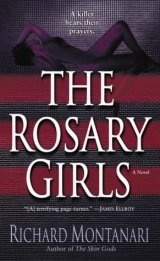

Текст книги "The Rosary Girls"

Автор книги: Richard Montanari

Жанры:

Маньяки

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

pa rt t wo 7

MONDAY, 12:20 PM

Simon Close, the star reporter for Philadelphia’s leading weekly shock tabloid, The Report, had not set foot in a church in more than two decades and, although he didn’t exactly expect the heavens to part and a bolt of righteous lightning to split the sky and rend him in

half, leaving him a smoldering pile of fat and bone and gristle if he did so, there was enough residual Catholic guilt inside him to give him a moment’s pause if he ever entered a church, dipped his finger in the holy water, and genuflected.

Born thirty-two years ago in Berwick-upon-Tweed in the Lake District, the rugged north of England that abuts the border of Scotland, a fell rat of the first order, Simon had never been one to put too much faith in anything, not the least of which was the church. The scion of an abusive father and a mother too drunk to notice or care, Simon had long ago learned to put whatever belief he had in himself.

He had lived in half a dozen Catholic group homes by the time he was seven—where he had learned many things, none of them reflecting the life of Christ—after which he was pawned off on the one and only relative willing to take him in, his spinster aunt Iris who lived in Shamokin, Pennsylvania, a small town about 130 miles northwest of Philadelphia.

Aunt Iris had taken Simon to Philadelphia many times when he was young. Simon recalled seeing the tall buildings, the vast bridges, smelling the city smells and hearing the bustle of urban life, and knew—knew as fully as the realization that he would, no matter what, hang on to his Northumberland inflections at all costs—that one day he would live there.

At sixteen, Simon interned as a copy dog at the News-Item, the local Coal Township daily paper, his eye, like everyone working at any rag east of the Alleghenies, on the city desk at The Philadelphia Inquirer or The Daily News. But after two years of running copy from the editorial office to the typesetter in the basement, and writing the occasional listing and schedule for the Shamokin Oktoberfest, he saw the light, a radiance that had yet to dim.

On a storm-lashed New Year’s Eve, at the newspaper’s offices on Main Street, Simon was sweeping up when he saw a glow from the newsroom. When he peeked in, he saw two men. The paper’s leading light, a man in his fifties named Norman Watts, was poring over the enormous Pennsylvania Code.

The man who covered arts and entertainment, Tristan Chaffee, was wearing a shiny tux, his tie down, his feet up, a glass of white Zinfandel in his hand. He was working on a story about a local celebrity—an overrated singer of syrupy love songs, a low-rent Bobby Vinton—who had apparently been caught in a child porn sting.

Simon pushed his broom, covertly watching the two men work. The serious journalist pored over obscure details of land plots and abstracts and eminent domain rights, rubbing his eyes, butting out long-ashed cigarette after cigarette, forgetting to smoke them, making frequent trips to the loo to drain what must have been a pea-sized bladder.

And then there was the entertainment hack, sipping sweet wine, chatting on the phone with record producers, club owners, groupies.

The decision made itself.

Sod the hard news, Simon had thought.

Gimme the white Zin.

At eighteen, Simon enrolled at the Luzerne County Community College. A year after graduation, Aunt Iris passed silently in her sleep. Simon packed his few belongings and moved to Philly, at long last loping after his dream (that being, becoming the British Joe Queenan). For three years he lived on his small inheritance, trying to sell his freelance articles to the major national glossies, with no luck.

Then, after three more years of writing freelance music and film reviews for the Inquirer and Daily News, and eating his share of ramen noodles and hot ketchup soup, Simon landed a feature job at a new start-up tabloid called The Report. He worked his way up quickly, and for the past seven years Simon Close had written a weekly discourse of his own design called “Up Close!,” a rather lurid crime beat column that covered the city of Philadelphia’s more shocking crimes and, when he was so blessed, the transgressions of its more luminous citizens. In these areas Philadelphia rarely disappointed.

And while his venue at The Report—the conscience of philadelphia read the tag—was not the Inquirer or The Daily News or even CityPaper, Simon had managed to file near the top of the news cycle on a number of big stories, much to the consternation of his far-better-paid colleagues in the so-called legitimate press.

So-called because, according to Simon Close, there was no such thing as the legitimate press. They were all knee deep in the cesspool, every hack with a spiral-bound notebook and acid reflux disease, and the ones who considered themselves solemn chroniclers of their times were seriously deluded. Connie Chung spending a week shadowing Tonya Harding and the “reporters” from Entertainment Tonight covering the JonBenet Ramsey and Laci Peterson cases were all the blur one needed.

Since when were dead little girls entertainment?

Since serious news was flushed down the toilet with an O. J. chaser, that’s when.

Simon was proud of his work at The Report. He had good instincts and an almost photographic memory for quotes and details. He had been front and center on the story of the homeless man found in North Philly, his internal organs removed from his body, as well as the scene of the crime. On that one, Simon had bribed a night technician at the medical examiner’s office with a joint of Thai stick for an autopsy photo, which, unfortunately, never saw the ink of print.

He had beaten the Inquirer to print on a scandal at the police department about a homicide detective who had hounded a man to suicide after the murder of the young man’s parents, a crime of which the young man was innocent.

He’d even had a cover story on a recent adoption scam where a South Philly woman, owner of a shadow agency called Loving Hearts, was taking thousands of dollars for phantom children she never delivered. Although he would have preferred a higher body count in his stories, and grislier photos, he was nominated for an AAN award for “Phantom Hearts,” as that adoption scam piece had been called.

Philadelphia Magazine had also run an exposé on the woman—a full month after Simon’s piece in The Report.

When his stories broke after the paper’s weekly deadline, Simon filed to the paper’s website, which was currently logging nearly ten thousand hits per day.

And so it was when the phone rang around noon, rousing him from a rather vivid dream that included Cate Blanchett, a pair of Velcro handcuffs, and a riding crop, he was suffused with dread at the notion that he might once again have to revisit his Catholic roots.

“Yeah,” Simon managed. His voice sounded like a mile of muddy culvert.

“Get the fuck out of bed.”

There were at least a dozen people he knew who might greet him thusly. It wasn’t even worth firing back. Not this early. He knew who it was: Andrew Chase, his old friend and co-conspirator in journalistic exposé. Although categorizing Andy Chase as a friend was a monumental stretch. The two men tolerated each other the way mold and bread might, a distasteful alliance that, for mutual profit, yielded the occasional benefit. Andy was a boor and a slob and an insufferable prig. And those were his selling points. “It’s the middle of the night,” Simon protested.

“In Bangladesh, maybe.”

Simon wiped the crud from his eyes, yawned, stretched. Close enough to wakefulness. He glanced next to him. Empty.Again. “What’s up?”

“A Catholic school girl was found dead.”

The game, Simon thought.

Again.

On this side of the night, Simon Edward Close was a reporter, and thus the words were a spike of adrenaline in his chest. He was awake now. His heart began that rattle he knew and loved, the noise that meant: story. He rummaged the nightstand, found two empty packs of cigarettes, poked around the ashtray until he hooked a two-inch butt. He straightened it out, fired it, coughed. He reached over, hit record on his trusted Panasonic recorder with its in-line microphone. He had long since abandoned the notion of trying to take coherent notes before his first ristretto of the day. “Talk to me.”

“They found her on Eighth.”

“Where on Eighth?”

“Fifteen hundreds.”

Beirut, Simon thought. This is good. “Who found her?”

“Some wino.”

“On the street?” Simon asked.

“In one of the row houses. In the basement.”

“How old?”

“The house?”

“Jesus, Andy. It’s too fucking early. Don’t muck about. The girl. How old was the girl?”

“Teenager,” Andy said. Andy Chase had been an EMS tech for the Glenwood Ambulance Group for eight years. Glenwood did a lot of the ambulance contract work for the city and, over the years Andy’s tips had led Simon to a number of scoops, as well as to a great deal of inside dope on the cops. Andy never let him forget that fact. This one would cost Simon a lunch at The Plough & The Stars. If the story became a cover story, he owed Andy a hundred extra.

“Black? White? Brown?” Simon asked.

“White.”

Not as good a story as a little white one, Simon thought. Dead little white girls were a guaranteed cover. But the Catholic school angle was great. A load of cheesy similes to cull from. “They take the body yet?”

“Yeah. They just moved it.”

“What the hell was a white Catholic school girl doing on that part of Eighth?”

“Who am I, Oprah? How should I know?”

Simon computed the elements of the story. Drugs. And sex. Had to be. Bread and jam. “How did she die?”

“Not sure.”

“Murder? Suicide? Overdose?”

“Well, the murder police were out there, so it wasn’t an overdose.”

“Was she shot? Stabbed?”

“I think she was mutilated.”

Oh God, yes, Simon thought. “Who’s the primary detective?” “Kevin Byrne.”

Simon’s stomach flipped, did a brief pirouette, then settled. He had a history with Kevin Byrne. The notion that he might lock horns with him again both excited and scared the shit out of him. “Who’s with him, that Purity?”

“Purify. No. Jimmy Purify is in the hospital,” Andy said.

“Hospital? Gunshot?”

“Heart attack.”

Fuck, Simon thought. No drama there. “He’s working alone?”

“No. He’s got a new partner. Jessica something.”

“A woman?” Simon asked.

“No. A guy named Jessica.You sure you’re a reporter?”

“What does she look like?”

“Actually, she’s hot as hell.”

Hot as hell, Simon thought, the excitement of the story heading south from his brain. No offense to female law enforcement officers, but some women on the force tended to look like Mickey Rourke in a pantsuit. “Blonde? Brunette?”

“Brunette. Athletic. Big brown eyes and great legs. Major babe.”

This was shaping up. Two cops, beauty and the beast, dead white girls on crack alley. And he hadn’t lifted cheek one out of bed yet.

“Give me an hour,” Simon said. “Meet me at The Plough.”

Simon hung up, threw his legs over the side of the bed.

He surveyed the landscape of his three-room apartment. What an eyesore, he thought. But, he mused further, it was—like Nick Carraway’s West Egg rental—a small eyesore. One of these days he would hit. He was sure of it. One of these days he would wake up and not be able to see every room of his house from the bed. He would have a downstairs and a yard and a car that didn’t sound like a Ginger Baker drum solo every time he turned it off.

Maybe this was the story that would do it.

Before he could stumble to the kitchen, he was greeted by his cat, a scrappy, one-eared cinnamon tabby named Enid.

“How’s my girl?” Simon tickled her behind her one good ear. Enid curled twice, rolled over on his lap.

“Daddy’s got a hot lead, dolly-doll. No time for loving this morning.”

Enid purred her understanding, jumped to the floor and followed him to the kitchen.

The one spotless appliance in Simon’s entire flat—besides his Apple PowerBook—was his prized Rancilio Silvia espresso machine. It was on a timer to turn on at 9:00 am, even though its owner and chief operator never seemed to make it out of bed before noon. Still, as any coffee fanatic would aver, the key to a perfect espresso is a hot basket.

Simon filled the filter with freshly ground espresso roast, made his first ristretto of the day.

He glanced out his kitchen window into the square airshaft between the buildings. If he bent over, craned his neck to a forty-five-degree angle, pressed his face against the glass, he could see a sliver of sky.

Gray and overcast. Slight drizzle.

British sunshine.

He could just as well be back in the Lake District, he thought. But if he were back in Berwick, he wouldn’t have this juicy story, now, would he?

The espresso machine hissed and rumbled, pouring a perfect shot into his heated demitasse cup, a precise seventeen-second pour, with luscious golden crema.

Simon pulled the cup, savoring the aroma, the start of a glorious new day.

Dead white girls, he mused, sipping the rich brown coffee.

Dead Catholic white girls.

In crack town.

Lovely.

8

MONDAY, 12:50 PM

They split up for lunch. Jessica returned to the Nazarene Academy in a department Taurus. The traffic was light on I-95, but the rain persisted. At the school, she spoke briefly to Dottie Takacs, the school bus driver who picked up the girls in Tessa’s neighborhood. The woman was still terribly upset by the news of Tessa’s death, nearly inconsolable, but she managed to tell Jessica that Tessa was not at the bus stop on Friday morning, and that no, she didn’t recall anyone strange who frequently hung around the bus stop or anywhere along the route. She added that it was her job to keep her eyes on the road.

Sister Veronique informed Jessica that Dr. Parkhurst had taken the afternoon off, but provided her with his home address and phone numbers. She also told her that Tessa’s final class on Thursday had been French II. If Jessica recalled correctly, all Nazarene students were required to take two consecutive years of a foreign language to qualify for graduation. Jessica was not at all surprised that her old French teacher, Claire Stendhal, was still teaching.

She found her in the teachers’ lounge.

...

“Tessa was a wonderful student,” Claire said. “A dream. Excellent grammar, flawless syntax. Her assignments were always handed in on time.”

Talking to Madame Stendhal hurtled Jessica back a dozen years, although she had never been inside the mysterious teachers’ lounge before. Her concept of the room, like that of many of the other students, had been a combination nightclub, motel room, and fully stocked opium den. She was disappointed to discover that, all this time, it was merely a tired, ordinary room with a trio of tables surrounded by chipped cafeteria chairs, a small grouping of love seats, and a pair of dented coffee urns.

Claire Stendhal was another story. There was nothing tired or ordinary about her, never had been: tall and elegant, with to-die-for bone structure and smooth vellum skin. Jessica and her classmates had always been terribly envious of the woman’s wardrobe: Pringle sweaters, Nipon suits, Ferragamo shoes, Burberry coats. Her hair was shocked with silver, a little shorter than she remembered, but Claire Stendhal, now in her midforties, was still a striking woman. Jessica wondered if Madame Stendhal remembered her.

“Did she seem troubled at all lately?” Jessica asked.

“Well, her father’s illness was taking quite a toll on her, as you might expect. I understand she was responsible for taking care of the household. Last year she took nearly three weeks off to care for him. She never missed a single assignment.”

“Do you remember when that was?”

Claire thought for a moment. “If I’m not mistaken, it was right around Thanksgiving.”

“Did you notice any changes about her when she came back?”

Claire glanced out the window, at the rain falling on the commons. “Now that you mention it, I suppose she was a bit more introspective,” she said. “Perhaps a little less willing to engage in group discussion.”

“Did the quality of her work decline?”

“Not at all. If anything, she was even more conscientious.”

“Was she close friends with anyone in her class?”

“Tessa was a polite and courteous young woman, but I don’t think she had many close friends. I could ask around, if you like.”

“I would appreciate it,” Jessica said. She handed Claire a business card. Claire looked at it briefly, then slipped it into her purse, a slim Vuitton Honfleur clutch. Naturellement.

“She talked about going to France one day,” Claire said.

Jessica remembered talking about the same thing. They all did. She didn’t know a single girl in her class who had actually gone.

“But Tessa wasn’t one of those who mooned about romantic walks along the Seine, or shopping on the Champs-Elysées,” Claire continued. “She talked about working with underprivileged kids.”

Jessica made a few notes about this, although she was not at all sure why. “Did she ever confide in you about her personal life? About someone who might have been bothering her?”

“No,” Claire said. “But not all that much has changed since your high school days in that regard. Nor mine, for that matter. We are adults, and the students see us that way. They really are no more likely to confide in us than they are in their parents.”

Jessica wanted to ask Claire about Brian Parkhurst, but it was only a hunch she had. She decided not to. “Can you think of anything else that might help?”

Claire gave it a few moments. “Nothing comes to mind,” she said. “I’m sorry.”

“That’s quite all right,” Jessica said. “You’ve been very helpful.”

“It’s just hard to believe that...that’s she’s gone,” Claire said. “She was so young.”

Jessica had been thinking the same thing all day. She had no response now. None that would comfort or suffice. She gathered her belongings, glanced at her watch. She had to get back to North Philly.

“Late for something?” Claire asked. Wry and dry. Jessica recalled the tone quite well.

Jessica smiled. Claire Stendhal did remember her.Young Jessica had always been tardy. “Looks like I’m going to miss lunch.”

“Why not grab a sandwich in the cafeteria?”

Jessica thought about it. Perhaps it was a good idea. When she was in high school she was one of those weird kids who actually liked cafeteria food. She hiked her courage and asked: “Qu’ est-ce que vous . . . proposez?”

If she wasn’t mistaken—and she desperately hoped she wasn’t—she had asked: What do you suggest?

The look on her former French teacher’s face told her she got it right. Or close enough for high school French.

“Not bad, Mademoiselle Giovanni,” Claire said with a generous smile.

“Merci.”

“Avec plaisir,” Claire replied. “And the sloppy joes are still pretty good.”

Tessa’s locker was only six units away from Jessica’s old one. For a brief moment, Jessica was tempted to see if her old combination still worked.

When she had attended Nazarene, Tessa’s locker belonged to Janet Stefani, the editor of the school’s alternative newspaper and resident pothead. Jessica half expected to see a red plastic bong and a stash of Ho Hos when she opened the locker door. Instead she saw a reflection of Tessa Wells’s last day of school, her life as she left it.

There was a Nazarene hooded sweatshirt on a hanger, along with what looked like a home-knit scarf. A plastic rain bonnet hung from the hook. On the top shelf, Tessa’s gym clothes were clean and neatly folded. Beneath them was a short stack of sheet music. Inside the door, where most girls kept a collage of pictures, Tessa had a cat calendar. The previous months had been torn out. The days had been crossed off, right through the previous Thursday.

Jessica checked the books in the locker against Tessa’s class list, which she had gotten from the front office. Two books were missing. Biology and algebra II.

Where were they? Jessica wondered.

Jessica riffled the pages of Tessa’s remaining textbooks. Her communications media textbook offered a class syllabus on hot pink paper. Inside her theology text—Understanding Catholic Christianity—there was a pair of dry-cleaning coupons. The rest of the books were empty. No personal notes, no letters, no photographs.

At the bottom of the locker were a pair of calf-high rubber boots. Jessica was just about to close the locker when she decided to pick up the boots and turn them over. The left boot was empty. When she turned over the right boot, an item tumbled out and onto the highly polished hardwood floor.

A small, calfskin diary with gold leaf trim.

...

In the parking lot Jessica ate her sloppy joe and read from Tessa’s diary.

The entries were sparse, with days between notations, sometimes weeks. Apparently, Tessa wasn’t someone who felt compelled to commit every thought, every feeling, every emotion and interaction to her journal.

On the whole, she seemed a sad girl, seeing the poignant side of life as a rule. There were entries about a documentary she had seen on three young men whom, she believed, as did the filmmakers, were falsely convicted of murder in West Memphis, Tennessee. There was a long entry about the plight of hungry children in Appalachia. Tessa had donated twenty dollars to the Second Harvest program. There were a handful of entries about Sean Brennan.

What did I do wrong? Why won’t you call?

There was one long, rather touching story about a homeless woman Tessa had met. A woman named Carla who lived in a car on Thirteenth Street. Tessa did not say how she’d met the woman, only how beautiful Carla was, how she might have been a model if life had not taken so many bad turns for her. The woman told Tessa that one of the worst parts of living out of a car was that there was no privacy, that she lived in constant fear that someone was watching her, someone intent on doing her harm. Over the following few weeks, Tessa thought long and hard about the problem, then realized there was something she could do to help.

Tessa paid a visit to her aunt Georgia. She borrowed her aunt’s Singer sewing machine and, at her own expense, made curtains for the homeless woman, drapes that could be cleverly hooked into the fabric of the car’s interior ceiling.

This was a special young lady, Jessica thought.

The last entry of note read:

Dad is very sick. He is getting worse, I think. He tries to be strong, but I know it is just an act for me. I look at his frail hands and I think about the times, when I was small, when he would push me on the swings. I felt as if my feet could touch the clouds! His hands are cut and scarred from all the sharp slate and coal. His fingernails are blunt from the iron chutes. He always said that he left his soul in Carbon County, but his heart is with me.And with Mom. I hear his terrible breathing every night. Even though I know how much it hurts, each breath comforts me, tells me he is still here. Still Dad.

Near the center of the diary, there were two pages torn out, then the very last entry, dated nearly five months earlier, read, simply:

I’m back. Just call me Sylvia.

Who is Sylvia? Jessica wondered.

Jessica went through her notes. Tessa’s mother’s name was Anne. She had no sisters. There was certainly no “Sister Sylvia” at Nazarene.

She flipped back through the diary. A few pages before the section that was removed was a quote from a poem that she didn’t recognize.

Jessica turned once again to the final entry. It was dated right around Thanksgiving of the previous year.

I’m back. Just call me Sylvia. Back from where, Tessa? And who is Sylvia?