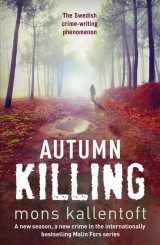

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

42

Zeke runs across the car park towards the entrance to the police station. The damp is running down the old ochre-coloured barracks, which has been given a new lease of life as the home of the city’s police, courts and the National Forensic Laboratory.

He swears to himself about this fucking bastard weather, but knows there’s no point in cursing the forces of nature, it’s utterly pointless and gets you nowhere.

In the rain his thoughts go to Martin.

In the NHL. The lad already has enough money to be able to relax in the sun until his dying day.

And the grandchild I’ve hardly seen.

What am I up to?

Andreas Ekstrom’s father, Hans.

Only fifteen minutes since I left.

An angry old man in an old, run-down house. All hell broke loose when Zeke said that Jerry Petersson had probably been driving the car when his son died.

Hans Ekstrom got up from the chair where he was sitting in the kitchen and shouted at Zeke that that was all crap, and he wasn’t about to let some bastard show up and stir that all up again now that he’d finally managed to put it behind him.

Hans Ekstrom had refused to answer any questions after that, but to judge from his reaction, what Zeke told him came as a complete shock.

Which meant he had no reason to murder Jerry Petersson. Unless Hans Ekstrom was a really good actor. A right-handed one at that.

Hans Ekstrom had concluded by cursing the Fagelsjo family: ‘They couldn’t even be bothered to send flowers to the funeral.’

They could have done that, Zeke thinks as he opens the door to the police station, evidently the new automatic doors aren’t working, the rain and damp have probably got into their mechanism and stopped them functioning.

Malin.

Zeke sees her sitting at her desk, and she looks so tired, utterly exhausted. If the sun had been shining down in Tenerife, it sure as hell hadn’t been shining on her.

A shadow of a person.

Is that what you’re turning into, Malin?

He feels like going over and putting his arm around his colleague, telling her to pull herself together, but knows she would only get angry.

She looks up and catches sight of him, doesn’t say anything, just looks back down at the papers on her desk again.

Zeke turns and goes upstairs to Sven Sjoman’s room.

He’ll just have time before their meeting.

Sven is standing by the window, looking out at the main building of the University Hospital and its eastern entrance. The white and yellow panels covering the ten-storey building are shaking in the wind, seeming to want to let go and fly across the city, coming down to land in a more bearable site.

Zeke takes a few steps inside the room.

‘Don’t say anything to Malin,’ he says. ‘She’d never forgive me for going behind her back, but you can see the way she is. She’s drinking way too much.’

Sven shakes his head.

‘This conversation stays between the two of us. I’m glad you’ve mentioned it, because I’ve been giving it a lot of, well, a lot of thought.’

Sven turns around.

‘She’s not holding everything together,’ Zeke says. ‘I can’t bear to see it. I’ve tried. .’

‘I’ll talk to her, Zeke. The trip to Tenerife was partly an attempt to give her a bit of breathing space.’

‘You should see her now. It doesn’t exactly look like she spent her time in a luxury spa.’

‘Maybe the trip was a stupid idea. We’ll have to see how it goes,’ Sven says. ‘You’re making sure you drive when you go out together?’

Zeke nods.

‘I drive pretty much all the time.’

He pauses.

‘I’m sure what happened in Finspang last year hit her hard,’ he goes on.

‘It did,’ Sven says. ‘But who wouldn’t be badly affected by something like that? I don’t think she can understand that. Or accept it.’

The clock on the wall of their usual meeting room says 15.37.

The investigating team is all there.

Windows here, unlike in paperwork Hell.

No children in the nursery playground, but Malin can see them through the windows, running about the rooms, playing as if this world was altogether good. A red and blue plastic slide. Yellow fabrics. Clear colours, no doubts. A comprehensible world for people who grab life with both hands and live in the present.

The people in here, Malin thinks, are the exact opposite.

Karim Akbar’s face is composed, his body seems to have been taken over by a new sort of middle-aged seriousness, on the verge of exhaustion.

Autumn is wearing us down, Malin thinks. We’re turning into characters in a black-and-white film.

Zeke, Sven Sjoman, Waldemar Ekenberg, Johan Jakobsson, even young Lovisa Segerberg from Stockholm, seem ready for a long break from anything involving police work and rain.

The investigation.

Right now it looks as if it’s in danger of rusting solid, like the entire city.

Lines of inquiry.

Snaking back and forth across our brains like the lights on a communal ski track.

Suspicions. Voices. All the people and events that emerge when they lift the stones that made up Jerry Petersson’s fairly short life.

Sven is standing at the whiteboard at one end of the room. On the board he has written a list of names in blue marker pen.

Jochen Goldman.

Axel, Fredrik and Katarina Fagelsjo.

Jonas Karlsson.

Andreas Ekstrom and Jasmin Sandsten’s parents.

Then a row of question marks. New names? New information? Anything that can help us move on?

Malin takes a deep breath. Looks across at the children in the nursery. Hears Sven’s voice, but can’t bring herself to say anything.

Fragments from a meeting.

Her own account of her trip to Tenerife.

That Jochen Goldman is ambiguity personified.

Her encounter with Andreas Ekstrom’s mother. The others listen attentively. Lovisa tells them that she is steadily working through the files and contents of Jerry Petersson’s hard-drives, but that it would take at least five specially trained police officers to do it at anything like an acceptable rate, and Karim saying: ‘We don’t have the resources for that.’ They still haven’t found a will, nor anything like a blackmail letter, nor even anything remotely suspicious. They’ve spoken to several more of Petersson’s business contacts, but the conversations haven’t produced anything.

And Waldemar and Johan tell them about their latest conversations with the Fagelsjo family, and how they claim that they can hardly remember the accident, and that they managed to get hold of Jasmin Sandsten’s father, Stellan, at work out at Collins Mechanics, but that the conversation gave them nothing except that he had an alibi for the night of the murder. They hadn’t yet had a chance to talk to Jasmin’s mother; she and her daughter were evidently at a rehabilitation home outside Jonkoping.

Zeke on his meeting with Hans Ekstrom.

Grief.

A dead child.

So many years later, perhaps it doesn’t matter much who was driving and whether or not they were drunk.

A child, a cherished child, is dead. Or, possibly even worse, a living death.

Guilt.

Fundamentally meaningless. But can the anger ever end? Forty stab wounds, years of fury unleashed.

Sven quickly explaining the prosecutor’s decision to release Fredrik Fagelsjo. Then: ‘We’ll have to keep an eye on him’, empty words, and he knows it. They don’t have the resources to keep an eye on him.

‘Contacts,’ Waldemar snarls. ‘Who knows what that bastard Ehrenstierna’s got on the prosecutor?’

And Malin thinks about her own work.

The inquiries.

Maria Murvall.

The violence and the hunt for the truth that she imagined might be able to comfort those left on earth when their relative was drifting about in some sort of bright, radiant sky.

‘Did you check your contacts in the underworld?’ Sven asks Waldemar.

‘Looks that way, doesn’t it?’ Waldemar says, and the others laugh cautiously. ‘I checked. But it doesn’t look like Petersson had any connections there.’

And she hears Sven saying that they’ll have to keep digging through Petersson’s life, try to follow the threads of the inquiry as doggedly as possible. Following the lines they already have.

‘We,’ she hears Sven say, ‘are at a stage in the investigation where everything just seems to be spiralling downwards. We might make a breakthrough, or we might get hopelessly stuck. Only hard work can help us now.’

Listen to the voices, Malin whispers quietly to herself.

‘I’m going to Vadstena to talk to Jasmin’s mother.’

‘Soderkoping,’ Sven says. ‘You can go tomorrow, you and Zeke.’

‘I’d like a word with you, Malin.’

Sven’s voice had sounded formal, authoritative, outside the meeting room, and now she’s going up the stairs beside him to his office, and he closes the door behind them and tells her to sit down.

Carved wooden bowls on a white pedestal. Malin knows Sven has made them himself.

She’s sitting in front of him, with him behind his desk with his familiar furrowed face, although Malin can’t quite come to terms with the new wrinkles that have appeared since he lost weight.

There’s a stranger in front of me, and he’s talking to me, he’s worried about me. Don’t worry, Sven, I’m doing enough of that myself, can’t you just leave me alone?

‘How are you feeling?’

‘I’m fine.’

‘I’m not so sure.’

‘I’m fine. Tenerife was great.’

‘So it was good?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you get a bit of sun?’

Malin nods.

‘And you got to see your parents?’

‘I met them. That was nice.’

‘I’ve been – and I still am – worried about you, Malin. You know that.’

Malin sighs.

‘I’m OK. Everything’s just a bit much at the moment. I’ve split up with Janne, and things haven’t settled yet.’

Sven looks at her.

‘And the drinking? You’re drinking too much, that much is obvious just from looking at you. You-’

‘It’s under control.’

‘That’s not what I’m hearing and seeing.’

‘Has someone talked to you? Gone behind my back? Who?’

‘No one’s said a word. I’ve got eyes of my own.’

‘Zeke? Janne? He’s perfectly capable of-’

‘Be quiet, Malin. Pull yourself together.’

After Sven’s stern words they sit in silence facing each other across the room, and Malin knows Sven wants to say something else, but what could he say? It’s not as if I’ve turned up drunk at the station.

Or have I?

‘Has Zeke said anything?’

‘No. I’ve got eyes of my own.’

‘So what now?’

‘You carry on working. But think very carefully before you drive. Let Zeke do the driving. And try to pull yourself together. You’ve got to.’

‘Can I go now?’ Malin asks.

‘If you like,’ Sven says. ‘If you like.’

43

‘Mum?’

‘Tove? I’ve been trying to get hold of you.’

‘I was at school.’

Shall I say I was outside? Will that make her happy? Or sad because I didn’t go in?

‘Are you coming tonight? Did you get my message?’

‘I’m going to the cinema.’

‘Don’t you want to hear how it went at Grandma and Grandad’s?’

‘How did it go?’

‘Tove, please.’

‘OK.’

‘Will you come round after the cinema? You’ve got to. I want to see you. Can’t you tell?’

‘It’ll be late after the cinema. It’s probably best that I get the bus back to Dad’s.’

‘I can make us some sandwiches.’

‘I’ve got all my things out there. I mean, I do kind of live there.’

‘It’s up to you.’

‘Maybe tomorrow evening, Mum.’

‘You know you can live at mine as well. That used to work.’

Tove is silent at the other end of the line.

‘Do I have to beg, Tove? Can’t you come round?’

‘Do you promise not to drink if I come?’

‘What?’ Malin says. ‘I only have the occasional drink. You know that.’

‘You’re incredible, Mum, you know that? Completely messed up.’

And Tove clicks to end the call, and the words linger like nails on her eardrum. Malin wants to get rid of them, shake them out of her ears and hear other, warmer words instead, words that conjure up a different reality, one where she doesn’t lie to her daughter as a way of lying to herself.

Then she sees the monster looming over Tove, ready to kill her, and the monster turns its masked face towards Malin and smiles, whispering: ‘I’m giving you what you want, Malin.’ And at that moment she knows that she drinks largely because she was given a valid excuse when Tove came close to losing her life, that she had the opportunity for an existence that justified her giving in to her greatest passion: intoxication, the soft-edged world without secrets, the world where fear isn’t a feeling but a black cat that you can stroke and whose claws never rip any searing holes in your skin.

Look at me. Poor me. She wants to smash herself into pieces, but most of all she wants to down a glass of tequila.

Where am I?

I’m standing at the entrance of the police station and I’m wondering where to go, Malin thinks as she looks out into the darkness, watching the raindrops turn into grey splinters in the orange glow of the street lamps, as the old barracks change colour in the autumn darkness, turning mute grey instead of matt beige. It’s just gone seven o’clock. The paperwork surrounding her trip to Tenerife kept her working late.

Malin doesn’t move.

Makes a call on her mobile.

He answers on the third ring.

‘Daniel Hogfeldt here.’

‘Malin.’

‘So I can see from the screen. It’s been a while.’

‘You know how it is.’

‘And now you want to meet up?’

‘Yes.’

The doors glide open and three uniformed officers walk past her with quick nods.

‘I don’t take much persuading. Can you come round in half an hour?’

‘Yes.’

She can already feel him inside her as she ends the call.

And exactly thirty-five minutes later Malin is kneeling on all fours on his bed in his sparsely furnished flat on Linnegatan and holding onto the thin metal bedstead as he pumps hard and deep into her and she screams out loud and he is hot and hard and unknown and familiar all at the same time.

He’s like a whip inside me, she thinks.

His hands are sharp barbed wire on my back. She wants to shout: Faster, deeper, you bastard, further in, harder, and it’s as if he can hear her thoughts because he thrusts harder into her each time his body moves and he digs his nails into her neck and she can feel his sweat dripping like cold rain down through her skin and into her flesh and bones and soul.

Don’t resist.

Explode instead.

Let consciousness disappear in pain and beauty, let the little snakes with their many and varied faces retreat to their darkness.

He’s lying on his back beside her on the grey sheet and his toned body stands out against the closed venetian blind. He’s talking, his voice is calm and clear, with all its hardness and warmth intact and she tries to understand what it is he’s asking her.

‘So you’ve split up?’

She’s lying beside him and hears herself reply, with breathless, drifting words.

‘It wasn’t working. I ended up hitting him.’

‘It never works. How could you believe it could?’

‘Don’t know.’

‘What about the Petersson case? Are you getting anywhere? If I were you, I’d take a good look at Goldman.’

‘Sod the case, Daniel.’

His hoarse laughter. And she wants to creep next to him, lay her arms around him, but it’s as if he’s not really there beside her, unless it’s her capacity for closeness that doesn’t really exist?

‘Shall we go another round?’ His hand on my thigh, but I can’t feel it, and his neutral words seem to contain a desire to express something else, as if he had actually been waiting for me, as if he thinks it might somehow be possible to discover something together.

Wasn’t that what we were just doing? Malin thinks.

Then she stands up, gets dressed, and he watches her silently.

‘You’re going?’

Idiotic question.

‘What do you think?’

‘You can stay. I can make some sandwiches if you’re hungry. You look tired, maybe you could do with someone making a fuss of you for a while.’

‘Don’t talk crap, Daniel. I can’t think of a worse suggestion.’

‘Go on, then. The Hamlet’s probably still open.’

‘Shut up, Daniel. Just shut up.’

Zacharias Martinsson has pushed Karin Johannison’s skirt high up over her stomach, he’s pulled off her white nylon tights and carried her through the laboratory in the basement of the National Forensics Lab and put her down on her back on a stainless steel workbench.

She is writhing before him and he is eating her, absorbing her moisture and sweet scent and taste, and he hears her groaning, is that the tenth, the twentieth time now?

Gunilla back at home. No doubt waiting with the evening meal when he called to say he had to work late, that he probably wouldn’t be home until eleven at the earliest.

He tries to bat away the image of his wife alone in the kitchen at home, but it refuses to budge.

He found a reason to pay Karin a visit once last autumn, and she made time for him, leading him down to the laboratory to show him something, and it just happened. They had both been longing for it, and she whispers: Now, come inside, come in Zacharias, and he lifts her down onto the floor, pulls down his trousers and he’s hard and she’s warm and soft and pliable and she looks at him, whispers, My neck’s sweaty, lick the sweat from my neck.

Maria Murvall’s face in front of Malin.

The photo of the bruised rape victim’s face is lying on the parquet floor of the living room, and she twists and turns the image of her own obsession.

Maria.

Your secret.

Preserved within you.

Within your silently screaming body in the white room of Vadstena Mental Hospital, tomorrow I’m going to another hospital, to another mute person.

The bells of St Lars Church strike ten and Malin wonders if Maria is asleep now, and if she is asleep, what would she be dreaming of?

Tove.

Probably on the bus with her friend now.

She won’t come here. And who can blame her, the way I’ve been behaving? I pleaded with her, and she’s probably like everyone else deep down. If they catch a glimpse of weakness, they take the chance to show their own power.

Did I really just think that, about my own daughter?

Malin stops mid-thought, feels shame take a sucking grasp of her body.

Thrusts the thought away.

Who was she going to the cinema with? A boy? How can I let go after what happened? The evil disappears, diminishes in memory over time. Only a hesitant electricity remains as a vague fear, doesn’t it? A fear that can excuse anything.

I don’t understand all this. I don’t understand myself.

And Janne. His warmth like a vanishing dream deep inside a memory. She doesn’t want to talk to him, doesn’t want to ask for forgiveness. What sort of person am I? she wonders. Capable of feeling such derision towards my own love?

Malin goes out into the kitchen and gets the bottle of tequila from the cupboard above the fridge.

Half left.

She raises the bottle to her lips.

What’s this autumn doing to you, Malin Fors? To all of you?

Where is it going to take you?

Look where it took me.

Something you should know: sometimes I’ve felt Andreas close to me, I’ve been able to feel his breath, free from any heat or cold or scent. I haven’t been able to see or hear him, but I know he’s both near me and as far away as he can get.

Jasmin’s here too, part of her.

Should I be scared of them?

Do they wish me harm now?

My world is white. Theirs may be black or grey and cold as the night when the car rolled into the memory of both the living and the dead.

You can’t find out my secret, Malin, and if you did, it probably wouldn’t help you. There’s power in secrets.

My secret?

Uncover it if you want to.

Follow the trail all the way out into loneliness and fear.

Maybe I can have forgiveness then.

If there’s any reason for it.

Forgiveness.

The word zigzags through Janne’s head as he makes a sandwich for Tove, and he looks over at the kitchen worktop where Malin stood screaming just a week ago, where she raised her hand and hit him.

Can you spread forgiveness over time?

How can we approach forgiveness, Malin and me? Because somehow it’s as if we can only do one thing together: feel that we have some sort of debt to each other, that our lives are nothing but an insult, an inadequacy, an injustice that needs to be apologised for.

Have we grown too old, Malin?

How long must an apology be allowed to work between people like us? Twelve years. Thirteen?

Tove likes liver pate with pickled gherkins.

She’s sitting watching television upstairs.

Curled up in its glow.

At home here.

You’re going to want me to apologise for her making that choice, Malin. Aren’t you?

She’s been to the cinema with her friend Frida.

Seems to steer clear of boyfriends, hasn’t really had one since Markus. Since Finspang.

‘The sandwiches are ready, Tove. Do you want herbal or ginger tea?’

No answer from upstairs.

Maybe she’s fallen asleep.

Tove leans back on the sofa and zaps through the channels.

Desperate Housewives. Some reality show. A football match. She ends up watching a documentary about an artist who’s made a sculpture of one of the people who jumped from the World Trade Center, a woman falling to the ground. The sculpture was going to be placed where the towers stood, but people said it was degenerate. Unworthy.

As if they refused to accept that there were people who were forced to jump from the buildings.

She takes a bite of her sandwich.

She couldn’t handle going to see Mum. Not tonight. Tonight she just wants to sit in the darkness and watch television, hear Dad doing whatever he’s doing downstairs.

And the sculpture on television.

A crouching bronze figure. Slight in the wind, just like in the real world. It looks like you, Mum, Tove thinks. And she wants to go down to Dad, ask him to take her home to Mum’s, see how she is, maybe stay there with her. But Dad probably wouldn’t want to do that. And maybe Mum would be cross if they just showed up like that.

Her mobile buzzes.

A text message from Sara. Tove taps a reply as the television shows a close-up of the sculpture’s frightened face, its shimmering bronze hair floating in the wind.