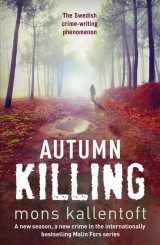

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

16

Borje Svard is standing in the rain in his garden in Tornhagen wearing a light blue raincoat. From the car Malin sees him raise his hand and throw a stick between the apple trees down towards the red-painted kennel block. The two beautiful Alsatians’ coats are glistening with damp as they chase the stick, playfully fighting over it with sharp, bared teeth.

Borje is a thickset man, and his waxed moustache is drooping towards the grass.

Zeke stops in front of the gate, parking behind the blue car of a district nurse. In the back seat Jerry Petersson’s beagle has leaped up, not barking, just staring expectantly out at the dogs in the garden.

Borje looks over towards them. Waves them over to him, stays where he is in the middle of the garden.

The little single-storey house is painted white, well maintained. Borje’s wife Anna would never tolerate anything else, even though she’s so weak now that she can’t even breathe without help. The illness has destroyed the nerves around her lungs and she’s living on overtime, at the age of fifty.

They leave Jerry Petersson’s dog in the car, and the Alsatians rush over to them as they open the gate.

Not wary, but welcoming, sniffing and licking, before they set off down the garden again without paying any attention to the beagle in the back seat.

Zeke and Malin go over to Borje. Shake his wet hand.

‘How are you both doing?’ Zeke asks.

Borje shakes his head, turns away from the house.

‘I wouldn’t wish what she’s going through on anyone.’

‘That bad?’ Malin says.

‘The nurses are with her now. They come four times a day. Otherwise we manage by ourselves.’

‘Would she like to see us, do you think?’

‘No,’ Borje says. ‘She hardly wants to see me. I see you’ve got a dog in the car? I can’t imagine it’s yours, Fors?’

Malin explains what’s happened, who the dog belonged to, and would he mind looking after it for a while, until they know if there’s a relative or someone else who wants it?

Borje smiles. A smile that gradually breaks through layer upon layer of exhaustion, of grief experienced in advance.

‘A bitch?’

‘No. Male,’ Zeke says.

‘That might be OK,’ Borje replies, then he goes over to the car and the dog bounces about in the back seat, and a couple of minutes later it’s standing to attention beside Borje while the Alsatians sniff all around it.

‘Looks like he feels at home here,’ Malin says. ‘Nice and easy.’

‘Get back to work, I’ll look after the dog. What’s his name?’

‘No idea,’ Malin replies. ‘Maybe you could call him Jerry?’

‘That would just confuse him,’ Borje replies.

‘We’d better get going,’ Zeke says.

Borje nods.

‘I appreciate you dropping by.’

‘Look after yourselves,’ Malin says, then turns away.

The call comes at exactly a quarter past two, as Malin and Zeke are parking the car at the old bus station. There’s not much left of the buildings that stood on the square years ago. Now there’s a car park surrounded by buildings from different eras. Ugly grey-panelled blocks from the sixties, well-maintained buildings from the turn of the last century, with the skeletal black trees of the Horticultural Society Park in the background.

Close to Mum and Dad’s flat now. The damp, dark rooms that no one has lived in for years. The flat is pretentiously large, but it still isn’t a proper apartment. Why have they still got it? So Mum can tell her friends in Tenerife that they’ve got an apartment in the city? Their faces are starting to fade from my memory, Malin thinks as her mobile rings again. Mum’s thin cheeks and pointed nose, Dad’s laughter lines and oddly smooth forehead.

A silent love, theirs. An agreement. Like mine and Janne’s? A lingering love, clinging to the back of our memories, in a room to which we haven’t yet managed to close the door.

The plants they think are still alive.

Dried out.

Not a single damn plant alive any more, but what do they expect when they haven’t been home for more than two years?

She pulls her mobile from the pocket of the GORE-TEX jacket.

Hears the rain drumming on the roof of the car. Zeke wary beside her.

Tove’s number on the screen.

What can I say to her? Is she going to be sad, scared?

How can I talk to her without Zeke realising?

He’ll realise. He knows me too well.

‘Tove, hi. I saw you rang earlier.’

Silence at the other end.

‘I know it all ended weirdly yesterday and I should have called back, but something’s happened and I’ve been busy at work. Is Dad there?’

I hit him, Malin thinks. I hit him.

‘I’m at school,’ she finally hears Tove’s voice say. She’s not sad, not scared, almost sounds angry. ‘If you need to talk to Dad, call him.’

‘Of course, you’re at school. I’ll give him a call if I need to talk to him. Why don’t you come into the city this evening and we’ll have something to eat, OK?’

Tove sighs.

‘I’m going to go back to the house, to Dad.’

‘You’re going back to Dad.’

‘Yes.’

Another silence. It’s as if Tove wants to ask something, but what?

‘Well, you do whatever you want, Tove,’ Malin says, and she knows it’s exactly what she shouldn’t say, she ought to say things like: It’s all going to be OK, I’ll pick you up from school, I want to give you a big hug, I’ll make an effort, how are you, my darling daughter?

‘How are you, Mum?’

‘How am I?’

‘Forget it. I’ve got to go. I’ve got a lesson.’

‘OK, bye then. Talk to you later. Big kiss.’

Zeke looking at her sympathetically. He knows everything, absolutely everything.

‘So you’re living back in the city again? I wondered when I picked you up this morning.’

‘It’s nice to be home.’

‘Don’t be so hard on yourself, Malin. We’re only human.’

Tove clicks to end the call and watches her schoolmates hurrying to and fro along the corridor of the Folkunga School, sees the way the high ceiling and the dark light filtering in through the arched windows from the rain-drenched world outside makes the pupils look smaller, defenceless.

Bloody Mum.

The least she could have done is call back. She doesn’t even seem to be considering coming back to the house tonight. Now the pain in her stomach is growing again, below her heart, growing impossibly large. She sounded abrupt and businesslike, it was as if she wanted to finish the call as soon as possible, she didn’t even ask how I am, why did I even bother to call? She probably just wants to go and have a drink.

I know why I called.

I want her to come home. I want them to stand in the kitchen having a hug, and I want to watch.

Don’t think about it, Tove.

She taps her mobile against her head.

Don’t think about it.

Some twenty metres away three of the older boys are grouped around a fat younger boy. Tove knows who he is. An Iraqi who can hardly speak a word of Swedish, and the older boys love bullying him. Bloody cowards.

She feels like getting up, going over and telling them to stop. But they’re bigger, much bigger than her.

Mum sounded disappointed when she said she was going back to Dad’s. Tove had been hoping that would make her want to go as well, but deep down she knows that’s not how things work in the adult world, everything’s so damn complicated there.

Now they’re hitting the boy.

Abbas, that’s his name.

And she puts her pen and notepad on the floor by her locker. She pushes her way through the crowd over to the three bullies. She shoves the tallest of them in the back, yelling: ‘Why don’t you pick on someone your own size instead?’ and Abbas is crying now, she can see that, and the force of her voice must have surprised the stupid bloody idiots, scared them, because they back away, staring at her. ‘Get lost,’ she yells, and they stare at her as if she’s a dangerous animal, and Tove realises why she frightens them, they must know what happened out in Finspang, what happened to her, and they respect her because of that.

Idiots, she thinks. Then she puts her arms around Abbas, he’s small and his body is soft, and she pretends he’s Mum, that she can comfort her with just a hug and a promise that everything’s going to be all right, from now on everything’s going to be all right.

Axel Fagelsjo’s apartment on Drottninggatan is, to put it in estate-agent jargon, magnificently appointed, Malin thinks. But it’s still only a fraction as ostentatious as Skogsa Castle.

Panelling, and shiny, tightly woven Oriental rugs that make her headache flare up again. Authentic, expensive, quite different from the cheap rugs bought at auction on the floors of her mum and dad’s flat. The worn leather of the armchairs shimmers in the light of the chandeliers and candelabra.

And the man in front of them.

He must be about seventy, Malin thinks. And right-handed. The embodiment of authority, and she tries to stay calm, not become defensive the way she knows she always is when she meets people higher up the social ladder than she could ever get.

All of this still exists.

The Social Democrats may have managed to create a superficial equality in this country for a while, but it’s thin and transparent and false.

Portraits of Count Axel Fagelsjo’s ancestors hang in a row above the panelling. Powerful men with sharp eyes. Warriors, many of them.

They are witness to Fagelsjo’s awareness that he’s better than the rest of us, worth more. Unless that’s just my own prejudice? Malin thinks.

There are still big differences between people in Sweden. Bigger than ever, perhaps, because there’s a professed political desire to create a blue sheen of equality, a mendacious glow, as if there’s still a green shimmer of cash casting a light over the lives of the poor.

The blues say we’re all equally valuable. That everyone should have the same opportunities. And then they repeat it. And it becomes a truth even if they implement policies that mean those with money in the bank keep on getting richer even in these troubled times.

The whole of society is tainted with lies, Malin thinks.

And those lies give rise to a feeling of being fooled, denied and rejected.

Maybe that’s how I feel, deep down, Malin thinks. Trampled on, without actually realising it.

Voiceless by nature.

And if you have neither words nor anyone’s ear, that’s when violence is born. I’ve seen it happen a thousand times.

Malin looks at the portraits in Fagelsjo’s sitting room, then at the stout, ruddy-cheeked count with the self-confident smile that has suddenly appeared.

New money, like Petersson’s. Old money, like Fagelsjo’s. Is there really any difference? And what on earth are inherited privileges doing in a modern society?

‘Thank you for seeing us,’ Malin says as she sits down on a ridiculously comfortable leather armchair, and Axel Fagelsjo stubs out his cigarette.

Fagelsjo smiles again, his smile is properly friendly now, he means us well, Malin thinks, but with all his privileges, he can probably afford to?

‘Of course I’m happy to see you. I understand why you’re here. I heard on the radio about Petersson, and it was only a matter of time before you came to see me.’

Zeke, sitting beside Malin, wary, evidently also affected by the old count’s presence.

‘Yes, we have reason to believe that he was murdered. So naturally that raises a number of questions,’ Zeke says.

‘I’m at your disposal.’

Fagelsjo leans forward, as if to demonstrate his interest.

‘To begin with,’ Malin says, ‘what were you doing last night and this morning?’

‘I was drinking tea with my daughter Katarina yesterday evening. Then, at ten o’clock, I came home.’

‘And after that?’

‘I was at home, as I said.’

‘Is there anyone who can confirm that?’

‘I’ve lived alone since my wife died.’

‘There are rumours,’ Zeke says, ‘that the family hit hard times and that was why you were forced to sell Skogsa to Petersson.’

‘And who would spread rumours like that?’

Fagelsjo’s eyes flashing with sudden anger, but nonetheless feigned anger, Malin thinks: no point trying to hide what everyone knows.

‘I can’t tell you that,’ Zeke says.

‘They’re just rumours,’ Fagelsjo says. ‘What they wrote in the Correspondent was nonsense. We sold the castle because it was time, it had served its role as the family seat. These are new times. Time had simply caught up with our way of life. Fredrik works for the Ostgota Bank, Katarina works in art. They don’t want to be farmers.’

You’re lying, Malin thinks. Then she thinks of her recent conversation with Tove, and feels sick at how, against her will, she had treated it like a work conversation, how she couldn’t break through and say the things that needed saying. How could you, Fors? How could anyone?

‘So there were no arguments?’ she goes on. ‘No disagreements?’

Fagelsjo doesn’t answer, and says instead: ‘I never met Petersson in relation to the sale. Our solicitors handled that, but I got the impression that he was one of those businessmen who want nothing more than to live in a castle. I daresay he had no idea of the work that requires, regardless of the amount of money one has to hire people to do it.’

‘He paid well?’

‘I can’t tell you that.’

Fagelsjo smiles at his own words, and Malin can’t tell if he’s being consciously ironic and mimicking Zeke’s words or not.

‘I have difficulty seeing what significance the amount might have for your investigation.’

Malin nods. They can find out the amount, if it proves to be important.

‘Had you passed the castle on to your son?’

‘No. The castle was still in my ownership.’

‘The sale must have been upsetting for you,’ Malin says. ‘After all, your ancestors had lived there for centuries.’

‘It was time, Inspector Fors. That’s all there was to it.’

‘And your children? Did they react badly to the sale?’

‘Not at all. I daresay they were happy about the money. I tried to find a place for the children at the castle, but it didn’t suit them.’

‘A place?’

‘Yes, let one of them take over the running of it, but they weren’t interested.’

‘Are you happy here?’ Zeke asks, looking around at the spacious apartment.

‘Yes, I’m happy here. I’ve lived here since the sale. In fact, I’m so happy here that I’d like to be alone now, if you have no more questions.’

‘What sort of car do you drive?’

‘I have two. A black Mercedes and a red Toyota SUV.’

‘That’s all for now,’ Zeke says, getting up. ‘Do you know where we can find your children?’

‘I presume you have their telephone numbers. Call them. I don’t know where they are.’

In the hall Malin notices a pair of black rubber boots. The mud on them is still wet.

‘Have you been out in the forest?’ she asks Fagelsjo, who has followed them to the door.

‘No, just down to the Horticultural Society Park. That’s quite muddy enough for me at this time of year.’

When the front door has closed Fagelsjo goes down the corridor towards the kitchen.

He picks up the phone. Dials a number that he has managed to memorise with great difficulty.

Waits for an answer.

Thinks about the instructions that need to be given, how abundantly clear he will need to be for the children to understand. Thinks: Bettina. I wish you were here now. So we could deal with this together.

‘The best of both worlds,’ Zeke says as they head back to the car.

‘Sorry?’

‘He lives, or would like to live, in the best of both worlds.’

‘He’s lying to us about the sale, that much is obvious. I wonder why? I mean, it’s common knowledge that they’d fallen on hard times. It was in the Correspondent.’

Zeke nods. ‘Did you see how he clenched his fists when you asked about the sale? It looked like he could hardly keep his anger under control.’

‘Yes, I saw,’ Malin says, opening the passenger door of the car and thinking about the feeling she had that Fagelsjo was only pretending to be angry. Why? she asks herself.

‘We need to dig deeper,’ Zeke says, looking at Malin, who looks as if she’s about to fall asleep, or start screaming for a drink.

I’ve got to talk to Sven. She’s gone right under the ice this time.

‘Let’s hope that’s exactly what Ekenberg and Johan are doing right now, digging deeper.’

‘And Karim must be basking in the glow of the flashbulbs as we speak,’ Zeke says.

17

Karim Akbar is absorbing the flashbulbs, his brain whirring as the reporters fire off their aggressive questions.

‘Yes, he was murdered. By a blow from a blunt object to the back of the head. And in all likelihood he was also stabbed in the torso.’

‘No, we don’t have the object. Nor the knife.’

‘We’ve got divers in the moat right now,’ he lies. The diving is already finished. ‘We may need to drain it,’ he says. The water is probably gone by now. His massaging of the truth is silly really, the reporters can easily check the moat, but Karim can’t help it, wants to show the hyenas who decides the speed they go at.

‘At present we don’t have a suspect. We’re looking into a range of possibilities.’

The crowd of grey figures before him, most of them shabbily dressed, in line with all the cliches about journalists.

Daniel Hogfeldt an exception. Smart leather jacket, a neatly ironed black shirt.

Karim can answer questions and think about other things at the same time, he’s done this so many times before.

Is that when it’s time to stop?

When autopilot kicks in?

When you start to mess about with the seriousness of the situation?

He can see himself standing in the room, like a well-drilled press officer in the White House, pointing at reporters, answering their questions evasively, all the while getting his own agenda across.

‘Yes, you’re right. There could be a number of people with reason to be unhappy with Jerry Petersson’s activities. We’re looking into that.’

‘And Goldman, have you spoken. .’

‘We’re keeping all our options open at present.’

‘We’re appealing to members of the public who may have seen anything interesting that night between. .’

Waldemar Ekenberg is leaning over the table in their strategy room, reading one of the files about Jochen Goldman.

Johan Jakobsson is slumped on the other side of the table, next to an IT expert who’s installing a monitor.

‘There’s an address and a phone number here. Vistamar 34. Belongs to a J.G.,’ Waldemar says.

‘Must be Jochen Goldman.’

‘This is from this year.’

‘What’s the context?’

‘Figures, some company.’

‘What’s the international dialling code?’

‘Thirty-four.’

‘That could be Tenerife, if he does live there. Vistamar. Definitely Spanish. Shall I call?’

‘Well, we want to talk to him.’

Johan leans back, reaching for the phone, makes the call.

‘No answer, but at least it rang. Doesn’t seem to have an answer machine.’

‘Did you expect him to? We’ll try again later.’

‘Malin’s parents live on Tenerife,’ Johan says.

‘Fucking hot down there.’

‘Maybe we should get Malin to make the call.’

‘What, you mean she should make the call because her parents live down there?’

Johan shakes his head.

‘Well, you’re getting to know her a bit now. She might get upset otherwise. She takes coincidences like that seriously.’

‘Yeah, she believes in ghosts,’ Waldemar says.

‘Hold off from making the call. Let her do it. If it is even Jochen Goldman’s number.’

Waldemar shuts the file.

‘I don’t get most of these figures. When’s the bloke from Eco getting here?’

An officer, they don’t yet know who, is supposed to be coming down by train the next day.

‘Tomorrow morning,’ Johan says.

Waldemar nods.

The Ostgota Bank at the corner of Storgatan and St Larsgatan. Just a stone’s throw from Malin’s flat on Agatan, but the two buildings couldn’t be more different. Malin’s block is late modern, from the sixties, low ceilings with plastic window frames installed in the mid-seventies. The Ostgota Bank is a showy art nouveau building in brown stone with an ornate interior.

But the rain is the same for all buildings, Malin thinks as she pulls open the heavy door and steps into the large foyer, all polished marble and a ten-metre high ceiling. The reception desk for the offices upstairs is to the left of the cashiers, who are scarcely visible behind thick bullet-proof glass.

Malin and Zeke have called Fredrik Fagelsjo’s mobile, but there was no answer. They tried him at home, no answer there either.

‘Let’s go to the bank and see if he’s there,’ Malin had said as they drove away from Axel Fagelsjo’s apartment, and now a red-haired, hostile-looking receptionist the same age as Malin is staring at her police ID.

‘Yes, he works here,’ the receptionist says.

‘Can we see him?’ Malin asks.

‘No.’

‘I see. We’re here on important police business. Is Fredrik Fagelsjo. .?’

‘You’re too late,’ the receptionist says neutrally, with a hint of triumph in her voice.

‘Has he finished for the day?’ Zeke asks.

‘He usually leaves at three on Friday. What’s this about?’

Never you mind about that, Malin thinks, saying: ‘Do you know where he might have gone?’

‘Try the Hotel Ekoxen. He’s normally in the bar there after work on Fridays.’

‘Friday beer?’

‘More like Friday cognac,’ the receptionist says with a warm smile.

‘Can you describe him to us? So we know who we’re looking for?’

A moment later Malin is holding the bank’s annual report in her hand. The glossy, smooth, dark-blue paper feels as if it’s going to wear a hole in the palm of her hand.

The Ekoxen.

One of the smartest hotels in the city.

Maybe the smartest of all, situated between the Tinnerback swimming pool and the Horticultural Society Park, a white-plastered building that looks like a sugar lump. The hotel’s piano bar has a view across the pool and is one of the most popular watering holes in the city. But not for me, Malin thinks. Way too far up its own fucking arse.

They roll slowly down Klostergatan towards the hotel through restrained yet persistent rain. She’s holding the photograph in the annual report in front of her. To judge by the picture, Fredrik Fagelsjo is about forty. His face is thin, dominated by a narrow, straight nose and a pair of anxious green eyes. He’s thin, unlike his father, and the blue blazer he’s wearing in the picture looks new. His shoulders are hunched, almost as if he’s afraid of falling, and there’s something evasive and hunted about his whole bearing.

Zeke pulls up in front of the entrance to the hotel. In the rear-view mirror Malin sees a side door open and someone steps out.

Fredrik Fagelsjo.

Is that you? Have you finished your Friday cognac?

‘I think Fagelsjo just left through the back door.’

A black Volvo is parked right outside the other door, and before Malin and Zeke have time to react, the man they think is Fredrik has got in the car and driven off in the opposite direction to them.

‘Shit,’ Malin says. ‘Turn around.’

And Zeke spins the wheel, but at that moment a lorry turns into the road from the other direction and stops.

‘Fuck.’

‘I’ll try his mobile again.’

The lorry reverses out of their way and Zeke pulls onto the other side of the road and accelerates hard, and they head down towards Hamngatan at high speed, overtaking a rusty white Volkswagen.

‘He’s not answering,’ Malin says as they turn into Hamngatan. ‘I can see him,’ she says. ‘He’s stuck at a red light by McDonald’s.’

No flashing lights, Malin thinks, no sirens. Just pull up alongside and wave him over, all according to the rulebook. After all, we only want to talk to him.

Zeke puts his foot down and they pull up alongside what they think is Fredrik Fagelsjo’s car before the lights change. Hungry teenagers inside McDonald’s. People defying the worsening rain and crossing the square in the background.

Zeke blows the horn and Malin holds her police ID up to the window. Fredrik Fagelsjo, there’s no doubt that it’s him, looks at Malin, at her ID, and his face takes on a look of panic when Malin gestures that he should pull over and wait for them outside McDonald’s.

Fagelsjo nods, then looks straight ahead, and seems to put his entire weight on the accelerator pedal, and his Volvo shoots away as the lights go amber, pulling in ahead of them and burning off along Drottninggatan.

Shit, Malin manages to think. Yells: ‘He’s making a run for it. The bastard’s making a run for it!’

And Zeke spins the wheel and heads off after Fagelsjo along Drottninggatan, while Malin winds down the window and sticks the flashing light on the roof of the car.

‘What the hell?’ Zeke shouts. ‘Let command know over the radio. Get them to send more cars if we’ve got any.’

Malin stays quiet, wants to let Zeke concentrate on driving, as Fredrik flashes past the orange building that once housed the National Bank at what must be a hundred kilometres an hour, heading towards the Abis roundabout, past the old specialist food store.

What the hell is this? Malin thinks. Are you a panic-stricken murderer? Why the hell are you running from us?

A hundred metres ahead of them Malin sees some pedestrians throw themselves out of the way as Fagelsjo runs a red light. She feels the adrenalin pumping as she shouts instructions over the radio.

‘Driver refusing to stop. We’re following a black. . out towards the Berg roundabout, all available cars. .’

Zeke swerves past a few cars that have ended up between them and Fagelsjo, and their speed, one hundred and twenty now, in the middle of the city, makes Malin feel that the world as she knows it is dissolving into crazy lines and colours, and she feels violently sick now, her headache throbbing, but soon the adrenalin takes over again and the present becomes clear and focused.

‘He’s turning off past Ikea, out towards Vreta Kloster,’ Malin yells, and the sound of the racing engine blends with the siren in a strangely exciting symphony.

Fagelsjo drives past Ikea’s Tornby store, his car weaving as though he were drunk.

Maybe he is drunk, Malin thinks. He came out of the Ekoxen. She feels her nausea take hold of her stomach again, she feels like throwing up, but the adrenalin forces her stomach back down.

Zeke takes one hand off the wheel and presses the CD player, and German choral music, something from a Wagner opera, blasts through the car.

‘What the fuck?’ Malin yells.

‘It makes me drive better,’ Zeke grins.

Fagelsjo is lucky with the lights as he heads across the roundabout on the E4. They pass the last blocks of flats in Skaggetorp and are out in the country, surrounded by empty fields and small farms huddled down against the wind.

The message from control is scarcely audible over the voices of the choir.

‘Fredrik Fagelsjo lives out on the plain, off left from Ledberg. He could be heading home.’

He’s pulling away, Malin thinks. ‘Step on it!’ she yells. Could we really be getting somewhere? Did Fredrik Fagelsjo kill Jerry Petersson? Is that why he’s running?

A patrol car drives up alongside, but Zeke gestures to it to pull back, and when they reach the Ledberg junction Fagelsjo lurches left but manages to straighten the car out and continue at an ever-increasing speed out towards a small cluster of houses surrounded by thin trees, maybe two kilometres further out on the plain in the direction of Lake Roxen.

Zeke’s forehead is sweating. Malin can feel him taking shallow, stressed breaths, and she pulls her pistol from its holster as the road curves towards the group of houses. A large brick villa, painted yellow, in a clump of trees. A proper upper-class mansion, and, a hundred metres further on, Fagelsjo swings off again, down a driveway.

They follow him, and, seventy metres in front of them he has stopped in front of a crooked red-painted barn surrounded by bare bushes and maples. He leaps out of the car and runs over into the barn.

Zeke pulls up behind Fagelsjo’s car and the patrol car stops just behind them. Malin turns off the CD and the siren, and everything is suddenly strangely quiet.

Over the radio Malin says quietly: ‘Get out and cover us when we follow him inside the barn.’

The gravel and mud outside the barn sticks to their shoes. Malin looks towards the building, feels the rain getting harder as they walk the few metres from the car to the barn door. Behind them is the villa, built in the Italian style, presumably Fagelsjo’s home. If he’s got a family, they don’t seem to be in. The two uniforms have taken out their Sig Sauers, taking cover behind the car doors, ready to open fire if anything goes wrong.

Zeke beside her, both of them holding their pistols in front of them as Malin kicks open the door of the barn and shouts: ‘Fredrik Fagelsjo. We know you’re in there. Come out. We just want to talk to you.’

Silence.

Not a sound from the manure-stinking building.

Trying to run, Malin thinks, would be the most stupid thing you could do. Where would you go? Goldman. He stayed on the run for ten years. So it is possible. But you’re hiding in there, aren’t you? Waiting for us. You might be armed. People like you always have at least a hunting rifle. Are you waiting for us with a gun?

Talking to herself like that helps her stay focused, and stops the fear from taking over. Into the darkness now, Malin. Whatever’s waiting inside.

‘I’ll go first,’ Zeke says, and Malin is grateful. Zeke never backs down when it comes to the crunch.

He steps inside the barn and Malin follows him. Black and dark, with a smell of fresh manure and some other indefinable animal waste. There’s light from one corner, opening onto a field, Zeke runs towards it and Malin follows.

‘Shit,’ Zeke yells. ‘He must have gone straight through.’

They rush over to the open door.

Some hundred metres away, down in the field, through the rain and fog, Fagelsjo is running, dressed in brown trousers and what must be a green oilskin. He stumbles and gets up, runs a bit further, past a tree that’s still got a few leaves.

‘Stop!’ Malin shouts. ‘Stop, or I’ll shoot.’

Which she wouldn’t do. They’ve got nothing on Fagelsjo, and running from the police isn’t sufficient justification for firing.

But it’s as if all the air goes out of him. He stops, turns around, raises his empty hands and looks at her and Zeke, who are slowly approaching him, weapons drawn.

He’s swaying back and forth.

You’re drunk, Malin thinks, then shouts: ‘Lie down. Lie down.’

And Fredrik Fagelsjo lies down on his stomach in the mud as Malin puts a pair of handcuffs on his wrists behind his back. A filthy, green, classic Barbour jacket.

He stinks of alcohol, but says nothing, maybe he can’t talk with his face on the ground.

‘What the hell was all that in aid of?’ Malin says, but Fagelsjo doesn’t reply.