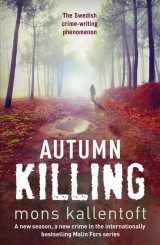

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

46

Sven Sjoman leans back on the wine-red leather sofa in the living room of his villa, pointing at one of the photographs that are spread out on the tiled coffee table. The grandfather clock in the corner has just struck eight, the sound echoing perfectly from the case he made himself. Hand-woven rugs on the floor, large, healthy pot plants hiding the view of the dark garden.

Sven looks at Malin, who is leaning forward in the Lamino armchair opposite him.

She called him, and he told her to come around at once.

The photographs on the table. Carefully laid out with pincers. Sven’s finger in the air.

‘He’s trying to frighten you, Malin. He just wants to scare you.’

And Malin gives in to panic: ‘Tove. What’s to say they’re not going to go for Tove?’

‘Calm down, Malin. Calm down.’

‘It can’t happen again.’

‘Think, Malin. Who do you think’s behind these pictures? What’s the logical answer?’

She takes a deep breath.

In the car she tried to think clearly, force her fear aside.

She ended up back at her first instinct: ‘Goldman.’

Sven nods.

‘This,’ he says, ‘plainly isn’t something we can ignore. But I don’t think you need to worry. It’s just Goldman playing one of those games that he obviously loves so much.’

‘You think so?’

‘Who else could it be? It must be Goldman. He’s playing with us, enjoying the fact that he can scare you. And all the pictures are from Tenerife.’

‘But why?’

‘You’ve met him, Malin. What do you think?’

Jochen Goldman by the pool. The sea and the sky in competing shades of blue, his body down on the beach, the way you were playing with me, getting me where you wanted me. And here: the rain like castanets on the plastic roof of Sven Sjoman’s porch.

‘I think he’s bored. He just wants to show who’s in charge.’

Sven nods.

‘But if there’s any truth in the rumours about what he does to people who get in his way, we have to be careful. Take this seriously.’

‘But what can we do?’ Malin says in a resigned tone of voice.

‘We’ll send the pictures to Karin Johannison. She can check for fingerprints and see if they can find anything else. But I doubt they’ll find much.’

Sven pauses before going on: ‘You don’t think it could be anyone else? Someone you put away who wants to cause trouble?’

In the car on the way to see Sven, Malin had thought through who might want to get back at her. There were a lot of names, but no one she thought would go as far as coming after the police officer who caught them.

Murderers.

Rapists.

Muggers.

A biker gang? Hardly.

But it would make sense to check if anyone had been released and was putting some sort of warped plan into action.

‘Not that I can think of,’ Malin replies. ‘But we should check if anyone I put away has just got out.’

‘OK, we’ll do that,’ Sven says, and his wife comes into the room, says hello to Malin and asks: ‘Would you like a cup of tea? You look half-frozen.’

‘No, thanks, I’m fine. Tea stops me sleeping.’

And Sven chuckles and his wife gives him a curious look, and Sven says: ‘Just a private joke,’ and Malin laughs, feeling it’s the only thing she can do.

‘I’d like a cup,’ Sven says, and his wife disappears into the kitchen and when she’s gone he asks Malin how she is.

He asks the question slowly, in a voice Malin knows he wants to sound both sympathetic and hopeful, and she replies: ‘I had a bit of a slip-up last night. I’m sorry you had to see me like that this morning.’

‘You know I ought to do something?’

‘Like what?’

Malin leans further forward over the table. Asks again: ‘Like what, Sven? Send me to rehab?’

‘Maybe that’s exactly what you could do with.’

And Malin stands up, hissing at him angrily: ‘I’ve just had a threatening letter containing pictures of my parents taken in secret, and you’re talking about rehab!’

‘I’m not just talking about it, Malin. I mean it. Pull yourself together, or I’ll have to suspend you and get you checked in for some sort of treatment before you can come back to work. I’ve got strong grounds to force you to do that.’

Sven’s voice without any softness now, the boss, the man in charge, and Malin sits down again and says: ‘What do you think I should do with Mum and Dad?’

‘It might do you good, Malin. Get you back on track again.’

‘Should I tell them?’

‘Think about it. Once this case is cleared up.’

‘Can we ask the police in Tenerife to keep an eye on them? And on Goldman?’

‘That’s what we’ll do, Malin.’

‘Do what?’

‘Wait and see, as far as you’re concerned. As for the rest, we’ll contact the local police on the Canary Islands. I presume you’ve got a contact there?’

Malin feels the last remnants of the day’s nausea leave her body. Rehab.

Over my dead body.

Got it, Sven?

Not a chance in hell. I was just a bit down. I’m dealing with it, you’ve got to believe me, Sven.

A hand on Sven’s shoulder, a cup of tea on the table in front of him.

‘Your tea, Earl Grey, extra strong, just the way you like it.’

The rain is tapping stubbornly at the car roof.

Her stale breath fills the car as she pulls out her mobile and brings up Jochen Goldman’s number, but there’s no ringing tone, just a bleep followed by a message in Spanish, presumably saying that the person cannot be reached, or that the number is no longer in use, or something equally bloody irritating. Malin clicks to end the call, puts the mobile phone on the passenger seat, and wonders if it’s her or the damp air making the car smell of mould.

She starts the car.

Won’t tell Dad. Or Mum.

She drives home to her empty flat, hoping that she’ll be able to sleep.

Malin can’t sleep. Instead she looks out of the window, at the rain drawing jerky lines on the night sky.

Her body is warm under the covers, calm, not screaming for alcohol or anything else. She dares to allow the extent of her longing for Janne and Tove into the room.

She pulls the covers over her head.

Janne is under there. And Tove as a five-, six-, seven-, eight-, nine-year-old, every age she has ever been.

I love the idea of our love. That’s what I love. Isn’t it?

A knock at the window.

Twelve metres above the ground.

Impossible.

Another knock, the familiar sound of glass vibrating slightly.

She stays where she is. Waits for the sound to stop. Is there something rustling out there? She pulls off the covers. Leaps the few metres to the window.

Rain and darkness. An invisible body drifting above the rooftops?

Drink. Drink.

The words throbbing in her temples now. And then the knocking at the window, three long, three short, like a cry for help from some distant planet.

Am I the one crying out? Malin wonders when she’s back under the covers a few seconds later, waiting for more knocking that never comes.

I’m a long way away from you now, Malin.

But still close.

You know who was knocking, don’t you? Maybe it was me, unless it was just your alcohol-raddled brain playing tricks on you.

Drink, Malin.

Darkness is snapping at your throat and you’ve shown yourself to be weak.

If only for alcohol, money or love.

I myself gave up on love on that New Year’s Eve. After that, I focused all my attention on money. I knew even then, there in my student room in Lund where I can see myself huddled over my law books, that money was the only way I would ever find love. That’s why I so eagerly ran my fingers over the thin, soft paper of those law textbooks.

47

Lund, 1986 and onwards

The young man taps his finger against the silken paper of the law textbook.

He’s got plugs in his ears to shut out all the noise of his corridor in the block for students from Ostergotland in Lund. He uses his implacable blue eyes to photograph the pages of the book. Look, see, memorise. Law is the simplest of subjects for him, words to fix in his memory, and then use as required.

He is in Lund for three years. He doesn’t need any longer to accumulate the points and the marks he needs to serve at the district court in Stockholm. Three years of forgetfulness, to suppress the narrowness of a city like Linkoping, of a school like the Cathedral School, of a life like his has been.

Of course they are here as well, people with surnames that are inscribed with quill pens in the House of Nobility, but less notice is taken of them here.

He scales the facade of the Academic Association’s handsome building one night. Down below the girls stand and scream. The boys scream as well. He travels to Copenhagen to buy amphetamines so he can stay awake and study. He smuggles the pills beneath his foreskin, smiling at the customs officials in Malmo.

He keeps to the edges of the carnival that takes place during his second year. He arrives late at pubs and bars, shows his face, fuelling the rumours about who’s the smartest of all the smart students, about who gets the prettiest girls.

He is merely a body in Lund. Yet also whispers and guesses. Who is he, where does he come from, and one evening he beats up a boy from Linkoping in a car park behind one of the student union buildings. He had told anyone who wanted to know who Jerry Petersson really was: a nobody. A nobody from a nothing flat in a nothing area of a nothing city.

‘You know nothing about me,’ he screams as he stands over the prostrate boy, who is no more than a black shape in the light of a solitary street lamp. ‘So you won’t say anything. You let me be whoever I want to be. Otherwise I’ll kill you, you bastard.’ He leans over, picks up a piece of metal from the ground, holds it like a knife against the boy’s throat, screams: ‘Do you hear this, do you hear them? Do you hear the lawnmower, you bastard?’

He learns all about the female gender. Its softness, its warmth, and that they’re all different and can be transformed in different ways, and that they can act as his chrysalis and give birth to him time after time after time.

He learns what physical longing means as he lies in his student room and dreams about the woman who should have been his, the woman he still dreams will one day be his.

Those dreams are his secret.

The secret that makes him human.

48

It’s getting closer, Malin.

You can feel it in your black dream, spun of secrets.

People who can’t make sense of their lives, who never get to grips with their fear. Crying for help with mute snake voices.

Condemned to wander in misery.

They’re all in your dream, Malin. He’s there, the boy.

Malin.

Who is that, whispering your name?

The world, all human life, all feelings cremated, all snakes slithering around the bloated hairless rats in the overflowing gutters of the city.

Only the fear remains.

The most ashen grey of all feelings.

I want to wake up now.

Maria.

I fell asleep far too early.

Wide awake, Fredrik Fagelsjo thinks as he looks at the bracket clock on the mantelpiece, how its black marble pillars seem to melt into the black stone of the open hearth. The clock is about to strike half past eleven.

Raw weather outside, dry heat in here. Lake Roxen raging wildly just a few hundred metres away.

The fire is crackling, the logs shimmering in tones of orange and glowing grey, the whole room smells of burning wood, of calm and security.

He turns the cognac glass with an easy hand, raising it to his nose and inhaling the aroma, the sweet fruit, and he thinks that he will never drink anything but Delamain. That the last thing he will drink in his life here on earth will be a glass of Delamain cognac.

It was good that Ehrenstierna could use his contacts. Those nights in the cell were terrible. Lonely, with far too much time to think. And he realised something, it came to him as that stuffy old superintendent was going on about his family, about Christina and the children. He realised that the money and Skogsa and all that crap really didn’t matter at all. He’s got all that matters here, and Christina, their socially unequal love, and the children, are everything. What they have works, even if Christina has never got on with Father, even though she’s become one of them as the years have passed.

The children. He’s neglected them to get what he thought he wanted, what Father wanted.

I’ll have to cope with a month in Skanninge Prison next summer. I can do it. I know that now.

Christina and the children are staying with his parents-in-law. It was arranged long ago, and no time in custody would change that, they had agreed on that. But he would stay at home. Enjoy the Villa Italia in the autumn darkness.

They ought to be home soon.

Fredrik Fagelsjo loves the peace and quiet of the villa on an evening like this, but he’d quite like to hear the sound of the car pulling up now.

Hear the children rush up the steps in the rain.

Their footsteps.

Fredrik pours himself another cognac.

They’re still not back, and he wants to call his wife, but holds back the urge. They’ve probably just stayed to watch a film or they’re playing a game, one of those common parlour games that his mother-in-law, terrible woman, loves.

The castle.

It’s part of a dead man’s estate now, belongs to Petersson’s father. The police haven’t tracked down any other rightful heirs, but they’ve still got the money, thanks to some old bag in a branch of the family that they’ve never had anything to do with. Money that’s leaped out of their history.

Father’s going to make an offer.

The natural order restored.

Because who should live at Skogsa if not us? Even if it isn’t really that important, it’s ours. And we need to pass it on.

Jerry Petersson.

Someone who moved out of his class. Who didn’t know his place, who never knew his place. That’s the simple way of looking at it, Fredrik thinks.

He was drowned in his own ambitions.

A solicitor named Stekanger is in charge of his estate. A good, quick offer and the matter will be dealt with, if Petersson’s father accepts it. If he refuses, we’ll raise the offer a little. The land is ours, and no kids except mine will get to play there, I feel that very strongly, against my own inclinations.

Then I’ll get to grips with the farming. Grow crops for biofuel and make the family a new fortune. I’ll show Father I know how it works, that I can create things and make them happen.

That I can be ruthless. Just like him.

That I’m not just a bank official who’s only good at losing money, that I can carry the family into the future.

Fredrik feels his cheeks burn as he thinks of the stock options, the losses, and how incredibly stupid he has been.

But now there’s money again.

I’ll show Father I’m good enough to have my portrait on the wall at Skogsa. And once I’ve shown him, I’ll tell him that his opinion of me doesn’t mean anything, that he can take his portrait and go to hell.

He gets up.

Feels the parquet floor sway beneath his feet as the cognac goes to his head.

He sits down again. Looks at the picture of his mother, Bettina, beside the clock. Her gentle face enclosed by a heavy gold frame. How Father has never been the same since she went. How he seems almost lost, left behind.

Fredrik was eavesdropping outside his mother’s sickroom at the castle during her last night of life. Heard how she made Father promise to look after him, their weak son.

His mother wasn’t at all like that female detective who arrested him out in the field after he tried to get away from the police in the city, yet Fredrik finds himself thinking about her for some reason.

Malin Fors.

Quite good-looking.

But trashy. Bad taste in clothes and far too worn-out for her age. She’s got that cheap look that all country girls from poor families have. What distinguished her from others like her was that she seemed completely aware of who she was. And that it bothered her. Maybe she’s intelligent, but she could hardly be properly smart.

Are you going to be back soon?

The old villa seems to have secrets in every corner, and the damp and rain are making the house creak, as if it’s trying to send him a message in Morse code.

Then Fredrik hears something.

Is that the car pulling up, his wife’s black Volvo? The clock strikes. Of course, it must be them. The children are probably asleep in the car now, if they were going to be spending the night with her parents Christina would have called.

He gets up.

Walks unsteadily out into the hall where he opens the double doors.

The rain is driving against him, but he can’t see any sign of a car in the drive.

Solid darkness outside.

And the rain.

Then a pair of car headlights come on over by the barn.

Then they go off again.

And on again, and he can’t see the car well enough to see what model it is, but it looks like it’s black, it is, and he wonders why his wife doesn’t drive right up to the house in weather like this, maybe the damp has caused engine trouble, and he steps out onto the porch and waves, and the headlights flash again, over and over again. His wife and children. Do they want him to run over with an umbrella? Or is it his father? His sister?

Flash.

Flash.

Fredrik pulls on his oilskin.

Opens the umbrella.

Flash.

Then darkness.

He heads through the rain towards the car, which now has its lights off, maybe fifty metres away.

Darkness.

He can almost feel his pupils expand, his eyes working feverishly to help his brain make sense of the world, as if the world disappears without the right signals.

He should have switched on the garden lights. Should he go back?

No, carry on towards his wife and kids.

He’s approaching the car.

His wife’s car.

No.

Tinted glass, impossible to see through.

Something moving inside the car.

An animal?

A fox, a wolf?

A quick sound from whatever it is that’s moving.

And Fredrik goes cold, his body paralysed, and he wants to run like he has never run before.

It’s only a dream, Malin thinks. But it never seems to end.

Fear only exists in the dream.

Something knocking deep inside me.

The fire, the fire I shall one day go into, is nothing to be afraid of.

I’ve given in. And that frightens me.

What I am, is my fear. Isn’t that right?

PART 3

The carefree and the scared

Ostergotland, October

The film doesn’t stop just because I want it to.

It’s endless, and the images become more and more blurred, indistinct, grey, as their edges smoulder.

No matter what happens, they won’t catch me.

I shall defend myself.

I shall breathe.

I won’t hold back any of the rage. I shall let the young snakes, the last of them, leave my body.

I have to admit that it felt good this time. It wasn’t a sudden outburst like the first time. I knew what I was going to do. And there were a thousand reasons. I saw your face in his, Father, I saw all the boys in the schoolyard in his face. I undressed him like they undressed me, I pretended I was laying him on an altar of young snakes.

It made me calm, the violence. Happy. And utterly desperate.

The darkness is getting thicker now, the raindrops are balls of lead crashing onto the ground, onto the people.

It’s my turn now. I’m the most powerful.

No one will ever again be able to turn away from me. And who really needs those pigs with their traditions, names, the sense of superiority they acquire at birth. The pictures flicker, black and white with pale yellow numbers. The story of me, the one firing out of the projector, is approaching its end now.

But I am still here.

Father embraces me again in the pictures, and he’s thin, and Mum won’t survive the cancer for much longer. Come to me, son, stand still so I can hit you.

I have a friend.

It’s possible to escape loneliness, captivity. The strangers and the fear, all the things that are unbearable. Life can be a blue, mirror-calm sea.

Money.

Everything costs.

Has a price.

The boy sitting in the garden in the pictures on the white projector-screen doesn’t know that yet, but he has a sense of it.

Money. It should have been my turn.

Father, you have no money. You never have had. But why shouldn’t I? Your bitterness isn’t mine, and maybe we could have done something together, something good.

But things went the way they went.

A rented flat, a terraced house, feeble little abodes.

I am running alone through the garden in the pictures. The devil take anyone who creates loneliness, and the fear that comes with it.

The devil take them.

Boys. Living and dead, men with skins to try to fit into.

Then the reel ends. The projector flashes white. Neither the boy nor the man is visible any longer.

Where should I go now? I’m scared and alone, a person who doesn’t exist in any pictures. All that is left is the feeling of young snakes crawling beneath my skin.