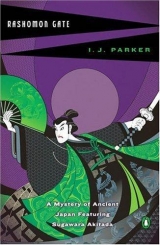

Текст книги "Rashomon Gate "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Nine

Tear-Drenched Sleeves

The next day was also a holiday because it was the day when the Kamo virgin returned from the shrine to her palace. Akitada called on his mother, as he did most mornings. He found her at breakfast with his sisters and asked how they had enjoyed their outing the previous day.

"Tamako is a most charming person," cried his younger sister Yoshiko. Remembering her brother's ill-fated courtship, she blushed a little and added, "She stayed quite late with us and promised to return soon. We were delighted to have her company."

Akitada's heart sank. He had no wish to face any more embarrassing encounters with Tamako. "I am glad you had a pleasant day," he said and glanced at his mother.

"It appears the young woman gardens," Lady Sugawara informed him. "She had a number of helpful suggestions for us. As you can see," she waved a careless hand towards the lush growth surrounding her new terrace, "this place is overgrown like an abandoned ruin. It is too bad that I must rely on chance encounters to get things done."

"I thought you liked the garden this way," said Akitada, hurt in spite of the fact that he knew his mother was still angry with him for other reasons. "All you have to do is ask, and I will have Tora see to some trimming and replanting."

"Hmph! That fellow is gone more than he is here," grumbled his mother.

"Last night he did not come home at all," volunteered his sister Akiko.

Akitada's mother cast her eyes to heaven and sighed deeply. "No doubt he is in jail at this very moment," she said. "To think what I have come to. A dilapidated home and a bandit for a servant! This was once a great house, bustling with well-trained servants. Now we exist like exiles condemned to the wilderness of a distant province."

"I am sorry you are so downcast today, Mother." Akitada rose and bowed. I shall visit again when you are feeling more cheerful."

Lady Sugawara did not bother to reply.

• • •

The university was nearly deserted today because there were no classes or lectures. Akitada stopped by Hirata's room, but found it empty. The holiday was causing problems. He was anxious to get their meeting with Oe and Ishikawa over with, but could do nothing without Hirata.

In his own room a stack of student papers lay on his desk. He wondered whether he was obligated to read them before leaving, or if he should spend his last day gathering up his belongings. Postponing the decision, he took a stroll over to the students' dormitories with the vague idea of asking Ishikawa a few questions.

Things were a bit livelier here. Some of the youngest boys were gathered in a grove of pine trees where they were noisily occupied with large sheets of colored paper. Akitada approached curiously and realized that they were building kites.

He glanced up at the clear sky. Fluffy clouds travelled quickly on the breeze. It was perfect kite flying weather. Watching the boys, he saw the first trial kite rising from the line of a madly dashing youngster. It soared briefly, then made a sudden plunge, and became entangled in the top of one of the pines.

Akitada walked over. The pine looked like a good climbing tree. On an impulse, he took off his robe and fastened the legs of his full trousers around his knees. Pulling himself up to the lowest branch, he began to climb. But the kite was too far up. The weaker branches near the top would not hold his weight. As he paused to ponder the situation, something plucked at his trousers.

"Excuse me, sir," said one of the boys, peering up at him. "Would you mind if I passed you? My kite is stuck up there."

Akitada moved aside and watched as the agile little monkey reached the kite, plucked it loose, and let it down to his waiting comrades.

"Excuse me, sir," said the boy again, passing him on the way down.

Feeling foolish, Akitada watched him scramble quickly back to the ground. Had the boys not realized that he had been trying to get the kite? What had gone through the child's mind when he saw one of the masters climbing a tree? Humbled, Akitada descended more slowly and put his robe back on. Climbing trees after kites was clearly no longer proper at his age.

At one of the dormitories he found an older student sitting on the steps, mending his shoes. Akitada asked him, "Can you tell me where I might find Ishikawa?"

The young man stood politely and bowed. "He is not here today, sir. I saw him leave before dawn. He was carrying a bundle, so I assumed he was going on a short trip."

More delays! Ishikawa would not be back till late. Akitada strolled back towards the boys with their kites. Suddenly his eyes fell on the small figure of young Minamoto, sitting quietly on the veranda outside his dormitory room. He appeared engrossed in a book, but stole surreptitious glances at the other boys. For a moment Akitada wondered why he was not with them; then he remembered that rank and recent bereavement probably prevented him from joining in games that should have been a natural part of his young life. The young lord's continued isolation from the other children pained Akitada.

Shaking his head helplessly, he left the enclosure by its north gate and crossed the street to the school of music. Sato must be in, for he could hear the sounds of his lute. This time the melody was even more lilting than on the last occasion. As Akitada walked towards the music, a second lute joined in. Another student? No. From the delightful harmony which ensued, it was clear that two master musicians had met.

Akitada approached quietly and seated himself on the veranda outside Sato's room to listen. He wished, not for the first time, that he could play like that. It was wonderful to become lost in music. All one's cares seemed to drop away. As a youngster he had briefly practiced the flute, and he had had some lessons as a student, but then more important matters had taken up his time and he had neglected his practice and given up.

After a little, the music ended and there was some subdued talk. Embarrassed, Akitada rose, cleared his throat and went to greet the music teacher.

Sato was again with a woman, this one older and more elegant than the murdered girl. They had not heard him, and this time surely there was no doubt that the teacher and his visitor were lovers. Both were seated cross-legged, their lutes resting in their laps, and their heads inclined towards each other. But it was more than their physical proximity to each other. They exchanged soft glances and the woman reached out to caress Sato's cheek.

Taken aback, Akitada retreated, but he had already been seen. The couple jerked apart, staring at him. Making a bow, Akitada apologized for his intrusion. The woman blushed and assumed a more decorous kneeling posture. Her beauty, though mature, was poignant. Akitada explained lamely, "I heard the music and could not resist it."

"It's a holiday," snapped Sato angrily. "Don't you have a private life?"

The woman got up with her lute and slipped out without a word or gesture to either of them.

"I am sorry," Akitada said again, looking after her. "Believe me, if you are worried about my complaining about your private lessons, your secret is safe with me. But this lady played so well that she can hardly be your pupil." He flushed, thinking how this must sound to Sato.

Sato looked at him without expression. "She is a fellow musician and acquaintance who dropped by for a chat," he said. When Akitada made a move to leave also, Sato became hospitable. "Will you take some wine?"

Somewhat surprised, Akitada accepted readily. Sato was an interesting enigma. Akitada sipped his wine and said, "I assume the police captain has talked to you about the girl who was murdered in the park. Could you provide him with a name?"

"Yes. Her name's Omaki. I had to go and identify her body. Poor little wench!" Sato took a big gulp of his wine. "I suppose I've got you to thank for the police interest?"

Akitada met his eyes calmly. "I am afraid it was unavoidable. My servant and I found her, and I remembered meeting her with you."

Sato looked away. "Yes, I see. I suppose it couldn't be helped. She was a silly girl, but she didn't deserve to die so young." He grimaced. "It was a bit embarrassing, though. I met her in the Willow Quarter."

"She was a prostitute?"

"Not everybody in the Willow Quarter is a prostitute," snapped Sato angrily. But he calmed down quickly and sighed. "Poor Omaki. She was training to become an entertainer. If you ask me, she was on her way to becoming a prostitute when she died. It was her karma. Her father's a poor man, an umbrella maker called Hishiya. They live in the sixth ward. The mother had died and he remarried. It's the usual story: the second wife did not get along with the grown daughter. The girl threatened to sell herself to a brothel rather than stay home as a servant to the new wife. The father, who's a decent man, came to me one evening. Told me the girl played the lute and asked if I could get her a job. I listened to her play. She was untrained but not bad. The long and the short of it was that we made an arrangement by which I got her a job in a place I know, and she paid me for a few lessons. She learned quickly. Anyone else would have succeeded. But for her? All wasted! Poor silly chit!"

He filled his cup again, drank deeply, and stared out the door. Akitada sipped his wine slowly. He did not believe either the sentiments or explanations. Sato had become positively chatty. The man's behavior, his reputation, the fleshy, sensuous lips and soulful eyes– all were at odds with the detachment he pretended. No, Sato was a womanizer, perhaps a murderer, not a humanitarian.

"Did you know of anything that might help the police find her killer?" Akitada asked.

Sato shook his head. "I doubt it. I knew she was with child, foolish girl. That meant the end of her career just as it was starting. But she didn't seem to care. When I asked her about the child's father and her plans, she closed up. Actually, if anything, she seemed more cheerful, or excited, than before." He paused and thought. "There was one thing I told that captain. I saw her with one of the students here. Maybe that young rascal was the father of her child. He used to moon about the place where she worked. Damned youngsters ought to keep their heads in their books! Though this particular one was hardly a dashing figure. Can't imagine what she saw in him!"

There was a sharp twanging sound, and Akitada's eyes went to the music teacher's hands. They were clenched tightly around the neck of the lute. Sato followed his glance and immediately relaxed his long fingers. They looked powerful from twisting tight lute strings, and agile from many hours of practice. Powerful and agile enough to twist a piece of silk around a woman's neck and strangle her to death?

"Oh, I can see what's going through your mind," Sato said angrily. "It wasn't my brat and I had nothing to do with her death. And having said that much, I have no intention of pursuing the subject."

Akitada reddened, disclaimed such suspicions, and changed the subject to the previous evening. But his comments about Oe's argument with Fujiwara seemed to irritate Sato more. He growled, "I wasn't there, and I don't care a monkey's fart what that bastard Oe does. Serves him right, if he made a mess of himself." Grasping his lute, he got to his feet.

It was a signal that the conversation was over. Akitada rose also and left to return to his room, where he found a bleary-eyed Tora waiting for him.

"You look terrible," Akitada said sourly, eyeing Tora's unshaven chin, his dishevelled hair and the bloodshot eyes. "Where have you been? Have you had any sleep?"

"None at all!" Tora grinned. "Sleep isn't everything. As you'd find out if you tried it. You know, you should sleep with a woman more often. It may not be restful, but it's a great deal better than sleeping alone. Not having a woman saps a man's vital essence after a while. I may look worse than you, but my vital essence is in top shape, thanks to the prettiest and most talented female you ever saw. Oh, what a body that girl has . . . and the things she does with it! There's a position she calls 'monkeys swinging from a branch' where she—"

"Enough!" Akitada roared in a sudden fury. "Watch your tongue when you speak to me! And spare me the details of your sordid affairs! Seimei is quite right. I have spoiled you. Your excessive familiarity is beginning to grate. And now you are becoming insolent. Not only do you lack all respect for your betters, but you don't seem to do much work. Why did you not return to the house last night and report to your mistress for your duties this morning?"

Tora gaped at his master speechlessly.

"My mother complained about you," blustered Akitada, "and I did not know what to say. Be careful! If you try my patience too much, I shall abandon you to the streets."

Looking pale, Tora scrambled to his feet. "I'll go right now, sir," he mumbled, eyes averted and his voice tight with shock.

Immediately ashamed of his outburst, Akitada bit his lip. "Well, er, maybe you'd better wait a little before showing up at home. Er . . . do you know anything about building kites?"

"Making kites? Of course! And flying them! When I was a kid, I was champion in my village two years running. Why?"

"Some of the younger students are making kites in the dormitory courtyard. I think they must plan to fly them today. There is a good breeze for it. I want you to go over and talk to the Minamoto boy. He is probably still on the veranda pretending to read a book. You might see if you can get him interested in kites."

"A boy who's not interested in kites? You must be joking!" Tora paused abruptly and said, "I beg your pardon, sir. I'll take care of that right away." He rushed out, then stuck his head back in. "Oh, I forgot. I've solved your other case for you. The dead girl's name is Omaki. She played the lute in one of the wine houses in the Willow Quarter until she was fired."

"I know, and that hardly solves the case," Akitada said. Tora's face fell. Hanging his head, he turned to leave, when Akitada added, "All the same, it was good of you to ask around. We'll talk about it later."

When Tora was gone, Akitada sat down heavily and stared at the spray of white hollyhocks that survived, somewhat crushed, in a wine cup full of water on Akitada's desk. Perhaps Tora had a point. A man was not meant to spend his life alone unless he was a monk or hermit, and Akitada had no interest in the contemplative or spiritual life. What was it Sato had said? He had asked if Akitada had a private life. Against his better sense, he closed his eyes and thought of Tamako in her Kamo finery. It was a revelation how enchanting her face seemed to him now, since he had really never realized it before. And she had a very graceful figure, slender, with elegant shoulders and a most enticing neck when she turned her head. The image of that white neck with a delicate rosy ear half hidden by the silky black hair was extraordinarily erotic, and he called himself to order sharply, ashamed that Tora's tussle with a common prostitute should have caused him to think with physical desire of the young woman who had been like a sister to him. He reached for the student papers.

Professor Hirata stopped by when Akitada was halfway through the stack of essays. He complained of not being able to find Oe. "Have you spoken to Ishikawa yet?" he asked.

"No, he left early this morning. It is a holiday, and he may be visiting friends." Akitada found it difficult to behave normally around Hirata and had to force himself to carry on a conversation. "How did the rest of the contest go?"

"I left after the final competition. They tell me that the party went on into the night, with boat rides on the lake and impromptu poems praising the moon. Incidentally, Fujiwara won another prize in the love poetry category and was declared this year's poet laureate. Oe will be furious when he finds out. He has expected that honor for years now. For all we know he will contest the results on the grounds that he was forcibly removed by Fujiwara before he could present the rest of his work."

Akitada smiled thinly. "Surely he has been embarrassed too thoroughly to show his face in public for a while."

Hirata nodded. "Besides there is the matter of the last examination. We can exert a certain amount of control over him in the future. I have thought about that. It will surely be enough if we confront Oe and Ishikawa with our knowledge. We will insist that Ishikawa stop his blackmail demands and that Oe remove himself from judging future examinations. I admit it hardly punishes their behavior, but there is nothing we can do to rectify what happened in the spring. The damage is done, and we cannot bring back that poor young man who killed himself. Besides, reversing the results at this time will permanently damage the reputation of the university." Hirata looked at Akitada anxiously.

Blackmail begets blackmail, thought Akitada. But he said, "Certainly. As you wish."

There was a pause. Hirata bit his lip. His face betrayed surprise and worry at Akitada's lack of interest. He was about to pursue the subject, when Tora burst into the room.

"You'll never guess what just happened!" he cried. "The police arrested one of the students for the murder."

"No!" cried Hirata. "Who is it?"

"It's Rabbit." Tora looked at Akitada. "You know, the fellow I told you about. The one who got into a fight with another student in the kitchen that day." Tora fumbled in his sash and produced a crumpled piece of paper. "Here!" he said, extending it to his master, "he wrote you this note."

Akitada unfolded it. It was short, stating simply that the author was innocent of the crime, implored Akitada's help, and offered to pay for it. It was signed Nagai Hiroshi. He passed the note to Hirata.

"Poor boy!" cried Hirata, looking shocked. "That nice, awkward youngster. Who could possibly believe him capable of murder? There must be some mistake."

Akitada recalled the brief encounter at the gate the afternoon before, and had the sinking feeling that there was no mistake. "What about this fight you saw, Tora?" he asked.

"I think the other fellow had been making fun of his crush on a woman. But I'll lay you a bet, sir. If Rabbit was that girl's lover, I'll give up women for good!"

Amused in spite of himself, Akitada murmured, "I don't want to create difficulties for the young man, but I am tempted to hope you would lose."

Tora looked hurt. "I know I'm right. She was a good-looking skirt, and he looks like a cross between a mangy rabbit and a crane. He walks like some long-legged bird that's stepping on broken reeds, and his big ears are flapping in the breeze while his teeth are looking for his chin. Believe me, no pretty girl in her right mind would be seen with something like that!"

"You exaggerate," said Akitada, but he recalled Sato's words about Omaki's unlikely boyfriend. "I met the young man at the gate yesterday. He looked very ill."

"Hah!" cried Tora. "Maybe he did fall for her! Anyway, the police searched his room and found a bunch of stuff he had written. They took it all away with them." A thought struck him. "That just goes to show the trouble you get into with an education. It's his writing poems about the girl that got the fellow arrested."

Akitada's eyes met Hirata's. They smiled. "What do you think I should do?" Akitada asked the older man. "I hate to meddle in Captain Kobe's business again so soon after we had words over the beggar he arrested."

"What about the beggar?" Tora interrupted.

Akitada frowned at him and continued, "Besides there is our own problem. You know I want to get that matter settled as soon as possible. Getting involved with this student may keep me here indefinitely."

Hirata avoided his eyes. "Your fame as a righter of wrongs seems to have spread to the students," he said lightly. "Of course you must try to help Hiroshi. A young man's life and his family's honor are at stake. Even the reputation of this university is less important than that." He paused. "I recall meeting Hiroshi's father when he brought the youngster. Mr. Nagai is a poor schoolmaster in Omi province. The boy is the only son of five children, and I am sure the family is making many sacrifices to pay for his studies."

A scenario not so different from that of the student who had committed suicide. But there was little point in resenting Hirata's hypocrisy or his relief that Akitada would be trapped into staying on after all. He could not refuse the student's appeal. Akitada sighed. "Very well. I shall go to see him."

"What about me?" asked Tora. "You will need me to investigate, but the young lord is waiting to go buy paper and bamboo sticks for our kites."

Akitada turned to Tora with amazement. "You mean you have already won the boy's confidence?" he asked.

"Oh, it was easy enough. For all he's a lord, he was dying for someone to talk to. When I told him about the kite I won my first district contest with, he couldn't wait to try to build one like it."

Akitada clapped Tora on the shoulder. "Excellent!" he cried. "You did better than any of us! I have been trying for many days now to talk to the boy and failed miserably. You must have a special touch with children." Tora preened a little. "Under the circumstances," continued Akitada, "you must keep your promise to Lord Minamoto. But later today, when you are done with the kites, go to see the girl's family. Professor Sato tells me that Omaki was the daughter of an umbrella maker called Hishiya. They live in the sixth ward. She was unmarried and pregnant, as you know, but apparently not particularly worried about her future. Perhaps you can find out something about the men in her life."

• • •

When Akitada got to the municipal police headquarters, he discovered to his relief that Kobe was out. Even better, one of Kobe's men recognized him and took him to see the student Nagai.

He found him sitting on the dirt floor of a small, damp cell, lit by a single slit of a window near the ceiling. When the door opened with a rattle of locks and keys, Nagai raised red-rimmed eyes. Akitada was startled anew by the pathetic ugliness of the boy's features, wet and swollen with weeping. Akitada, ashamed of his reaction, greeted the boy with a smile.

The young man stumbled to his feet, but the chains which bound his wrists and ankles made this difficult.

"Please sit down!" Akitada said quickly and seated himself on the bare floor. "I received your note. Exactly what sort of trouble are you in?"

"I am accused of having killed Omaki." The youngster swallowed hard, a prominent Adam's apple bobbing disconcertingly in his long neck. "As if I could!" he cried. "I worshipped her! But things look very bad for me. Only you can help me, sir! They say you have solved many difficult cases. Please, for the sake of my family, clear my name! I don't care anything about myself, but my poor parents and sisters . . ."Tears started down his cheeks. He sniffled, and wiped ineffectually at a running nose with a sleeve already wet with tears.

Akitada regarded him with pity. Tora's estimation had been cruel but correct. The homely face, now red-splotched, the dripping nose and lax mouth made him a most unlikely romantic hero. Such a young man must feel deeply the hurt of rejection by the one person he idolizes. And a girl like Omaki, pretty, pert, ambitious, would have considered the adoration of this youngster, with neither looks nor fortune, a tedious joke. Had she taunted him, tried his patience and devotion too far until he had killed her? Was he the student she had been in the habit of meeting in the park? Or had he followed her and, finding her with another student, lashed out in anger at her betrayal?

"What made the police fix on you as a suspect?" Akitada asked.

"They talked to some of the students and my name came up." Nagai hung his head again. "One of them found a poem of mine and told the others. I was angry at the time, but perhaps it was very foolish of me to think that such a pretty girl could like me. When we first met, she was really nice to me. And she seemed to enjoy going for walks in the park. She told me all about her music, and I told her about my family."

Akitada's heart went out to the poor infatuated youngster. But pity would not clear Nagai of the charges against him. He said, "Your name being mentioned by the other students explains why the police talked to you, but it does not account for your arrest. What else happened?"

Nagai sighed and gave Akitada an imploring look. "We quarrelled, Omaki and I. The day she . . . before she was found. Someone overheard us. And then, when the police searched my room, they found the poems and my diary." He hung his head, twisting his red, bony hands.

"You quarrelled in the park?"

Nagai looked up. "Oh, no!" he cried. "We did not go to the park that day. We talked in the university, just inside the dormitory enclosure. She had finished her lute lesson. I usually waited for her there."

"What did you quarrel about?"

There was a pause. Then Nagai said, "I asked her to marry me. I know I should not have asked her without my father's permission. My family counts on me to do well in the examination. But I was afraid they would forbid it, and I couldn't wait. Well, I thought Omaki needed someone . . . and I thought if I could take the next examination instead of waiting my turn, I might pass. Even if I did not do very well, I could still become a schoolmaster back home. And Omaki and I could live with my parents. She could help my mother, while my father and I could run the school." He shook his head sadly. "I should have known I was being foolish."

Akitada said dryly, "I take it she was not overjoyed by your offer."

An expression of acute pain passed over the young man's face. "She laughed at me! She wanted to know how we would live until I passed the examination. When I suggested that she might give lute lessons or play for guests just a little while longer, she got angry and called me names. She called me r . . . rabbit because of my ears and teeth, and . . . ugly toad and worse things." He flushed and looked at Akitada earnestly. "She was not herself. You see, she was expecting a child. I am told women become very high-strung in that condition."

"Was it your child?"

Nagai hesitated, then shook his head. "No. We didn't . . . it must have happened before we met. I never asked. Some unprincipled person must have taken advantage of her and then deserted her. When she first confided in me, I got the idea that she might consider being married to someone like me."

He looked so completely humiliated that Akitada's heart contracted with pity and he felt increasingly angry with the dead girl. Finding herself pregnant, she meant to marry the infatuated student, but later decided he was not good enough. This change of heart, if you could call it that, confirmed Sato's impression that she had seemed untroubled by her pregnancy and even pleasantly excited. Something had happened to make Hiroshi Nagai dispensable, so that she had felt free to mock and revile his unselfish and sincere devotion before sending him on his way. Her behavior gave him a strong motive to kill her. But Akitada wondered what had happened to change her expectations so drastically.

He told Nagai, "I will try to help you, but you must tell me all you know about her private life, her friends and her family."

The student bowed deeply and expressed his gratitude. Then he said, "I am afraid I don't know much." Looking a little uneasy, he confessed, "I met Omaki in the Willow Quarter. I know it is against the rules for students to visit there, but some of the others took me along one night. We climbed the wall. I was very nervous."

Akitada nodded understandingly. No doubt the lonely, unpopular youngster had accepted the invitation eagerly, even against his better judgment.

"Omaki had a job playing the lute in one of the wine houses we went to. She played as beautifully as she looked." He smiled a little at the memory. "I kept going back there as much as I could, and one day she noticed me and smiled. After her performance I got up the nerve to talk to her. We took a walk by the river. I thought she was wonderful. She talked about herself, how poor her family was and how very unhappy she was. Her stepmother beat her and made her rise before dawn to do all the work, even when she didn't get home from her job in the wine house until very late. She told me many times she wanted to run away or kill herself." Nagai sighed deeply.

"What about the people where she worked? Did she tell you about them?"

"Not much. The auntie at the Willow was always wanting her to sell herself, but Omaki wanted to be an entertainer. I know some people have said bad things about her, but that proves she was a decent girl, doesn't it, sir?"

Akitada did not share this conviction, but nodded. "Who said what about her?" he asked.

"Oh, some of the fellows I went out with. But they were lying. They were always making fun of me." With a bashful glance at Akitada, he said, "I thought maybe they were jealous of me."

"I see. Was there anyone else who knew her well?"

"She was taking lute lessons from Professor Sato. Professor Fujiwara and Professor Sato often go to the Willow. The first time I saw them I was frightened, thinking they would turn us in, but the others told me that I had nothing to worry about. Anyway, Professor Sato being an instructor of the lute, I pointed him out to Omaki. She managed to get him to take her as a private student. That was wonderful, because then I got to see her during the day. We'd always meet after her lesson and sometimes we'd stroll over to the park. Until that last day." He sighed and wiped his eyes again.

"What about other people? Friends, coworkers, regular patrons?"

"There is another lute player at the Willow, but they did not get along. Omaki said the woman was too proud. And the girls were silly and common."