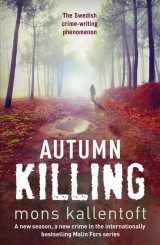

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

3

Mum.

You’re so angry, Tove thinks, as she pulls the covers over her head and listens to the rain clattering on the roof, hard and fierce, as if there were an impatient god up there drumming millions of long fingers.

The room smells of the country. She was just looking at the rag-rugs, resting like flattened snakes on the floor, their pattern like a beautiful series of black-and-white pictures that no one will ever be able to interpret.

I know, Mum, Tove thinks. I know you blame yourself for what happened last summer, and that you think I’m bottling up all sorts of things. But I don’t want to talk to a psychologist, I don’t want to sit there babbling opposite some old lady. I’ve been chatting to other people on trauma.com instead. In English. It’s as if it all gets easier when I see my own clumsy words about what happened, and about how scared I was then. The words take the fear away, Mum, I’ve only got the images left, but the images can’t get me.

You have to look forward, Mum. Maybe you think I haven’t seen you drinking. That I don’t know where you hide the bottles around the house, that I don’t notice that your breath smells of alcohol behind the mask of chewing-gum. Do you think I’m stupid, or what?

She and Janne had remained at the kitchen table when Malin disappeared with all her rage.

Janne had said: ‘I hope she doesn’t crash the car and kill herself. Should I call the police? Or go after her? What do you think, Tove?’

And she hadn’t known what to say. Most of all she wanted her mum to come back, to rush into the kitchen in her very best mood, but things like that only happened in bad books and films.

‘I don’t know,’ she had said. ‘I’ve no idea.’

And her stomach had been aching, as far as her chest, a black pressure that wouldn’t let up, and Janne had made sandwiches, had told her things would sort themselves out once her mum had calmed down.

‘Can’t you go after her?’

And Janne had looked at her, then simply shaken his head in response. And the ache had found its way up into her heart and head and eyes, and she had to struggle to hold back the tears.

‘It’s OK to cry,’ Janne said, sitting down beside her and holding her. ‘It’s awful. It’s awful, because no one wanted it to turn out like this.’

‘It’s OK to cry,’ he had said again. ‘I’m going to.’

How can I help you, Mum? Because no matter what I say it’s like you’re not listening, don’t want to listen, like you’re trapped in an autumn river full of dirty torrential water and you’ve made up your mind to float off into the darkness.

I can see you in the kitchen, on your way to work, in the mornings, on the sofa in front of the television, or with all your files about that Maria woman.

And I want to ask you how you are, because I can see you’re feeling bad, but I’m scared you’d just be angry. You’re completely shut off, Mum, and I don’t know how to get you to open up.

And there’s so much else that I’d rather think about: school, my books, all my friends, all the fun stuff that I feel I’m just at the start of. All the boys.

Tove pulls the covers down. The room is there again.

The ache in her stomach, her heart, is still there. But for me it’s quite natural that you don’t live together, you and Dad. And there’ll be more fighting. Because I don’t think you’re coming back here, and I don’t know if I want to live with you now.

A crow has landed on the windowsill. It looks in at her. It pecks at the glass before flying off into the night.

The room is dark.

‘I’ll be fine,’ Tove thinks. ‘I’ll be fine.’

Janne is lying in bed with one of the bedside lamps on. He’s reading a folder from the British Armed Forces. It’s about building latrines, and it helps him to find his way into his memories, to Bosnia, Rwanda and Sudan, where he most recently constructed latrines in a refugee camp. The memories from his time in the Rescue Services Agency mean that he can avoid thinking about what happened this evening, about what has happened, and now must happen.

But the images, black and white in his memory, of people in desperate need in distant corners of the planet, are constantly shoved aside by Malin’s face, her red, puffy, tired, alcoholic’s face.

He confronted her several times. And she evaded the issue. Yelled at him when he poured away the drink from the bottles she’d stashed away, screaming at him that it was pointless, because she still had ten bottles hidden in places he’d never find.

He pleaded with her to see someone, a psychiatrist, a therapist, anyone at all. He had even spoken to her boss, Sven Sjoman, telling him that Malin was drinking more and more, but that it might not be visible at work, and asking him to do something. Sven had promised that something would be done. That conversation had taken place in August, but nothing had happened yet.

Her rage. Against herself. Presumably because of what happened to Tove. She refused to accept that it wasn’t her fault, that there is evil everywhere, always, and that anyone can get in its way.

It’s as if her stubbornness has led her in the wrong direction. That she’s absolutely committed to driving herself as far down as she can go.

And tonight she hit him. She’s never done that before.

Dig deep. Dig deep.

Regular check-ups. Bacteria sanitation.

Janne throws the files across the room. Turns out the light.

It was pretty stupid, really, he thinks. To imagine that a bloody terrible experience could make us work together as a family. As if evil could be a catalyst for good. In truth the complete damn opposite has happened.

Then he looks at Malin’s side of the bed. Reaches out his hand, but there’s no one there.

4

Sleepless dawn.

Axel Fagelsjo is about to get up from his leather armchair, but first he rubs his fingers over the worn, shiny armrest and stubs out his cigarette in the ashtray on the leather-topped sideboard. Then he lets his legs take the weight of his heavy yet still strong seventy-year-old body and pulls in his stomach, feeling strangely powerful, as if there were some enemy outside the door that he needs to fight with one of the many hunting rifles in the cabinet over in the apartment’s master bedroom.

Axel stands in the sitting room. He sees Linkoping wake up outside the windows, imagines its inhabitants in their beds, all those people with their different lives. Anyone who says there’s no difference between people doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

The trees in the Horticultural Society Park, their crowns blown this way and that by the wind. Only gentle rain now. Not the sort of downpour that drives the rats out of the sewers. That’s happened several times this autumn. And the city’s pampered middle classes have been horrified by the beasts nurtured in subterranean Linkoping. As if they refuse to accept that there are rats living beneath their well-shod feet. Rats with hairless tails and razor-sharp teeth, rats that will still be there long after they themselves are gone.

It’s been a long time since he slept through the night. He has to get up at least three times to go to the toilet, and even then he has to stand there for five minutes before releasing the little trickle that made him so incredibly desperate to go.

But he doesn’t complain. There are people with far worse ailments than him.

He misses Bettina when he wakes up at night. Only an empty white bed where she was always contours, warmth and breath. As luck would have it, she went before the catastrophe, before Skogsa slid out of his grasp.

The castle was at its most beautiful on mornings like this.

He can see the castle within him, as though he were standing in front of it, at the edge of the forest.

The seventeenth-century grey stone walls seem to rise up from the fog, more potent than nature itself.

Skogsa Castle. Constructed and altered over the years according to the eccentric whims of his ancestors.

The copper roof seems to glow even when the sky is covered by low cloud, and the countless eyes of the building, the old castle’s loopholes and the more recent lead windows. He has always imagined that the loopholes were watching him from a distant moment in history, measuring him against his predecessors as master of the castle. The new windows are blind by comparison, as if looking for something lost.

From this viewpoint in his memory he can’t see the chapel, but it’s there. Bettina isn’t there, however – she had wanted him to spread her ashes in the forest at the north of the estate.

He can hear them.

The fish splashing uneasily in the black water of the moat, maybe the dead Russian soldiers, the hungry, walled-in spirits, are nipping at their gills.

Count Erik Fagelsjo.

A robber baron during the Thirty Years War. A favourite of Gustav II Adolf, the most brutal warrior of all, said to have mutilated twenty men in one day during the skirmishes following the Battle of Lutzen. Count Axel Fagelsjo thinks: I have always felt that man’s blood flowing through my veins.

In his youth he wanted to serve with the UN. But his father said no. His father, the friend of Germany, the colonel who had gone around Prussia in the thirties fawning over the blackshirts, the castle-owner who believed in a German victory long into the early 1940s.

And now?

After what had happened.

Count Erik Fagelsjo must be spinning with shame in the family vault in the chapel at Skogsa, lying there naked and shrieking with utter fury.

But there’s still a chance, if it weren’t for that useless dandy, that bastard who came slithering down from Stockholm like a legless lizard.

Axel Fagelsjo looks out across the park again. Sometimes this autumn he has imagined he can see a man under the trees, a man who seemed to be peering up at his windows.

Sometimes he’s thought it was Bettina.

He talks to her every day, has done since she died three years ago. Sometimes he goes out to the forest where he scattered her ashes, hiking there no matter what time of year, most recently through mouldering fiery yellow leaves and swaying mushrooms, his dark voice like an echo between the trees, trees that seemed almost rootless, floating.

Bettina.

Are you there? I never thought you’d go first. I miss you, you know. I don’t think anyone knows, not even the children, how much I love you, loved you.

And you answer. I can hear you telling me that I must be strong, not show what I feel, you see what happens if you give in. Axel, the wind whispers, and the wind is your voice, your breath against my neck.

Bettina.

My Danish beauty. Refined and unrefined at the same time. I first saw you in the summer of 1958, when I was working as a foreman at the Madsborg estate on Jutland, there to get some experience of farming.

You were working in the kitchen that summer. A perfectly ordinary girl, and we would swim in the lake together. I’ve forgotten the name of the lake, but it was on the estate, and I brought you back home after that summer and I remember Father and Mother, how they were dubious at first, but gradually gave in to your charm, and Skogsa succumbed to your cheerful temperament.

And you, how could you, Bettina? How dare you give in to cancer? Were you sad that our income wasn’t enough to keep the castle in good condition? It would have eaten too much into our capital, all the millions that were needed.

I don’t want to believe that. But I can feel guilty, the guilt you feel when you hurt the person you love most of all.

Pain. You had to learn all about pain, and you told me there was nothing worth knowing in those lessons.

The paintings on the walls here are your choices. Ancher, Kirkeby. And the portrait of my ancestor, Erik, and all the other wonderful fools and madmen who went before me.

You died at the castle, Bettina. You would have hated having to leave it, and I’m ashamed for your spirit now. No matter how gentle you could be, you could be just as hard when it came to defending what was yours.

Most of all you worried about the boy.

Among your last words: ‘Look after Fredrik. Protect him. He can’t manage on his own.’

Sometimes I wonder if he was listening at the door of your sickroom.

You never know with him. Or maybe don’t want to know. Like everyone else, I love my daughter, and him, my son. But I’ve always been able to see his shortcomings, even if I didn’t want to. I’d rather have ignored them and seen his good qualities instead, but that doesn’t seem to be possible. I see my son, and I see almost nothing but his failings, and I hate myself for it. Sometimes he can’t even seem to control his drinking.

The clock on the bureau strikes six and Axel stops by the sitting-room window. Something breaks out of the darkness below and someone walks through the park. A person dressed in black. The same man he thought he saw earlier?

Axel pushes the thought aside.

I knew it was a mistake, he thinks instead. But I still had to do it: letting Fredrik, my firstborn, the next Count Fagelsjo, look after our affairs, giving him access to our capital when my soul turned black after the cancer won. He never wanted to be at the castle, never wanted to manage the small estate and forest that were left, because it was now more profitable to take the EU subsidies for set-aside land than rent it out.

Didn’t want to. Couldn’t. But he ought to have been able to handle the money.

He’s got financial qualifications, and I practically gave him free rein.

But everyone has their good and bad sides, their faults and shortcomings, he thinks.

Not everyone has enough of the predator in them, enough of the merciless power that seems to be needed in this world. Father tried to get me to appreciate the responsibility that comes with privilege, how we have to assume a position of leadership in society. But in some ways he belonged to a bygone age. Certainly, I led the work out at Skogsa, I was respected in the finer society of the region, but a leader? No. I tried to get Fredrik and Katarina at least to appreciate the value of privilege, not to take it for granted. I don’t know that I succeeded.

Bettina, can you tell me what I can do to make Katarina happy? And don’t try that same old tune again. We had different opinions about that, as you know.

Be quiet, Bettina.

Be quiet.

Let me put it like this: Was the bloodline diluted with you, Bettina?

He has sometimes wondered this when looking at Fredrik, and Katarina too, occasionally.

The green Barbour jacket sits tightly across Axel Fagelsjo’s stomach, but he’s had it for twenty-five years and doesn’t want to buy another one just because the kilos stick a bit more easily than they used to.

Things must run their course, he thinks as he stands in the hall.

We Fagelsjos have lived more or less the same way for almost five hundred years. We set the tone for the area, for this city.

Sometimes he thinks that people around here are imitating the life he and his family have always had. The first water closet in Ostergotland was at Skogsa, his grandfather wore the first three-piece suit. They have always shown the way, and the business and political communities understood this, even if that’s all history now.

There was no invitation to the county dinner this year.

In all the years that the county governors held dinners for the most prominent people in the county, there has always been a Fagelsjo among the guests. But not this year.

He saw the picture taken at Linkoping Castle in the Ostgota Correspondent. Count Douglas was there. The historian Dick Harrison. The director of Saab’s aviation division. The head of information at Volvo. A parliamentary under-secretary with roots in the city. The editor-in-chief of the Correspondent. The Chair of the National Sports Association. Baron Adelstal.

But no one from the Fagelsjo dynasty.

He pulls on his thick black rubber boots.

I’m coming now, Bettina.

The calfskin gloves. What leather!

Axel thinks that things will probably sort themselves out anyway. Hears Bettina’s voice: ‘Protect the boy.’

I did protect Fredrik. I did what was necessary, even if, in theory, the bank could have been held responsible.

The memory of Bettina’s face fades.

Maybe I should have let things go to hell with the boy, Axel thinks, as he presses the cold button of the lift to go downstairs and out into the lonely dawn.

5

No other engine sounds like that of the Range Rover: elegant yet powerful. And the vehicle responds nicely when Jerry Petersson presses the accelerator. Maybe that was how the horses of former centuries responded when long-dead counts pressed their spurs to the flanks of their sweating steeds.

No horses here now.

No counts.

But he can always get a few horses if he meets a woman who likes them, they have a tendency to like horses, women. Something of a cliche, but this cliche was also a reality, like so many others.

Jerry Petersson sees banks of fog drifting in across the fields, coming to rest beside the pine forest over to the east. The dog is sitting beside him in the passenger seat, letting its perfectly balanced body move in time with the vehicle’s suspension, its eyes searching the landscape for something living to chase after, stand over, help to bring down. Jerry Petersson runs a hand through its coarse, damp fur. It smells, the dog, but it’s a smell that suits the countryside, with its raw, penetrating authenticity. A beagle, a male, that he has named Howie after Howard Hughes, the Hollywood madman of the thirties who is said to have founded the modern aviation industry, and who, according to legend, ended up a recluse in a castle outside Las Vegas, dependent on blood transfusions.

Jerry once read a biography of him and thought: if I ever buy a dog, I’m going to name him after an even bigger madman than me.

The dog’s nostrils contract, open again, and its big black pupils seem to want to devour the land around Skogsa.

The estate is never more beautiful than in the morning, when the approaching day seems to soften the earth and rocks. Rain is falling against the windscreen and roof and he stops the car at the side of the road, watching some birds hopping about on the oyster-shell coloured soil, pecking for worms in the rotting vegetation and the pools that are growing larger with each passing day. The leaves are lying in drifts here, and he thinks they look like a ragged cover in a beautiful, forgotten sketch for an oil painting. And under the cover life goes on. Grubs pupating. Beetles fighting each other. Mice swimming in streams of rain towards goals so distant that they can’t even dream they exist.

The dog is starting to get anxious, whimpering, wanting to get out, but Jerry soothes it.

‘There now, calm down, you can get out soon.’

A landscape.

Can that be a person’s fate?

Sometimes, when Jerry drives around the estate, he imagines he can see all the characters that have come and gone in his life. They drift around the trees, the rocks and buildings.

It was inevitable that he would end up here.

Wasn’t it?

Snow falling one New Year’s Eve, falling so thickly it makes this morning’s fog look as transparent as newly polished glass.

He grew up not far from here.

In a rented flat in Berga with his parents.

Jerry looks at himself in the rear-view mirror. Starts the engine and drives on.

He drives around two bends before stopping the car again. The dog is even more restless now, and Jerry opens the door, letting the dog out first before getting out himself. The dog races off across the open field, presumably chasing the scent of a deer or elk, or a hare or fox.

He looks out over the field for a while before stepping down onto the soft ground. He trudges about, watching the dog running back and forth along the line of the forest, leaping into a deep ditch before reappearing only to vanish into a pile of leaves where the faded ochre-colours compete for attention with others that seem to be powdered matt bronze or dull gold.

Apart from the dog, Petersson is completely alone out in the field, yet he still feels quite at ease here, in a place where everything can die yet also be born, a breaking point in people’s lives, a sequence of possibilities.

He runs his hand through his bleached hair, thinking how well it suits his sharp nose and hard blue eyes. The wrinkles in his brow. Business wrinkles. Well-earned.

The forest over there.

Fir trees and pines, undergrowth. A lot of game this year. His tenant farmers are coming later today, they’re going to try to get a young elk or a couple of deer. Something needs be killed.

The Fagelsjo family.

What wouldn’t they give for the chance to hunt in these forests again?

He looks at his arms, at the bright yellow Prada raincoat, the raindrops drumming on his head and the yellow GORE-TEX fabric.

‘Howie,’ Petersson calls. ‘Howie. Time to go now.’

Hard. Tough. An ice-cold machine. A man prepared to step over dead bodies.

That was how people talked about him in the business circles he moved in up in Stockholm. A shadow to most people. A rumour. A topic of conversation, something that was often the cause of admiration in a world where it was deemed desirable to be so successful that you could lie low instead of maintaining a high profile, instead of appearing on television talk shows to get more clients.

Jerry Petersson?

Brilliant, or so I’ve heard. A good lawyer. Didn’t he get rich from that IT business, because he got out in time? Supposed to be a real cunt-magnet.

But also: Watch out for him.

Isn’t he involved with Jochen Goldman? Don’t they own some company together?

‘Howie.’

But the dog doesn’t come, doesn’t want to come. And Jerry knows he can leave it be, let the dog find its own way home to the castle through the forest in its own good time. It always comes home after a few hours. But for some reason he wants to call the dog back to him now, come to some sort of arrangement before they part.

‘Howie!’

And the dog must have heard the urgency in his voice, because it comes racing over the whole damn field, and is soon back with Jerry.

It leaps around his legs, and he crouches down beside it, feeling the damp soak through the fabric of his trousers, and he pats the dog’s back hard in the way he knows it likes.

‘So what do you to want to do, eh, boy? Run home on your own, or drive back with me? Your choice. Maybe run back on your own, you never know, I might drive off the road.’

The dog licks his face before turning and running back across the field and hiding under a pile of leaves, before disappearing through the dark, open doors of the forest.

Jerry Petersson gets back in the Range Rover, turns the key in the ignition, listens to the sound of the engine, then lets the vehicle nose its way along the road again, into the dense, fog-shrouded forest.

He hadn’t locked the castle doors when he set off on his spontaneous morning drive around the estate after waking early and being unable to get back to sleep. Who was likely to come? Who would dare to come? A hint of excitement: I bet they’d like to come.

Fredrik Fagelsjo. Old man Axel.

Katarina.

She’s stayed away.

The daughter of the house.

My house now.

He moved in their orbit a long time ago.

A crow flies in front of the windscreen, flapping its wings, one wing looks injured somehow, maybe broken.

The castle is large. He could do with a woman to share it with. I’ll find one soon enough, he thinks. He’s always thought, in his increasingly large homes, that he could do with a woman to share it with. But it was merely a mental exercise that he enjoyed playing, and whenever he really needed a woman it was easy enough for someone like him: go to a bar, or call one of the numbers, and love would arrive, home delivery. Or a randy housewife in the city for a conference. Whatever. Women to share the present moment, women without any connections either backwards or forwards in time, women as desire-fulfilling creatures. Nothing to be ashamed of. Just the way it is.

He’d heard a rumour that Skogsa was for sale.

Sixty-five million kronor.

The Wrede estate agency in Stockholm was handling the sale. No adverts, just a rumour that a castle with a vast estate was for sale in the Linkoping area, and perhaps he might be interested?

Skogsa.

Interested?

Sixty-five million stung. But not much. And he got more than the castle for his money. Seventy-five hectares of prime forest, and almost as much arable land. And the abandoned parish house that he could always pull down and replace with something else.

And now, here, on this beautiful black autumn morning, when the fog and the relentless rain and the feeling of lightness and of being at home fill his body, he knows it was money well spent, because what is money for if not to create feelings?

He wanted to meet Fagelsjo when the deal was concluded in the office on Karlavagen. Didn’t exactly want to smirk at him, but rather give him a measured look, force the old man to realise how wrong he had been, and let him know that a new age had dawned.

But Axel never showed up at the meeting in Stockholm.

In his place he sent a young solicitor from Linkoping. A young brunette with plump cheeks and a pout. After the contract was signed he asked her to lunch at Prinsen. Then he fucked her upstairs in his office, pushing her against the window, pulling her skirt high up her stomach, tearing a hole in her black tights and pumping away, bored, as he watched the buses and taxis and people moving in a seemingly predetermined stream down Kungsgatan, and he imagined he could hear the sound of the great lawnmowers in Kungstradgarden.

The castle is supposed to be haunted.

The unquiet spirit of a Count Erik who is said to have beaten his son to death when the son turned out to be feeble-minded. And the Russian soldiers who were supposed to have been walled up in the moat.

Jerry has never seen any ghosts, has just heard the creaking and sighing of the stone walls at night, feeling the chill that has been stored up in the old building over the centuries.

Ghosts.

Spirits.

The castle and outbuildings were run-down so he’s had everything renovated. This past year he’s felt like a foreman on a building site.

Several times he’s seen a black car on the estate and assumed it was one of the Fagelsjo family getting a kick of nostalgia. Why not? he reasons. Mind you, he doesn’t know for sure that it is one of the family, it could be pretty much anyone, there are certainly people who’d like to visit.

He was profiled in the Correspondent when it became known that Skogsa had a new owner. He gave an interview, mouthed humble platitudes about fulfilling the dream of a lifetime. But what good had that done?

The journalist, a Daniel Hogfeldt, went for the shady-business-dealings angle, and made out that he had forced the Fagelsjo family from their ancestral home of almost five hundred years.

Whining.

Stop whining. No birthright gives anyone a lifetime’s right to anything.

To this day, the article annoys him, and he regrets giving in to his vanity, his desire to send a message to the area that he was back. To recreate something that never existed: that was what he imagined he was doing.

How much damage have the Fagelsjo family done to people around here, though? How many peasants and tenant farmers and wage-slaves have had to endure their bailiff’s whip? How many people have been trampled underfoot by the Fagelsjos’ assumption that they’re better than everyone else?

Petersson hasn’t taken on any employees, instead he contracts people whenever anything needs doing, and he’s careful to make sure he pays them well and treats them decently.

And the story of the moat around the castle. That it was built in the early nineteenth century, long after anyone in this country had any need of a moat. That one of the counts got it into his head that he wanted a moat, and commandeered a load of Russian prisoners-of-war from von Platen’s work on the Gota Canal and worked them until they dropped, a lot of them dying of exhaustion. It was said that they interred the bodies in the walls of the moat when they lined it with stone, that they shut those Russian souls in for all eternity for the sake of a meaningless moat.

But sometimes it feels a bit isolated at the castle. And for the first time in his life he has felt that he could do with a friend. The security of having another living creature around him, someone who would take his side no matter what happened, who would sound the alarm if there was any danger approaching. And a dog was useful for hunting.

Is that something up ahead on the road? Howie? Back so soon. Impossible. Completely impossible.

A stag?

A deer.

No.

The rain is pouring down now, but inside the oil-smelling warmth of the Range Rover the world seems very agreeable.

Then the castle appears out of the fog, its three storeys of grey stone seeming to force their way out of the earth, the leaning walls straining towards the grey sky, as if they thought they should be in charge up there. And the light from the swaying green lanterns he has had installed along the moat. He loves the brightness they give.

Is that someone standing on the castle steps?

The tenant farmers he’s going hunting with aren’t due until later on, and they’ve never been on time yet.

He accelerates.

He feels with his hand beside him for the dog, but the warm fur isn’t there.

Of course.

Petersson wants to get there quickly, wants to hear the gravel of the drive crunch under the Range Rover’s tyres. Yes, there is someone on the steps.

The outline of a figure. Hazy through the fog. Unless it’s an animal?

The castle ghosts?

The vengeful spirits of the Russian soldiers?

Count Erik paying him a visit with his cloak and scythe?

He’s ten metres away from the black shape now.

Who is it? A woman? You?

Can it really be that person again? Certainly persistent, if it is.

He stops the car.

Blows the horn.

The black figure on the steps moves silently towards him.