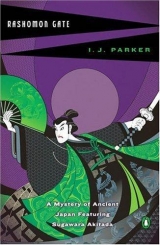

Текст книги "Rashomon Gate "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

"Not at the moment."

"Good!"The little lord rose. "In that case, you will be able to start investigating Sakanoue immediately. Remember the reward." He gave Akitada the tiniest of bows and was gone.

Akitada sat looking after him and laughed softly. Reward indeed! Young Lord Minamoto certainly knew how to put on the airs of the great man accustomed to giving orders. Still, the boy's awareness of his obligations was quite admirable and he had displayed considerable courage in his defiance of Sakanoue. On the whole, he thought, the young man showed much promise.

It was too late to go home, so he sent a servant to the staff kitchen for his noon rice and ate it alone in his room. When he was done, Hirata came in. Akitada saw with concern that the older man looked very tired and drawn again.

"How are you feeling today?" Akitada asked. "You gave me a scare yesterday."

"It was nothing. I am quite well again. Indigestion is one of the infirmities of old age. The reason I stopped in was to tell you that Sesshin has called a meeting. We had better be on our way."

Akitada was momentarily at a loss. "Sesshin?"

"The abbot of the Pure Water temple, but more importantly the director of the university. He is also our professor of Buddhism, a function he does not often carry out, because he prefers to live in his mountain villa which he intends to convert into a temple. He arrived about an hour ago; Oe's murder brought him back. No doubt he will disappear again as soon as he has appointed Oe's replacement."

"Hardly a testimonial of his devotion to the institution," said Akitada sarcastically, getting up and adjusting his hat and robe. Even at the best of times he had little respect for Buddhist clergy, and this one seemed lazier than most. "Isn't Ono back? Won't he take over for Oe?"

Hirata shook his head dubiously. "I have no idea. Ono has hoped for just this chance for a long time. I think it is the only reason he put up with Oe's abuse. But he is not the man Oe was, and Sesshin knows this."

They walked across the grounds to the Buddhist temple, discussing the effects of murder on their fixed routines. At one point, Akitada said, "Oh, young Minamoto spoke to me earlier. He has asked me to look into the matter of his grandfather's disappearance. He believes the prince was murdered by Sakanoue."

Hirata was so astonished he stopped in his tracks. "Lord Sakanoue? Oh, Akitada, please do not get involved in what is surely a mere child's fantasy. They say Sakanoue may become the next prime minister. If you let it be known that you support the boy in his charges, you will put yourself in jeopardy. You must speak to Sesshin about this."

Akitada laughed. "Speak to a monk? He is just about the last person I would consult."

Hirata shook his head impatiently. "I know all about your distaste for the religion, but in this case you cannot be aware of who Sesshin really is. He is another son of the Murakami emperor and the late Prince Yoakira's half brother. That makes him the boy's great-uncle."

Akitada's jaw dropped. He had assumed the boy had no male relatives left. "Sesshin is Sadamu's great-uncle?" he asked. "How could this man turn his back on the children? What sort of man is he?"

Hirata started walking briskly. "Come," he said. "That you must find out for yourself."

Crossing the street, they entered the temple courtyard. The doors of the small main hall stood wide open. Someone looked out and beckoned. They hurried in.

Akitada had forgotten how pretty the small temple was. It looked deceptively plain with its square, red-lacquered columns against the dark wood of ceiling and walls. Its only ornamentation was a lovely carved frieze of cranes, painted black and white with brilliant red patches on their heads. Behind the raised dais with its single cushion, covered in the imperial purple silk, hung five large scroll paintings of Buddhist deities. Before each scroll stood an elegant black-lacquered table with silver ceremonial implements.

Most of the others had already arrived and stood around chatting. In fact, apparently only the august personage himself was missing, for even the elusive Fujiwara and Ono had returned.

They greeted Ono first. Akitada had not expected grief, but the man looked both excited and smug. Akitada wondered if he had been confirmed as Oe's successor. They exchanged the conventional expressions of regret over Oe's death. Ono did not bother to explain his absence, and there was little point in pursuing the matter. Hirata turned to speak to someone else, but Akitada said, "You must be overwhelmed with duties. Will you rely on Ishikawa to give you a hand? I have not seen him since the poetry contest."

"I have no intention of employing that fellow," Ono said sharply. "He may know his Chinese, but his manners are unacceptable and he is completely unreliable. Would you believe it, he has taken off without so much as a note explaining where he went or when he planned to return?"

"I dare say Kobe will dig him up," said Akitada, and regretted his choice of words immediately. "You and Ishikawa were the last to see Oe alive that night, weren't you?"

Ono's eyes shifted nervously. "We only took him as far as Mibu Road. He insisted he had private business to take care of and ordered us to return to the competition to keep an eye on things."

"I see." Akitada decided to probe further. "I don't recall seeing either of you return."

Ono stiffened and glared at him. "I cannot speak for Ishikawa," he said coldly, "and I certainly don't feel I need to explain my actions to you, but I was quite unwell and had no desire to disgrace myself before the company, so I remained around the corner near the side stairs." Narrowing his eyes, he added, "For that matter, I saw you leave early, before the last competition started."

"My apologies." Akitada bowed. "I spoke thoughtlessly."

Ono acknowledged this with a curt nod. Akitada walked away, reflecting that the erstwhile worm was putting on the scales of the dragon already. Or had Ono always been a poisonous snake masquerading as a harmless creature?

He looked around and joined Nishioka, who was talking to Fujiwara. The latter seemed to have lost his booming good humor and merely looked tired and irritated.

But Nishioka's eyes sparkled. He was more cheerful than anyone else here. Tucking some loose strands of hair back into his topknot and scratching his lantern chin, he said to Akitada, "I was just telling our friend here that he need not worry about being arrested for Oe's death. I have thought about it and decided that his particular personality disqualifies him from all but the most brutal of murders, and then only if he were provoked upon the instant and carried out the deed without regard to his own safety."

"Thank you for that testimonial," said Fujiwara dryly. His cheek showed the ugly marks left by Oe's nails, and he had not bothered to change. Akitada noticed the blood stains on the sleeve of his robe and wondered if he only owned the one garment. "But," continued Fujiwara, "how will you convince the police captain that I did not have another quarrel with the man in the Temple of Confucius and lost my temper?"

Nishioka shook his head. "Impossible! You would not have bothered to tie him to the statue. You would have smashed a few things and run off to get drunk."

Fujiwara choked back a laugh. "I see my reputation is well established. Well, who, in your opinion, has the correct personality?"

"Oh, at least two people." Nishioka smiled slyly. "Though in one case I have not yet worked out how it was done unless he had an—" He broke off as a sudden hush fell in the hall.

A side door had opened and His Reverence entered. The noble monk was hardly a prepossessing figure. Very fat, he was dressed in a black silk clerical robe; a green and gold embroidered stole was slung across one shoulder and his paunch. He padded with a waddling gait to the raised dais and plopped down on the cushion with a grunt.

They all bowed deeply. Akitada risked a surreptitious look and saw a moon face with small deep-set eyes under heavy lids and a small, soft mouth. Sesshin surveyed the bowed backs impassively. To Akitada there was a sort of naked grossness about the man which was not entirely due to his shaven head. His smooth, round face had hardly any eyebrows and rested on a triple chin. The ears were enormous, with pendulous lobes which rested on fleshy shoulders.

Perhaps it was due to his natural and learned dislike for Buddhist clergy, but it seemed to Akitada that appointing a man such as this as president of the university, a spoiled member of the imperial family who had renounced his worldly career in order to devote himself to leisure and luxurious living, was another example of the weakness of the current government.

The fat monk cleared his throat and said in a soft, dry voice, "Thank you all for coming. Please be seated. "With a general shuffling of feet and rustling of robes they obeyed.

Sesshin looked over their heads and spoke in the same low, soft voice. "Recent events require my presence here and I take this opportunity to make a few announcements." The silence in the hall was profound as they all strained to hear. Akitada thought irritatedly that the man was even too lazy to raise his voice. "Because of the unfortunate death of our colleague, certain disruptions of my routine and yours are unavoidable, but we must attempt to carry on. You will, of course, meet your students as usual and cooperate fully with the police. Ono will temporarily see to the lectures on Chinese literature. I will send him a suitable assistant. As usual, when I am in residence, I will conduct a series of lectures on the scriptures. This time I will give a commentary on the Great Wisdom sutra. It will take place every afternoon immediately after the noon rice. You may announce this to your students. That is all." He nodded to them, rose with another grunt, and padded out.

That was all? For a moment Akitada sat stunned, while his colleagues got up and began to chatter. Then cold and irrational fury seized him. How dare the man? Before he was fully conscious of what he was doing, he was up and striding after the figure of the priest.

He passed through the door into a long dark corridor where the distant faint daylight gleamed on polished black boards. Ahead of him moved the large figure of the monk. Sesshin stopped at a door, disappeared into the room behind, and closed the door after him. Akitada opened it again and walked in.

"I want to speak to you," he snapped, adding lamely, "Your Reverence."

Sesshin had his back to him and was removing his stole. Turning slowly, he looked at Akitada. After a long moment he said, "You must be Sugawara. If I remember, abruptness was always a failing of the Sugawaras. Please be seated."

Akitada was still fuming. This man had deserted two helpless children. "What I have to say will not take long. I have just been told that you are the brother of the late Prince Yoakira."

Sesshin calmly folded the embroidered stole and draped it over a stand. The room contained little more than that, a pair of cushions and a small low table upon which were set a wooden rosary, a beautifully decorated sutra box and a brazier with a teapot. The monk lowered himself to the cushion next to it. "Forgive me for sitting down myself. I am an old man. I would offer you a cup of tea, but it is not customarily consumed while standing. You young fellows do not allow yourself enough leisure. All is haste and intensity for you."

"I am afraid that most of us do not have the privilege," Akitada said tartly. "I apologize for the abrupt intrusion, but I won't keep you from your leisure long. Your great-nephew, Lord Minamoto Sadamu, is presently a student here, and I had occasion to speak to him at some length this morning about a situation which is disturbing, to say the least."

Sesshin remarked placidly, "I hope the young scamp has not given you cause to complain of him?"

Akitada steadied his breath. "Not at all. Quite the opposite. He is extremely bright and has a sense of responsibility beyond his years. That is why I have acceded to his wish to investigate his grandfather's death."

Sesshin sighed and reached for his beads. He neither responded nor changed his calm demeanor. If anything, he seemed more indifferent than before. The heavy lids drooped over his deep-set eyes until he looked almost asleep.

"Have you nothing to say?" cried Akitada. "I had hoped that you would take an interest in your brother's grandchildren. They are quite alone in the world and, if I am not mistaken, in danger of their very lives."

There was no reaction from the monk, and Akitada turned to leave. "I am sorry," he said. "I was mistaken."

"A moment," said the soft dry voice. Akitada paused with his hand on the door latch and looked back over his shoulder. The smoldering black eyes were fully on him now. "You intrude most painfully into my hard-won peace," he said. "When I lost my brother, I nearly lost myself. My faith wavered and my very soul was drowning in tears. I returned to the world to conduct the memorial service, and was told on that occasion that the children were in good hands, that they had chosen their future paths freely. After the service I returned to the mountains to ask the Buddha's help in emptying my heart and mind of the memories. I do not tell you this because I owe you an explanation, but because I am grateful that my great-nephew has found a friend in his teacher. Now you may go in peace."

Akitada wished to argue but knew it would be both futile and dangerous to do so. He bit his lip, bowed, and left.

Fourteen

Gate of Death

Since Lady Sugawara decided it was time for the annual cleaning of the family storehouse, Tora could not leave for the city until late in the day. When he was finally free to look for the old beggar, he headed first to the office of the eastern capital near the university.

Tora stated his business at the gate, and the guard became excited. "Hey, fellows!" he shouted. "Here's someone asking about old Umakai."

Guards, constables, and clerks gathered around them. All expressed concern about the old beggar. Umakai was their special pet, and they had missed him. He was expected regularly for his noon rice. This the guards and clerks provided by passing his bowl around for everyone to contribute a small share of his own meal until the old man's bowl was filled to overflowing. The trouble was he had not been seen, except for a brief visit right after his release from jail, and they were all worried.

Tora asked if Umakai might be eating elsewhere, for instance with their colleagues in the western office, but they assured him that those people had hearts of stone and arrested beggars as vagrants and loiterers. In short, nobody knew where Umakai might have disappeared to.

Tora thanked them, promising to keep them informed. He began walking through increasingly busy streets, stopping from time to time to ask peddlers and street musicians about the old man. Some knew Umakai, but none had seen him around lately. It was not until he neared the market that Tora picked up a clue, and when he did, the news was not good.

He saw a middle-aged prostitute who was plying her trade on the street. No longer attractive enough to work in the Willow Quarter, she was reduced to accosting passing laborers and apprentices. Her eyes had assessed Tora, but his neat blue robe and black cap had convinced her that he was beyond her reach. Tora approached her. A woman like this would be familiar with the other street people who competed with her for a few coppers.

She was disappointed when he asked his question, but told him she did not know Umakai. When Tora turned away, she cried after him, "They fished an old man out of a canal this morning."

Tora's heart sank. "How do you know?"

"I was there, wasn't I? Bunch of people were looking, so I went to see what was up. He was dead all right. Small, skinny old guy. Looked down on his luck. Some old drunk, maybe. Stumbled into the water and drowned. Guess the warden thought so too. He just looked at him and then let his friends take him away. Could be it's your guy."

Tora nodded. "It could be. These friends? Do you know where I might find them?"

She laughed. "They're poor folk, like me. We don't have a regular place to go home to like you." She gave Tora's neat outfit an envious glance. "People like us live and sleep in the streets, or maybe in the western city in some shed or old ruin. But mostly we keep moving." She eyed Tora speculatively. "I don't suppose you'd be interested in a bit of pleasure?"

"Another time. I'm on duty."

She nodded in resignation and turned away.

"Wait! If you can describe the men who took the body away, there's ten coppers in it for you."

"Ten coppers?" She flushed with pleasure. "I can do better than that! It was Spike and Nail got the dead guy. Spike's a big brute. He lost a hand and put a metal spike in its place. His buddy's a thin little feller. Get it? Spike and Nail! Heh, heh. Anyway, I guess they knew what they'd find, 'cause they'd brought along a monk to say a few prayers."

Tora stared at her. The story sounded weird, but there might be something in it. "Thanks," he said and counted the promised coppers into her dirty hand.

She looked at the money, then closed her fingers tightly around it. Nodding towards a dirty alley behind her, she offered, "If you like, I could twirl your stem for you." She grinned and passed an agile tongue across her lips. "It won't cost you nothing."

Tora blushed. "No, thank you. I'm in a hurry to find out what happened to the old man." He turned to walk away.

"Bet they took him to Rashomon," she called after him.

Rashomon!

Tora shuddered. Of course. Everyone knew that the poor who could not afford a funeral left their corpses there for the authorities to gather and cremate on a common pyre. That was why nobody but cutthroats went to Rashomon after dark– and the light was fading rapidly.

Actually Rashomon was the great southern gateway of the capital. An impressive two-storied structure with immense red columns, blue tile roofs, and whitewashed plaster walls, it had been built as a fitting welcome for visitors to the imperial capital. As soon as they passed through its massive structure, they saw before them Suzaku Avenue, immensely wide and long, bisected by water and lined with willows, leading straight as an arrow to Suzakumon in the far distance, the entrance to the imperial city itself. And if you were leaving the capital, you walked through Rashomon and found yourself on the great southern highway which led to Kyushu and exotic foreign ports.

But Rashomon had fallen on hard times as, indeed, had the capital itself. The gate was rarely guarded nowadays and had become a hangout for vagrants, crooks and undesirables from the surrounding provinces. After dark, ordinary people avoided the place, making it a safe haven for criminals. The police turned a blind eye, except that twice a week, in the pre-dawn hours, the city authorities sent crews to gather the corpses.

Tora dreaded a visit to the upper floor of Rashomon, where bodies were generally left, about as much as an interview with the king of hell himself, but the prostitute's story had to be checked out and his master expected results. It was not the first time since he had entered Akitada's service that Tora had faced what he feared most, the supernatural.

In this case his immediate decision was to postpone the inevitable. He went to the umbrella maker's house first. Omaki's father was in. Hishiya was in his late fifties, thin, balding and prematurely bent, with the gnarled and scarred hands of his profession. He smiled and bowed deeply, expressing his gratitude for Tora's interest in his poor daughter. To his further credit, in Tora's eyes, he made no mention of blood money. Unfortunately he seemed to know nothing of his daughter's friends.

When patient probing had produced no more than protestations of shock and puzzlement, Tora exclaimed in frustration, "But you're her father! How could you not care that she slept with men or who the father of her unborn child was?"

The elderly man bowed his head. "Omaki was a good girl, but we are very poor. She tried hard to make a living playing the lute. She was very talented; all who heard her said so. But the men where she entertained, well, they want more than a bit a music, and she had no one to look out for her. Who am I to ask questions or to blame her, when I am too poor to give her a dowry?"

"Sorry," mumbled Tora. "The trouble is, from all we hear, she was pleased about the kid. Like she expected to marry its father."

The man sighed. "Maybe. I wouldn't know. I'm gone so much, selling my umbrellas in the market and gathering bamboo for more. You'll have to ask my wife. Women have their secrets. Only she's not in right now."

Tora rose. "Never mind! It doesn't matter. I'll ask around."

He spent the next few hours in the amusement quarter. His day had been long and Lady Sugawara had worked him hard. He felt in need of a rest and liquid refreshment. Besides, the bright lights and sounds of laughter and music blotted out thoughts of the horrors awaiting him in Rashomon.

He drank liberally and asked his questions without getting any helpful answers. Omaki had not been well liked by the other women in the quarter. They thought her proud and secretive, and none of them knew anything of her private life. At some point the combined effects of his exertions and the wine caused him to nod off. When the waiter shook him awake, wanting his place for other customers, it was past the middle of the night, and Tora had no reason to put off the unpleasant business of Rashomon any longer. He reflected bitterly that murder investigations exposed a man to danger not only from killers, but also from the angry spirits of their victims. Rashomon, being a receptacle of the unwanted dead, must be teeming with disgruntled specters.

Casting an uneasy glance at the sky, he saw that it was clouding up, and the moon made only fitful appearances. The cool, clear days of spring were over. Soon it would be hot and the rainy season would start, but not quite yet. It was merely dark, an excellent night to search for abandoned bodies and encounter gruesome ghosts. It suddenly occurred to Tora that he was totally unprepared for this undertaking and he headed for the market.

Most vendors had closed down, but he found a cheap lantern and then searched with increasing desperation for a soothsayer. He found this most essential individual in the form of a shrivelled old man who had fallen asleep over his stock of divining sticks, patent medicines and amulets.

"Wake up, Master," said Tora, shaking him gently by the shoulder. It did not do to offend one familiar with demons and spells.

"What do you want?" quavered the old one.

Tora explained his errand, and the old man nodded. "Wise precaution," he muttered, searching through his basket. "Last man went there after dark met a hungry ghost and had to give up his whole right arm to get away."

Tora shuddered.

The old man produced a wooden tablet with the crudely drawn image of the god Fudo. He threaded a string through its hole and knotted it. Next to this he laid a handful of rice. Finally he fished a sheet of cheap paper with some poorly written lines from the breast of his patched cotton robe and added this to the other two items. "Fifty coppers," he announced.

Tora blanched. He felt in his sleeve. "Do I need all that?" he asked.

The old man sighed. "The amulet you hold up before you if you encounter a demon. Fudo will strike the demon for you. The rice is to toss into a room before you enter; it drives hungry ghosts away. The paper contains the magical incantation of the virtues of Sonsho, who's Buddha's incarnation and protector against malevolent spirits. When you recite it, you will be safe even in Rashomon."

"I can't read," confessed Tora.

The old man sighed again. Taking the paper back, he said, "I'll read it; you repeat it."

The incantation was long and referred to some peculiar Indian names and terms, but Tora tried. The old man corrected him, sighed, corrected again, sighed, and finally nodded. "You got it! Practice it on the way."

"How much without the paper?" asked Tora.

The old man glared at him. "Fifty coppers," he said. "I should charge extra for the instruction!"

Tora bowed, mumbling his thanks for the generous price, turned over all but five coppers of his month's salary, and proceeded, only slightly fortified in mind, to Rashomon.

When his lagging steps finally brought him to the great gate, he found it nearly deserted. Only the hardiest, the most foolish or the most desperate of souls remained here after dark. A couple of beggars sat on the steps, hoping against hope for some late travellers entering or leaving the city. Inside, under the roofs of the vast structure, a few vagrants had taken shelter for the night. Tora surveyed them carefully.

An elderly couple in rags huddled against the base of a pillar, asleep and snoring. Near them an itinerant monk leaned against the wall, his straw hat covering his face, and his staff and bowl lying by his side. Monks of this type were a familiar sight on highways. They were not attached to any particular monastery and spent their lives travelling. This monk looked to be strong and healthy; at least he had muscular legs and large feet. Vagrant monks could be very unpleasant adversaries. Too often, they were wanted criminals in disguise. Tora watched him carefully, but decided that he, too, was fast asleep.

The sound of voices and laughter drew Tora to the other side of the gate. There, on the steps leading down to the highway, sat a group of men, engaged in a game of dice by lantern light. They looked like common laborers, their short-sleeved cotton shirts tucked into loose cotton trousers and their heads covered with knotted pieces of cloth. All chattered happily until one of them looked up and saw Tora in his neat blue robe and black cap. "An inspector!" he cried, and they all scrambled up and dispersed.

Tora chuckled. He had been mistaken before for one of the city officials who checked up on travellers. Since none of the men had fit the street woman's description of Spike or Nail, he would have to find the body himself. Tora turned back to enter the interior of Rashomon.

That was when he first noticed the armed man. He sat just inside the doorway leading into the building. His arms rested on his knees, and he had laid his head on them and gone to sleep. A big, brawny fellow, he had a sword slung over one shoulder and a bow and quiver of arrows over the other. Tora recognized the type. They were soldiers who served no master, but travelled from town to town looking for work which required the use of their weapons. If no such work was available, some became highway men, lying in wait for wealthy and unarmed travellers. This one was cautious enough not to take off his weapons even while he slept.

Suddenly, as if he felt Tora's scrutiny, the man raised his head slowly and looked at him. He was still young, about Tora's age, with a neatly trimmed beard and mustache, and cold steady eyes. They exchanged measuring looks. The armed man looked away first, spitting and scratching his topknot in a gesture of contempt.

Tora wished he had worn his old clothes and decided it was safer to avoid the armed man. He took the door on the opposite side instead.

It led into a large but empty guard room. Briefly, weak moonlight came through the door and a window, but a cloud extinguished even this. Tora lit his lantern; by its light he could barely make out the wooden stairs which ascended into the blackness of the second floor. A pervasive smell of dirt, rotten food, sweaty rags and, faintly, of decomposing flesh, hung in the dry, still air. From upstairs came soft rustling sounds. Hungry rats or angry spirits?

Tora shivered and touched the amulet tied around his neck. Murmuring a line from his protective spell, he started up the stairs slowly. When he was halfway up, a faint, flickering light appeared above, shifting weirdly across the dark beamed ceiling. A peculiar humming sound accompanied the light. Tora paused, feeling for the grains of rice in his sash. Suddenly a gigantic, grotesque shadow moved across the ceiling of the floor above. It belonged to a monstrous creature, misshapen and hunchbacked, with a clawlike hand that reached across the entire space, withdrew, and reappeared with a huge knife in it. Every hair on his head bristling, Tora tried to recite his spell, but his mind had become a complete blank. He tried to throw the rice, but spilled it on the steps. Then the knife above slashed downward, and Tora jerked back. Feet slipping on the spilled rice, he crashed down the stairway with a great clatter.

Above a woman's voice cursed loudly and with gusto.

Heaving a sigh of relief, Tora picked himself up. He could deal with low class females of the living variety. He rushed up the steps. When he reached the top, the light went out. At the same moment, a draft caught the candle in his own lantern, and all became dark.

Tora took a couple of steps forward into utter blackness and stumbled over a bundle, nearly falling flat on his face.

An eerie cackle from somewhere near his knee assailed his ears, and he smelled the stench of rotting gums. Whoever it was, he or she was right beside him. Tora moved aside quickly and promptly stepped on something soft and squishy. The cackle turned into a warning screech.

"Here! Watch what you're doin'! She won't holler, but you near put your big foot on me!"

"Sorry!"

He found his flint and relit his lantern. In its light, an old crone peered up at Tora. She was dressed in many layers of filthy rags, her long white hair draped crazily over hunched shoulders. In this light, her face looked like an animated skull. Gray skin clung to sharp bones, eyes disappeared in dark hollows, and a toothless mouth gaped in the rictus of a grin. She was cowering near the corpse of a naked female. Tora retreated with a curse when he realized that he had just stepped on the dead woman's arm.