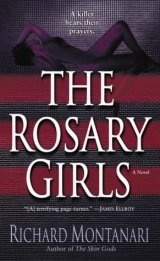

Текст книги "The Rosary Girls"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Маньяки

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“And don’t worry about the arrangements. The association’s all over

it. It’s gonna be a procession like the pope.”

Byrne looked at Darlene. The tears came again. Kevin Byrne held her

close, felt her heart racing. Darlene was tough, having survived both her

parents’ slow deaths from lingering illness. It was the boys he worried

about. None of them had their mother’s backbone. They were sensitive

kids, very close to each other, and Byrne knew that one of his jobs, in the

next few weeks, would be shoring up the Purify family.

When Byrne walked out of Darlene’s house, he had to look both ways on the street. He couldn’t remember where he had parked the car. The headache was a sharp dagger between his eyes. He tapped his pocket. He still had full scrip of Vicodin.

You’ve got a full plate, Kevin, he thought. Shape the hell up. He lit a cigarette, took a few moments, got his bearings. He looked at his pager. There were still three calls from Jimmy that he’d never returned.

There will be time.

He finally remembered that he had parked on a side street. By the time he reached the corner, the rain began again. Why not, he thought. Jimmy was gone. The sun dared not show its face. Not today. All over the city—in diners and cabs and beauty parlors and boardrooms and church basements—people were talking about the Rosary Killer, about how a madman was feasting on the young girls of Philadelphia, and how the police couldn’t stop him. For the first time in his career, Byrne felt impotent, thoroughly inadequate, an impostor, as if he couldn’t look at his paycheck with any sense of pride or dignity.

He stepped into the Crystal Coffee Shop, a twenty-four-hour spoon he had frequented many mornings with Jimmy. There was a pall over the regulars. They’d heard the news. He grabbed a paper and a large coffee, wondering if he’d ever be back. When he exited, he saw that someone was leaning against his car.

It was Jessica.

The emotion almost took his legs.

This kid, he thought. This kid is something.

“Hey there,” she said.

“Hey.”

“I was sorry to hear about your partner.”

“Thanks,” Byrne said, trying to keep it all in check. “He was...he was one of a kind.You would’ve liked him.”

“Is there anything I can do?”

She had a way about her, Byrne thought. A way that made questions like that sound sincere, not like the bullshit that people say just to go on record.

“No,” Byrne said. “Everything’s under control.”

“If you want to take the day...”

Byrne shook his head. “I’m good.”

“You sure?” Jessica asked.

“Hundred percent.”

Jessica held up the Rosarium letter.

“What’s that?” Byrne asked.

“I think it’s the key to our guy’s mind.”

Jessica briefed him on what she had learned, along with details of her meeting with Eddie Kasalonis. As she talked, she saw a number of things crawl across Kevin Byrne’s face. Two of them mattered most.

Respect for her as a detective.

And, more importantly, determination.

“There’s somebody we should talk to before we brief the team,” Jessica said. “Somebody who could put this all in perspective.”

Byrne turned and looked once, briefly, toward Jimmy Purify’s house. He turned back and said: “Let’s rock.”

They sat with Father Corrio at a small table near the front window of Anthony’s, a coffeehouse on Ninth Street in South Philly.

“There are twenty mysteries of the rosary in all,” Father Corrio said. “They are grouped into four groups. The Joyful, The Sorrowful, The Glorious, and the Luminous.”

The notion that their doer was planning twenty murders was not lost on anyone at that table. Father Corrio didn’t seem to think that was the case.

“Strictly speaking,” he continued, “the mysteries are assigned days of the week. The Glorious Mysteries are observed on Sunday and Wednesday, the Joyful Mysteries on Monday and Saturday. The Luminous Mysteries, which are relatively new, are observed on Thursday.”

“What about the Sorrowful?” Byrne asked.

“The Sorrowful Mysteries are observed on Tuesday and Friday. Sundays during Lent.”

Jessica did the math in her head, counting back the days from the discovery of Bethany Price. It didn’t fit the pattern of observance.

“The majority of the mysteries are celebratory,” Father Corrio said. “They include the Annunciation, the baptism of Jesus, the Assumption, the resurrection of Christ. It is only the Sorrowful Mysteries that deal with suffering and death.”

“And there are only five Sorrowful Mysteries, right?” Jessica asked.

“Yes,” Father Corrio said. “But keep in mind that the rosary is not universally accepted. There are objectors.”

“How so?” Jessica asked.

“Well, there are those who find the rosary unecumenical.”

“Not sure what you mean,” Byrne said.

“The rosary celebrates Mary,” Father Corrio said. “It venerates the mother of God, and some believe that the Marian character of the prayer does not glorify Christ.”

“How does that apply to what we’re facing here?”

Father Corrio shrugged. “Perhaps the man you seek does not believe in the virginal state of Mary. Perhaps he is, in his own sick way, trying to return these girls to God in such a state.”

The thought sent a shudder through Jessica. If that was his motive, then when, and why, would he ever stop?

Jessica reached into her folio, held up the photographs of the insides of Bethany Price’s palms, the numbers 7 and 16.

“Do these numbers mean anything to you?” Jessica asked.

Father Corrio slipped on his bifocals, looked at the photos. It was apparent that the wounds caused by the drill through the young girl’s hands were disturbing to him.

“It could be many things,” Father Corrio said. “Nothing comes immediately to mind.”

“I checked page seven hundred sixteen in the Oxford Annotated Bible,” Jessica said. “It was in the middle of the book of Psalms. I read the text, but nothing jumped out.”

Father Corrio nodded, but remained silent. It was clear that the book of Psalms, in this context, didn’t strike a chord within him.

“What about a year? Does the year seven sixteen have any significance in the church that you know of?” Jessica asked.

Father Corrio smiled. “I minored in English, Jessica,” he said. “I’m afraid that history was not my best subject. Outside of knowing that Vatican One was convened in 1869, I’m not much good on dates.”

Jessica went through the scribbled notes she had taken the night before. She was running out of ideas.

“Did you happen to find a scapular on this girl by any chance?” Father Corrio asked.

Byrne went through his notes. A scapular was essentially two small, square pieces of woolen cloth connected to each other by two strings or bands. It was worn in such a way that, when the bands rested on the shoulders, one segment rested in the front, while the other rested in the back. Usually, scapulars were given as a gift for the first communion—a gift set that often included a rosary, a chalice-and-host pin, and a satin bag.

“Yes,” Byrne said. “She had a scapular around her neck when she was found.”

“Is it a brown scapular?”

Byrne scanned his notes again. “Yes.”

“You might want to look closely at it,” Father Corrio said.

Quite often, scapulars were encased in clear plastic to protect them, as was the one found on Bethany Price. Her scapular had already been dusted for prints. None had been found. “Why is that, Father?”

“Every year there is a feast of the Scapular, a day devoted to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. It is the anniversary of the day the Blessed Virgin appeared to Saint Simon Stock and presented him with a monk’s scapular. She told him that whoever wore it would not suffer eternal fire.”

“I don’t understand,” Byrne said. “Why is that relevant?”

Father Corrio said: “The Feast of the Scapular is celebrated on July 16th.”

The scapular found on Bethany Price was indeed a brown scapular, dedicated to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Byrne phoned the lab and asked if they had opened the clear plastic case. They had not.

Byrne and Jessica headed back to the Roundhouse.

“You know, the possibility exists that we might not catch this guy,” Byrne said. “He might get to his fifth victim, then crawl back into the slime forever.”

The notion had crossed Jessica’s mind. She had been trying not to think about it. “You think that might happen?”

“I hope not,” Byrne said. “But I’ve been at this a while. I just want you to be prepared for the possibility.”

The possibility did not sit well with her. If this man was not caught, she knew that, for the rest of her career in the Homicide Unit, for the rest of her time in law enforcement, she would judge every case by what she would consider a failure.

Before Jessica could respond, Byrne’s cell phone rang. He answered. Within seconds, he closed the phone, reached into the backseat for the deck strobe light. He put it on the dash and lighted it.

“What’s up?” Jessica asked.

“They opened the scapular and dusted the inside,” he said. He slammed the gas pedal to the floor. “We’ve got a print.”

They waited on a bench outside the print lab.

There are all kinds of waiting in police work. There’s the stakeout variety, the verdict variety. There’s the type of waiting when you show up in a municipal courtroom to testify in some bullshit DUI case at nine in the morning, only to get on the stand for two minutes at three in the afternoon, just in time to start your tour at four.

But waiting for a print to come up was the best and the worst waiting.You had evidence, but the longer it took, the more likely it was that you would not get a usable match.

Byrne and Jessica tried to get comfortable. There were a number of other things they could be doing in the meantime, but they were bound and determined to do none of them. Their main objective, at the moment, was to keep both blood pressure and pulse rate down.

“Can I ask you something?” Jessica asked.

“Sure.”

“If you don’t want to talk about it, I totally understand.” Byrne looked at her, his green eyes nearly black. She had never seen a

man look quite so exhausted.

“You want to know about Luther White,” he said.

“Well.Yeah,” Jessica said. Was she that transparent? “Kinda.” Jessica had asked around. Detectives were protective of their own.

The bits and pieces she had heard added up to a pretty crazy story. She figured she’d just ask.

“What do you want to know?” Byrne asked.

Every last detail. “Whatever you want to tell me.”

Byrne slid down on the bench a little, arranged his weight. “I had been on the job about five years or so, in plain clothes for about two. There had been a series of rapes in West Philly. The doer’s MO was to hang out in the parking lots of places like motels, hospitals, office buildings. He’d strike in the middle of the night, usually between three and four in the morning.”

Jessica vaguely remembered. She was in ninth grade, and the story scared the hell out of her and her friends.

“The doer wore a nylon stocking over his face, rubber gloves, and he always wore a condom. Never left a hair, a fiber. Not a drop of fluid. We had nothing. Eight women over a three-month period and we had zero. The only description we had, other than the guy was white and somewhere between thirty and fifty, was that he had a tattoo on the front of his neck. An elaborate tattoo of an eagle that went all the way up to the base of his jaw. We interviewed every tat parlor between Pittsburgh and Atlantic City. Nothing.

“So one night I’m out with Jimmy. We had just taken down a suspect in Old City and were still suited up. We stopped for a quick one at this place called Deuces, out by Pier Eighty-four. We were just getting ready to leave when I see that a guy at one of the tables by the door is wearing a white turtleneck, pulled high. I don’t think anything of it right away, but as I walk out the door I turn around for some reason, and I see it. The tip of a tattoo peeking out over the top of the turtleneck. An eagle’s beak. Couldn’t have been more than a half-inch, right? It was him.”

“Did he see you?”

“Oh yeah,” Byrne said. “So me and Jimmy just leave. We huddle outside, right by this low stone wall that’s right next to the river, figuring we’d call it in, seeing as we just had a few and we didn’t want anything to get in the way of us putting this fucker away. This is before cell phones, so Jimmy heads to the car to call for backup. I decide I’m going to go stand next to the door, figuring, if this guy tries to leave, I’ll get the drop on him. But as soon as I turn around, there he is. And he’s got this twentytwo pointed right at my heart.”

“How did he make you?”

“No idea. But without a word, without hesitation, he unloads. Fired three shots, rapid succession. I took them all in the vest, but they knocked the wind out of me. His fourth shot grazed my forehead.” At this, Byrne fingered the scar over his right eye. “I went back, over the wall, into the river. I couldn’t breathe. The slugs had cracked two ribs, so I couldn’t even try to swim. I just started to sink to the bottom, like I was paralyzed. The water was cold as hell.”

“What happened to White?”

“Jimmy took him down. Two to the chest.”

Jessica tried to wrap her mind around the images, the nightmare every cop has of facing down a two-time loser with a weapon.

“As I was sinking, I saw White hit the surface above me. I swear, before I went unconscious, we had a moment when were face-to-face under the water. Inches apart. It was dark, and it was freezing, but we locked eyes. We were both dying, and we knew it.”

“What happened next?”

“They fished me out, did CPR, the whole routine.”

“I heard that you...” For some reason Jessica found it hard to say the word.

“Drowned?”

“Well, yeah. That. Did you?”

“So they tell me.”

“Wow. How long were you, um...”

Byrne laughed. “Dead?”

“Sorry,” Jessica said. “I can safely say that I’ve never asked that question before.”

“Sixty seconds,” Byrne replied.

“Wow.”

Byrne looked over at Jessica. Her face was a press conference of questions.

Byrne smiled, asked: “You want to know if there were bright white lights and angels and golden trumpets and Roma Downey floating overhead, right?”

Jessica laughed. “I guess I do.”

“Well, there was no Roma Downey. But there was a long hallway with a door at the end. I just knew that I shouldn’t open the door. If I opened the door, I was never coming back.”

“You just knew?”

“I just knew.And for a long time, after I got back, whenever I got to a crime scene, especially the scene of a homicide, I got a... feeling. The day after we found Deirdre Pettigrew’s body, I went back to Fairmount Park. I touched the bench in front of the bushes where she was found. I saw Pratt. I didn’t know his name, I couldn’t see his face clearly, but I knew it was him. I saw how she saw him.”

“You saw him?”

“Not in the visual sense. I just...knew.” It was clear that none of this was easy for him. “It happened a lot for a long time,” he said. “There was no explaining it. No predicting it. In fact, I did a lot of things I shouldn’t have to try and get it to stop.”

“How long were you IOD?”

“I was out for almost five months. Lots of rehab. That’s where I met my wife.”

“She was a physical therapist?”

“No, no. She was recovering from a torn Achilles tendon. I had actually met her years earlier in the old neighborhood, but we got reacquainted in the hospital. We hobbled up and down the hallways together. I’d say it was love at first Vicodin if it wasn’t such a bad joke.”

Jessica laughed anyway. “Did you ever get any kind of professional psychiatric help?”

“Oh, yeah. I did two years with the department shrink, on and off. Went through dream analysis. Even went to a few IANDS meetings.”

“IANDS?”

“International Association for Near Death Studies. Wasn’t for me.” Jessica tried to take all this in. It was a lot. “So what’s it like now?” “It doesn’t happen all that often these days. Kind of like a faraway TV

signal. Morris Blanchard is proof that I can’t be sure anymore.”

Jessica could see that there was more to the story, but she felt as if she had pushed him enough.

“And, to answer your next question,” Byrne continued. “I can’t read minds, I can’t tell fortunes, I can’t see the future. No Dead Zone here. If I could see the future, believe me, I’d be at Philadelphia Park right now.”

Jessica laughed again. She was glad she had asked, but she was still a little spooked by it all. She had always been a little spooked by stories of clairvoyance and the like. When she read The Shining she slept with the lights on for a week.

She was just about to try one of her clumsy segues to another topic when Ike Buchanan came blasting out of the door to the print lab. His face was flushed, the veins on his neck pulsed. For the moment, his limp was gone.

“Got him,” Buchanan said, waving a computer readout.

Byrne and Jessica shot to their feet, fell into step beside him.

“Who is he?” Byrne asked.

“His name is Wilhelm Kreuz,” Buchanan said.

58

THURSDAY, 11:25 A M

According to DMV records, Wilhelm Kreuz lived on Kensington Avenue. He worked as a parking lot attendant in North Philly. The strike force headed to the location in two vehicles. Four members of the SWAT team rode in a black van. Four of the six detectives on the task

force followed in a department car: Byrne, Jessica, John Shepherd, and Eric Chavez.

A few blocks from the location, a cell phone rang in the Taurus. All four detectives checked their mobiles. It was John Shepherd’s. “Yeah... how long...okay... thanks.” He slid the antenna, folded the phone. “Kreuz hasn’t been in to work for the past two days. No one at the lot has seen him or talked to him.”

The detectives assimilated this, remained silent. There is a ritual that attends hitting the door, any door; a private interior monologue that is different for every law enforcement officer. Some fill the time with prayer. Some, with blank silence. All of it intended to cool the rage, calm the nerves.

They had learned more about their subject. Wilhelm Kreuz clearly fit the profile. He was forty-two years old, a loner, a graduate of the University of Wisconsin.

And although he had a long sheet, there was nothing close to the level of violence or the depth of depravity of the Rosary Girl murders. Still, he was far from a model citizen. Kreuz was a registered Level Two sex offender, meaning he was considered a moderate risk to re-offend. He had done a six-year stint in Chester, registering with authorities in Philadelphia upon his release in September 2002. He had a history of contact with minor females between the ages of ten and fourteen. His victims were both known and unknown to him.

The detectives agreed that, although the victims of the Rosary Killer were older than the profile of Kreuz’s previous victims, there was no logical explanation as to why his fingerprint would be found on a personal item belonging to Bethany Price. They had contacted Bethany Price’s mother and asked if she knew Wilhelm Kreuz.

She did not.

Kreuz lived in a second-floor, three-room apartment in a dilapidated building near Somerset. The street entrance was beside the door to a long-shuttered dry cleaner. According to building department plans, there were four apartments on the second floor.According to the housing authority, only two were occupied. Legally, that is. The back door to the building emptied into an alley that ran the length of the block.

The target apartment was in the front, its two windows overlooking Kensington Avenue. A SWAT sharpshooter took a position across the street, on the roof of a three-story building. A second SWAT officer covered the rear of the building, deployed on the ground.

The remaining two SWAT officers would take down the door with a Thunderbolt CQB battering ram, the heavy cylindrical ram they used whenever a high-risk, dynamic entry was required. Once the door was breached, Jessica and Byrne would enter, with John Shepherd covering the rear flank. Eric Chavez was deployed at the end of the hall, next to the stairs.

They drilled the lock on the street door and gained entry in short order.As they filed across the small lobby, Byrne checked the row of four mailboxes. None was apparently in use. They had long ago been pried open, and never fixed. The floor was littered with scores of handbills, menus, and catalogs.

Above the mailboxes was a moldy corkboard.A few local enterprises barked their wares in fading dot matrix print, printed on curling, hot neon stock. The specials were dated nearly a year earlier. It seemed the people who hawked flyers in this neighborhood had long ago given up on this place. The lobby walls were scarred with gang tags and obscenities in at least four languages.

The stairwell up to the second floor was stacked with trash bags, ripped and scattered by a menagerie of urban animals, two– and fourlegged alike. The stench of rotting food and urine was pervasive.

The second floor was worse. The heavy pall of sour pot smoke lounged beneath the smell of excrement. The second-floor corridor was a long, narrow walkway of exposed metal lath and dangling electrical wire. Peeling plaster and chipped enamel paint hung from the ceiling in damp stalactites.

Byrne stepped quietly up to the target door, placed his ear against it. He listened for a few moments, then shook his head. He tried the knob. Locked. He stepped away.

One of the two SWAT officers made eye contact with the entry team. The other SWAT officer, the one with the ram, got into position. He counted them silently down.

It was on.

“Police! Search warrant!” he yelled.

He drew back the ram then smashed it into the door, just below the

lock. Instantly the old door splintered away from the jamb, then tore off at its upper hinge. The officer with the ram pulled back as the other SWAT officer rolled the jamb, his .223-caliber AR-15 rifle high.

Byrne was in next.

Jessica followed, her Glock 17 pointed low, at the floor. The small living room was directly to the right. Byrne sidled up to

the wall. They were first accosted by the smells of disinfectant, cherry incense, and moldering flesh. A pair of startled rats scurried against the near wall. Jessica noted dried blood on their graying snouts. Their claws clicked on the dry wood floor.

The apartment was sinister-quiet. Somewhere in the living room a spring clock ticked. There were no voices, no breathing.

Ahead was the unkempt living area.A stained gold crushed-velvet love seat, cushions on the floor. A few Domino’s boxes, picked and chewed clean. A pile of filthy clothing.

No humans.

To the left, a door to what was probably the bedroom. It was closed. As they drew closer, from inside the room, they could hear the faint sounds of a radio broadcast. A gospel channel.

The SWAT officer got into position, his rifle high.

Byrne stepped up, touched the door. It was latched. He turned the knob slowly, then quickly pushed open the bedroom door, slid back. The radio was a little louder now.

“The Bible says without question-uh that one day everyone-uh will give an account of themselves-uh to God!”

Byrne made eye contact with Jessica. With a nod of his chin, he counted down. They rolled into the room.

And saw the inside of hell itself.

“Oh, Jesus,” the SWAT officer said. He made the sign of the cross. “Oh Lord Jesus.”

The bedroom held neither furniture nor furnishings of any kind. The walls were covered in peeling, water-stained floral wallpaper; the floor was dotted with dead insects, small bones, more fast-food trash. Cobwebs lined the corners; years of silken gray dust covered the baseboards. The small radio sat in the corner, near the front windows, windows covered with torn and mildewed bedsheets.

Inside the room were two occupants.

Against the far wall, a man was hung upside down on a makeshift cross, a cross that appeared to be fashioned from two pieces of a metal bed frame. His wrists, feet, and neck were bound to the frame with concertina wire that carved deep into his flesh. The man was naked and had been slit down the center of his body from his groin to his throat—fat, skin, and muscle were pulled to the sides to form a deep furrow. He was also slashed laterally across his chest, forming a cruciform shape of blood and shredded tissue.

Beneath him, at the base of the cross, sat a young girl. Her hair, which may have been blond at one time, was deep sienna. She was soaked with blood, a shiny pool of which had puddled in the lap of her denim skirt. The room was filled with the metallic taste of it. The girl’s hands were bolted together. She held a rosary with only one decade of beads.

Byrne recovered from the sight first. There was still danger in this place. He slid along the wall opposite the window, peered into the closet. It was empty.

“Clear,” Byrne finally said.

And while any immediate threat, at least from a living human being, was over, and the detectives could have holstered their weapons, they hesitated, as if they could somehow vanquish the profane vision in front of them by deadly force.

It was not to be.

The killer had come here and left in his wake this blasphemous tableau, a picture that would certainly live in all of their minds for as long as they drew breath.

A quick search of the bedroom closet yielded little. A pair of work uniforms, a pile of soiled underwear and socks. The two uniforms were from Acme Parking. Attached to the front of one of the work shirts was a photo ID tag. The tag identified the hanging man as Wilhelm Kreuz. The ID matched his mug shot.

At long last, the detectives holstered their weapons.

John Shepherd called for the CSU team.

“It’s his name,” the still-shaken SWAT officer said to Byrne and Jessica. The tag on the officer’s dark blue BDU jacket read d. maurer.

“What do you mean?” Byrne asked.

“My family is German,” Maurer said, trying his best to compose himself. It was a difficult task for all of them. “Kreuz is cross in German. His name is William Cross in English.”

The fourth Sorrowful Mystery is the carrying of the cross.

Byrne left the scene for a moment then quickly returned. He flipped through his notebook, looking for the list of young girls for whom missing-person reports had been filed. The reports contained photos as well. It didn’t take long. He crouched down next to the girl, held a photograph by her face. The victim’s name was Kristi Hamilton. She was sixteen. She lived in Nicetown.

Byrne stood up. He took in the horrific scene in front of him. In his mind, deep in the catacombs of his terror, he knew he would soon face this man, and they would both walk to the edge of the void together.

Byrne wanted to say something to the team, a squad he had been selected to lead, but he felt like anything but a leader at that moment. For the first time in his career, he found that no words would suffice.

On the floor, next to Kristi Hamilton’s right leg, was a Burger King cup with a lid and a straw.

There were lip prints on the straw.

The cup was half full of blood.

Byrne and Jessica walked aimlessly, a block or so down Kensington, alone with images of the shrieking insanity of the crime scene. The sun made a brief, timid appearance between a pair of thick gray clouds, casting a rainbow over the street, but not over their moods.

They both wanted to talk.

They both wanted to scream.

They remained silent for now, the storm roiling inside. The general public operated under the illusion that police officers

can look at any scene, any event, and maintain a clinical detachment from it. Granted, the image of the untouchable heart was something a lot of cops cultivated. That image was for television and movies.

“He’s laughing at us,” Byrne said.

Jessica nodded. There was no doubt about it. He had led them to the Kreuz apartment with the planted print. The hardest part of this job, she was learning, was to relegate the desire for personal vengeance to the back of your mind. It was getting harder and harder.

The level of violence was escalating. The sight of Wilhelm Kreuz’s eviscerated corpse told them that this would not end with a peaceful arrest. The Rosary Killer’s rampage was going to end in a bloody siege.

They stood in front of the apartment, leaned against the CSU van.

After a few moments, one of the uniformed officers leaned out the window in Kreuz’s bedroom.

“Detectives?”

“What’s up?” Jessica asked.

“You might want to get up here.”

The woman appeared to be in her late eighties. Her thick glasses prismed rainbows in the spare, incandescent light thrown by the two bare bulbs in the hallway ceiling. She stood just inside her door, leaning over an aluminum walker. She lived two doors down from Wilhelm Kreuz’s apartment. She smelled like cat litter, Bengay, and kosher salami. Her name was Agnes Pinsky.

The uniform said: “Tell this gentleman what you just told me,

ma’am.”

“Huh?”

Agnes wore a torn, sea-foam terry housecoat, buttoned a single button off. The left side hem was higher than the right, revealing knee-high support hose and a calf-length blue wool sock.

“When was the last time you saw Mr. Kreuz?” Byrne asked. “Willy? He’s always nice to me,” she said.

“That’s great,” Byrne said. “When did you see him last?” Agnes Pinsky looked from Jessica to Byrne, back. It seemed she just

realized she was talking to strangers. “How did you find me?” “We just knocked on your door, Mrs. Pinsky.”

“Is he sick?”

“Sick?” Byrne asked. “Why do you say that?”

“His doctor was here.”

“When was his doctor here?”

“Yesterday,” she said. “His doctor came to see him yesterday.” “How do you know it was a doctor?”

“How do I know? Hell’s a matter with you? I know what doctors look

like. I don’t have old timer’s.”

“Do you know what time the doctor came?”

Agnes Pinsky stared at Byrne for an uncomfortable amount of time.

Whatever she had been talking about had slid back into the murky recesses of her mind. She had the look of someone waiting impatiently for her change at the post office.

They would send up a sketch artist, but the chances of getting a workable image were slim.

Still, from what Jessica knew about Alzheimer’s and dementia, certain images were quite often razor sharp.

His doctor came to see him yesterday.

There was only one Sorrowful Mystery left, Jessica thought as she descended the steps.