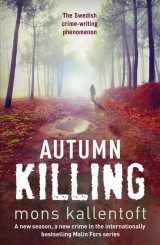

Текст книги "Autumn Killing"

Автор книги: Mons Kallentoft

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

57

‘He dragged me to the ground and whipped me. My back was stinging like it had been burned from the cracks of the whip, and when I turned round to get up the whip caught my eye.’

Another voice in the investigation’s choir.

Malin and Zeke are each sitting in an armchair in Sixten Eriksson’s flat in a block of sheltered housing, Serafen. From his living room he has a view of the Horticultural Society Park’s bald treetops moving gently in the wind. The rain has stopped temporarily.

Sixten Eriksson. The man Axel Fagelsjo beat up in 1973. The circumstances were described in the file they had received from the archive. Sixten Eriksson had been employed as a farmhand out at Skogsa, and managed to drive one of the tractors into the chapel. Axel Fagelsjo lost his temper and beat him so badly that he was left blind in one eye. He was only given a fine, and had to pay minimal damages to Sixten Eriksson.

Sixten Eriksson is sitting on the blue sofa in front of them with a patch over one eye, his other eye grey-green, almost transparent with cataracts. On the wall behind him hang reproductions of Bruno Liljefors paintings: foxes in the snow, grouse in a forest. The whole room smells of tobacco, and Malin gets the impression that smell is coming from Sixten Eriksson’s pores.

‘It felt like I was inside an egg that was breaking,’ Sixten Eriksson said. ‘I still dream of the pain to this day, I feel it sometimes.’

The nurse who let them in told them Sixten Eriksson was completely blind now that his other eye was afflicted by inoperable cataracts.

Malin looks at him, thinking that there is a directness about him, in spite of his darkness.

‘Of course I was bitter that Axel Fagelsjo didn’t get a harsher punishment, but isn’t that always the way? Those in power aren’t easily dislodged. They took one of my eyes, and fate took the other. That’s all there is to it.’

The court had given Axel Fagelsjo no more than a fine, and showed understanding for his anger: according to the files, Sixten Eriksson had been negligent with the tractor and had caused severe damage to the door of the chapel.

The old man couldn’t have taken revenge on Axel by murdering his son so much later, that much is clear, Malin thinks. But Axel Fagelsjo? He was guilty of extreme brutality then, so could he have done the same to his son?

‘What did you do after that?’ Zeke asks.

‘I worked for NAF, until they shut the factory down.’

‘Did the bitterness pass?’

‘What could I do about it?’

‘The pain?’ Malin said. ‘Did that fade?’

‘No, but you can learn to live with anything.’

Sixten pauses before going on: ‘There’s no pain that you can’t learn to live with. You just have to transfer it onto something else, get it out of yourself.’

Malin feels something change in the room.

The warmth is replaced by a chill, and an inner voice encourages her to ask the next sentence: ‘Your wife. Is she still alive?’

‘We were never married. But we lived together from the age of eighteen. She died of cancer. In her liver.’

‘Did you have any children?’

Before Sixten has a chance to answer, the door opens and a young blonde woman wearing the uniform of an enrolled nurse comes in.

‘Time for your medicine,’ she says, and as the nurse approaches the sofa Sixten answers Malin’s question.

‘A son.’

‘A son?’

‘Yes.’

‘What’s his name?’

The nurse carefully closes the door behind her, and Eriksson smiles, waiting several long seconds before replying: ‘He took his mother’s name. His name’s Sven Evaldsson. He’s lived in Chicago for years now.’

A bus struggles up Djurgardsgatan, and behind the windows pale passengers huddle in their seats, their faces indistinct grimaces through the rain that has once again started to fall.

Malin and Zeke are standing in the rain, both of them thinking.

‘Shouldn’t those farmers have known about Fagelsjo’s conviction? People ought to be talking about it still,’ Zeke says.

‘Even if they knew, perhaps they didn’t realise that we’d want to know,’ Malin says. ‘Or else they didn’t want to talk about it. From their perspective, it’s probably never looked impossible that the Fagelsjo family would get the castle back, in which case it probably makes sense to keep quiet.’

As they’re about to get into the car Malin’s mobile rings.

Unknown number on the display. She answers in the rain.

‘Malin Fors.’

‘This is Jasmin’s mother.’

Jasmin.

Which one of Tove’s friends is that?

Then she remembers the woman in the room of the rehabilitation centre in Soderkoping, beside her daughter’s wheelchair. The sense that her love for her daughter was boundless. If anything like that happened to Tove, could I handle it? The question was back again.

Raindrops on her face, pattering against her coat, the impatient look on Zeke’s face inside the car.

‘Hello. Is there something I can help you with?’

‘I had a dream last night,’ Jasmin Sandsten’s mother says.

Not again, not another dreamer, Malin thinks, seeing Linnea Sjostedt’s face in front of her. We need something concrete now, not more bloody dreams.

‘You had a dream?’

‘I had a dream about a boy with long black hair. I don’t remember his name, but he used to visit Jasmin in the beginning, after the accident. He said they hardly knew each other but he’d been friends with Andreas, the boy who died in the crash. Jasmin’s friends didn’t know anything about him. I remember thinking it was strange that he kept coming, but he was friendly and most of them never came at all. I thought that the sound of people her own age might help her to come back.’

‘And you’ve just had a dream about him?’

Malin doesn’t wait for Jasmin Sandsten’s mother to reply, instead she’s thinking that Anders Dalstrom, the folk singer from the forest, has got long black hair.

So now he’s popped up in the investigation again. In a dream.

‘Long black hair. You don’t remember his name?’

‘No, I’m sorry. But a very well-dressed young man without a face came to me in the dream. He showed me a film of the young man who used to visit Jasmin. A black-and-white film. Jerky and old.

‘Wait a moment. I think his name might have been Anders. His surname was something like Fahlstrom.’

58

Anders Dalstrom takes a sip of his coffee in the branch of Robert’s Coffee attached to the Academic Bookshop, not far from Stadium and Gyllentorget. One of the showy American coffee shops that have successfully seen off the traditional old cafes. Latte hell, Malin thinks.

A lot of people, Saturday. Money burning a hole in their wallets.

The bookshop must do well in this sort of weather, when people are huddled up at home.

‘I’m in the city,’ Anders Dalstrom had said when Malin called: they didn’t want to drive all the way out to the forests outside Bjorsater if he wasn’t home. ‘I’ve come in to get some books. We could meet now if you like.’

And now he’s sitting opposite her and Zeke wearing a blue hooded top and a yellow T-shirt with a green Bruce Springsteen on the chest. He looks tired, has bags under his eyes, and his long black hair looks greasy and unwashed.

You look ten years older than you did out at the cottage, Malin thinks. Is it right to disturb you again? But Malin wants to follow the threads of her conversation with Jasmin’s mother, asking Anders Dalstrom about Jasmin.

‘Why did you visit her? You didn’t really know her, did you?’

‘No. But it used to make me feel better.’

‘Better in what way?’ Zeke asks.

Anders Dalstrom closes his eyes with a sigh.

‘I was working last night. I’m too tired for this.’

‘Better in what way?’ Zeke asks again, sounding firmer this time, and Malin notes that he’s taken her place, asking questions that match her intuition rather than his own, perhaps.

‘I don’t know. It just felt better. It’s so long ago now.’

‘So you didn’t have any sort of relationship with Jasmin?’

‘No. I didn’t know her. Not at all. But I still felt sorry for her. I can hardly remember it now. It was like her silence was my own somehow. I liked the silence.’

‘And you didn’t know that Jerry Petersson was driving the car that New Year’s Eve?’

‘I told you I didn’t last time.’

A bag of books by Anders Dalstrom’s side, a few DVDs.

‘What have you bought?’

‘A new Springsteen biography. A couple of thrillers. Two films of Bob Dylan concerts. And Lord of the Flies.’

‘My daughter loves reading,’ Malin says. ‘But mostly literary novels. Ideally with a bit of romance. But Lord of the Flies is good, the book and the film.’

Anders Dalstrom looks at her, staring into her eyes for a few moments before saying: ‘Speaking of romance: you’ve probably heard it from other people, but there were rumours in high school around the time of the accident that Jerry Petersson was seeing Katarina Fagelsjo.’

I can sniff out an unhappy relationship from a thousand miles away, Malin thinks. And I can pick up the smell of it here, here in Katarina Fagelsjo’s living room, it’s seeping out of this bitter woman’s skin, and you want to tell us, don’t you? You’re the woman in the Anna Ancher painting on the wall, the woman who wants to turn around and tell her story.

‘I’ll go and see her on my own. I might be able to get her to talk.’

Zeke had nodded.

Let her go to see Katarina. It might be dangerous, but probably not. ‘Go. Find out what we need to know.’

White tights. Blue skirt, one leg crossed over the other. High heels, even at home.

Open up. Tell me. You want to, I saw your reaction when I told you what Anders Dalstrom had told us. About the rumours. The romance.

‘You’re mourning Jerry Petersson, aren’t you?’

The perfectly balanced upholstery from Svenskt Tenn behind her back, Josef Frank’s speckled, smiling snakes.

And Katarina’s mask falls. Shatters into a tormented grimace and she starts to cry.

‘Don’t touch me,’ Katarina sobs when Malin makes a move to put her arm around her.

‘Sit down again and I’ll tell you.’

And soon the words are pouring from the puffy, tear-streaked face.

‘I was in love with Jerry Petersson the autumn before the accident. I saw him in the corridors at school, I knew he was off limits for a girl like me, but you should have seen him, Malin, he was ridiculously handsome. Then we ended up at the same party, at the headquarters of the youth wing of the Moderate Party, by mistake, and I don’t remember why but we ended up sitting in the cemetery all night, and then we went down to the river. There used to be an abandoned pump house there, it’s been demolished now.’

Katarina gets up. Goes over to the window facing the river, and with her back to Malin she points, waiting for Malin to join her before she goes on.

‘Over there, on that little island, that’s where the pump house was. It was cold, but I still felt warmer than ever that autumn. Jerry and I used to meet without anyone else knowing. I was head-over-heels in love with him. But Father wouldn’t have wanted anything to do with him. And that was that.’

Then Katarina falls silent, seems to be trying to keep the moment alive, by keeping her memories to herself.

Malin opens her mouth to say something, but Katarina hushes her, giving her a look that tells her to listen, to listen to her, and not to herself.

‘Then he disappeared off to Lund. But he didn’t leave me. I kept an eye on him all those years, through my failed marriage to that idiot Father loved. I never forgot Jerry, I wanted to get back in touch, but I never did, I devoted myself to art instead, buried myself in paintings. Why, why, why did he have to come home again, why did he want the castle? I never understood. If he wanted to get back into my life, surely he could have just called? Don’t you think? He could have just called, couldn’t he?’

You could have called him, Malin thinks.

‘And I should have rung him. Or gone out there. Ditched all my useless lovers. He was there, after all, maybe it was finally time to do something about our wretched, lingering love.’

You always loved him. Like I’ve always loved Janne. Can our love ever end?

‘Did Jerry ever meet your father?’ Malin goes on.

Katarina doesn’t answer. Instead she walks away from the window and out of the room.

Katarina is standing in front of the mirror in the bathroom. Doesn’t recognise her own face.

Then she imagines that someone is holding pictures in front of her eyes, black-and-white pictures that were never taken by a camera but which somehow exist anyway.

Two young people walking beside a river.

A pump house.

Burning wood. And the voice is there, his voice, a voice she has been longing to hear.

‘Do you remember how beautiful you were then, Katarina? That autumn? When we would walk together along the Stangan, taking care that no one saw us, how we would have sex in the old pump house, warmed by the fire we made in an abandoned stove. I would stroke your back, caress it, and we pretended it was summer, and that I was rubbing suncream onto your skin to stop it burning.’

New pictures.

Snow falling. She in her room at the castle. A figure walking through the forest in the cold. The closed doors of the castle.

‘And then, against my will,’ the voice went on, ‘you wanted me to meet your father and mother. So I came out to the castle on the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, like we’d agreed. I took the bus as far as I could, then walked through the cold, through the forest and past fields, until I saw the castle almost forcing the forest aside, on a small rise surrounded by its moat.

‘I walked across the bridge over the moat.

‘Saw the strange green light.

‘And your father opened the door and I looked at him and he realised why I was there, and you came to the door, and he saw something in your eyes, and he shouted that there was no way in hell that someone like me was going to cross his threshold, then he raised his arm and knocked me to the ground with a single blow.

‘He chased me away, over the moat, brandishing an umbrella, and you were shouting that you loved me, I love him, Father, and I ran, I ran and I thought you were going to follow me, but when I turned around at the edge of the forest you were gone, the driveway was empty, the door wasn’t closed, but your mother, Bettina, was standing there, and I thought I could see her smiling.’

Images of herself turning away in the castle doorway. Running up the stairs. Lying on a bed. Standing close to her father. Adjusting her make-up in a mirror.

Shut up, she wants to shout at the voice, shut up, but it goes on: ‘I came to the party. You were there. Fredrik. He had drunk too much, was arrogant towards everyone and everything. It was as if I didn’t exist for you. You didn’t even look at me, and that made me mad. I drank, gulping it down, danced, fumbled with dozens of girls who all wanted me, I made myself unbeatable, I took Jasmin, who was in your class, just because it would upset you, I got behind the wheel of that car just to show the world who made the decisions, and that love really doesn’t matter. I was in charge, and not even love could take that power away.

‘And then, in the field, in the snow and the blood and the silence, I looked at Jonas Karlsson, begged him to say he was the one driving, promised him the world.

‘And do you know, he did what I said, I got him to do it, and I realised deep down at that moment that I could have almost anything I wanted in this world, as long as I was ruthless enough. That I could make the lawnmower blades shut up.

‘But not you, Katarina. I could never have you. Not the person you are.

‘So, sure, in a way I was both born and died on that New Year’s Eve.’

Images of a car wreck. Funerals, a wheelchair with a mute body, a man with his back to her in an office chair, a steady stream of images from a life she had never known.

‘And when I bought Skogsa, I wanted to breathe life into what had died,’ the voice goes on.

‘That was the very worst vanity, worse than any alchemist’s.

‘Soon I was standing in the very same doorway that I had been refused entry to for all those years. I walked bare-chested through the rooms, feeling the cold, rough surface of the stone against my skin.’

The images are gone. All that is left is the mirror, her eyes, the tears she knows are there inside them somewhere.

59

Linkoping, March and onwards

Jerry rubs against the walls of a room illuminated by the one hundred and three candles in the chandelier suspended five metres above his head. The stones are irregular and rough against his chest and back, like the surface of some as yet unexplored hostile planet.

The painting of the man and woman with the suncream is hanging in front of him.

The rooms of the castle. One after the other.

The telephones. She’s only a phone call away. He sits beneath his paintings and chants the number like a mantra.

It never occurs to him that she might be angry about what he has done, that she might think he has torn her family’s history from their hands.

But he never dials her number. Instead he throws himself into the practical business that comes with a property like this, sorting out the tenant farmers, and labourers of all different trades, visiting the whores he finds on the Internet, even in Linkoping, often middle-aged women with an unnaturally high sex-drive who may as well make a bit of money from satisfying their lust. He considers calling the young solicitor he bedded when the contracts were signed, but thinks that things might get a bit too close to home if he did that.

Some evenings and mornings he heads out into the estate. Drives through the black landscape, past houses and trees and fields, the field that seems to encompass the three beings that he is: past, present, and whatever is to come tomorrow.

He imagines he can see green light streaming from the moat and has green lanterns installed along it, as a response to the optical phenomenon down in the water.

He stands on the other side of the door, resting inside himself, waiting for a call, for a car he wants to come and pull up in front of the castle, but which never arrives. He stands still, takes detours around the love he can never bring himself to open up to for a second time. That is the fear he can never conquer.

Instead he receives a letter through the post. Handwritten.

He reads the letter at the kitchen table, early one morning that autumn, when the skies have opened and seem to be raining corrosive acid onto the world of men.

He folds the letter, thinking that he needs to deal with this, cauterise it once and for all.

60

Saturday, 1, Sunday, 2 November

Push the bar up.

You’re alone in the gym, Malin, if you can’t manage it the bar will crush your throat and that’ll be an end to all your problems.

To all your breathing. To all love.

Seventy kilos on the bar, more than her own weight, and she pushes it up another ten times before letting it slip back into the supporting frame.

Janne. Now he’s telling me what I can and can’t do.

To hell with that.

But maybe he’s right.

Tove. I want to say I’m sorry. But you’re right to leave me alone for a while, aren’t you?

How could I?

Her body wet with sweat. As if she’s been running through the rain she can see through the little windows along the ceiling.

They’ve put up new wallpaper in the room. In place of the old vomit-green, there is now an even worse pink wallpaper with little purple flowers.

This is a gym, Malin thinks. Not a fucking girl’s bedroom.

She lies down on the bench again.

Ten more reps and she feels her muscles working, the effort suppressing every thought of drink. Rehab. Bollocks. I don’t need that.

Every time she lifts the bar towards the blinding-white ceiling, she tries to get closer to the core of the investigation.

Lactic acid is burning through her body and she gets up, boxing the air, shaking life into mute, oxygen-starved tissue, and says as she punches: ‘I. Am. Missing. Something. But. What?’

In the sauna, after first a long cold shower, then a hot one, she reads Daniel Hogfeldt’s latest article about the murders, the pages of the Correspondent hot on her fingers.

He goes through the connections between the murders and says that sources within the police are convinced they are linked, but that they don’t know for sure yet.

In a separate article he gives a well-informed account of Fredrik Fagelsjo’s failed financial investments, and how the family came to lose Skogsa. He concludes: ‘Suspicion may now be focused on the Fagelsjo family, who some people claim would do anything to get the estate back.’

He doesn’t mention the family’s new money, the inheritance they’ve received. But there are pictures of the houses they currently live in. Probably new photographs. The vultures never leave the bereaved in peace.

Then a picture of Linnea Sjostedt by her cottage tucked away near Skogsa. Daniel reports her as saying: ‘Of course they might have wanted revenge on Fredrik for losing the estate. It means everything to them.’

Ninety degrees in here.

Ten minutes and her body is shrieking, the sweat streaming from every pore, but Malin is enjoying the pain.

Nor has Daniel found out about Axel Fagelsjo’s old conviction for actual bodily harm. Nor that Jerry Petersson was driving the car on that fateful New Year’s Eve. That’s good, maybe there are fewer leaks in the police station now. And Daniel is a decent person, really. He’s never pressed her for information when she’s been drunk, never tried to turn her into one of the leaks.

Malin stands naked in the changing room.

One message on her phone.

Daniel Hogfeldt’s number, by coincidence, and she assumes that he must want a session that evening. She calls the messaging service to hear what he had to say.

‘Daniel here. I was just going to say that I’ve had an anonymous tip-off about your investigation. Call me?’

Daniel.

He doesn’t usually give us anything. Keeps any tips he receives for himself. And these days people keen for money and media attention often call the papers with tip-offs and leads instead of calling us.

How did that happen?

‘Daniel.’

‘It’s me. I got your message.’

‘Yes, I just wanted to say that I got a tip-off about Fagelsjo over the phone. That it had to be the father and daughter who killed Fredrik. As revenge. That they’re responsible.’

‘I can’t deny that we’ve considered that.’

‘Of course, Malin. But this informant was particularly insistent. He sounded relieved when I said I was already thinking of writing about the connection.’

‘A nutter?’

‘No, but there was something about him. Something that didn’t fit.’

‘What was his name? Did you get his number?’

‘No, no number came up. No name. And that’s pretty unusual as well.’

He’s using this as an excuse to call me, Malin thinks.

He’s got nothing. They get loads of tip-offs.

Anonymous.

About all sorts of things.

‘I know what you’re thinking, Malin. But this one was different. The fact that he was so insistent scared me.’

‘Did he have anything new to say?’

‘No.’

‘OK,’ Malin says. ‘You can come around to mine at nine o’clock tonight, then you can have what you want.’

Daniel is silent.

Malin sees herself in the changing-room mirror, careful not to look at her tired face, looks instead at her toned body.

‘You really are something, Fors, aren’t you? I was thinking I could actually help you with your work for once.’

‘What, with that?’

‘With the fact that it was a man and not a woman who called, for instance.’

‘Are you coming?’

The line breaks and goes silent.

He’s coming.

Tell me you’re coming. Then everything will be all right, if only for half an hour or so. That’s enough.

Malin is lying on her bed in her dressing gown, waiting for Daniel to come, feeling the urge to have him inside her.

Nine o’clock comes.

Half past.

Ten o’clock. And she feels like calling him, but knows that such humiliation would be pointless, that he actually didn’t want her and really was only trying to help.

In his own awkward way, with a meaningless tip-off.

Someone who wants things to be a particular way. Who wants to direct them to look in one direction when they ought to be looking elsewhere. The thought pops up again.

On the way home from the gym she called her dad.

He evidently hadn’t noticed any Spanish police watching over him and Mum, but on the other hand he hadn’t noticed his picture being taken either.

He told her that he and her mother were thinking of coming home for Christmas. Malin replied that Tove would be happy, but that they should expect fairly strained family relationships.

‘Are you having a tough time?’ Dad asked.

‘No, there’s just an awful lot of autumn at the moment,’ she said, thinking: Dad, we’re fighting for our lives on my planet.

Are you Malin? Fighting for your life?

I think my father’s doing the same on his planet.

Axel Fagelsjo.

Father.

I can see both you and him clearly, you’re lying in your bed, and you’ve fallen asleep and are sleeping a dreamless sleep, a well-deserved rest after all that work trying to keep your impulses under control.

Axel is sitting at his kitchen table on Drottninggatan. He’s taken his beloved shotgun out of the gun cabinet in the bedroom.

He smells the gun, I’ve seen him do that before, and I don’t know why he does it. Now he’s locking the gun away in the cabinet again.

I don’t actually know what happened to me, Malin. I don’t remember anything. That seems to be unusual, from what I’ve been able to gather from talking to other people up here where I am.

But that doesn’t matter.

Because I’ve got you.

You’ll be able to tell me what my fate was.

You talk of your fate, Fredrik, but what do you know, my silver-spoon boy, about fate?

There’s no such thing as fate, just events that are the result of conscious actions.

When I ended up in the moat it was my own fault, no one else’s.

In the most fundamental sense, I caused that event myself.

You imagine, Malin, that you’re going to give me some sort of justice, reparation after death. As if I could have any use for that?

I don’t need anything from any of you.

I am already everything.

On Sunday a hard rain is lashing the ground, the people.

Malin stands in the window of her flat looking at the church tower, the way even the crows seem to be suffering in this wind.

She wants to hear Tove’s voice, meet her, they could have spent the whole day together now that Sven has forced her to take the day off.

But she doesn’t call her daughter, she does what Janne said, or at least what she thought he meant. She keeps her distance. Avoids her own reflection. If she were fourteen years old, she’d be slashing her wrists.

Instead she puts on her jogging clothes and runs twenty kilometres on various routes through Linkoping. She sweats under the tight fabric, the city disappears before her eyes and she feels her heart, feels that she can still trust its power.

Back home again, she calls the station. Waldemar Ekenberg tells her that nothing new has happened in the case.

She leafs through her papers about Maria Murvall. She prepares her talk at the kitchen table. The evening darkness settles outside the window.

Malin looks around the kitchen, thinking: I have nothing, I can’t even handle Tove. And will I ever get the chance again?