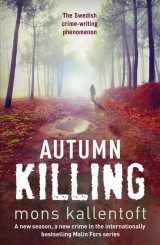

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

8

There’s something that’s no longer moving.

Something that’s stopped for ever. Instead whatever it is that’s surrounding me is moving. I don’t have to breathe to live here, just like it was long ago, where everything began and I floated and tumbled inside you, Mum, and everything was warm and dark and happy apart from the loud noises and rough jolts that shook my senses, the little senses I had then.

No warmth here.

But no cold either.

I can hear the dog. Howie. It must be you, I recognise your bark, even if it sounds like you’re so far away.

You sound anxious, almost scared, but what would a dog like you know about fear?

Mum, you taught me all about the fear to be found in pain. Am I closer to you now? It feels like it.

The water ought to be so cold, as cold as the heavy hail that’s been firing from the skies all autumn.

I try to turn around, so my face is looking up, but my body no longer exists, and I try to remember what brought me here, but all I can remember is you, Mum, how I rocked in time with you, just like in the water of this moat.

How long am I going to be here?

There’s a ruthlessness here, and I see myself reflected in that ruthlessness, it’s my face, my sharp, clean features, the nostrils whose flaring can scare people so, no matter who they are.

Pride.

Am I proud?

Is that time past now?

Now that everything’s still.

I can float here for a thousand years, in this cold water, and be master of this land, and that’s just fine.

The deer need to be culled.

The hares need to be eradicated.

People need to leave their warm, secure water.

New days need to be born.

And I shall be part of them all.

Own them all.

I shall lie here and see myself, the boy that I was.

And I shall do so even if I’m scared. I can admit it now; I’m afraid of that boy’s eyes, the way the light opens the world up to him, in jerks, like the desperate bark of an abandoned dog.

9

Linkoping and district, summer 1969

The world comes into being through the eyes, because if you close them there are no images, and the boy is four years old when he learns to recognise his own eyes, pebble-sized deep-sea-blue objects set at perfect distance from each other in an equally perfectly shaped skull. Jerry realises what he can do with those eyes, he can make them flash so that remarkable miracles happen, and, best of all, he can get the nursery-school teachers to give him what he wants.

His reality is still directly experienced. What does he know about the fact that on this very day, tons of agent orange and napalm are being dropped onto tropical forests where people hide in holes deep underground, waiting for the burning jelly to dig through the ground and destroy them?

For him, warm is simply warm, cold is cold, and the black-painted copper pipe attached to an endless, rough, red, wooden surface is so hot that it burns his fingers, albeit not in a dangerous way, but in a way that’s nice and makes him feel both safe and scared; scared because the warmth in him awakens a feeling that everything can end.

A lot happens in this life.

Cars drive. Trains travel. Boats on the Stangan River blow their whistles.

He lies on the grass in the garden of his grandmother’s cottage, feeling the dense smell of chlorophyll possess him, seeing how the grass colours his knees and body green. In the evenings, when the midges attack, Daddy puts a bright yellow plastic bathtub on the grass and the water is warm on his skin and the air around him is cold, and then he runs alongside the howling grass-scented monster that gives off a sharp smell and Daddy sweats as he pushes it across the grass. The blades sniff out the boy’s feet, spraying grass cuttings from its broad maw; this isn’t a game and Daddy sees the look in his eyes but doesn’t let that put him off. Daddy turns the monster, chasing the boy through the garden, crying: ‘Now I’m going to cut your feet off, now I’m going to cut your feet off’, and the boy runs down to the edge of the forest, feels like running until the lawnmower can no longer be heard.

But inside, in the kitchen with Mummy and Grandma, his eyes work and he realises it’s best to eat buns when they’re fresh, before the mould creeping up from the floor has a chance to make them taste spoiled.

Daddy comes home to the cottage after work.

With bags that clink. And then Mummy wants to sit still. She feels better after Daddy comes with the bags, Grandma too, and they are happy, but not properly happy.

The sun disappears and the heat in the black-painted copper is exchanged for a metallic smell in the chilly stairwell and multicoloured glass marbles rolling in the sand of a sandpit, and then down into a hole, and someone’s in the way, another boy.

Go away. You’re not supposed to be there. And Jerry’s hand flies up, strikes where he means it to, across the nose, and then the blood comes and the boy screams, the boy he’s hit screams out loud and he himself screams: ‘Plaster!’, not: ‘He hit me first.’ He regards himself as too good for a lie like that.

In the world of direct experience there is a dead cat in a rubbish bin by the swings in the park. He once gave that cat some cream.

There are feelings floating in the two rooms of the flat, there are questions directed at him. ‘Do you know that we live in Berga?’ ‘That Daddy works for Saab, putting together planes that can fly through the air faster than words?’ And he recognises the laughter, it lacks warmth, and they sit on the orange and brown patterned sofa, the one they make into his bed each night, and they pour out drinks from the bottles they always have in a bag. Then they talk louder, the air turns sweet and unpleasant, and they look at black-and-white people on a screen, and Mummy can get up in a way that she can’t otherwise, she can fly up from the sofa and they dance, she only does that when they’ve been drinking and he likes watching Mummy dance. But then Daddy starts chasing him, he’s the lawnmower trying to catch him and hit him on his arms and legs, and the boy is four years old, and creeps out of an unlocked front door, into the world outside that is full of life waiting to be conquered; a cat to be buried, a swing to be swung up to the sky, car and trains to be driven, people shouldn’t lie in vomit and pain, shouldn’t chase him anywhere.

So he screams.

He breaks things.

He draws on the walls with crayons.

He gets hold of matches and sets fire to the world, watches his wooden boat burn in the sand, and feelings that he doesn’t know the name of, feelings that might not even have any names, drift through the flames, and the smouldering hull rests on a desolate patch of sand enclosed by a wooden frame.

Daddy’s despair. How the boy’s little body flies into the radiator beneath the living-room window when drunk Daddy stumbles over him. Mummy’s tired blinking eyes.

Pain, which as yet is always new.

Nothing is fixed.

Nothing has set into its final form.

Perhaps that is why nothing is possible.

The boy lies in his bed at night. He is awake. In the August evening there is a hint of the first chill of autumn.

He already knows there is another world, but he doesn’t think about it, he is busy living in the world of directly experienced reality.

There is no reflection as he daydreams in the darkness about killing his father. Killing him with rays that shoot from his blue pebble-eyes. He will make the lawnmower shut up.

Its blades will no longer snap at his heels.

10

The eye, as black as the water, seems to wink at Malin Fors as the head bobs in the gentle, scarcely perceptible waves.

The yellow raincoat is almost luminous in the water.

The throbbing in her own skull.

The dog barking over in the car by the edge of the forest. The sound like distant cannon-fire, as if it were inside a pressure cooker.

The dog was standing by the edge of the moat when they arrived. Barking like crazy, but it didn’t object when it was led to the car, just carried on barking.

Bang, bang.

What can that eye in the water see now? What was the last thing that eye saw?

The bobbing motion of the head, the little snake-like fish around it, the throbbing in Malin’s own head: two things that will give this day its very own insane structure and logic.

Skogsa Castle. She’s driven past the end of the drive many times, but she’s never seen the castle before, never had any reason to drive into the forest and out across the fields. But she’s seen pictures of it in a book about Swedish castles and manor houses in her parents’ apartment by the old Infection Park. A fuck-off great stone box, jam-packed with snobbery, even if there’s something restrained about the building itself. The lines are straight, practically no ornamentation; humility in the face of the dramas that have unfolded here over the years.

Malin is crouching at the side of the moat. Large, smooth rocks that must have come straight from the quarry slope steeply down into the water, the green light from the lanterns reflected in its surface. The fish down there, hundreds of them, not much bigger than sprats, blacker than the water as they move around the body.

Malin has pulled the zip of her GORE-TEX jacket right up, the hood tight around her head, three layers underneath and still she’s freezing, feeling the heavy raindrops hammering the fabric. Zeke had the coat in the car, making a comment about her ancient sweater when he picked her up, asked if she’d bought it at the Salvation Army. When he saw her jeans he grinned: ‘Eastern European fashion’s the next big thing, is it?’

But he didn’t remark upon the fact that he was picking her up from the flat, even if he must have wondered what she was doing there.

The cold helps her head to clear.

Helps her gaze focus, so she can concentrate on the corpse floating on the surface, on the blond hair, on the eye staring up at them.

Zeke by her side.

Wide awake. Curious.

‘How the hell are we going to get him out?’

‘We’ll have to get divers from the fire brigade.’

The report of the body had reached the police station at a quarter past eight. Malin had heard the phone ringing when she got out of the shower and it had had an unmistakable note of urgency, as if the phone had its own consciousness and could change the way it sounded according to the circumstances.

Zeke’s voice: ‘Some farmers have called in to say that they’ve found a man murdered out at Skogsa Castle.’

She had thrown on her clothes and they had set off south towards Skogsa. He had commented on her breath and told her she looked terrible, wondered if she’d been drinking, but she just said she’d had a couple of glasses of tequila yesterday evening, joking that he must have a very sensitive nose.

They had been the first unit on the scene, and as they arrived and parked at the edge of the forest, the large castle doors had opened and out came the two men that she now knows are the tenant farmers, Ingmar Johansson and Gote Lindman.

They had waited where they had been told while she and Zeke looked at the scene and led the dog away, carefully, without contaminating the crime scene. The pair had explained that they were supposed to be hunting deer with Jerry Petersson, but that he hadn’t met them at the agreed time, and that they had found him, or at least what they assumed to be his body, down in the moat.

‘I mean, you can’t really see for sure,’ Johansson had said.

‘But it’s him,’ Lindman had added. ‘He had a coat just like that.’

The corpse in the water.

Jerry Petersson.

Hotshot lawyer. Businessman. The slightly dodgy commercial lawyer who had made a fortune in Stockholm and moved back home when he got the chance to buy Skogsa Castle. Malin had read the profile in the Correspondent.

If it really is him.

The throbbing in her head. The dog’s barking. Two patrol cars had just arrived at the edge of the forest. No holding back with a suspected murder.

Jerry Petersson.

But who else could it be? Malin closes her eyes, feeling her headache, listening to the air, and she imagines she can hear the rain falling on an invisible body, someone whispering words she can’t understand, words that want to make the world comprehensible, easy to understand and absorb, but they vanish before she has time to work out what they mean.

The divers arrived thirty minutes later, and now their red emergency vehicle is parked alongside Zeke’s car, forensics expert Karin Johannison’s blue Mercedes, and Sven Sjoman’s red Volvo. The cars are parked in a clearing on the other side of the moat, a long way from Petersson’s Range Rover and the tenant farmers’ Saab. The journalists have started to appear, and they are standing in a huddle with cameras of all sizes, flashing as though they were some huge lightning-filled stormcloud. They’re shouting at the police, but are ignored.

They can smell something tasty, the reporters. Front pages. A paper-selling story that will appeal to people’s desire to read about death and violence from a safe distance.

Just like some shoddy thriller, Malin thinks. Life imitating art.

None of the police or fire brigade have driven up in front of the castle.

No one wants to spoil any tyre tracks, footprints or signs of a struggle on the gravel, or whatever else Karin Johannison can find. Malin can see Karin moving around the Range Rover, taking pictures, shaking her head, wiping the rain from her forehead. Even in a yellow raincoat, that woman still manages to look glamorous.

She nodded to Zeke when she arrived, and he pulled his dark-blue raincoat tighter round him.

The nod back took far too long, Malin thinks, knowing that it hides something she’d rather not know about, a truth made visible in the way that only a real hangover can give a new slant on things.

With listlessness comes clarity.

But what do I know about what they get up to? Maybe I’m just imagining it.

None of the firemen, the divers is anyone she recognises.

Thank God. But they must know who she is, they must know all about her and their colleague Janne.

Don’t think about yesterday.

Just thank God for this case. Think about the victim in the moat instead, whoever he is, however he got there. Malin watches as the divers, in their black frogmen’s outfits and yellow visors, lower themselves down from the bridge over the moat on thick ropes, their bodies slowly penetrating the surface of the black water.

Karin beside her and Zeke now.

The rain is horizontal, hitting them straight in the eyes, and over at the edge of the forest, two hundred metres away, on the far side of a meadow, there are low banks of fog.

‘Careful!’ Karin shouts as the divers approach the body. ‘As gently as you can.’ And they fasten a sling around the corpse, give the thumbs-up to a third fireman who is standing on the bridge with a winch, and then there is a whirring sound and the body in the water starts to rise, held carefully by the divers treading water.

‘What a shit morning,’ Zeke says.

Sven Sjoman, wearing a green raincoat, has joined them.

‘So, what do we think?’

‘Well, he didn’t jump in of his own volition,’ Malin says. ‘Or fall in. Grown men don’t often fall into water, unless they’re seriously drunk or have a heart attack or something like that.’

‘If it is Petersson, he’s somewhere around forty-five. Not many heart attacks at that age.’

‘No. He probably had some help.’

‘That seems most likely. We’ll know for sure when Karin’s got the body up.’

Malin nods.

‘If it is Petersson, and if he has been murdered, it’s every journalist’s wet dream.’

‘Careful!’ Karin calls as the rotating body is lifted clear of the water and is left hanging, feet down, the water dripping from its yellow raincoat, brown trousers and a pair of black leather boots.

The dripping water is coloured red. The yellow raincoat has been perforated by masses of holes and Malin can see a number of deep injuries to the body, and a mixture of blood and water is streaming from what must be dozens of stab wounds. The blood mixes with the rain. It’s raining blood, Malin thinks. So you didn’t exactly fall into the moat drunk, did you?

Little silver fish are falling from the victim’s mouth, wriggling like abandoned babies on their way down to the safety of the water.

Snake fish, Malin thinks.

A black eye staring right out into the rain and the thin fog that has drifted down into the moat. The corpse’s other eye is closed.

You look surprised, Malin thinks. But are you really?

Am I surprised?

Hardly.

The water is no longer embracing me.

I am leaving your memory, Mum, and instead I’m hanging here staring down at the water, and off towards the castle, at these strangers.

I can hear and see Howie, he’s barking even more fiercely now. Can he see the holes in my body? I know there are a lot of them, but I can’t feel any pain, just the wind blowing through me.

Who are they, these people?

What do they want with me?

Are they the Russian soldiers from the old stories?

I’m moving slowly upwards, towards a whirring noise, and I’m spinning around and around, but it’s not making me dizzy, and now I’m heading towards the bridge, held by a pair of firm arms, and gradually I sink lower, my stiffening, bloody body.

A slapping sound as I touch the ground again.

I am lying on my back.

Black plastic under me. How can I know that I’m lying on my back when I can’t see or feel anything?

But I suppose that’s what it’s like now.

All those people standing by the edge of the moat looking at me. Who are they?

I’ve got my suspicions, but I don’t want to believe it’s true, that this has finally happened. I refuse to accept it. But there’s probably no point trying to resist. And if it has happened, there are plenty of riddles to solve.

And the buzz of the lawnmower isn’t here.

A woman’s face in my field of vision. She’s beautiful.

Then another woman.

She could have been beautiful, but right now it looks like she could do with six months’ sleep, her eyes seem completely devoid of any joie de vivre.

And the way they’re talking, I don’t actually want to hear what they’re saying, not yet.

‘It’s Petersson,’ Karin says as she and Malin crouch over the body lying on the bridge spanning the moat. ‘I recognise him from pictures in the Correspondent and Kalle’s business magazines.’

‘We can ask one of the tenant farmers to identify him,’ Malin says. ‘But I recognise him too, so there’s hardly any point.’

Johansson and Lindman are waiting inside a patrol car. They’re planning to interview them properly once they’re done out here.

‘Apart from the wounds, he’s got a large bruise on the back of his neck,’ Karin says. ‘In all likelihood, the injuries to his torso are knife wounds. Everything suggests the sort of extreme violence that you almost only see when someone loses control. You can take it for granted that he didn’t inflict these wounds on himself. But I can’t say much more than that out here, we need to get him back to the city to see if I can get anything else from the body. It’s impossible to examine the ground out here. The rain has swept away any evidence. I might be able to find some traces of blood in the gravel, but it’s far from certain.’

The ambulance arrived a short while ago.

Driven by Stenlund, one of Janne’s former colleagues. He waved a cheery hello and asked how Janne was, and Malin replied that he was fine.

She looks at the corpse.

The open, almost magically blue eye looks as if it’s trying to escape its socket, and she feels sick, wants to get up, but looks up at Zeke instead.

‘What do you think?’

‘Someone stabbed him in a fit of rage, whacked him on the neck and dumped him in the water. Or the other way round.’

‘OK, from now on this is officially a murder investigation,’ Sven says.

Rage, Malin thinks. My hand raised against Janne, bloody hell, I was so angry, imagine if I’d had a knife in my hand, but don’t think, don’t think, say instead: ‘We need to examine the car and the surrounding area, the whole castle and the other buildings, just to see if we can find anything. Anything that suggests a struggle, or any other evidence, come to that. Anything that looks like the murder weapon. Chances are we’re looking for a knife, and a rock or something similar.’

‘OK,’ Sven says. ‘We have to marshal our forces, have an initial meeting before we get going. And we need to interview the two men who found him. Call in the rest of the team. Karin, can you give the OK for us to use one of the rooms inside the castle?’

Karin nods.

A car appears at the edge of the forest.

Another of the Correspondent’s blue and white staff cars.

Everything in due course, Malin thinks, feeling her stomach contract and wanting to throw up.

Malin walks over the gravel towards the doors of the castle, thinking about the hundreds of people who must have walked that path over the years. In fear or pride, tired, or with the elation that only owning considerable property can bring.

These people are like spirits anchored to the landscape, ghosts that don’t want to leave the ground and fly.

She had just closed Jerry Petersson’s open eye.

Wanted him to find peace, to stop having to stare at the world with a cold, dead gaze. It’s quite enough for those of us who are alive to have to see the world like that, she thought. Then she looked at him. His blank face, the exposed wounds on his reasonably toned body. Who were you? she wondered. What sort of person do you have to be to end up where you did? How did all this come to be yours? Who got so angry with you that he or she stabbed you over and over again?

Then she walked around the castle, finding a small chapel at the rear, but the door was locked. She peered in, and in the middle of the octagonal space was a raised dais that she assumed must mark the Fagelsjo family vault. Dozens of icons stared down from the walls at her, the gold surrounding the figures of Christ defying the darkness of the season, saying: ‘Beauty is possible’.

On the other side of the castle stood two big red Stiga tractors, equipped for cutting grass, silent, as if they’d been used for the last time, their blades removed.

Malin climbs the steps up to the castle, breathing in the morning air.

In spite of the nausea, she feels excited.

And that makes her ashamed. Thinks: you can feel ashamed of any emotion. Was it shame that killed you, Jerry? What were you ashamed of? If you were ashamed of anything at all. Maybe you have to be free from shame to own and live in a castle?

In the castle’s entrance hall a huge chandelier hangs oddly alone up above. As if it’s waiting to spread light, Malin thinks. And that painting on the wall. A man, a woman. A bit of suncream on her back. Love? Suppressed violence. Definitely.

That picture probably cost a fortune, Malin thinks.

Muttering.

Questions.

Don’t imagine I’m going to answer.

Surely you have to do something to justify your salary?

A camera clicking.

My eternity is made eternal.

I can’t move. Yet I could still see Malin Fors looking at my collection of icons just now.

Maybe I can have some fun with this. Play with justice, the way I have so many times in the past.

But how can I do that? My body’s full of holes. This doesn’t make sense. Doesn’t make sense.

Help.

Help me.

Malin Fors.

I don’t recognise this fear, it’s completely new.

Only you can get me out of here, Malin. That’s right, isn’t it?

Only you can silence this fear that I’ve been so desperately trying to evade. The fear that you’re trying to escape too. That’s right, isn’t it?