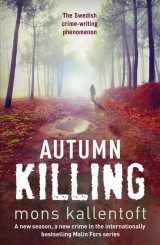

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

31

Sven has left Malin and Zeke alone at their desks.

‘We need to have another word with Goldman again,’ Malin says. ‘Confront him. See what he says.’

‘Call him,’ Zeke says.

Malin dials the number. The phone rings ten times, no answer.

She shakes her head.

‘He could have sent someone,’ Zeke says. ‘We need to find out if any known hitmen have been active.’

‘The book,’ Malin says. ‘Didn’t Segerberg say in the meeting that Goldman’s book had sold badly? Worse than expected? And if they were partners in the business, they would have shared the profits.’

‘So you think Petersson wanted to shop Goldman to create a bit of a buzz about the book? So it would sell better?’

‘Maybe. Sven said that Interpol got the tip-off just before the second book was published.’

‘But why would he do that? He was already rolling in money,’ Zeke says.

‘A lot is never enough,’ Malin says. ‘And business is business. You know, the basic principles.’

‘Like Fredrik Fagelsjo,’ Zeke says. ‘He made a profit to start with, then wanted more, then lost it all.’

‘Greed,’ Malin says. ‘That’s killed a lot of people.’

Books, books, books.

Was it greed that killed me?

Don’t ever go into publishing if you want to earn money.

We printed the second book ourselves, published it through a small company because we thought that would sell better than the first, and why give the money to anyone else? We were as naive about the book as parents are about their children.

But the bastard bookshops hardly ordered any copies, and I used my own money to print fifteen thousand copies, and we needed some serious media attention.

So I called that police officer.

Tipped them off.

But Jochen got away. Presumably tipped off in turn, but I was never worried about him finding out. The detective I called was reliable. And I could always deny it, say that one of Jochen’s closest associates must have betrayed him, because there were still a few of us who knew where he was, in spite of everything.

Shoddy, I know.

But there were articles about Jochen, about how close the police had come to catching him, and the book started to sell, only five hundred copies had to be pulped in the end and we made a small profit.

In business I only had one principle: the bottom line. Practically anything was permissible if it helped a deal go well.

Business is business.

If I couldn’t earn money from Jochen Goldman, what would I want with him? Really? There’s nothing more fleeting than friendship.

But I also know what his anger and self-assurance make him capable of, what doors they can open.

This time Axel Fagelsjo lets them in, invites them to sit down in the sitting room while he goes off to the kitchen to get coffee and cake.

The panels on the walls shine as if they’ve just been varnished.

I wonder if he’s ever seen so much as a picture of a plastic skirting board? Malin wonders as the thickset man comes back with a full tray in his hands.

‘I knew you’d be back,’ he says, serving coffee and shop-bought cinnamon buns. ‘I’m sorry I didn’t tell the whole truth.’

‘Why did you lie to us about the sale of Skogsa, when you didn’t actually want to sell?’ Zeke asks.

‘That’s obvious, isn’t it? It looks fairly compromising for the family, no doubt about that. For Fredrik.’

‘But the fact that you lied doesn’t make it any less compromising,’ Malin says.

Fagelsjo’s goodwill vanishes. Malin sees his face close up, as if the air were going out of his round, pink cheeks.

‘And Fredrik,’ Malin says, ‘why do you think he tried to get away from us? When we only wanted to talk to him.’

‘He was scared he’d end up in prison,’ Axel says. ‘He panicked. No more, no less.’

‘So you don’t think he was out at Skogsa on the morning of that Friday, then? We know he. .’

Axel heaves himself to his feet and stretches to his full height, shouting, throwing the words at them in a fury, drops of coffee and cake crumbs flying through the air.

‘What the hell gives you the right to come here and stir things up? You have absolutely no evidence of anything!’

Zeke’s steel eyes. His gaze boring deep into Axel’s eyes.

‘Sit down, old man. Sit down, and calm down.’

Fagelsjo goes over to the window facing the park and lets his arms drop to his sides.

‘I can confirm everything that Fredrik has told you, that I tried to buy back Skogsa. But we had nothing to do with the murder. You can go now. If you want anything more from me, you’ll have to call me to an official interview. But I promise you, there would be no point in that.’

‘How did it feel, when he turned you down?’ Malin asks.

Axel Fagelsjo stays by the window.

‘Were you angry with Fredrik?’ she goes on, and can see a silent rage taking over the count’s body, and she thinks: You’re not the one who should be angry, Jerry Petersson should be angry, and then she remembers what it was like at high school. There were people like Jerry Petersson there when she was at the Cathedral School, working-class boys who were bloody smart and talented and good-looking, who moved in the smart circles without ever truly being admitted to them, and she remembers that she thought those boys were rather tragic. She kept her distance from all that, she had Janne, but she still daydreamed of belonging to the innermost circle of the lovely, smart and self-proclaimed important students.

‘What were you really doing later that night?’ she asks aggressively. ‘Well? Did you go out to Skogsa to kill Petersson? Or to persuade him once Fredrik had failed? And it all went wrong? And you ended up killing him?’

The words are firing out of Malin.

She wants to lash the old man with her questions, scare the truth out of him. No fucking way I’m going to retreat from someone like you.

‘Or did you pay someone else to do it?’

‘Go now,’ Axel says calmly. ‘The same way you came. I’m tired of this damn Petersson.’

But I’m not tired of you, Malin thinks.

In the stairwell on the way down they meet a reporter and photographer who Malin knows are from the Aftonbladet evening tabloid.

‘Good luck with him,’ Malin whispers after the vultures. ‘Screw him properly.’

Sven Sjoman is eating the salad his wife put in his lunch box that morning.

Crab-sticks and rocket.

An artificial fishy smell hits his nose, reminds him of ammonia. He’s alone in the staffroom, hungry at eleven because he got up so early. The ugly metal chairs look as uncomfortable as they are, and along the long wall of the room hangs a hideous tapestry of Linkoping’s skyline on an autumn day like this one. Disproportionately large crows fly around the spire of the cathedral, and on the roof of Linkoping Castle sits a misshapen grey cat.

Salad is rabbit food.

Not food for a day like today. Today’s real root vegetable weather. Mash, and shiny, fatty pork belly.

He’s told Karim about the call from Interpol, and that Malin tried to call Goldman again.

Sven takes a last mouthful of the salad.

Thinks: What’s best, a short, happy life, or a long, miserable one?

At that moment he finally makes up his mind that a trip will do Malin good, even if it’s questionable that the state of the investigation justifies it. He’ll ask Karim to talk to her about it. That way she won’t be suspicious.

Waldemar Ekenberg walks over to Malin and Zeke as they sit at their desks eating sandwiches they bought at the Statoil petrol station on Djurgardsgatan.

‘Did you get anything out of Axel Fagelsjo?’

Malin shakes her head.

‘There’s something there,’ she says. ‘Something.’

‘You think so? Your female intuition?’ Waldemar says.

Malin gives him a weary look.

‘I wouldn’t mind eating my sandwich in peace,’ and as she says this Karim Akbar comes over to her desk.

He puts a hand on her shoulder, nods to Zeke and Waldemar, before saying: ‘Malin, what would you say to a trip to Tenerife? Have a chat with Jochen Goldman?’

Malin closes her eyes. Lets Karim’s suggestion sink in.

Sun.

Heat.

Mum, Dad, far away from Tove, Janne, all that.

‘What do you say? Put some pressure on him? He’s bound to be there,’ Karim says.

‘I’ll go,’ Malin says quickly. ‘Is this Sven’s idea? Because he thinks I need to get away? That’s it, isn’t it?’

‘You’re paranoid, Malin. The investigation requires you to go. And a bit of sun would do you good,’ Karim says. ‘Anyway, you’ve never been down to visit your parents, have you?’

Malin looks at Karim suspiciously. Gives him a stare that warns him that that’s none of his business.

‘Is Janne home?’ he goes on, and there’s an odd note in his voice, as though he’s dealing with a formality, and it annoys Malin.

She thinks she knows what he’s getting at.

‘Tove can stay. .’ and then she stops herself. Karim doesn’t know that they’ve separated, and he doesn’t need to know. Unless he does know already?

‘Janne can look after Tove,’ she says in the end.

‘Good,’ Karim says. ‘I’ll sort out a ticket for tomorrow. Make sure you’re packed. And be careful. You know what people say about him.’

Malin on her own beside the coffee machine in the staffroom. Holding her mobile. Wants to call Tove but knows she’s at school now, in a lesson, but she has to see her before she goes.

Wants to call Janne. But what would she say? She has to let them know she’s going. Call Daniel Hogfeldt and ask for a serious afternoon fuck session? Creep off to the Hamlet and have a stiff drink? Either of the two last ideas sounds wonderful. But she has to work, then pack.

Should I call Mum and Dad? Let them know I’ll be there tomorrow? Given their attitude to surprises, I’d cause chaos down there. But I ought to phone anyway. I’ll have to see them, even if I don’t want to, I haven’t told them about the separation, that Tove’s still living out at Janne’s, that she hasn’t moved back in yet, unless Janne’s said something, they might have called the house, Dad does that sometimes, but Janne wouldn’t have said anything, would he?

It’ll be nice to get away from this dump for a few days.

In one way, she thinks, you can see Jerry Petersson as the ultimate product of Linkoping, where the inhabitants lose their roots in their desire for money and ridiculous material status. Look at Mum, she’s never managed to have a home where she feels she belongs, I don’t think she has, Malin thinks, and then she thinks about Janne’s house, the flat, and it hurts and she brushes the thought aside, refuses to admit to herself that she’s like her mother in so many ways. Instead she thinks about the fact that you can see Jerry Petersson as the archetypal class traitor, someone who doesn’t know his place, who wants to become something he can never be. A handsome dog that will never win any competitions because he doesn’t have the right pedigree.

I hate the Fagelsjo family, she thinks. Everything they stand for. But I can’t bring myself to hate them as individuals. And she sees Katarina Fagelsjo on her sofa, her eyes, and she wonders where the sorrow in them comes from? Childlessness. Something else?

Malin picks up her coffee and sniffs the black liquid before heading back to her desk.

‘You didn’t get me one?’ Zeke says, looking at Malin’s cup.

‘Sorry,’ Malin says, sitting down as Zeke lumbers off towards the staffroom.

Malin enjoys the hot coffee, feeling the liquid sting her mouth, before she is brought back by Johan Jakobsson’s voice.

He’s holding a bundle of papers towards her.

‘Just got this from the ladies in the archive,’ he says. ‘It turns out that Jerry Petersson was involved in a car accident when he was nineteen. One New Year’s Eve. After a party. He was a passenger, in the front seat. The two in the back seat didn’t get off so lightly. One boy was killed and a girl suffered serious head injuries.’

Malin can’t remember ever hearing any reports of the accident, presumably she was too young to notice when it happened.

‘And do you know what makes it all the more interesting?’ Johan asks.

Malin throws out her hands.

‘The accident happened on Fagelsjo’s estate.’

PART 2

Rain from a cloud that will never return

Ostergotland, October

Eggs hatch.

Blind baby snakes peer out. More and more and more. They make my blood boil.

But let me start here: let’s pretend there’s a film.

A film about a person’s life, where every moment is captured from an illuminating angle.

My film isn’t black, white, or a thousand colours. It’s matt red and sepia-tinted, a slow journey through numbing loneliness.

I see thousands of people in the images.

They flicker past, but never return. Nothing and no one stays, it’s the loneliest of lonely films.

There’s no disgust in the people’s faces, merely, at best, a lack of interest. Most of them don’t see me. I am a person in the form of air, like a fading outline in a shifting landscape. I once had something to cling to, but I’ve taught myself to be free. But did I ever actually manage it? Maybe I just tell myself I did so that I can bear to go on.

And now? After what’s happened? Him, I don’t want to say his name, floating in the cold dark water. I have no illusions about forgiveness or understanding.

But the rage was wonderful. It was as if the snakes left me, ran out of my body and left me calm and powerful. It really didn’t matter what direction it was aimed in, but to say that he didn’t deserve it is wrong. I can do it again if need be, if only to experience once more that feeling of something evil disappearing out of me, the snakes calming down, and me, the person I could have been, should have been, there instead.

It was within me, the violence. And it comes from you, Father, you’re the man in the pictures, you’re hunting me, beating me, you don’t care about the others hunting me, beating me, making me the least significant person in the world, and no one, no one cares, no one comes to my rescue.

Except him. He comes.

The pictures shift.

I have a friend. A proper friend. He saves me.

Sometimes I work this autumn, in spite of what’s hunting me.

I can feel the warm breath of destruction against my neck. No matter what I do, I must protect myself, it’s the only way for us to survive.

They’re hunting me now, trying to find out who I am. But I shall evade them, it must be my turn now. I don’t regret anything, after all, I’ve simply restored a form of order. I possess both the fear of the hunter and of the hunted. In some ways I long for the violence to give me the feeling of calm again, even if I know that’s wrong.

I am all the nuances of loneliness that exist in the world, all the quiet, soundless fear.

Father.

You’re rushing around with your camera, a cigarette glued to your free hand. You raise your bitter, scared hand with nicotine-yellow nails. Strike nimbly at the body lying on the ground. I don’t want to be that body.

But you don’t exist, Father. In a way, I can put even that injustice right. I have been waiting beneath the trees, outside the doors of the heart of evil. Maybe this is my time, after all.

You boys who hate me without me knowing why, without you knowing why. You do not exist.

And then you are gone, you, my rescuer, my friend.

Just like everyone else, you have disappeared.

32

Tuesday, 28 October

‘Viva Las Palmas. Viva Las Palmas.’

The ZZ Top song pops into Malin’s head as she comes down the steps from the plane and heads towards the bus waiting to take her and the other passengers to the arrivals hall.

The sun is sharp and the early afternoon light cuts into her eyes, her throat feels dry and the air is hot on her far too thick sweater. It smells of heat here, sweet and cooked, as if the world were being slowly steamed.

She starts sweating at once.

It must be thirty degrees.

Palms sway alongside gigantic hangars, scorched grass stretches out between the runways, and through the sun-haze Malin can make out a jagged volcanic mountain.

Viva Las Palmas. Vegas. It’s all just a great big game, throw the dice and see where you end up.

But she isn’t even in Las Palmas, she’s at Tenerife Airport, and it strikes her that all these damn islands are the same.

Soon a gaggle of squawking holidaymakers is jostling her in the bus, an exhausted mother holding a sleeping two-year-old in her arms, a gang of teenage boys, already seriously drunk, yelling an IFK Norrkoping football chant.

The bus starts and the cargo of sweaty humanity inside jerks, trying to stay upright even though there isn’t enough space to fall over.

Tiredness and sated longing seeping from people’s pores.

She called Mum and Dad yesterday and could hear the panic in Dad’s voice, no doubt exacerbated by Mum’s presence. ‘What? Coming tomorrow? For work? What sort of work would bring you down here? So you’ll be staying in a hotel? Good, no, I don’t mean that, but we haven’t had time to get anything ready, come over for dinner once you’ve checked in. Pick you up? Tomorrow at two o’clock? Ah, we’ve got a teeing-off time booked at the Abama. You should see the course, Malin, the best on the island, it’s practically impossible to get a round there.’

The bus stops.

Malin gets out, pulls her single heavy case towards the exit.

Outside.

The warmth is suddenly nice, pleasant again now. Not too hot, not too cold, and it’s nice to escape the blasted rain and hail, fired by an angry wind at defenceless faces.

‘Taxi, madam?’

‘Limousine?’

A long line of taxi-drivers is waiting under a white concrete roof.

They’re leaning against their cars, cigarettes dangling from the corners of their mouths, and don’t seem terribly interested in driving her to Playa de las Americas, wherever the hell that is.

She manages to pull the piece of paper out of the front pocket of her skirt, getting even hotter with the effort, and reads the name of the hotel.

She says the name to the taxi-driver she assumes is first in line for a customer, but he gestures towards his colleagues.

A short, fat, bald man further back in the queue of cars raises his arms and waves her over.

‘Taxi?’

Malin nods, and the man takes her case and dumps it unceremoniously in the boot of his white Seat.

She gets in the back.

No air conditioning.

Her top and skirt stick to the black vinyl seat and she realises that the taxi-driver is looking at her expectantly in the rear-view mirror.

‘Where to?’ he says.

‘Hotel Pelicano,’ Malin says, and the taxi-driver frowns anxiously, as though he were suddenly worried that she might not be able to pay.

Twenty minutes later Malin is sitting on an unsteady bed in a small room with small windows in one corner, where a medieval air-conditioning unit is groaning worse than ten decrepit fridges. The grey paint is peeling from the walls, and the yellow plastic floor is covered with cigarette burns.

Rebecka, the new girl in reception at the police station, had booked the hotel, and Karim must have given her an extremely low budget.

There were bars full of prostitutes on either side of the hotel, and it must be at least two kilometres down to the beach at Playa de las Americas, which they drove past on their way here. There was no lobby to speak of, just a shabby desk where an equally shabby man in his mid-forties with greasy hair checked her in with the declaration: ‘Room already paid for.’

Malin gets up from the bed.

She’s longing for a swim. But the hotel hasn’t got anything remotely resembling a pool.

She goes into the bathroom, which is actually pretty clean, but nothing can hide the smell of sewers. A shower cubicle, no bath, and she wants a shower before going to see the local police. They know she’s coming, have offered their assistance.

Malin looks at her face in the mirror.

She conjures up Tove’s face, and thinks that she’s more like Janne, really. She called Tove yesterday, had thought about driving to her school and waiting for her after her last lesson, to take her home and make some food, have a chat, tuck her in, all the things she ought to be doing, but she called instead, afraid that she wouldn’t be able to leave if she met Tove, if she held her in her arms.

She said she had to go away for work, just a couple of days, and Tove snapped: ‘Now you’re doing what Dad does, Mum, going off when everything gets difficult.’

‘Tove, please,’ she heard herself say, and there was something liberating in pleading with her fifteen-year-old daughter, and Tove fell silent, then eventually said: ‘Sorry, Mum. Go. I realise it might be nice to get away.’

‘It’s work.’

‘Where are you going?’

Malin hadn’t planned on telling her. Didn’t want to.

‘Tenerife,’ she said.

‘But that’s where Grandma and Grandad live! I want to come too!’

‘You can’t, Tove. I’ve got to work. And you’ve got school.’

Eighteen months ago Tove would have insisted, maybe shouting down the phone, but now she just kept quiet.

‘Did you help Dad move my things?’ Malin asked.

‘No. He didn’t want me to.’

Then, after another silence: ‘So you’ll be seeing Grandma and Grandad?’

‘I don’t know. Well, we’ve agreed that I might go and see them tomorrow.’

‘You’ve got to see them, Mum.’

‘I’ll say hello from you.’

‘Give Grandad a hug and tell him I miss him. Give Grandma a hug as well.’

Then she calls Janne’s mobile, hoping to get the messaging service, and she does, and leaves a message about going away. He hasn’t called back, so she assumes he doesn’t care.

Malin goes back out into the room, takes all her clothes off, thinking that even if the air conditioning sounds way too loud, at least it works. Then she gets in the shower and turns it on, genuinely surprised at the strength of the water pressure, and lets the water run down her face and body.

She didn’t drink anything on the plane.

And it’s lucky there’s no minibar in the room.

Then Tove comes into her mind again, and Malin wonders why she hadn’t just turned up at the flat or at the station, why she hadn’t insisted on meeting, or even suggested meeting, and she feels the muscles around her ribcage contract as she realises that Tove feels the same ambivalence as she does. You’ve worked out that keeping your distance makes you feel better, haven’t you, Tove?

She pretends to hug Tove. The hot water of the shower is Tove’s warm body.

I’m your mum, and I love you.

The police station is more than a kilometre away, but Malin decides to walk, wearing a thin white dress and a pair of white canvas shoes.

She walks past big hacienda-style villas behind tall, white-plastered walls, newly built terraces, and run-down blocks of flats with washing drying in the windows. She passes hotel complexes where huge pools sparkle behind thin hedges of tropical plants she doesn’t know the names of. A thousand pubs and bars and restaurants screaming out their offerings: ‘Full English breakfast’, ‘Swedish meatballs’, ‘Pizza’, ‘German specialities’.

She wants to look away.

She hopes that Los Cristianos, where her parents live, is a bit more up-market, with a few more redeeming features than the tourist ghetto of las Americas.

The police station is in a cube-like three-storey building on a small square lined with pavement cafes. The sea, shimmering blue in the afternoon light, is visible at the end of a street leading off the square.

Where is everyone? Malin thinks. On the beach?

She pushes open the stiff door of the police station and steps in.

No chairs on the speckled floor of the entrance hall, just a noticeboard on one wall with posters showing the faces of terrorists.

Behind bullet-proof glass sits a young uniformed officer. He’s smoking, gives her a dismissive glance, as if he gets her sort in here all the time.

He must think I’m just another stupid tourist, Malin thinks. Probably thinks I’ve been mugged by Russians. Unless he thinks I’m a prostitute? Could he think that?

Malin goes up to the glass, holds up her police ID.

The policeman raises his eyebrows in an exaggerated, Latin gesture.

‘Aah, Miss Fors, from Sweden. We’ve been expecting you. Let me call for Mr Gomez who will assist you. He’ll be right out.’