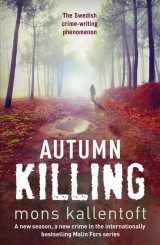

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

49

Friday, 31 October

The solicitor, Johan Stekanger, speeds up and puts the windscreen wipers on full, and they flap like hens with their necks wrung over the windscreen in front of him.

The Jaguar responds to his commands and they glide past the bus in plenty of time to avoid a sad black Volvo estate.

The heated seat is warming his arse agreeably. It’s particularly rough outside at this time of the morning. The car still smells new and fresh, of chemicals, and the grey interior undoubtedly matches the season.

The art on the walls of the castle, every wall covered by pictures that don’t seem to be of anything at all, but which he understands are worth a great deal.

Hence the idiot in the tweed suit in the seat next to him, a Paul Boglover, sorry, Boglov, an expert in contemporary art, down from Stockholm to document and value Jerry Petersson’s art collection.

Boglov is presumably hoping he’ll get the chance to sell the rubbish, Johan Stekanger thinks as they pull up in front of the castle, beyond the bridge over the now empty moat.

He hasn’t said much.

Maybe he’s picked up on my dislike of him, Johan Stekanger wonders. That was actually one of the reasons why he moved back to Linkoping after studying in Stockholm. The people here were more homogenous, and you hardly ever saw any queers on the city’s well-kept streets. He’s always had trouble with queers.

The clock on the dashboard says 10.12.

An estate inventory of the most grandiose variety, the largest he’s ever dealt with. There’ll be a hefty fee at the end of it, that much is beyond question.

So it was worth putting up with an art-loving queer from the queer metropolis.

He can’t stand me, Paul Boglov thinks, as the ill-mannered solicitor in the cheap green suit and the blond hair hanging down over his collar taps the code into the alarm panel beside the main door of the castle.

But why should I care what he thinks?

Backwoods bigot.

‘Well, welcome to the splendour of Skogsa.’

‘Bloody hell!’

The words are out of Paul Boglov’s mouth before he can stop them, and when he finally manages to tear his eyes from the enormous painting on the wall of the entrance hall, he sees the philistine solicitor beside him grinning.

‘Really? Valuable?’

‘It’s a Cecilia Edefalk. From her most famous series.’

‘Doesn’t look like much if you ask me. A man rubbing suncream on a woman’s back. I mean, he could have rubbed it onto her front!’

I’m not going to respond to that, Paul Boglov thinks.

Instead he takes out his camera, photographs the painting, and makes some notes in his little black book.

‘There’s stuff like that in almost every room.’

Paul Boglov goes from room to room, taking photographs, doing calculations, and reacting with childish surprise, and with each room the feeling of making a great discovery grows within him. Was this what it felt like when they discovered the Terracotta Army in China?

Mamma Andersson, Annika von Hausswolff, Bjarne Melgaard, Torsten Andersson, a fine Maria Meisenberger, Martin Wickstrom, Clay Ketter, Ulf Rollof, a Tony Oursler head with the lights switched off.

Impeccable taste. Contemporary. Must have been bought during the last decade.

Did Jerry Petersson choose the works himself?

A feeling for quality. That’s something you’re born with.

And the philistine.

His idiotic comments.

‘Looks like an ordinary photograph if you ask me.’

About the little Meisenberger.

‘A bit of glass with holes in.’

About the Ulf Rollof above the bed in what must have been Jerry Petersson’s master bedroom.

Art worth thirty million kronor. At least.

Almost all the rooms have been checked when Paul Boglov gets a glass of water in the kitchen and reads through his notes, checking the pictures of the works in his camera.

It’s all in the eye.

Petersson, or someone else, must have had a perfect eye for art.

You’re moving through my rooms.

You gawping, him mocking.

You don’t know what you’re about to find, what I’ve just seen.

There’s a reason I was drawn to art, that much is true.

But I’m not going to talk about that now, Malin Fors will have to guess her way to it.

I was overwhelmed by art. I got so much more out of it than I expected. At first I couldn’t afford it, but it didn’t take long.

In my pictures I saw, I see, all the feelings I don’t have names for. Just look at the perforated glass above my bed. At the beauty and pain in it. Or at Melgaard’s fist-fucking monkeys, their poorly disguised terror at what they are, what they have become, the love they left behind somewhere.

Or at Maria Meisenberger’s empty human shadows. Like sins you can never leave behind.

‘There’s a chapel as well,’ the philistine says. ‘It’s got some Jesus pictures in gold. Do you want to see them?’

Icons, Paul Boglov thinks. He doesn’t even know they’re called icons, but he can’t mean anything else, can he?

‘Where’s the chapel?’

‘Behind the castle, down by the forest.’

Paul Boglov puts his glass down on the draining board.

Outside the Lord of Rain is in full command, the day dark even though it is only just midday.

They walk quickly around the castle. The chapel is located alone and abandoned on the edge of a dense forest of fir trees.

A key in the philistine’s hand.

Icons, Paul Boglov thinks. I wonder if Jerry Petersson had as much taste when it came to them?

‘Looks like it’s unlocked,’ the philistine says.

And they open the doors to the chapel.

They glide open slowly, creaking.

A dull light through glassless openings.

And they both let out an endless scream when they see what’s lying there naked, almost draped across the raised slabs marking the site of the Fagelsjo family vault.

50

Death has no smell here. The stench of decay that meets Malin doesn’t come from the corpse, but from the forest surrounding the chapel.

The ground is waterlogged, but doesn’t seem able to flood.

Fredrik Fagelsjo’s body is naked.

Malin knows it is, even though it’s already lying on a trolley in a black bag designed for the purpose: transporting and concealing corpses.

She’s standing at the entrance to the Skogsa chapel, trying to escape the rain that the wind is driving towards her, looking at the gilded pictures of Christ on the walls, the haloes around the head of the Son of God, a halo that no one yet living seems to possess this autumn.

The vultures are being kept at a distance. She could see the expectation in their eyes as she walked past them. Their little Blackberries ready for notes, the starved cameras, their instincts aroused, finally something has happened again. Daniel isn’t there. Perhaps he’s on his way.

Sven Sjoman and Zeke beside her, silent and focused, thoughtful.

Fredrik Fagelsjo.

Murdered. Like a sacrifice on the family vault.

An autumn sacrifice.

But for what? And by whom?

The three detectives want to take the connection to Jerry Petersson’s murder for granted, but know that they can’t. No stab wounds this time, but a clear message nonetheless: a naked body on a grave.

They have to keep all their options open in the investigation, there’s no guarantee that the two murders are linked just because they almost share a crime scene, or because the victims have a shared history. Who knows what meandering pathways violence takes? Malin thinks. Dead ends, dark and lonely. The methods are clearly different, but it’s a myth that a murderer always kills in the same way.

The solicitor and the art expert.

They were in quite a state when Malin, Sven and Zeke arrived an hour or so ago, but they had had the sense not to go too far inside the chapel, before pulling back cautiously from the immediate vicinity.

The reason why they were there was obvious. And they hadn’t seen or heard anything.

No reason to detain them.

Karin Johannison and her two male colleagues from the National Forensics Lab are searching the scene, looking for fingerprints, picking up things invisible to the naked eye and putting them in plastic bags.

Karin, on the subject of Fredrik Fagelsjo once his body had been put inside its black plastic bag: ‘He appears to have died from a blow to the head. The wound looks like it could have been inflicted by a hammer. It struck him cleanly, so it isn’t possible to say if the perpetrator is right– or left-handed. No other obvious signs on the body, no violence against the genitals as far as I could see from a quick look.’

‘Was he murdered here or moved here?’ Malin asked.

‘In all likelihood he was moved here. There are definite signs of blood by the entrance. Even if his clothes are missing, I think he was undressed here. The fibres we’ve just found on the floor look like the ones I found on the body when I first checked it.’

‘So murdered somewhere else, but undressed here?’

‘Probably, yes.’

‘What about why he was brought here to the chapel, to this grave?’

‘Memorial stone.’

‘Same thing. What do you think about that?’

‘That’s not my area, Malin. I don’t think anything.’

‘And the way he was killed?’

‘It must have been a very hard blow.’

‘In anger?’

‘Maybe. But the murderer didn’t lose control, because then you’d expect more than one blow.’

And now Karin Johannison makes a sign to her colleagues.

The two men carry Fredrik Fagelsjo’s body out of the chapel.

What are you trying to say? Malin thinks as they pass her.

What do you want to tell us?

The family vault in front of her.

Fredrik Fagelsjo gambling away the fortune, the family estate. Is this your father Axel and your sister Katarina getting revenge? But why would they do it now, when the family has just inherited a lot of money and in all likelihood will be able to buy back the estate from Jerry Petersson’s father? Or was it the family that got rid of Petersson and now had to get rid of Fredrik because for some reason he can’t keep quiet or knows too much?

Or is this something else entirely? Does Fredrik have any connection to Goldman? It feels like a hell of a long shot. Or did Fredrik play a bigger part in the tragedy of that New Year’s Eve, did he do more than just arrange the party? Or has Fredrik been murdered because he murdered Jerry Petersson?

Why is all this happening now? If Jochen Goldman is somehow behind it all, it may simply be because he hadn’t got around to it before now. Who knows how much someone like that might have to tidy up from his past? Maybe he’s sent a lot of people to the bottom? Sent a lot of photographs?

Unless these murders aren’t connected at all? What enemies did Fredrik have? The tenant farmers?

Jerry, Fredrik. Did anyone have a reason to hate both of you?

The icons on the walls seem to glow, as if encouraging her to carry on.

In spite of the cold and rain, in spite of all the crap, Malin feels her brain starting to work again, trying to make sense of the possibilities presented by a double murder.

Her detective’s soul kicks in again.

There are no doubts, no grief any more. Just focusing on a mystery that needs to be solved.

‘Shall we go inside the house and run through what we’ve got?’

Sven’s voice doesn’t sound tired, but expectant, as if his police officer’s soul has come to life.

‘Good idea,’ Zeke says, turning away from the scene of violent death.

Malin, Zeke and Sven are standing in the castle kitchen going through the options, everything that Malin thought out in the chapel, and a few more possibilities besides.

‘Different methods,’ Sven says. ‘But I still think we’re dealing with the same murderer.’

Malin nods.

‘There are too many connections between the murders. The location, the victims’ histories. I’d be astonished if it weren’t the same perpetrator.’

‘Maybe the first murder was committed out of rage, and the second planned?’ Zeke ponders.

‘Unless Fredrik committed the first murder and was himself murdered in revenge,’ Sven says. ‘We simply don’t know. But the chances are that we’re dealing with one and the same murderer.’

‘And we can write off the parents of the kids in the car crash,’ Malin says. ‘They had no reason to want Fredrik dead. If they wanted to kill him for organising the party, they’d have done so long ago.’

They mention Jochen Goldman, agree that the connection is a long shot, but that they can’t dismiss the possibility entirely.

The three detectives are silent for a while, considering all the possible scenarios, sensing how elusive and multifaceted the truth is.

‘You two go and tell Axel Fagelsjo,’ Sven goes on. ‘Johan and Waldemar can inform Katarina.’

‘And question them. We’ll handle the old man,’ Zeke says. ‘After all, they could well have had something to do with this.’

‘True enough,’ Sven says. ‘They might have wanted Fredrik out of the way because of his business dealings, or they could be guilty of Petersson’s death and he was on the point of cracking and talking.’

Malin shakes her head sceptically, but says nothing.

‘And we’ll have to take a closer look at Fredrik’s life. His dealings with the bank,’ Sven says. ‘Maybe he didn’t only lose his own family’s money? He could have enemies. More work for Johan, Waldemar and Lovisa in Hades.’

‘What a bloody mess,’ Zeke says. ‘How the hell are we going to get anywhere with all this?’

‘They can check all the business stuff in Hades. A bad deal seldom occurs in isolation,’ Sven says, then he gives Malin a sympathetic look that annoys her and makes her want to say: ‘Stop worrying so fucking much. I’ll be fine,’ then she thinks: What if I’m not, what if I can’t hold on? What happens then? And then the indistinct concept of rehab pops into her head like a small firework.

‘And we’ll have to talk to Fredrik’s wife,’ Zeke says. ‘She hasn’t reported him missing.’

‘You do that,’ Sven says. ‘He might have told her he was going somewhere. Any other thoughts?’ Sven goes on. ‘The car crash?’

‘Dubious. But we have to ask ourselves why he was laid on the family vault naked,’ Malin says. ‘Almost like a sacrifice.’

‘Do you think the murderer’s trying to tell us something?’

‘I really don’t know. Maybe he or she is trying to make us believe that there’s something to tell. Get us to look in a particular direction. Possibly towards the Fagelsjo family themselves. It’s all been in the papers, after all.’

‘You mean it could be someone in the family who wants to be discovered?’

Zeke, questioning, beside her.

‘More the opposite,’ Malin says.

‘How do you mean?’

‘I don’t know,’ Malin says. ‘It just feels like there’s something here that doesn’t make sense.’

‘You’re right about something not making sense. Well, we’ll have Karin’s report tomorrow, and we’ll take it from there,’ Sven says. ‘And we need to map out Fredrik’s last twenty-four hours. We haven’t exactly got very far with Petersson. Unless there really isn’t anything to fill in that we don’t already know about, apart from his encounter with the murderer.’

‘So how do we think Fredrik got here?’ Zeke asks.

‘Forensics are going to have a look for tyre tracks around the castle. See if they can find any that don’t match the solicitor’s car. There’s nothing to suggest that anyone’s been inside the castle. The alarm was on when they arrived. Well, go and see Axel Fagelsjo now. Before the media announce it.’

‘It’s already out,’ Zeke says.

Cars from the Correspondent and local radio. The main national broadcaster, SVT. TV4. Local television news.

Over-eager vultures. Even if they don’t mention any names, the victim’s relatives can always put two and two together, and no one should find out about a death through the media.

Still no Daniel out there.

In his place an older reporter that Malin, oddly enough, doesn’t recognise, and the photographer, the young girl with dreadlocks that Malin knows takes good pictures. What is it she’s trying to capture here?

Death?

Violence? Evil. Or fear.

Whatever you do, don’t take any pictures of me. I look like a pig.

Sven’s mobile rings.

He hmms a few times beside them. Hangs up.

‘That was Groth in Forensics,’ he says, turning towards Malin. ‘The examination of the pictures of your parents didn’t come up with anything, I’m afraid.’

Malin nods.

‘Shit,’ Zeke says quietly. He was furious when he found out about the pictures this morning. ‘Couldn’t the pictures have something to do with all this?’

‘Somehow it all fits together, doesn’t it?’ Malin says. ‘It’s just a question of how.’

Malin leaves the kitchen and goes out into the main hall, stopping once more in front of the huge painting of a man rubbing suncream onto a woman’s back.

Thinks that the picture is beautiful and tawdry at the same time.

She feels something as she looks at it, but she can’t put her finger on what.

Sven walks past her.

She says: ‘I’d like Zeke and I to deal with Katarina Fagelsjo.’

‘OK, if you think that’s a better idea,’ Sven says. ‘Waldemar and Johan can talk to Fredrik Fagelsjo’s wife instead. But start with his father. And not a word to the bloody media.’

51

Axel Fagelsjo is standing quietly in front of the sitting-room window. The fog that drifted in when the rain stopped is obstructing the view of the Horticultural Society Park, the naked trees are like thin silhouettes of bodies, and Axel seems to be looking for something, as if he has a feeling that someone down in the park is watching him from a distance and was just waiting for the right opportunity to attack him.

It was as if he knew why they were there, as if he knew what had happened, and, while they still were in the hallway, he said, ‘Out with it, then!’ to Malin and Zeke, as if he had spent all night waiting for them. They asked him to go through to the sitting room and take a seat, but the old man refused: ‘Just say what you’ve got to say here,’ and Malin sat on a worn old rococo stool by the door and said straight out: ‘Your son. Fredrik. He was found dead in the chapel at Skogsa this morning.’

The terrible meaning of the words blew away her insecurities.

‘Had he killed himself? Hanged himself?’

And in Axel Fagelsjo’s face, in the pink confusion of wrinkled skin stretched over fat, Malin saw a hardness, but also something like clarity.

I despised my son. I loved him.

He’s dead, and perhaps now his sins can be forgiven. His sins against me. Against the memory of his mother. His ancestors.

And, deep in his shiny pupils, grief, yet still somehow hidden behind layer upon layer of self-control.

‘He was murdered,’ Zeke said. ‘Your son was murdered.’

As if he wanted to provoke a reaction in Axel, but he merely turned away, went into the sitting room, and over to the window where he is now standing, his back to them as he answers their questions, apparently unconcerned by the circumstances. Malin wishes she could see his face now, his eyes, but she is sure there are no tears running down Axel Fagelsjo’s cheeks.

‘We can tell you the details of your son’s death if you want to hear them,’ Malin says. ‘We know a fair amount already.’

‘How he was found, you mean?’

‘For instance.’

‘I’ll be able to read about it in the paper soon enough, won’t I?’

Malin still tells him what they know, without going into any great detail. Axel remains motionless by the window.

‘Did Fredrik have any enemies?’

‘No. But of course you know that I wasn’t happy with him after the financial debacle.’

‘Anyone who might be trying to get at you?’

Axel shakes his head.

‘What were you doing yesterday evening and last night?’ Zeke asks.

‘I was at Katarina’s. We were talking about the possibility of buying back Skogsa from the estate. Just her and me. It was late when I walked home.’

Father and daughter, Malin thinks. They’re together on the night when Fredrik, the brother, the son, is murdered. Why?

‘Nothing else you think we should know about Fredrik? Any other business deals that might have gone wrong?’

‘He didn’t have that level of authority at the bank.’

‘No?’

‘He was a middleman.’

‘Could he have had anything to do with Jochen Goldman?’

‘Jochen Goldman? Who’s that?’

‘The embezzler,’ Zeke says.

‘I don’t know of any Goldman. But I can’t imagine Fredrik had anything to do with an embezzler.’

‘Why not?’

‘He was too cowardly for that.’

Malin and Zeke look at each other.

‘What about Fredrik’s wife? What was their relationship like?’

‘You’ll have to ask his wife about that.’

‘Do you want us to arrange for someone to come and be with you? We’d prefer not to leave you alone.’

Axel snorts at Malin’s words.

‘Who would you send? A priest? If you don’t have any more questions you can go. It’s time to leave an old man in peace. I need to call an undertaker.’

Malin loses patience with the old man.

‘I don’t suppose your family had Jerry Petersson killed, and then Fredrik was on the point of cracking up and confessing? So you murdered him?’

Axel laughs at her.

‘You’re mad,’ he says.

And Malin realises how much it sounds like a conspiracy theory.

‘We’re going to see Katarina now,’ Malin goes on. ‘Perhaps you’d like to call her first?’

‘You can tell her the news,’ Axel Fagelsjo says. ‘She stopped listening to me long ago.’

Malin and Zeke take the stairs back down, their steps echoing in the stairwell. Halfway down they pass a black cleaner washing the steps with a damp mop.

‘He’s a cold bastard, that one,’ Zeke says as they approach the door.

‘He can shut off completely,’ Malin says. ‘Or rather, shut himself in.’

‘He didn’t even seem upset. Or the least bit curious about who might have killed his son.’

‘And he seemed even less concerned about Fredrik’s wife,’ Malin says.

‘And his grandchildren. He didn’t mention them at all,’ Zeke adds.

‘Presumably he’s too old for rage,’ Malin says.

‘Him? He’ll never be too old for that. No one gets that old.’

Axel has sat down in the armchair in front of the open fire.

He clenches his big, spade-like hands, feels his eyes well up and the tears run down his cheeks.

Fredrik.

Murdered.

How could that happen?

The police.

No one to talk to, the fewer words spoken, the better.

He sees his grandchildren running through the living room out at the Villa Italia, chased by Fredrik, then they run on through the pictures inside him, children’s feet running across the stone floors of the rooms of Skogsa. Who are the children? Fredrik, Katarina? Victoria? Leopold?

I want my grandchildren here with me, but how can I approach her, Bettina? His wife, Christina, she’s never liked me, nor I her.

And really, what would they want me for?

The truth, Axel Fagelsjo thinks, is for people who don’t know any better. Action is for me.

You’re a widow now.

Your two children fatherless.

Johan Jakobsson looks at the woman sitting in front of him on the sofa in the large living room of the Villa Italia, hunched up and tear-streaked, yet still radiating a sort of faith in the future. She must be financially secure, and Johan has seen this before in women with children when he arrives to break news of their husband’s death, the way they immediately seem to focus all their energy forward, onto the children, and the work of limiting the damage to them.

Johan leans back on the sofa.

Christina Fagelsjo looks past him, towards Waldemar Ekenberg, who is sitting on a stool by the grand piano, rubbing the bruise on his cheek.

Christina has just explained that she decided to spend the night at her parents with the children after drinking wine at dinner. That she often ate dinner with the children at her parents without Fredrik, ‘they’ve never got on very well, Frederik and my parents’, and that her parents can confirm that she was there.

‘You didn’t call home?’ Waldemar asks.

‘No.’

‘And he wasn’t here when you got home?’ Johan asks, and he is struck by the idea that Christina could have murdered her husband to get a share of the recent inheritance before it was spent trying to buy back Skogsa.

A long shot, he thinks. The woman in front of him is no murderer. And the inheritance must have gone mainly to Axel. But she does appear to be right-handed. Along with practically everyone else.

‘I assumed he must be at the bank.’

‘Did he have any enemies?’ Waldemar asks, and it strikes Johan that it’s just the right moment for that question, phrased in that way, and reluctantly he has to admit that he and Waldemar work well together as police officers. He is convinced that Christina is telling the truth when she replies.

‘Not that I know of.’

‘His father? His sister?’

‘You mean because of the debacle?’

Christina shrugs her shoulders.

Waldemar Ekenberg strikes one of the keys of the piano gently. Light in Christina Fagelsjo’s eyes.

‘I know we’ve asked before,’ Johan says. ‘But do you know why he tried to escape from us? Could it have. .’

‘We talked about it the day he was released. He got scared, panicked. Anyone might have done in those circumstances.’

‘Do you think it occurred to him that driving under the influence of alcohol is illegal as well as dangerous?’

‘Sometimes he thought he was above that sort of thing. Sometimes rules were meant for other people.’

‘What was your marriage like?’ Johan goes on, and Christina answers without thinking.

‘It was a good marriage. Fredrik was a generous man. The Fagelsjo family are good at love.’

And at the moment Christina says the word love, two small children run into the room, a little girl and an even younger boy. The children rush over to their mother, talking at the same time: ‘Mummy, Mummy, what’s happened? Mummy, tell us.’

‘Mum? Is that you? It’s a bad line.’

Tove.

It’s not yet half past two and it’s already starting to get dark over on the horizon beyond the jagged, shredded Ostgota plain. Malin is sitting in the Volvo with Zeke, on their way to Katarina Fagelsjo’s address.

She wants Tove to say she’s coming round this evening, that she’ll stay the night in the flat in the city and not out at Janne’s.

They drive past Ikea, the car park full at this time of day, and at the petrol station near Skaggetorp, people are filling their shiny, well-kept cars. She looks at the spot where she parked when she went to buy clothes and seems to see two men gesturing to each other beside a car.

Malin blinks.

When she opens her eyes again the men are gone.

Down by the river and the Cloetta Center, the new high-rise block is going up, the tower, a miniature skyscraper, a pointless piece of showy architecture so that another of the city’s vain property developers can stamp his name on Linkoping’s history.

‘Mum? Is that you? I can’t really hear you.’

‘I’m here,’ Malin says. ‘Are you coming home this evening? We can do egg sandwiches.’

‘Maybe tomorrow?’

And mother and daughter talk, about how they are, what they’ve been doing, what they’re going to do.

Malin hears her own voice, but it’s as if it doesn’t really exist. As if Tove’s voice doesn’t exist. And this absence of voices forms a loneliness, which forms itself into an inadequacy, which forms itself into grief.

The car pulls up outside Katarina Fagelsjo’s modernist villa down by the river, fallen apples are still lying under the trees, and only now does Malin see the decay, that the house needs plastering and that the entire garden could do with being cleared out and maybe replanted.

Malin and Tove hang up.

The windscreen wipers are working frantically.

Their movement makes the shape of a heart, Malin thinks. Painted hearts, rubbing suncream onto a woman’s skin.

Signs of love that were never interpreted.

And she knows which question to ask Katarina Fagelsjo.