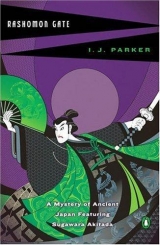

Текст книги "Rashomon Gate "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Rashomon Gate

A Mystery of Ancient Japan

I. J. Parker

St. Martin's Minotaur

New York

www.eBookYes.com

RASHOMON GATE. Copyright © 2002 by I. J. Parker. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010.

www.minotaurbooks.com

eISBN 0-312-70746-0

For Tony

Acknowledgments

Several wonderful people have helped Akitada into the world. My most profound thanks go to my friends and fellow writers Jacqueline Falkenhan, John Rosenman, Richard Rowand, and Bob Stein, who have read and sometimes reread the draft, making suggestions and giving me moral support when I needed it. Their kindness and expertise were equally inspiring. I am also indebted to Yumiko Enyo for her help with matters pertaining to Japanese customs. Finally, I must thank two consummate professionals: my agent, Jean Naggar, and my editor, Hope Dellon.

Characters

Japanese family names precede given names.

MAIN CHARACTERS

Sugawara

Akitada ~ Clerk in the Ministry of Justice

Seimei

~ Family retainer of the Sugawaras and Akitada's secretary

Tora

~ A former highwayman, now Akitada's servant

CHARACTERS CONNECTED WITH THE CASES

Hirata

~ Professor of law

Tamako

~ His daughter

Oe

~ Professor of Chinese literature

Ono

~ Assistant to Oe

Takahashi

~ Professor of mathematics

Tanabe

~ Professor of Confucian studies

Nishioka

~ Assistant to Tanabe

Fujiwara

~ Professor of history

Sato

~ Professor of music

Sesshin

~ Buddhist monk; president of the university

Ishikawa

~ Graduate student

Lord

Minamoto ~ Student

Nagai

~ Student

Okura

~ A former student

OTHERS

Lord

Sakanoue ~ Lord Minamoto's guardian

Kobe

~ Captain of the Metropolitan Police

Omaki

~ A musician in the Willow Quarter

Mrs. Hishiya

~ Her stepmother

Auntie

~ The manageress of the Willow wine house

Madame

Sasaki ~ A talented performer

Kurata

~ A merchant and customer of the Willow

Hitomaro

~ An unemployed swordsman

Genba

~ A former wrestler

Lords

Yanagida, Abe, Ono and Shinoda ~ Prince Yoakira's friends

Kinsue

~ Prince Yoakira's servant

Umakai

~ A beggar

Preface

Rashomon Gate is the story of Sugawara Akitada, a fictional minor official in the Japanese government during the eleventh century. At this time he is almost thirty years old and, to the regret of his mother, neither married nor successful in his career in the Ministry of Justice. On the other hand, he has a knack and manifest penchant for solving crimes, a trait which has gained him the friendship of men of high and low degree.

While the characters and events are imaginary, certain historical facts about the capital city of Heian Kyo (modern Kyoto), the university system, law enforcement, and the customs and tastes of the eleventh century have been carefully incorporated into this tale, which involves Akitada in the solution of a series of puzzles during the courtship of a reluctant bride.

The story of the disappearing corpse was suggested by two tales (numbers 15/20 and 27/9) in the late-eleventh-century collection Konjaku Monogatari.

The maps of Heian Kyo and of the university are based on historical sources, and the other illustrations are intended to resemble Japanese woodcuts. A historical endnote gives additional information about pertinent aspects of life at the time.

Prologue

Rashomon

The corpse was headless. It lay huddled in a dark corner where only the faint light of the moon filtering through the wooden shutters picked out the paleness of naked skin from the prevailing gloom.

A dark shadow moved in the gray light, and an ancient voice rasped, "Look around for the head!"

"What for?" growled another voice. A second shadow joined the first. "It's no use to anybody but the rats." The speaker cackled suddenly. "Or hungry ghosts. For playing kickball."

"Fool!" The first shadowy creature turned and, for a moment the moonlight caught a wild mane of tangled white hair. It was a woman, crouching demonlike over the body, her claws quickly tucking some white, soft fabric inside her ragged robe, "I want the hair."

"Are you blind? That's a man!" protested her male companion. "There's not going to be enough hair on it to get a good grip." He leaned to peer at the body. "Besides, he's an old one."

"He's been well-fed." She tweaked the corpse's belly and slapped his buttocks. "Feel his skin! Soft as silk, eh?"

"So? Much good that's gonna do him. Poor beggar's dead."

"Beggar?" the woman shrieked with derision. "Touch his feet! You think that one walked? Not likely. Rode in coaches and palanquins, I bet. Now go find that head! He'll have long hair all twisted up neatly on top. That's worth ten coppers at least. The good people don't cut it off like you 'n me. Their women have hair so long they can walk on it. I wish we'd get one o' them!"

The man snickered. "Me, too. I'd know what I'd do to her!" he said and smacked his lips suggestively.

The old woman gave him a kick.

"Ouch!" He cursed, then backhanded her viciously. In a moment they were fighting like a pair of hungry alley cats. He gave up first and retreated a few steps.

She rearranged her robe, making sure she still had her booty, then snapped, "We gotta get out o' here before the patrol comes. Go look for that head! It's gotta be somewheres. Maybe it rolled behind that bunch o' rags back there."

"Them's not rags!" muttered the old man, poking the bundle with his foot. "It's another one."

"What? Let's see!" She scurried over, peered and straightened up disappointedly. "Just an old crone. Nothing worth taking on her. Starved to death from the looks o' her, and cut her own hair off long ago. Where's that head?"

"I tell you, it's not here," whined the man, poking around in all the corners.

"Well," she said in a tone of outrage, "I don't know what the place is coming to. Now they're not even in one piece. You suppose the patrol will call the police?"

"Naw," said her companion. "Too much trouble for the lazy bastards. You done?"

"Guess so." She looked about. "Two tonight?"

"Yeah. You get anything?"

"A loincloth and socks," she muttered, secretly touching the fine silk of the dead man's undergown which nestled between her sagging breasts. "Bet some bastard made off with the head and the rest o' his clothes. Let's go!" She shuffled towards the doorway.

"Wonder who the old guy was," he said as he followed her down the stairs.

"What do you care?" she snapped. On the ground floor, she peered cautiously into the street from behind one of the huge pillars. "When that one was alive he'd not waste a thought on you 'n' me! Well, now he's dead and his socks'll pay for our supper and that loincloth'll buy some cheap wine. It all comes out even in the end."

One

The Wisteria Arbor

Akitada straightened up and stretched his tall, lanky frame wearily. He had spent the best part of this beautiful spring day bent over dusty dossiers in his office in the Ministry of Justice. With a sigh he rinsed out his brush and reached for his seal.

Across the room, his secretary Seimei rose to his feet. "Shall I bring the case of the Ise shrine versus Lord Tomo next?" he asked eagerly.

Seimei was over sixty and deceptively frail-looking with his nearly white hair and a thin mustache and goatee. Akitada marvelled, not for the first time, that his old friend seemed to be positively thriving on this tedious work. Seimei was the only one left of the family retainers of the Sugawara family. He had risen in the household, by his own effort and Akitada's father's encouragement, to become steward and clerk. When his master had died, leaving behind a sadly diminished estate, a widow, two daughters and a minor son, Seimei had looked after all of them devotedly until Akitada had finished his education and gained his first government position. Recently, after Akitada's promotion to senior judicial clerk in the ministry, his young master had chosen him as his personal secretary.

"Must you?" Akitada sighed. "I have been cooped up with these documents for upward of too long and don't think I can bear another minute of it."

"The path of duty is near, but man seeks it in what is remote," Seimei remarked primly. He was much given to sententious sayings. "Even the ocean has grown a drop at a time. As Master Kung says, serving His Majesty must be your first duty." But seeing Akitada's drawn face, he relented. "A brief rest is what you need. I shall brew some tea."

They had acquired the taste for tea only recently and the herb was prohibitively expensive, but Akitada found it more refreshing than wine and Seimei swore by its medicinal properties.

When the older man returned with two cups and a steaming pot, Akitada was pacing the floor. Outside a bird was singing. "I wonder," Akitada said, listening wistfully, "if we could not find the time to ride out into the mountains." He accepted a cup of tea and drank thirstily. "I thought we might visit the Ninna temple."

"Ah! A strange story, that one," Seimei said with a nod. "It's been several weeks now, and people haven't stopped talking about it yet. I am told the emperor himself went to visit the place and inscribed a plaque with his august sentiments. It is said that Prince Yoakira was instantly transported into Buddhahood through the fervency of his prayers. Now people are streaming to the temple praying for miracles."

"And of course the temple has benefited from their contributions," Akitada remarked dryly.

Seimei gave his master a sharp look. "Of course," he said. "But there is also some talk about demons devouring his body. They say he had many warnings from the soothsayers lately."

"Miracles! Demons! Ridiculous. There should have been a thorough investigation."

"There was. The prince arrived with a small party of friends and retainers, and entered the shrine alone by its only door; he chanted for an hour while his companions sat outside, waiting and watching the door. When he finished his devotions but did not come out, his closest friends went in together. They found nothing but his robe. The monks were called, and later the police and the imperial guards. All of them searched the temple and its surroundings for days without finding a trace of the prince. Finally the monks petitioned that the emperor acknowledge a miracle, and so he did."

"Nevertheless I don't believe it!" Akitada pulled his earlobe, frowning. "There must be an explanation. I wonder if . . ."

Suddenly a shouting match erupted outside the ministry.

"That sounds like Tora!" Akitada was at the door to the veranda in a few strides, Seimei right behind him.

In the courtyard two men were facing each other threateningly. One was small, still in his twenties, with a weak face not markedly improved by a mustache, and dressed in the shimmering silk and the formal lacquered headgear of a court official. The other was not much older, tall and muscular, handsome, but dressed in a plain cotton shirt and trousers.

The courtier was advancing, his wooden baton raised to strike, when the other said in a dangerously low voice, "If you touch me with that toothpick, puppy, I'll shove it down your throat and stop that nasty mouth of yours for good!"

The official paused uncertainly. Flushed, he sputtered with rage, "You . . . you . . . would not dare!"

The tall man bared a handsome set of teeth and took a step toward him. The courtier retreated several feet and looked about for help. His eyes fell on Akitada and Seimei who had stepped up to the balustrade of the veranda.

"What is the matter, Tora?" Akitada asked the former highwayman who was now his houseman.

The tall young man turned. "Oh, there you are." He waved to them with a grin. "We sort of collided at the corner, me being in a hurry, and him not looking where he was going. I said I was sorry, but the pretty boy threw a temper tantrum, called me names, and wanted to hit me with his toy."

"Is that uncouth savage your servant?" the stranger demanded in a voice trembling with fury.

"Yes. Were you injured in the encounter?"

"It is a miracle I was not. I demand that you punish this person immediately and forbid him to enter the imperial enclosure in the future. He is clearly unable to recognize his betters."

"Did he not apologize?" Akitada asked.

"What does that signify? If you do not do as I ask, I shall have to call the guard from the gate."

"Perhaps we should discuss the matter further. By the way, my name is Sugawara Akitada. May I know yours?"

The little man drew himself up importantly and recited, "Okura Yoshifuro. Secretary in the Bureau of Ranks, Ministry of Ceremonial. Junior seventh rank, lower grade. I am on my way to speak to the minister and have no time to waste with minor officials."

Akitada raised his heavy brows. His normally pleasant, narrow, aristocratic face assumed a haughty expression. "In that case you may wish to discuss the matter with Counsellor Fujiwara Motosuke, a member of the council of state. He is by way of being a special friend to Tora and myself and will vouch for us."

The color receded from the other man's face. "Naturally I would not dream of troubling a man of the counsellor's standing," he said quickly. "Perhaps I have been rather hasty. The young man has apologized, as you rightly reminded me. It behooves people of rank to be understanding of the feelings of the common man. Did you say your name is Sugawara? A pleasure to make your acquaintance, sir. Hope to meet again." With a polite bow, he turned and rushed off so quickly that his lacquered headgear slipped over one ear.

Tora opened his mouth to shout with laughter, but Akitada cleared his throat warningly and waved him inside.

"Well, I guess you showed him who's in charge!" grinned Tora as soon as the door closed behind them.

"What possessed you to pick a fight with an official?" Seimei cried. "You will surely cause your master trouble!"

Tora bristled. "Maybe you think I should've let him hit me?" he demanded.

"Yes." Seimei wagged his finger at him. "You should indeed. How can you give yourself such airs? Remember that it is always the biggest dew drop that falls first from the leaf."

"What was so urgent?" Akitada interrupted.

"Oh."Tora pulled a folded paper from his shirt and handed it over. "There's this letter from Professor Hirata. A boy brought it to your house just when the carpenters got there to start work on the south veranda. They look like a proper bunch of louts, so I need to get back."

Akitada unfolded the letter. "Well, you can go back now," he said when he had read it. "Heaven forbid the louts should do violence to my mother's favorite veranda. But this time walk!"

When Tora had gone, he said to Seimei, "I am invited to dinner. I know I should have visited them before, but . . ."He let his voice trail off uncertainly. As usual, his conscience smote him.

"A very kind gentleman, the professor," Seimei nodded. "I well remember the time when you went to live with him. How is the young lady? She must be quite grown up."

"Yes." Akitada pondered. "Tamako must be about twenty-two by now. I have not seen her since my father died and I moved back into our home." Akitada's mother disapproved strongly of any ties with the Hiratas, but he could not honestly blame his reluctance to see Tamako on Lady Sugawara's snobbery. Too much time had passed, and he was afraid that they would not have anything to say to each other any longer. He said, "The professor writes that he needs my advice. He sounds worried. I hope nothing is wrong." Sighing, he said, "Well, Seimei, old friend, back to work!"

Two hours later Akitada carefully dried the ink on the last sheet of commentary on the legal intricacies of the case and remarked, "Apart from the exalted status of the litigants, this is a simple suit. May I take it that we have whittled down the backlog of cases under review?"

"Yes. There are only another twenty dossiers, all of them minor matters."

"In that case, Seimei, we are entitled to make an early evening of it. Let us go home!"

• • •

The sun was already slanting across the green-glazed roofs of the government buildings, when Akitada, on his way to the Hiratas, walked along Nijo Avenue, past the red pillars of the gate leading into the Imperial City. He squinted into the bright light, dodging the steady stream of clerks and scribes flowing through the gate on the way to their homes in the city.

From this gate, called Suzakumon, Suzaku Avenue stretched south to Rashomon, the great two-storied southern gate of the capital city. Along its entire length, Suzaku Avenue, more than two hundred feet wide and bisected by a wide canal, was lined with willow trees. A multitude of people, native and foreign, of high and low degree, pedestrians, ox carts and horsemen moved along this main thoroughfare all day long. Akitada thought it the most beautiful street in the world.

To the west, ahead of him, the pale greens of many trees in their spring foliage screened one of the residential quarters. From this vantage point the area looked like a vast beautiful park, but Akitada knew better. The northwestern quadrant of the city had, like its eastern counterpart, been planned for the palaces, mansions and villas of the "good people," the great noble families, the high-ranking court officials, and members of the imperial clan, while the southern two thirds of the city were occupied by the common people, and by the markets and amusement quarters. For no apparent reason, people had begun to abandon the western city and crowded into the eastern half or moved to the countryside.

Their palaces and villas had burned down or fallen into decay. Many of the humbler homes had been abandoned to squatters and cutthroats. Only the trees and shrubs had thrived, and a last few respectable families, like the Hiratas, lived quiet, isolated lives there.

As Akitada passed down street after street, some of them bisected by canals and crossed by simple wooden bridges, he saw that several more homes had become empty since he had last walked this way. He wondered how safe Tamako was when her father was teaching at the university.

To his relief, the Hirata villa appeared unchanged. Its wall had been kept in good repair, and the same gigantic willows flanked its wooden gate. The scent of wisteria blew over the wall on a soft breeze. With a sense of homecoming Akitada raised his eyes to the elegantly brushed inscription over the gate: "Willow Hermitage."

A white-haired servant, bent with age, opened the gate and greeted him with a wide, toothless smile. "Master Akitada! Welcome! Come in! Come in!"

"Saburo! It is good to see you again. How is your health these days?"

"Well, there's a pain in my back and my knees are stiff. And my hearing's going, too. "The old man touched each defective part in turn and then broke again into his big grin. "But it will have to get much worse than this before I'm ready to go. No man could ask for a better life than mine. And now here you are, come back a famous man!"

"Hardly famous, Saburo, but I thank you for the welcome. How is the professor?"

"Pretty well. He's waiting in his study for you, Master Akitada. But the young lady asked to speak to you first. She's in the garden."

As he made his way along the moss-covered stepping stones, Akitada basked in the warmth of the old servant's welcome. To be called "Master Akitada" again, just as if he were the son of the family, brought back the happy year he had spent here as a youngster.

When he rounded the corner of the house and saw a slender young woman among the flowering shrubs, he called out cheerfully, "Good evening to you, little sister!"

Tamako turned and looked at him wide-eyed. For a moment an expression of sadness passed over her pretty face, but then she smiled charmingly and ran towards him, hands outstretched in greeting.

"Dear friend! Welcome home! You make us very happy. And you look so distinguished and very handsome in that fine robe." She stopped before him, her hands in his, and smiled up at him.

Akitada was lost in surprise. She had become quite lovely, with that slender face and neck and an elegant figure.

"How is it that you are not married yet?" he blurted out.

She released his hands and looked away. "Perhaps the right person has not asked yet," she said lightly. "But then I hear you, too, are still single." Smiling up at him again, she added, "Shall we walk to the arbor? I have a particular favor to ask of you before you see Father. And then I must go see about dinner and change into a more proper gown."

He saw, as he walked with her, that she wore a plain blue cotton robe with a white-patterned cotton sash about her small waist. It seemed impossible to improve on the picture she made and he told her so.

She turned her head slightly and thanked him with a blush and a smile. "Here we are," she said, pointing to a wooden platform under a trellis covered with flowering wisteria. The purple blooms hung in thick clusters suspended from a leafy roof.

Akitada looked around him. Everywhere plants seemed to be in flower or bud. The air was heavy with their mingled fragrances and the humming of bees. When they sat down on two mats which had been spread on the platform, he was enveloped by the sweet scent of the wisteria blossoms and felt that he had walked into another, more perfect world, one which was far more intensely alive with colors, scents and the sounds of birds and bees than any existence on this earth had any right to be.

"Something is terribly wrong with Father," said Tamako, breaking into his fancy.

"What?"

She took his exclamation literally. "I do not know. He won't tell me. About two weeks ago he came back late from the university. He went directly to his study and spent a whole night pacing. The next morning he looked pale and drawn and he hardly ate anything. He left for work without any kind of explanation, and has done the same every day since then. Whenever I try to question him, he either maintains that nothing is wrong, or he snaps at me to mind my own business. You know this is not like him in the least." She looked at Akitada beseechingly.

"What do you want me to do?"

"I have been hoping that he invited you to dinner to confide in you. If he does, perhaps you can tell me what has happened. The uncertainty is very upsetting."

She looked pale and tense, but Akitada shook his head doubtfully. "If he has refused to tell you, he will hardly speak to me, and even if he did, he may ask that I keep his confidence."

"Oh," she cried, jumping up in frustration, "men are impossible! Well, if he does not speak, you must find out somehow, and if he swears you to secrecy, you must find a way! If you are my friend, that is!"

Alarmed, Akitada rose also. He took her hands in his and looked down at her lovely, intense face. "You must be patient, little sister!" he said earnestly. "Of course I shall do my best to help your father."

Their eyes met, and he felt as if he were drowning in her gaze. Then she looked away, blushing rosily, and withdrew her hands. "Yes, of course. Forgive me. I know I can trust you. But now I must see about our dinner, and Father expects you." She made him a formal bow and walked away quickly.

Akitada stood and watched her graceful figure disappear around a bend in the path. He felt perplexed and troubled by the encounter. Slowly he walked towards the house.

The professor received him warmly in his study, a separate pavilion which was lined with books and looked out on a stand of bamboo, an arrangement of picturesque rocks and patterned gravel outside a small veranda. This room, where Akitada had worked on lessons with the professor, was as familiar to Akitada as any room in his own home. But the kindly man who had been a second father to him had changed shockingly. He looked prematurely old.

"My dear boy," Hirata began as soon as they had exchanged greetings and seated themselves, "forgive me for summoning you so abruptly when you must be very busy with official duties."

"I was very glad you invited me. This has always been a happy place for me and I have missed Tamako. She looks all grown-up and quite lovely."

"Ah, yes. I see she has already spoken to you." Hirata sighed, and Akitada thought again how tired he looked. The professor had always been tall and gaunt, with prominent facial bones made more severe by a long nose and goatee, but today there seemed more gray than black in his hair and beard, and deep lines ran from his nose to the corners of his thin lips. He said, "I am afraid I have been very unkind to the poor child, but I could not bring myself to burden her with the matter. Well, it seems it is beyond me to solve it, so I have presumed on our friendship to ask your advice."

"You honor me with your confidence, sir."

"Here is what happened. You may remember that one evening every month we gather for devotions in the Temple of Confucius? All the faculty wear formal dress on the occasion. Since we spend the day lecturing and teaching, we leave our formal gowns and headdresses on pegs in the anteroom of the hall in the morning and change into them just before the ceremony. Do you know the room I mean?"

Akitada nodded.

"I was in a hurry that evening, having been kept by a student, and simply tossed on my gown and hat and found my place in the hall. About halfway through the service I became aware of a rustling in my sleeve. I found a note tucked into the lining. Because it was too dark to read it there, I took it home with me."

Hirata got up and walked to one of the shelves. From a lacquer box he extracted a slip of paper and brought it to Akitada, his hand shaking a little.

Akitada unfolded the crumpled paper. The note was brief, on ordinary paper, and the handwriting was good but unremarkable. It read: "While men like you enjoy life, others do not have enough to fill their bellies. If you wish to keep your culpability a secret, pay your debts! I suggest an initial sum of 1000 cash."

Akitada looked up and said, "I gather one of your colleagues is being blackmailed."

"Thank you for that, my boy." Hirata smiled a little tremulously. "Yes. It is the only conclusion I could arrive at. I am afraid someone on the faculty has committed a serious . . . wrong, and another is extorting money in exchange for his silence. Apart from the shocking fact that two of my colleagues appear to be signally lacking in the very morals they are expected to inculcate into our students, it would be a disaster if the matter became public. The university is already in danger."

"You surprise me."

Hirata shifted uncomfortably. "Yes. We have been losing students to the private colleges, and our funds have been cut severely. A scandal could mean the closing of the university." He looked down at his clenched hands and sighed deeply. "I have spent every minute since the incident trying to think what to do. Now I have to pin my hopes on you. You are clever at solving puzzles. If you could identify the blackmailer and his victim, I might be able to deal with them in such a way that the university's reputation won't suffer."

"You may overestimate my poor abilities." Akitada spread the note out on the floor between them. "You did not recognize the handwriting?"

Hirata shook his head.

"No. I suppose not. It is not particularly distinguished. Yet the note is hardly an illiterate effort. 'Culpability' is a rather learned word. Could a student have written it?"

"I cannot say. Students never go into the anteroom. And it is true that the writing looks ordinary, but some of my colleagues are hardly great calligraphers. Besides, handwriting can be disguised."

"Yes. Hmm. One thousand cash is an impressive sum to the average person, and this is to be only the first payment. Whatever malfeasance is involved must be serious to be worth that price to the guilty man. What could be so damaging to one of your colleagues, and who could pay that much?"

The professor made a face. "I cannot imagine. It is certainly more than I can raise easily."

"What have you done so far?"

"Very little. I could hardly ask any of them if they have laid themselves open to blackmail." He passed a hand over his lined face. "It is terrible. I found myself looking at all of them with suspicious eyes and dreading every workday. Then, just when I was becoming completely distracted, I thought of you. I have known these men too long to see them with unbiased eyes. You, as an outsider, may have a clearer vision."

"But I can hardly start hanging about the university asking aimless questions."

"No, no! But there is a way. Of course you may not be able to take off the time, but we have an opening for an assistant professor of law. The incumbent, poor fellow, died three months ago, and the position has not been filled. The best part is that you would be my associate and we could meet on a regular basis without arousing suspicion. Could you take a short leave of absence and become a visiting lecturer? You would be paid, of course."

The image of his office at the ministry with its stack of bone-dry dossiers, and of the sour face of his superior, Minister Soga, flashed before Akitada's inward eye. Here was escape from the hateful archives, and an escape which promised the added incentive of a tantalizing puzzle. "Yes," he said, "provided the minister approves it."

Hirata's tired face lit up. "I think I can almost guarantee it. Oh, my dear boy, I cannot tell you how relieved I am. I was at my wits' end. If we can stop the blackmail, the university may limp along for another few generations."

Akitada gave his old friend and mentor a searching look. "You know," he said hesitantly, "that I cannot agree to suppress evidence of a crime."

Hirata looked startled. "Oh, surely . . . yes, I see what you mean. No, of course not. You are quite right. That is awkward. Still, it is better to take action to stop it. You must do as you see fit. I certainly don't know what is going on."

A brief silence fell. Akitada wondered if the professor had perhaps agreed too quickly. And had there not been the slightest emphasis on the word "know"? Finally Akitada said with a slight chuckle, "Well, I shall certainly do my best, but I am afraid that I shall be a very poor teacher. You must send me only your dullest students or our scheme will quickly come to ruin."