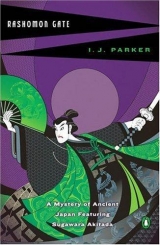

Текст книги "Rashomon Gate "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

"Yes. Mother sent someone else last time. Perhaps she gave another name. She does not want people to know she is ill."

Apparently Yakushi had no problem with pseudonyms, for the recorder merely asked, "And what name would that be?"

"Oh," cried Akitada in a tone of irritation, "how should I know? She never consults me! This is too frustrating! Let's just forget it if you cannot look it up!" He turned to leave.

"Just a moment, sir," the recorder said quickly. "There are not many requests for the Healing Buddha nowadays. Did you say a month ago? Tshk." He scanned the entries. "Here it is, the only entry in several months. The name was Kato! The Golden Light Sutra from the moment of sunrise. Tshk, tshk. Does the name ring a bell?"

"Kato," mused Akitada. "She has a cousin by that name. What day was it?"

The monk looked it up. "The ninth day of the third month."

Tora sucked in his breath, and Akitada shot him a warning glance. To the monk he said in a dubious tone, "It sounds right. What did this fellow look like?"

"Tshk. I really couldn't say, sir. Someone else made the entry."

"Well, how much did it cost last time?" Akitada asked, still frowning.

The recorder shuddered at this crude question, but said, "A generous donation of four silver bars was entered."

"Four silver bars!" cried Akitada, who did not have to pretend shock. "That does not sound right at all. My mother would never spend four bars of silver! No, I'm afraid I must have made a mistake. I shall have to consult with her before I make the arrangements. Thank you for your trouble."

The recorder sniffed and said, "Hmph, tshk. You are welcome, sir. Please hurry back!"

The young monk followed them out, looking disappointed. "Can I show the gentlemen anything else?" he asked. "Perhaps the gentleman's honorable mother might benefit from the sutra reading performed on the occasion of the archbishop's performance of the sacred rites. A very small gift to the temple would assure your mother's name would be included in the prayers."

The temple depended on such gifts for its livelihood, and the boy looked so hopeful that Akitada dug a handful of silver coins from his sash. "Will this be enough?" he asked.

The young man received the money with a smile and many bows, crying, "Oh yes, sir. Just a moment." He dashed back into the recorder's office and reappeared after a moment, carrying a receipt and announcing happily, "All is arranged, sir."

Akitada hoped that his mother would never find out. Then he remembered the fugitive Ishikawa, and asked, "Do you get many postulants your age here?"

The young monk looked surprised. "Not really, sir. Most of us come as children."

"I have an acquaintance, a very handsome and clever young man about twenty years old, who may have entered a monastery this past week. I wonder if he might have come here."

"Not this past week, sir. We have had no applicants of that age for many months now."

After they parted from their guide and got on their horses, Tora said with a grin, "You're getting pretty good at lying, sir. But who is this strange fellow? If he ordered sutra readings the same day the prince disappeared, he must be part of the plot."

Akitada decided to ignore the compliment. "Our friend Sakanoue has a weakness for impersonation. He paid four bars of silver, a considerable sum, to have the sutra chanted by a monk behind the hall at the time the prince always recited it inside." He added grimly, "It means that Sakanoue plotted the murder days before it happened. What I still do not understand is why Yoakira's friends assumed the prince was dead. How could they have known?" Suddenly he reined in his horse. "Tora," he cried, "the flies! There were flies near the image of the Buddha. Let's go back!"

With a groan, Tora followed. They returned at a canter to the shrine. Akitada rushed up the steps two at a time. When Tora caught up with him in front of the Buddha figure, his master was holding up one of the candles and tapping the carving with his fingers.

"Should you do that?" Tora asked nervously.

A fly buzzed lazily up from behind the figure's head, circled the flame, and then settled down on Buddha's nose. Akitada walked around to the back of the statue. "Come here!" he called to Tora.

Tora found him staring down at the floor. One of the dark boards had a small pale gash in it. Akitada squatted and probed with his fingers. "Give me your knife," he said.

When the blade was inserted into a crack, a section of flooring about a foot square came up, releasing a strong stench and several flies. They peered down into the dark space under the floor. It was not deep. Within arm's reach lay a box slightly smaller than the opening. Beside it was a pile of incense sticks.

"It's just storage for some sacred stuff, incense or scrolls or some such," suggested Tora.

"Neither of which would attract flies," said Akitada and reached down to lift the box. Immediately more flies rose into the air. The box had held the incense at one time. Akitada opened the lid.

"Holy heaven!" cried Tora, recoiling. "What is it?" He held his nose and slapped at angrily buzzing flies. "Some dead animal? It's crawling with maggots."

Akitada sighed. "It is a human head. The head of an elderly man with white hair," he said. "I think it used to belong to the prince." He replaced the lid and gently put the box back under the floorboards. "Sakanoue brought it here."

Tora had turned pale. "But why– and where's the rest of him?"

Akitada said nothing for a minute or so. "The driver mentioned his master's stiff robe," he finally said slowly. "It is easy to hide a man's head in such a garment. The murderer intended it to be found as proof of death, but Shinoda, who went inside with Sakanoue while the others waited outside, decided to hide it."

Akitada thought back to the day he had visited the prince's friends. Abe, clearly impaired by age, had been as confused about the events as about Akitada's name, whileYanagida had been overwhelmed with religious fervor by the miracle he had witnessed. Only Shinoda had treated the temple story rationally. In his mind, Akitada saw Shinoda again, soaking his feet in the stream, his sharp eyes gauging his visitor's purpose. He heard the old gentleman again, firmly allaying suspicions and finally warning him off sharply when he had persisted. And suddenly he understood the events of that night as if he had been present. He knew now that Shinoda had hidden the truth from him as he had hidden Yoakira's head that morning. Unlike the senile Abe, or the devout Yanagida, or the general who would not have countenanced tricking the emperor, Shinoda had both the quick intelligence and the nerve to create a miracle in order to protect his friend's memory. So that was the truth, finally, the truth inside. The head had lain here, hidden inside this hall, all along, just as the truth had lain hidden in Akitada's memory.

He sighed. "Yes. Shinoda hid the head, but he did it out of love for his friend, not to protect a killer. He certainly could not suspect Sakanoue, who had been in his plain sight the entire time. As for the body, that was left behind in one of the trunks, I suspect." Akitada rose. "Come! We have seen enough."

They rode homeward at a steady pace. Akitada was still lost in frowning thought.

After a considerable silence, Tora ventured a question. "What will you do now?"

Akitada looked at him bleakly. "I have no idea, except that I must somehow protect the boy. We are dealing with a very devious mind, and one that has carefully and quickly plotted a crime which was so extraordinary that people called it a supernatural event because there was no rational explanation for it. And because a foolish old man decided to hide the head, the only proof that Yoakira had died violently, though not at the hand of demons, the emperor himself declared the case a miracle."

"You mean, if they had left the head it would have been blamed on demons?" Tora asked. "It makes sense. People would figure the prince had done something evil. The same thing happened to a bad man years ago in the palace grounds. Everyone knows that story."

"Yes, everyone knows that story," nodded Akitada. "And Sakanoue counted on that. No doubt the incident of the soothsayer's evil omens and his curse after the prince had him whipped from his gate gave Sakanoue the idea to stage the demonic incident. Nothing more likely in popular superstition than that demons should have punished Yoakira for his disrespect. It was timely also. Yoakira had just discovered his fraud. As soon as Sakanoue had insinuated himself into the granddaughter's bed, with or without her encouragement, the prince's life was forfeit. Instead of ignominious dismissal, he saw suddenly a way to wealth and power. The prize was worth any risk."

Tora thought it over. "I understand about Lord Shinoda, sir, and I see Lord Sakanoue's motive, not that we haven't known about that for a long time now, but I don't see how he hoped to get away with it. He might've been caught at any moment."

"Not really. There were only two dangerous moments. The first one was during the impersonation, just after he left the carriage and entered the hall. He had to be quick, for though Kinsue had left again, the prince's friends would enter the courtyard any moment. I remember Kinsue talking about the amazing speed with which the prince ascended the stairs. But once inside, what Sakanoue had to do took only a moment. He lit a candle and some incense, stripped off the robe and left it, along with the bloody head, on the prayer mat. Then he slipped back out, closing the door behind him, and waited in the dark for the old gentlemen to seat themselves on the veranda. When they saw him, they were too tired from the journey and lack of sleep to wonder where he had come from. He was expected, and he was there. Soon after they all settled on the veranda, the sun rose and the chanting began. All four men on the veranda and Kinsue in the yard saw Sakanoue sitting among them while the sutra chanting was going on. Both Yanagida and Shinoda were adamant that he was there from beginning to end. He had a perfect alibi, and the world another supernatural event."

Tora shook his head in wonder. "What was the other time?"he asked.

"Sakanoue's second problem was a horse for the return trip, but that was easily accomplished while the whole monastery was running about searching for the prince. After all, horses were readily available in the stables. In fact, old Kinsue, the driver, was puzzled by the fact that Sakanoue's horse had not been one of their own."

Tora nodded reluctantly. "All right. I can see how it could be done. It was the middle of the night and they were all old men. Probably couldn't see the hand before their eyes by daylight. But tell me this: how did Sakanoue get rid of the body?"

Akitada sighed. Retracing Sakanoue's clever plot was one thing, but the body left behind in the prince's rooms, stashed headless into one of the bedding trunks, brought with it the knowledge of sudden violent death. He pictured again the room, recalled the scratches on the otherwise immaculate floor, and felt the unearthly presence of the dead man's spirit. Perhaps the murdered man had tried to tell him then. He summed up bleakly, "The corpse was taken to the country in one of the trunks."

Tora looked dumfounded. "To be unpacked?"

"No, of course not. According to Kinsue, Sakanoue drove the last cart himself, and it was night again. He probably dumped the body someplace on the road. A headless corpse is not readily identifiable."

Tora cried, "No, sir! He didn't have to do that. He passed through Rashomon! They bring their dead there at night. You could leave the chancellor himself, and nobody would think anything of it."

"Rashomon? But surely the men who pick up the dead would report a headless corpse?"

"Maybe they would and maybe they wouldn't," Tora said darkly. "Things happen to dead people in that place, and not all of them are done by the living." He shuddered, then added more cheerfully, "Congratulations, sir! You've solved the case."

Akitada nodded glumly.

"What's wrong? You got that bastard Sakanoue. I thought that's what you wanted."

"You and I may know he killed the prince, but we will never prove it. The emperor himself has put his seal on Sakanoue's safety."

They had reached the top of the ridge and caught their first glimpse of the capital spread across the vast plain below them. In the heat of the midday sun, a haze hung over the great city, and only the blue-tiled or black-thatched roofs of the imperial palaces and government halls were clearly visible. From there, Suzaku Avenue stretched southward, its willows fading in the distance as into a fog. They both looked for the tiled roofs of the distant Rashomon, but the great gate was lost somewhere in the blue vapor.

Tora cried out, "Look! There's been a fire! I thought I smelled smoke this morning." He pointed at heavy streaks of charcoal gray hanging over the northwest quadrant of the city. "I knew it would happen in this weather. Poor bastards! Thank Heaven it's a long way from home!"

Akitada thought of his family and the young boy who was their visitor. He spurred on his horse. They made the descent rapidly and were soon close enough to see the location of the disaster more clearly. The fire had been brought under control. Only a slight dark haze was left over a particular grove of trees and rooftops, while the black smoke was slowly drifting away in the blue sky.

Akitada reined in his horse with a jerk. "Merciful heaven! I hope my eyes deceive me." He pointed. "Look, Tora! Isn't that gap among the charred trees where the Hiratas' house used to stand?"

Tora came alongside, glanced at his master's white face, and shaded his eyes. "Amida!" he muttered. "It is! Let's go!"

Twenty

Charred Embers

The smell of acrid smoke greeted them blocks before they reached the Hiratas' street. It was almost palpable in their nostrils, burnt their eyes and felt greasy on their skin.

The street itself looked at first glance the same as usual. The Hiratas' garden wall stood firm, and the two willows by the gate swayed their graceful branches in the breeze. But the breeze also wafted gray filaments of smoke across the wall, and a gaggle of onlookers was gathered about the open gate.

To Akitada they seemed to peer in with the avid curiosity of people who, having been spared by disaster, savor their own luck complacently. Seized by a sudden furious hatred for them, he sent his lathered, gasping horse forward with a sharp kick to scatter them in all directions.

Inside the gate the scene was reminiscent of hell. He slid from his saddle and stood speechless, staring in horror and disbelief. Wet steaming mounds of charred rubble lay among blackened vegetation, and a bluish haze hung over the place where once the deep-gabled house with its attached pavilions had stood. Soot-darkened figures, their faces covered with wet rags, moved through the smoke like demons in search of lost souls, walking paths that had once meandered through Tamako's lush gardens.

Tamako! Akitada tried to call her name, but an icy fear made his voice falter and his tongue refuse to obey.

"You there!" shouted Tora, jumping off his horse behind him, "What happened to the family?"

One of the dark figures, a fireman, turned briefly and pointed. "Over there."

At the foot of a charred cedar there were two patches of bright color. A red-coated police constable stared down at a bundle covered by a blue and white cotton robe.

A woman's robe.

Akitada moved towards the cedar stiffly, forcing one foot in front of the other until he stood beside the constable and looked down on death.

The cotton robe had been folded back to show part of a human body. The charred remains were unrecognizable and looked surprisingly small, almost like a child's corpse. Bent double, arms and legs drawn up to the torso as if defending itself against the indignities inflicted on the dead, it was the first victim of fire Akitada had seen. That shrunken black mass of scorched flesh and bones could not be . . . but, oh, that robe!

The constable growled, "Hey! What do you think you're doing here?"

Akitada looked up dazedly. "Who is this?" he croaked.

"'Was' is the correct word," said the man lugubriously. "They dragged him out of that pile over there."

Him? Akitada looked again at the corpse and saw that the back of the blackened head still retained remnants of a gray topknot. For a moment his relief was almost too intense to contain. Belatedly, Akitada looked where the constable had pointed. The rubble was what was left of Hirata's study, a pavilion separate from the main house. Oh, God! he thought. Hirata! Not Tamako, but her father. But where was she then? His brief hope died, as his eyes searched the debris, looked past the constables for other bodies, for there had been the servants, too. Were they all dead?

Tora walked up, stared at the corpse and asked, "Where are the others? There were the professor, his daughter and two servants."

"Three more?"The constable whistled. "I just got here. I guess they haven't found them yet."

Akitada's stomach knotted. No! Oh, no! Please, not Tamako too! Not his slender, graceful girl! Only the smoking ruins of the main house and of the two other pavilions remained. Nothing could have survived under those blackened beams and the burnt thatch of the roofs. Tamako's room used to be in the pavilion farthest from her father's study. Oh, Tamako! He swallowed, gagging at the memory of that twisted black corpse under the cedar, and started towards the steaming mountain of debris, forcing his trembling legs into a run.

"Wait," cried Tora, coming after him and snatching at his arm. "You can't go in there. It's still hot."

Akitada shook him off, and vaulted onto the remnants of a veranda, then flung himself on a piece of roofing and began to tear at charred timbers and kick away sodden thatch. Before he could make much headway, strong arms seized his shoulders and pulled him back. Tora and one of the firemen shouted at him. Struggling against their grasps, Akitada finally took in their words.

"The young lady's at the neighbor's house. The servants, too."

"Tamako?" He stared stupidly at Tora. "Tamako is alive?"

Tora nodded, patting his shoulder reassuringly. "She's all right, Amida be praised! Come along, sir. We'll go see her."

Akitada swayed with the relief. Barely allowing himself to hope, he walked with Tora to the adjoining house. When he knocked, an elderly man opened and looked at them questioningly.

"M-Miss Hirata? She's here?" Akitada stammered.

The man nodded and led them into the main room of the small villa.

Though the room was full of people, Akitada saw only Tamako. She was sitting on a mat, huddled under someone's quilted robe, her skin bluish white under the streaks of soot, her eyes huge and red-rimmed from tears or smoke, and she was shaking so badly she could not speak. Looking at Akitada, she only managed a long-drawn out moan: "O . . . h!"

"I-I came," he said helplessly.

She nodded.

"Are you hurt?"

She shook her head, but tears welled over and ran down her pale cheeks.

He wished to go to her, to gather her into his arms, to hold her to himself, offering himself for what she had lost. But they were not alone. And even if they had been, she did not want him. Had never wanted him. He gave himself a mental shake. Even so, she would have to accept whatever small comforts he could provide now.

His eyes swept around the room, taking in belatedly the man's wife, a matronly lady, the Hiratas' old servant Saburo and Tamako's young maid, as well as several wide-eyed children. He asked the wife, who was hovering near Tamako, "Is she hurt?"

The woman shook her head. "It's only the shock, sir."

"Tora!" When Tora materialized at his side, Akitada said, "Bring your horse and then take Miss Hirata and her maid to our home. Tell my mother to make her comfortable."

Tamako weakly moaned some objection. The neighbor woman bristled. "Who are you, sir?"

"Sugawara," snapped Akitada, his eyes on Tamako.

"But," persisted the woman, "what are you to Miss Hirata?"

Tearing his eyes from Tamako, Akitada finally understood the woman's concern. "It's all right," he said. "Tamako and I were raised like brother and sister. Professor Hirata took me in when I was young."

The woman's eyes grew large with surprise. "Oh," she cried, "then you must be Akitada. I am so glad you came for her. She has no one else in the world."

He nodded and went to lift the drooping girl into his arms. She sobbed and buried her face against his chest as he carried her out into the street where Tora waited with the horse. Lifting her onto the saddle, he told her, "Go with Tora, my dear. I shall take care of matters here."

She looked down, lost, hopeless, defeated. He wanted to tell her not to worry, to let him take care of her from now on, but those words he could not speak. Reaching up to adjust her robe over a bare foot, he stopped. The slender foot was covered with angry red blisters. His heart contracted at the sight and he raised his eyes to hers. He wanted to ask her again how badly hurt she was, but she spoke first.

"You hurt your hand."

He did not understand at first, then snatched it back. Like her foot, his skin was bright red and blistered under the soot. Dimly aware of pain, he realized that he had burned both of his hands pulling at the debris of her pavilion. Before he could deny the discomfort, Tora lifted the frightened maid up behind her mistress, took the bridle of the horse, and led them off. Akitada stood in the street, watching Tamako's slender figure next to the sturdier one of the maid until they disappeared around the corner. For a moment nothing else mattered than that she had been spared.

But his joy was short-lived. The old servant shuffled up to stand beside him sniffling. Akitada tore his eyes from the corner and sighed. "What happened, Saburo?"

"The master must've fallen asleep over his books," the old man said, weeping. "We'd all gone to bed. It was Miss Tamako's screaming that woke me in the middle of the night. And I saw the study was all afire, and the fire was in the trees and on the roof of the main house and the kitchen. Oh! It was dreadful! The poor master. We could see him lying in the fire. I had to pull Miss Tamako back or she would've run into the flames. It was such a long time before the firemen came, and then there was not enough water in the well and not enough buckets, and now all is gone." He burst into wracking sobs. "All gone!" he cried, hugging himself, "all gone! While I was sleeping!"

Akitada touched his shoulder, lightly, because his hands were painful.

They walked back to the ruins, where Akitada spent futile hours trying to find explanations for what had happened. The professor had died, as one of the firefighters explained, because of an accidental spill of lamp oil. Seeing Akitada's disbelief, he added dispassionately that such things happened to scholars who fell asleep over their books. Saburo objected that his master had always used extreme care with fire.

Akitada wanted it to be an accident, but a black fear gnawed at his heart that it was not, and that it might have been prevented if he had spoken to Hirata sooner. Tamako had survived but she had lost everything. She had lost her father, her only support in this world. He cursed himself for the injured pride which had caused him to evade the older man for days. What if he was responsible for Hirata's death?

The twin demons of grief and shame pursued him all the way home, where he asked about Tamako and was told by his mother, unusually subdued for once, that Seimei had tended to her feet and had brewed a special tea for her and that she was now mercifully asleep. Then she completed his wretchedness by reminding him of the dismal future which lay ahead for a beautiful young woman left without a father or male relative to protect her.

The day after the tragic fire Akitada kept to his room. Seimei, who brought his food and removed it untouched, thought that his master had not moved at all, so still seemed his sitting figure, so frozen his face looking down at the folded hands, raw and red where the hot embers had seared the skin.

Lady Sugawara came, as did Akitada's sisters, but he merely listened to their entreaties and sighed. Tora brought young Sadamu, hoping to cheer up his master, and left, shaking his head.

The following day, Akitada emerged from his room, haggard and unshaven, to tend to the most urgent business and to go to Hirata's funeral.

Hirata's colleagues and his students were there, in addition to many people Akitada did not recognize. Their obvious grief added to his burden of guilt, and he shrank more and more into himself. He was intensely aware of a heavily veiled Tamako, seated behind the screens which also hid his mother and sisters. What must she think of him, who had betrayed his sacred duty to the man who had been a father to him, the "elder brother" who had forsaken them in their need, who had ignored her cry for help?

The journey to the cremation grounds, to finish what the fire had started, passed like a dream, as insubstantial as the black smoke which rose from the pyre of the man who had been more of a father to him than his own father. Afterwards he spoke to no one and returned home to disappear again into his room, where he remained for another day and night, his mind caught either in memories of the past or images of the disaster, eating nothing and drinking only water.

On the fourth day after the fire, still in the midst of his paralyzing despair, a messenger arrived from the university. He delivered a note from Bishop Sesshin, which Akitada unfolded with fingers still painful from the burns.

It said simply, "You are needed."

Outraged, Akitada tore it up and reached for a sheet of paper to write his formal resignation from the university. But something, duty perhaps or the remembered faces of his students, or the sheer pain of holding a brush, nagged at him to go in person. He called Seimei and, with his help, washed, shaved and changed into a clean gray robe.

"Please eat some of this rice gruel," Seimei said, his voice low, as if he were addressing an invalid.

Akitada ignored him and left.

When he walked into the main hall of the school of law, he found it filled with students, Hirata's and his own. Only young Lord Minamoto, still residing at Akitada's house for the sake of his safety, was absent. The students sat gathered in a semicircle around the large figure of Sesshin. The bishop wore a gray robe with a black and white stole to signify his mourning. The students were in their usual dark gowns, but their faces were sad and many eyes were red from weeping.

"Welcome, my young friend," Sesshin greeted him, his voice rumbling. "We have been waiting for you. The students have talked to me about their memories of Professor Hirata, and I have told them that you were one of his special students once. Perhaps you will share some of your memories with us?"

Akitada glared at him. It was a dreadful request!

Cursing Sesshin in his heart, Akitada turned to the students. Ushimatsu was leaning forward slightly, his plain face filled with pity. Akitada looked at the others, wondering if his grief was so transparent to them all. There was Nagai, poor ugly Nagai, his eyes swollen with weeping and his mouth blubbering– at his age! He had not been this distraught in prison with a murder charge hanging over his head! But then Hirata had loved Nagai– like a son almost. Perhaps, not having had a son of his own, he had let his students fill that void. A new wave of misery washed over him. Hirata had loved them all, Akitada included! Tears dimmed the faces before him. He swallowed and tried to speak, but his throat closed up, leaving him mute. He made a helpless gesture to Sesshin, but the fat monk placidly nodded encouragement, pointing to a cushion by his side.

Akitada sat and somehow he found his voice, though later he could not recall what he had told the students. In a way, he had carried on a dialogue with himself about his life with Hirata. It had been a strangely purging experience, and he had wept. But he had found a measure of peace.

When he stopped, there was a long period of silence. Then Sesshin began to recite the soothing words of the Pure Land sutra. He closed by saying, "There is a difficult meditation practice in our religion, in which we submerge ourselves completely in nothingness. Only a few achieve success. But when we are successful, the mind is calm as the sea. Passion, hatred, delusion and sorrow fall away. False thoughts vanish completely. There are no pressures. We issue forth from our bonds and separate ourselves from all hindrances and cut off the foundations of our suffering. This is called entering Nirvana. It is a state of blessedness which can be achieved completely only through death. And it is where our dear friend now dwells forever."

There was the sound of soft sighs from the students, and then Sesshin arose, nodded to the students and to Akitada and walked out.

Akitada got up dazedly and followed. The old monk was waiting on the veranda, his hands on the railings and his eyes fixed on the roofs of the distant city. He did not turn as Akitada joined him.

"So many deaths," he said with a sigh, "in the midst of so much life." He gestured at the teeming city before them and back towards the lecture hall filled with quietly talking students. "I am forever reminded of the eight unavoidable sufferings: birth, old age, pain, one's own death, the death of a loved one, evil people, frustrated desire and lust. Sometimes I think I have had more than my share of all but one of them. Why are you so angry with me, my friend?"

"Your Reverence," Akitada said awkwardly, "I apologize for my unpardonable rudeness to you."

Sesshin's dark, liquid eyes passed over Akitada's face. "Never mind! I have been more foolish than you, and it is I who am in your debt. You opened your heart and home to a lonely child. Tell him from me to keep up with his studies."