Текст книги "The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two"

Автор книги: John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

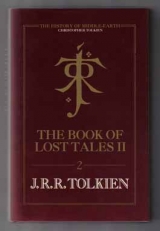

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Book of Lost Tales

Part II

Christopher Tolkien

PREFACE

This second part of The Book of Lost Tales is arranged on the same lines and with the same intentions as the first part, as described in the Foreword to it, pages 10–11. References to the first part are given in the form ‘I. 240’, to the second as ‘p. 240’, except where a reference is made to both, e.g. ‘I. 222, II. 292’.

As before, I have adopted a consistent (if not necessarily ‘correct’) system of accentuation for names; and in the cases of Mim and Niniel, written thus throughout, I give Mоm and Nнniel.

The two pages from the original manuscripts are reproduced with the permission of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and I wish to express my thanks to the staff of the Department of Western Manuscripts at the Bodleian for their assistance. The correspondence of the original pages to the printed text in this book is as follows:

(1) The page from the manuscript of The Tale of Tinъviel. Upper part: printed text page 24 (7 lines up, the sorest dread) to page 25 (line 3, so swiftly.”). Lower part: printed text page 25 (11 lines up, the harsh voice) to page 26 (line 7, but Tevildo).

(2) The page from the manuscript of The Fall of Gondolin. Upper part: printed text page 189 (line 12, “Now,” therefore said Galdor to line 20 if no further.”). Lower part: printed text page 189 (line 27, But the others, led by one Legolas Greenleaf) to page 190 (line 11, leaving the main company to follow he).

For differences in the printed text of The Fall of Gondolin from the page reproduced see page 201, notes 34–36, and page 203, Bad Uthwen; some other small differences not referred to in the notes are also due to later changes made to the text B of the Tale (see pages 146–7).

These pages illustrate the complicated ‘jigsaw’ of the manuscripts of the Lost Tales described in the Foreword to Part I, page 10.

The third volume in this ‘History’ will contain the alliterative Lay of the Children of Hъrin (c. 1918–1925) and the Lay of Leithian (1925–1931), together with the commentary on a part of the latter by C. S. Lewis, and the rewriting of the poem that my father embarked on after the completion of The Lord of the Rings.

I THE TALE OF TINЪVIEL

The Tale of Tinъviel was written in 1917, but the earliest extant text is later, being a manuscript in ink over an erased original in pencil; and in fact my father’s rewriting of this tale seems to have been one of the last completed elements in the Lost Tales (see I. 203–4).

There is also a typescript version of the Tale of Tinъviel, later than the manuscript but belonging to the same ‘phase’ of the mythology: my father had the manuscript before him and changed the text as he went along. Significant differences between the two versions of the tale are given on pp. 41 ff.

In the manuscript the tale is headed: ‘Link to the Tale of Tinъviel, also the Tale of Tinъviel.’ The Link begins with the following passage:

‘Great was the power of Melko for ill,’ said Eriol, ‘if he could indeed destroy with his cunning the happiness and glory of the Gods and Elves, darkening the light of their dwelling and bringing all their love to naught. This must surely be the worst deed that ever he has done.’

‘Of a truth never has such evil again been done in Valinor,’ said Lindo, ‘but Melko’s hand has laboured at worse things in the world, and the seeds of his evil have waxen since to a great and terrible growth.’

‘Nay,’ said Eriol, ‘yet can my heart not think of other griefs, for sorrow at the destruction of those most fair Trees and the darkness of the world.’

This passage was struck out, and is not found in the typescript text, but it reappears in almost identical form at the end of The Flight of the Noldoli (I. 169). The reason for this was that my father decided that the Tale of the Sun and Moon, rather than Tinъviel, should follow The Darkening of Valinor and The Flight of the Noldoli (see I. 203–4, where the complex question of the re-ordering of the Tales at this point is discussed). The opening words of the next part of the Link, ‘Now in the days soon after the telling of this tale’, referred, when they were written, to the tale of The Darkening of Valinor and The Flight of the Noldoli; but it is never made plain to what tale they were to refer when Tinъviel had been removed from its earlier position.

The two versions of the Link are at first very close, but when Eriol speaks of his own past history they diverge. For the earlier part I give the typescript text alone, and when they diverge I give them both in succession. All discussion of this story of Eriol’s life is postponed to Chapter VI.

Now in the days soon after the telling of this tale, behold, winter approached the land of Tol Eressлa, for now had Eriol forgetful of his wandering mood abode some time in old Kortirion. Never in those months did he fare beyond the good tilth that lay without the grey walls of that town, but many a hall of the kindreds of the Inwir and the Teleri received him as their glad guest, and ever more skilled in the tongues of the Elves did he become, and more deep in knowledge of their customs, of their tales and songs.

Then was winter come sudden upon the Lonely Isle, and the lawns and gardens drew on a sparkling mantle of white snows; their fountains were still, and all their bare trees silent, and the far sun glinted pale amid the mist or splintered upon facets of long hanging ice. Still fared Eriol not away, but watched the cold moon from the frosty skies look down upon Mar Vanwa Tyaliйva, and when above the roofs the stars gleamed blue he would listen, yet no sound of the flutes of Timpinen heard he now; for the breath of summer is that sprite, and or ever autumn’s secret presence fills the air he takes his grey magic boat, and the swallows draw him far away.

Even so Eriol knew laughter and merriment and musics too, and song, in the dwellings of Kortirion—even Eriol the wanderer whose heart before had known no rest. Came now a grey day, and a wan afternoon, but within was firelight and good warmth and dancing and merry children’s noise, for Eriol was making a great play with the maids and boys in the Hall of Play Regained. There at length tired with their mirth they cast themselves down upon the rugs before the hearth, and a child among them, a little maid, said: ‘Tell me, O Eriol, a tale!’

‘What then shall I tell, O Vлannл?’ said he, and she, clambering upon his knee, said: ‘A tale of Men and of children in the Great Lands, or of thy home—and didst thou have a garden there such as we, where poppies grew and pansies like those that grow in my corner by the Arbour of the Thrushes?’

I give now the manuscript version of the remainder of the Link passage:

Then Eriol told her of his home that was in an old town of Men girt with a wall now crumbled and broken, and a river ran thereby over which a castle with a great tower hung. ‘A very high tower indeed,’ said he, ‘and the moon climbed high or ever he thrust his face above it.’ ‘Was it then as high as Ingil’s Tirin?’ said Vлannл, but Eriol said that that he could not guess, for ’twas very many years agone since he had seen that castle or its tower, for ‘O Vлannл,’ said he, ‘I lived there but a while, and not after I was grown to be a boy. My father came of a coastward folk, and the love of the sea that I had never seen was in my bones, and my father whetted my desire, for he told me tales that his father had told him before. Now my mother died in a cruel and hungry siege of that old town, and my father was slain in bitter fight about the walls, and in the end I Eriol escaped to the shoreland of the Western Sea, and mostly have lived upon the bosom of the waves or by its side since those far days.’

Now the children about were filled with sadness at the sorrows that fell on those dwellers in the Great Lands, and at the wars and death, and Vлannл clung to Eriol, saying: ‘O Melinon, go never to a war—or hast thou ever yet?’

‘Aye, often enough,’ said Eriol, ‘but not to the great wars of the earthly kings and mighty nations which are cruel and bitter, and many fair lands and lovely things and even women and sweet maids such as thou Vлannл Melinir are whelmed by them in ruin; yet gallant affrays have I seen wherein small bands of brave men do sometimes meet and swift blows are dealt. But behold, why speak we of these things, little one; wouldst not hear rather of my first ventures on the sea?’

Then was there much eagerness alight, and Eriol told them of his wanderings about the western havens, of the comrades he made and the ports he knew, of how he was wrecked upon far western islands until at last upon one lonely one he came on an ancient sailor who gave him shelter, and over a fire within his lonely cabin told him strange tales of things beyond the Western Seas, of the Magic Isles and that most lonely one that lay beyond. Long ago had he once sighted it shining afar off, and after had he sought it many a day in vain.

‘Ever after,’ said Eriol, ‘did I sail more curiously about the western isles seeking more stories of the kind, and thus it is indeed that after many great voyages I came myself by the blessing of the Gods to Tol Eressлa in the end—wherefore I now sit here talking to thee, Vлannл, till my words have run dry.’

Then nonetheless did a boy, Ausir, beg him to tell more of ships and the sea, but Eriol said: ‘Nay—still is there time ere Ilfiniol ring the gong for evening meat: come, one of you children, tell me a tale that you have heard!’ Then Vлannл sat up and clapped her hands, saying: ‘I will tell you the Tale of Tinъviel.’

The typescript version of this passage reads as follows:

Then Eriol told of his home of long ago, that was in an ancient town of Men girt with a wall now crumbled and broken, for the folk that dwelt there had long known days of rich and easy peace. A river ran thereby, o’er which a castle with a great tower hung. ‘There dwelt a mighty duke,’ said he, ‘and did he gaze from the topmost battlements never might he see the bounds of his wide domain, save where far to east the blue shapes of the great mountains lay—yet was that tower held the most lofty that stood in the lands of Men.’ ‘Was it as high as great Ingil’s Tirin?’ said Vлannл, but said Eriol: ‘A very high tower indeed was it, and the moon climbed far or ever he thrust his face above it, yet may I not now guess how high, O Vлannл, for ’tis many years agone since last I saw that castle or its steep tower. War fell suddenly on that town amid its slumbrous peace, nor were its crumbled walls able to withstand the onslaught of the wild men from the Mountains of the East. There perished my mother in that cruel and hungry siege, and my father was slain fighting bitterly about the walls in the last sack. In those far days was I not yet war-high, and a bondslave was I made.

‘Know then that my father was come of a coastward folk ere he wandered to that place, and the longing for the sea that I had never seen was in my bones; which often had my father whetted, telling me tales of the wide waters and recalling lore that he had learned of his father aforetime. Small need to tell of my travail thereafter in thraldom, for in the end I brake my bonds and got me to the shoreland of the Western Sea—and mostly have I lived upon the bosom of its waves or by its side since those old days.’

Now hearing of the sorrows that fell upon the dwellers in the Great Lands, the wars and death, the children were filled with sadness, and Vлannл clung to Eriol, saying: ‘O Melinon, go thou never to a war—or hast thou ever yet?’

‘Aye, often enough,’ said Eriol, ‘yet not to the great wars of the earthly kings and mighty nations, which are cruel and bitter, whelming in their ruin all the beauty both of the earth and of those fair things that men fashion with their hands in times of peace—nay, they spare not sweet women and tender maids, such as thou, Vлannл Melinir, for then are men drunk with wrath and the lust of blood, and Melko fares abroad. But gallant affrays have I seen wherein brave men did sometimes meet, and swift blows were dealt, and strength of body and of heart was proven—but, behold, why speak we of these things, little one? Wouldst not hear rather of my ventures on the sea?’

Then was there much eagerness alight, and Eriol told them of his first wanderings about the western havens, of the comrades he made, and the ports he knew; of how he was one time wrecked upon far western islands and there upon a lonely eyot found an ancient mariner who dwelt for ever solitary in a cabin on the shore, that he had fashioned of the timbers of his boat. ‘More wise was he,’ said Eriol, ‘in all matters of the sea than any other I have met, and much of wizardry was there in his lore. Strange things he told me of regions far beyond the Western Sea, of the Magic Isles and that most lonely one that lies behind. Once long ago, he said, he had sighted it glimmering afar off, and after had he sought it many a day in vain. Much lore he taught me of the hidden seas, and the dark and trackless waters, and without this never had I found this sweetest land, or this dear town or the Cottage of Lost Play—yet it was not without long and grievous search thereafter, and many a weary voyage, that I came myself by the blessing of the Gods to Tol Eressлa at the last—wherefore I now sit here talking to thee, Vлannл, till my words have run dry.’

Then nevertheless did a boy, Ausir, beg him to tell more of ships and the sea, saying: ‘For knowest thou not, O Eriol, that that ancient mariner beside the lonely sea was none other than Ulmo’s self, who appeareth not seldom thus to those voyagers whom he loves—yet he who has spoken with Ulmo must have many a tale to tell that will not be stale in the ears even of those that dwell here in Kortirion.’ But Eriol at that time believed not that saying of Ausir’s, and said: ‘Nay, pay me your debt ere Ilfrin ring the gong for evening meat—come, one of you shall tell me a tale that you have heard.’

Then did Vлannл sit up and clap her hands, crying: ‘I will tell thee the Tale of Tinъviel.’

The Tale of Tinъviel

I give now the text of the Tale of Tinъviel as it appears in the manuscript. The Link is not in fact distinguished or separated in any way from the tale proper, and Vлannл makes no formal opening to it.

‘Who was then Tinъviel?’ said Eriol. ‘Know you not?’ said Ausir; ‘Tinъviel was the daughter of Tinwл Linto.’ ‘Tinwelint’, said Vлannл, but said the other: ‘’Tis all one, but the Elves of this house who love the tale do say Tinwл Linto, though Vairл hath said that Tinwл alone is his right name ere he wandered in the woods.’

‘Hush thee, Ausir,’ said Vлannл, ‘for it is my tale and I will tell it to Eriol. Did I not see Gwendeling and Tinъviel once with my own eyes when journeying by the Way of Dreams in long past days?’1

‘What was Queen Wendelin like (for so do the Elves call her),2 O Vлannл, if thou sawest her?’ said Ausir.

‘Slender and very dark of hair,’ said Vлannл, ‘and her skin was white and pale, but her eyes shone and seemed deep, and she was clad in filmy garments most lovely yet of black, jet-spangled and girt with silver. If ever she sang, or if she danced, dreams and slumbers passed over your head and made it heavy. Indeed she was a sprite that escaped from Lуrien’s gardens before even Kфr was built, and she wandered in the wooded places of the world, and nightingales went with her and often sang about her. It was the song of these birds that smote the ears of Tinwelint, leader of that tribe of the Eldar that after were the Solosimpi the pipers of the shore, as he fared with his companions behind the horse of Oromл from Palisor. Ilъvatar had set a seed of music in the hearts of all that kindred, or so Vairл saith, and she is of them, and it blossomed after very wondrously, but now the song of Gwendeling’s nightingales was the most beautiful music that Tinwelint had ever heard, and he strayed aside for a moment, as he thought, from the host, seeking in the dark trees whence it might come.

And it is said that it was not a moment he hearkened, but many years, and vainly his people sought him, until at length they followed Oromл and were borne upon Tol Eressлa far away, and he saw them never again. Yet after a while as it seemed to him he came upon Gwendeling lying in a bed of leaves gazing at the stars above her and hearkening also to her birds. Now Tinwelint stepping softly stooped and looked upon her, thinking “Lo, here is a fairer being even than the most beautiful of my own folk”—for indeed Gwendeling was not elf or woman but of the children of the Gods; and bending further to touch a tress of her hair he snapped a twig with his foot. Then Gwendeling was up and away laughing softly, sometimes singing distantly or dancing ever just before him, till a swoon of fragrant slumbers fell upon him and he fell face downward neath the trees and slept a very great while.

Now when he awoke he thought no more of his people (and indeed it had been vain, for long now had those reached Valinor) but desired only to see the twilight-lady; but she was not far, for she had remained nigh at hand and watched over him. More of their story I know not, O Eriol, save that in the end she became his wife, for Tinwelint and Gwendeling very long indeed were king and queen of the Lost Elves of Artanor or the Land Beyond, or so it is said here.

Long, long after, as thou knowest, Melko brake again into the world from Valinor, and all the Eldar both those who remained in the dark or had been lost upon the march from Palisor and those Noldoli too who fared back into the world after him seeking their stolen treasury fell beneath his power as thralls. Yet it is told that many there were who escaped and wandered in the woods and empty places, and of these many a wild and woodland clan rallied beneath King Tinwelint. Of those the most were Ilkorindi—which is to say Eldar that never had beheld Valinor or the Two Trees or dwelt in Kфr—and eerie they were and strange beings, knowing little of light or loveliness or of musics save it be dark songs and chantings of a rugged wonder that faded in the wooded places or echoed in deep caves. Different indeed did they become when the Sun arose, and indeed before that already were their numbers mingled with a many wandering Gnomes, and wayward sprites too there were of Lуrien’s host that dwelt in the courts of Tinwelint, being followers of Gwendeling, and these were not of the kindreds of the Eldaliл.

Now in the days of Sunlight and Moonsheen still dwelt Tinwelint in Artanor, and nor he nor the most of his folk went to the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, though that story toucheth not this tale. Yet was his lordship greatly increased after that unhappy field by fugitives that fled to his protection. Hidden was his dwelling from the vision and knowledge of Melko by the magics of Gwendeling the fay, and she wove spells about the paths thereto that none but the Eldar might tread them easily, and so was the king secured from all dangers save it be treachery alone. Now his halls were builded in a deep cavern of great size, and they were nonetheless a kingly and a fair abode. This cavern was in the heart of the mighty forest of Artanor that is the mightiest of forests, and a stream ran before its doors, but none could enter that portal save across the stream, and a bridge spanned it narrow and well-guarded. Those places were not ill albeit the Iron Mountains were not utterly distant beyond whom lay Hisilуmл where dwelt Men, and thrall-Noldoli laboured, and few free-Eldar went.

Lo, now I will tell you of things that happened in the halls of Tinwelint after the arising of the Sun indeed but long ere the unforgotten Battle of Unnumbered Tears. And Melko had not completed his designs nor had he unveiled his full might and cruelty.

Two children had Tinwelint then, Dairon and Tinъviel, and Tinъviel was a maiden, and the most beautiful of all the maidens of the hidden Elves, and indeed few have been so fair, for her mother was a fay, a daughter of the Gods; but Dairon was then a boy strong and merry, and above all things he delighted to play upon a pipe of reeds or other woodland instruments, and he is named now among the three most magic players of the Elves, and the others are Tinfang Warble and Ivбrл who plays beside the sea. But Tinъviel’s joy was rather in the dance, and no names are set with hers for the beauty and subtlety of her twinkling feet.

Now it was the delight of Dairon and Tinъviel to fare away from the cavernous palace of Tinwelint their father and together spend long times amid the trees. There often would Dairon sit upon a tussock or a tree-root and make music while Tinъviel danced thereto, and when she danced to the playing of Dairon more lissom was she than Gwendeling, more magical than Tinfang Warble neath the moon, nor may any see such lilting save be it only in the rose gardens of Valinor where Nessa dances on the lawns of never-fading green.

Even at night when the moon shone pale still would they play and dance, and they were not afraid as I should be, for the rule of Tinwelint and of Gwendeling held evil from the woods and Melko troubled them not as yet, and Men were hemmed beyond the hills.

Now the place that they loved the most was a shady spot, and elms grew there, and beech too, but these were not very tall, and some chestnut trees there were with white flowers, but the ground was moist and a great misty growth of hemlocks rose beneath the trees. On a time of June they were playing there, and the white umbels of the hemlocks were like a cloud about the boles of the trees, and there Tinъviel danced until the evening faded late, and there were many white moths abroad. Tinъviel being a fairy minded them not as many of the children of Men do, although she loved not beetles, and spiders will none of the Eldar touch because of Ungweliantл—but now the white moths flittered about her head and Dairon trilled an eerie tune, when suddenly that strange thing befell.

Never have I heard how Beren came thither over the hills; yet was he braver than most, as thou shalt hear, and ’twas the love of wandering maybe alone that had sped him through the terrors of the Iron Mountains until he reached the Lands Beyond.

Now Beren was a Gnome, son of Egnor the forester who hunted in the darker places3 in the north of Hisilуmл. Dread and suspicion was between the Eldar and those of their kindred that had tasted the slavery of Melko, and in this did the evil deeds of the Gnomes at the Haven of the Swans revenge itself. Now the lies of Melko ran among Beren’s folk so that they believed evil things of the secret Elves, yet now did he see Tinъviel dancing in the twilight, and Tinъviel was in a silver-pearly dress, and her bare white feet were twinkling among the hemlock-stems. Then Beren cared not whether she were Vala or Elf or child of Men and crept near to see; and he leant against a young elm that grew upon a mound so that he might look down into the little glade where she was dancing, for the enchantment made him faint. So slender was she and so fair that at length he stood heedlessly in the open the better to gaze upon her, and at that moment the full moon came brightly through the boughs and Dairon caught sight of Beren’s face. Straightway did he perceive that he was none of their folk, and all the Elves of the woodland thought of the Gnomes of Dor Lуmin as treacherous creatures, cruel and faithless, wherefore Dairon dropped his instrument and crying “Flee, flee, O Tinъviel, an enemy walks this wood” he was gone swiftly through the trees. Then Tinъviel in her amaze followed not straightway, for she understood not his words at once, and knowing she could not run or leap so hardily as her brother she slipped suddenly down among the white hemlocks and hid herself beneath a very tall flower with many spreading leaves; and here she looked in her white raiment like a spatter of moonlight shimmering through the leaves upon the floor.

Then Beren was sad, for he was lonely and was grieved at their fright, and he looked for Tinъviel everywhere about, thinking her not fled. Thus suddenly did he lay his hand upon her slender arm beneath the leaves, and with a cry she started away from him and flitted as fast as she could in the wan light, in and about the tree-trunks and the hemlock-stalks. The tender touch of her arm made Beren yet more eager than before to find her, and he followed swiftly and yet not swiftly enough, for in the end she escaped him, and reached the dwellings of her father in fear; nor did she dance alone in the woods for many a day after.

This was a great sorrow to Beren, who would not leave those places, hoping to see that fair elfin maiden dance yet again, and he wandered in the wood growing wild and lonely for many a day and searching for Tinъviel. By dawn and dusk he sought her, but ever more hopefully when the moon shone bright. At last one night he caught a sparkle afar off, and lo, there she was dancing alone on a little treeless knoll and Dairon was not there. Often and often she came there after and danced and sang to herself, and sometimes Dairon would be nigh, and then Beren watched from the wood’s edge afar, and sometimes he was away and Beren crept then closer. Indeed for long Tinъviel knew of his coming and feigned otherwise, and for long her fear had departed by reason of the wistful hunger of his face lit by the moonlight; and she saw that he was kind and in love with her beautiful dancing.

Then Beren took to following Tinъviel secretly through the woods even to the entrance of the cave and the bridge’s head, and when she was gone in he would cry across the stream, softly saying “Tinъviel”, for he had caught the name from Dairon’s lips; and although he knew it not Tinъviel often hearkened from within the shadows of the cavernous doors and laughed softly or smiled. At length one day as she danced alone he stepped out more boldly and said to her: “Tinъviel, teach me to dance.” “Who art thou?” said she. “Beren. I am from across the Bitter Hills.” “Then if thou wouldst dance, follow me,” said the maiden, and she danced before Beren away, and away into the woods, nimbly and yet not so fast that he could not follow, and ever and anon she would look back and laugh at him stumbling after, saying “Dance, Beren, dance! as they dance beyond the Bitter Hills!” In this way they came by winding paths to the abode of Tinwelint, and Tinъviel beckoned Beren beyond the stream, and he followed her wondering down into the cave and the deep halls of her home.

When however Beren found himself before the king he was abashed, and of the stateliness of Queen Gwendeling he was in great awe, and behold when the king said: “Who art thou that stumbleth into my halls unbidden?” he had nought to say. Tinъviel answered therefore for him, saying: “This, my father, is Beren, a wanderer from beyond the hills, and he would learn to dance as the Elves of Artanor can dance,” and she laughed, but the king frowned when he heard whence Beren came, and he said: “Put away thy light words, my child, and say has this wild Elf of the shadows sought to do thee any harm?”

“Nay, father,” said she, “and I think there is not evil in his heart at all, and be thou not harsh with him, unless thou desirest to see thy daughter Tinъviel weep, for more wonder has he at my dancing than any that I have known.” Therefore said Tinwelint now: “O Beren son of the Noldoli, what dost thou desire of the Elves of the wood ere thou returnest whence thou camest?”

So great was the amazed joy of Beren’s heart when Tinъviel spake thus for him to her father that his courage rose within him, and his adventurous spirit that had brought him out of Hisilуmл and over the Mountains of Iron awoke again, and looking boldly upon Tinwelint he said: “Why, O king, I desire thy daughter Tinъviel, for she is the fairest and most sweet of all maidens I have seen or dreamed of.”

Then was there a silence in the hall, save that Dairon laughed, and all who heard were astounded, but Tinъviel cast down her eyes, and the king glancing at the wild and rugged aspect of Beren burst also into laughter, whereat Beren flushed for shame, and Tinъviel’s heart was sore for him. “Why! wed my Tinъviel fairest of the maidens of the world, and become a prince of the woodland Elves—’tis but a little boon for a stranger to ask,” quoth Tinwelint. “Haply I may with right ask somewhat in return. Nothing great shall it be, a token only of thy esteem. Bring me a Silmaril from the Crown of Melko, and that day Tinъviel weds thee, an she will.”

Then all in that place knew that the king treated the matter as an uncouth jest, having pity on the Gnome, and they smiled, for the fame of the Silmarils of Fлanor was now great throughout the world, and the Noldoli had told tales of them, and many that had escaped from Angamandi had seen them now blazing lustrous in the iron crown of Melko. Never did this crown leave his head, and he treasured those jewels as his eyes, and no one in the world, or fay or elf or man, could hope ever to set finger even on them and live. This indeed did Beren know, and he guessed the meaning of their mocking smiles, and aflame with anger he cried: “Nay, but ’tis too small a gift to the father of so sweet a bride. Strange nonetheless seem to me the customs of the woodland Elves, like to the rude laws of the folk of Men, that thou shouldst name the gift unoffered, yet lo! I Beren, a huntsman of the Noldoli,4 will fulfil thy small desire,” and with that he burst from the hall while all stood astonished; but Tinъviel wept suddenly. “’Twas ill done, O my father,” she cried, “to send one to his death with thy sorry jesting—for now methinks he will attempt the deed, being maddened by thy scorn, and Melko will slay him, and none will look ever again with such love upon my dancing.”

Then said the king: “’Twill not be the first of Gnomes that Melko has slain and for less reason. It is well for him that he lies not bound here in grievous spells for his trespass in my halls and for his insolent speech” yet Gwendeling said nought, neither did she chide Tinъviel or question her sudden weeping for this unknown wanderer.