morning after it happened, I thought I saw something. Everyone else told me I was imagining things, the way people see the face of the Virgin Mary in oil slicks on their driveways, things like that. But I was sure I saw what I thought I saw.”

“What was it?”

Eddie Kasalonis hesitated again. “I thought it looked like a rose,” he finally said. “An upside-down rose.”

...

Jessica had four stops to make before going home. She had to go to the bank, stop at the dry cleaners, pick up something for dinner at a Wawa, and send a package to her Aunt Lorrie in Pompano Beach. The bank, the grocery store, and UPS were all within a few blocks of Second and South.

As she parked the Jeep, she thought about what Eddie Kasalonis had said.

I thought it looked like a rose.An upside-down rose.

From her readings, she knew that the term rosary itself was based on Mary and the rose garden. Thirteenth-century art depicted Mary holding a rose, not a scepter. Did any of this have anything to do with her case, or was she just being desperate?

Desperate.

Definitely.

Still, she’d mention it to Kevin and get his take on it.

She got the box she was taking to UPS out of the back of the Jeep, locked it, headed up the street. When she walked by Cosi, the salad-andsandwich franchise at the corner of Second and Lombard, she looked in the window and saw someone she recognized, even though she really didn’t want to.

Because the someone was Vincent.And he was sitting in a booth with a woman.

A young woman.

Actually, a girl.

Jessica could only see the girl from the back, but that was enough. She had long blond hair, pulled back into a ponytail. She wore a leather jacket, motorcycle style. Jessica knew that badge bunnies came in all shapes, sizes, and colors.

And, obviously, ages.

For a brief moment, Jessica experienced that strange feeling you get like when you’re in another city and you see someone you think you recognize. There’s that flutter of familiarity, followed by the realization that what you’re seeing can’t be accurate, which, in this instance, translated as:

What the hell is my husband doing in a restaurant with a girl who looks about eighteen years old?

Without having to think, the answer came roaring into her head. You son of a bitch.

Vincent saw Jessica, and his face told the story. Guilt, topped by

embarrassment, with a side order of shit-eating grin.

Jessica took a deep breath, looked at the ground, then continued up the street. She was not going to be that stupid, crazed woman who confronts her husband and his mistress in a public place. No way.

Within seconds, Vincent burst through the door.

“Jess,” he said. “Wait.”

Jessica stopped, trying to rein in her anger. Her anger would not hear

it. It was a rabid, stampeding herd of emotion.

“Talk to me,” he said.

“Fuck you.”

“It’s not what you think, Jess.”

She put her package on a bench, spun to face him. “Gee. How did I

know you were going to say that?” She looked at her husband, up and down. It always amazed her how different he could look, based on her feelings at any given moment. When they were happy, his bad-boy swagger and tough-guy posturing were so very sexy. When she was pissed, he looked like a thug, like some street-corner Goodfella wannabe she wanted to slap the cuffs on.

And, God save them both, this was about as pissed off as she’d ever been with him.

“I can explain,” he added.

“Explain? Like you explained Michelle Brown? I’m sorry, what was that, again? A little amateur gynecology in my bed?”

“Listen to me.”

Vincent grabbed Jessica by the arm and, for the first time since they had met, for the first time in their volatile, passionate love affair, it felt as if they were strangers, arguing on a street corner; the kind of couple who, when you are in love, you vow never to become.

“Don’t,” she warned.

Vincent held on tighter. “Jess.”

“Take...your fucking...hand... off me.” Jessica was not at all surprised to find that she had formed both of her hands into fists. The notion scared her a little, but not enough to unclench them. Would she lash out at him? She honestly didn’t know.

Vincent stepped back, putting up his hands in surrender. The look on his face, at that moment, told Jessica that they just crossed a threshold and entered a shadowy territory from which they might never return.

But at the moment, that didn’t matter.

All Jessica could see was a blond ponytail and the goofy smile Vincent had on his face when she caught him.

Jessica picked up her package, turned on her heels, and headed back to the Jeep. Fuck UPS, fuck the bank, fuck dinner. All she could think about was getting away from there.

She hopped in the Jeep, started it and jammed the pedal. She was almost hoping that some rookie patrolman was nearby to pull her over and try to give her some shit.

No luck. Never a cop around when you needed one.

Except the one she was married to.

Before she turned onto South Street she looked in the rearview mirror and saw Vincent still standing on the corner, hands in pockets, a receding, solitary silhouette against the red brick backdrop of Society Hill.

Receding, along with him, was her marriage.

54

WEDNESDAY, 7:15 PM

The night behind the duct tape was a Dalí landscape, black velvet dunes rolling toward a far horizon. Occasionally, fingers of light crept through the bottom part of his visual plane, teasing him with the notion of safety.

His head ached. His limbs felt dead and useless. But that wasn’t the worst of it. If the tape over his eyes was irritating, the tape over his mouth was maddening beyond discourse. For someone like Simon Close, the humiliation of being tied to a chair, bound with duct tape, and gagged with something that felt and tasted like an ancient tack rag finished a distant second to the frustration of not being able to talk. If he lost his words, he lost the battle. It had always been thus. As a small boy, in the Catholic home in Berwick, he had managed to talk his way out of nearly every scrape, every frightful jam.

Not this one.

He could barely make a sound.

The tape was wrapped tightly around his head, just above his ears, so

he was able to hear.

How do I get out of this? Deep breath, Simon. Deep.

Crazily, he thought about the books and CDs he had acquired over the years, the ones dealing with meditation and yoga and the concepts of diaphragmatic breathing, the yogic techniques for fighting stress and anxiety. He had never read a single one, nor listened to more than a few minutes of the CDs. He had wanted a quick fix for his occasional panic attacks—the Xanax made him far too sluggish to think straight—but there was no quick fix to be found in yoga.

Now he wished he had stuck with it.

Save me, Deepak Chopra, he thought.

Help me, Dr.Weil.

Then he heard the door to his flat open behind him. He was back. The sound filled him with a sickening brew of hope and fear. He heard the footsteps approach from behind, felt the weight on the floorboards. He smelled something sweet, floral. Faint, but present.A young girl’s perfume.

Suddenly, the tape was ripped from his eyes. The grease-fire pain made it feel as if his eyelids came off with it.

When his eyes adjusted to the light, he saw, on the coffee table in front of him, his Apple PowerBook, opened and displaying a graphic of The Report’s current web page.

monster stalks philly girls!

Sentences and phrases were highlighted in red.

. . . depraved psychopath . . .

. . . deviant butcher of innocence . . .

Behind the laptop, on a tripod, sat Simon’s digital camera. The camera was on and pointed right at him.

Simon then heard a click behind him. His tormentor had the Apple mouse in his hand and was clicking through the documents. Soon, another article appeared. The article was from three years earlier, a piece he had written about blood being splashed on the door of a church in the Northeast. Another phrase was highlighted:

. . . hark the herald assholes fling . . .

Behind him, Simon heard a satchel being unzipped. Moments later, he felt the slight pinch at the right side of his neck. A needle. Simon struggled mightily against his bindings, but it was useless. Even if he could get loose, whatever was in the needle took almost immediate effect. Warmth spread through his muscles, a pleasurable weakness that, were he not in this situation, he might have enjoyed.

His mind began to fragment, soar. He closed his eyes. His thoughts took flight over the last decade or so of his life. Time leapt, fluttered, settled.

When he opened his eyes, the cruel buffet displayed on the coffee table in front of him arrested the breath in his chest. For a moment, he tried to conjure some sort of benevolent scenario for them. There was none.

Then, as his bowels released, he recorded the final visual entry in his reporter’s mind—a cordless drill, a large needle, threaded with a thick black thread.

And he knew.

Another injection took him to the edge of the abyss. This time, he willingly went along with it.

A few minutes later, when he heard the sound of the drill, Simon Close screamed, but the sound seemed to come from somewhere else, a disembodied wail that echoed off the damp stone walls of a Catholic home in the time-swept north of England, a plaintive sigh over the ancient face of the moors.

55

WEDNESDAY, 7:35 PM

Jessica and Sophie sat at the table, pigging out on all the goodies they had brought home from her father’s house—panettone, sfogliatelle, tiramisu. It wasn’t exactly a balanced meal, but she had blown off the grocery store and there was nothing in the fridge.

Jessica knew it wasn’t a good idea to let Sophie eat so much sugar at this late hour, but Sophie had a sweet tooth the size of Pittsburgh, just like her mother, and, well, it was so hard to say no. Jessica concluded long ago that she had better start saving for the dental bills.

Besides, after seeing Vincent mooning with Britney or Courtney or Ashley, or whatever the hell her name was, tiramisu was just about the right medicine. She tried to exile the image of her husband and the blond teenager from her mind.

Unfortunately, it was immediately replaced by the picture of Brian Parkhurst’s body, hanging in that hot room, the rank smell of death.

The more she thought about it, the more she doubted Parkhurst’s guilt. Had he been seeing Tessa Wells? Perhaps. Was he responsible for the murders of three young women? She didn’t think so. It was nearly impossible to commit a single abduction and homicide without leaving behind trace evidence.

Three of them?

It just didn’t seem feasible.

But what about the PA R on Nicole Taylor’s hand?

For a fleeting moment, Jessica realized that she had signed on for a lot more than she felt she could handle with this job.

She cleaned the table, plopped Sophie down in front of the TV, popped in the Finding Nemo DVD.

She poured herself a glass of Chianti, cleared the dining room table, then spread out all her notes on the case. She walked her mind over the time line of events. There was a connection among these girls, something other than the fact that they attended Catholic schools.

Nicole Taylor, abducted off the street, dumped in a field of flowers.

Tessa Wells, abducted off the street, dumped in an abandoned row house.

Bethany Price, abducted off the street, dumped at the Rodin Museum.

The selection of dump sites seemed in turn random and precise, elaborately staged and mindlessly arbitrary.

No, Jessica thought. Dr. Summers was right. Their doer was anything but illogical. The placement of these victims was every bit as significant as the method of their murder.

She looked at the crime scene photographs of the girls and tried to imagine their final moments of freedom, tried to drag those unfolding moments from the dominion of black and white to the saturated color of nightmare.

Jessica picked up Tessa Wells’s school photograph. It was Tessa Wells who troubled her most deeply; perhaps because Tessa had been the first victim she had seen. Or maybe because she knew that Tessa was the outwardly shy young girl that Jessica had once been, the chrysalis ever yearning to become the imago.

She walked into the living room, planted a kiss on Sophie’s shiny, strawberry-scented hair. Sophie giggled. Jessica watched a few minutes of the movie, the colorful adventures of Dory and Marlin and Gill.

Then her eyes found the envelope on the end table. She had forgotten all about it.

the Rosary girls 273

The Rosarium Virginis Mariae.

Jessica sat down at the dining room table and skimmed the lengthy letter, which seemed to be a missive from Pope John Paul II, affirming the relevance of the holy rosary. She glossed over the headings, but her attention was drawn to one section, a segment titled “Mysteries of Christ, Mysteries of His Mother.”

As she read, she felt a small flame of understanding ignite within her, the realization that she had crossed a barrier that, until this second, had been unknown to her, a barricade that could never be breached again.

She read that there are five “Sorrowful Mysteries” of the rosary. She had, of course, known this from her Catholic school upbringing, but hadn’t thought of it in years.

The agony in the garden.

The scourge at the pillar.

The crown of thorns.

The carrying of the cross.

The crucifixion.

The revelation was a crystalline bullet to the center of her brain. Nicole Taylor was found in a garden. Tessa Wells was bound to a pillar. Bethany Price wore a crown of thorns.

This was the killer’s master plan.

He is going to kill five girls.

For a few anxious moments she didn’t seem to be able to move. She took a few deep breaths, calmed herself. She knew that, if she was right about this, the information would change the investigation completely, but she didn’t want to present the theory to the task force until she was sure.

It was one thing to know the plan, but it was equally important to understand why. Understanding why would go a long way toward knowing where their doer would strike next. She took out a legal pad and made a grid.

The section of sheep bone found on Nicole Taylor was intended to lead investigators to the Tessa Wells crime scene.

But how?

She thumbed through the indices of some of the books she had taken from the Free Library. She found a section on Roman customs, and learned that scourging practices in the time of Christ included a short whip called a flagrum, to which they often attached leather thongs of variable lengths. Knots were tied in the ends of each thong, and sharp sheep bones were inserted into the knots at the ends.

The sheep bone meant there would be a scourge at the pillar.

Jessica wrote notes as fast as she could.

The reproduction of Blake’s painting Dante and Virgil at the Gates of Hell that was found inside Tessa Wells’s hands was obvious. Bethany Price was found at the gates leading into the Rodin Museum.

An examination of Bethany Price had found that she had two numbers written on the insides of her hands. On her left hand was the number 7. On her right hand, the number 16. Both numbers were written in black magic marker.

716.

Address? License plate? Partial zip code?

So far, no one on the task force had had any idea what the numbers meant. Jessica knew that, if she could divine this secret, there was a chance they could anticipate where the murderer’s next victim would be placed. And they could be waiting for him.

She stared at the huge pile of books on the dining room table. She was certain the answer was somewhere in one of them.

She walked into the kitchen, dumped the glass of red wine, put on a pot of coffee.

It was going to be a long night.

WEDNESDAY, 11:15 PM

The headstone is cold. The name and date are obscured by time and windborne debris. I clean it off. I run my index finger along the chiseled numbers. The date brings me back to a time in my life when all things were possible. A time when the future shimmered.

I think about who she would have been, what she might have done with her life, who she might have become.

Doctor? Politician? Musician? Teacher?

I watch the young women and I know the world is theirs.

I know what I have lost.

Of all the sacred days on the Catholic calendar, Good Friday is, perhaps, the most sacred. I’ve heard people ask: If this is the day that Christ was crucified, why is it called good? Not all cultures call it Good Friday.The Germans call it Charfreitag, or Sorrowful Friday. In Latin it has been called Parasceve, the word meaning preparation.

Kristi is in preparation.

Kristi is praying.

When I left her, secured and snug in the chapel, she was on her tenth rosary. She is very conscientious and, from the way she earnestly says the decades, I can tell that she wants to please not only me—after all, I can only affect her mortal life—but the Lord, as well.

The chilled rain slicks the black granite, joining my tears, flooding my heart full of storms.

I pick up the shovel, begin to dig the soft earth.

The Romans believed that there was significance to the hour that signaled the close of the business day, the ninth hour, the time when fasting began.

They called it the Hour of None.

For me, for my girls, the hour is finally near.

THURSDAY, 8:05 A M

The parade of police cars, both marked and unmarked, that snaked their way up the rain-glassed street in West Philadelphia where Jimmy Purify’s widow made her home seemed endless.

Byrne had gotten the call from Ike Buchanan at just after six. Jimmy Purify was dead. He had coded at three that morning. As he walked toward the house, Byrne fielded hugs from other detectives. Most people thought it was tough for cops to show emotion– some said the lack of sentiment was a prerequisite for the job—but every cop knew better. At a time like this, nothing came easier.

When Byrne entered the living room he considered the woman standing in front of him, frozen in time and space in her own house. Darlene Purify stood at the window, her thousand-yard stare reaching far beyond the gray horizon. The TV babbled in the background, a talk show. Byrne thought about turning it off, but realized that the silence would be far worse. The TV indicated that life, somewhere, went on.

“Where do you want me, Darlene? You tell me, I go there.”

Darlene Purify was just over forty, a former R&B singer in the 1980s, having even cut a few records with an all-girl group called La Rouge. Now her hair was platinum, her once slight figure given to time. “I stopped loving him a long time ago, Kevin. I don’t even remember when. It’s just... the idea of him that’s missing. Jimmy. Gone. Shit.”

Byrne walked across the room, held her. He stroked her hair, searching for words. He found some. “He was the best cop I ever knew. The best.”

Darlene dabbed her eyes. Grief was such a heartless sculptor, Byrne thought. At that moment, Darlene looked a dozen years older than she was. He thought about the first time they had met, in such happy times. Jimmy had brought her to a Police Athletic League dance. Byrne had watched Darlene shake it up with Jimmy, wondering how a player like him ever landed a woman like her.

“He loved it, you know,” Darlene said.

“The job?”

“Yeah. The job,” Darlene said. “He loved it more than he ever loved

me. Or even the kids, I think.”

“That’s not true. It’s different, you know? Loving the job is...

well... different. I spent every day with him after the divorce. A lot of

nights, too. Believe me, he missed you more than you’ll ever know.” Darlene looked at him, as if this were the most incredible thing she

had ever heard. “He did?”

“You kidding? You remember that monogrammed hankie? The little

one of yours with the flowers in the corner? The one you gave him on

your first date?”

“What...what about it?”

“He never went out on a tour without it. In fact, we were halfway to

Fishtown one night, heading to a stakeout, and we had to head back to the

Roundhouse because he forgot it.And believe me, you didn’t give him lip

about it.”

Darlene laughed, then covered her mouth and began to cry again.

Byrne didn’t know if he was making it better or worse. He put his hand

on her shoulder until her sobbing began to subside. He searched his

memory for a story, any story. For some reason, he wanted to keep Darlene talking. He didn’t know why, but he felt that, if she was talking, she

wouldn’t grieve.

“Did I ever tell you about the time Jimmy went undercover as a gay

prostitute?”

“Many times.” Darlene smiled now, through the salt. “Tell me again,

Kevin.”

“Well, we were working a reverse sting, right? Middle of summer.

Five detectives on the detail, and Jimmy’s number was up to be the bait.

We laughed about it for a week beforehand, right? Like, who the hell was

ever gonna believe that big slab of pork was sellin’ it? Forget sellin’ it,

who the hell was gonna buy?”

Byrne told her the rest of the story by rote. Darlene smiled at all the

right places, laughed her sad laugh at the end. Then she melted into

Byrne’s big arms and he held her for what seemed like minutes, waving

off a few cops who had shown up to pay their respects. Finally he asked:

“Do the boys know?”

Darlene wiped her eyes. “Yeah. They’ll be in tomorrow.” Byrne squared himself in front of her. “If you need anything, anything

at all, you pick up the phone. Don’t even look at the clock.” “Thanks, Kevin.”