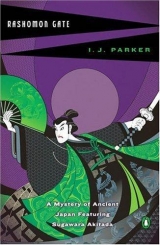

Текст книги "Rashomon Gate "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Akitada was touched. "Thank you both," he said, and turned to the boy. "Sadamu, I believe you have met Tamako, haven't you?"

"Oh, yes," grinned the boy. "I quite approve, you know."

Sesshin chuckled, and Akitada said, "I am deeply gratified."

The boy nodded solemnly. "She was very nice to me," he said. "We talked about death, my grandfather's and her father's. What she said made me feel much better. I think she has much wisdom for a woman."

"Ahem!" Sesshin cleared his throat again.

This time the boy blushed. "I beg your pardon," he murmured. Reaching for a small, beautifully decorated lacquer box which rested beside him, he pushed it across to Akitada. "It is the reward you have earned," he said and then glanced at Sesshin, who gave an encouraging nod. Sitting up a bit straighter, Sadamu looked earnestly at Akitada and announced, "Your loyalty to me and my family in our distress and your cleverness in seeing through Lord Sakanoue's plot have put me and my family deeply into your debt. I wish to make formal acknowledgment of the great service you have done. The Minamotos will be forever in your debt, and I shall see to it that the fact is recorded for posterity." He bowed with great dignity.

Akitada did not know what to say, so he also bowed deeply. "Thank you, my lord. I am deeply honored by your words, and shall treasure your gift."

The boy gave a sigh of relief and smiled. Then he reached into his sleeve and pulled out a small narrow object, wrapped lopsidedly but with great care in a square of brocade and tied with a gold cord. This he handed to Akitada, saying, "Please accept this worthless trifle on my own behalf."

Akitada was deeply touched. He said with a smile, "There was no need whatsoever for all this, Sadamu. I was merely lucky." He looked down at the small package dubiously.

"Well, open it!" the boy cried.

Akitada undid the many knots with some difficulty and unrolled the beautiful piece of fabric to reveal a flute. It was a lovely instrument, old and clearly made by a fine craftsman, though it was quite plain. He looked up in delighted astonishment. "A flute?"

The boy's face was alight with pleasure. "Do you like it? Is it the right thing? You told me once that you wished you could learn to play the flute, do you remember? Well, now you can!"

"Oh, my dear young friend, it is the most perfect present," cried Akitada, fingering the instrument and wishing he could try it out. "I had forgotten, but you are quite right. It will give me enormous pleasure. Thank you very much." He was tempted to raise it to his lips then and there, but confined himself to admiring its workmanship. Finally he put it back into its wrapping and placed it aside. "I trust you are comfortably settled by now?" he asked.

"Oh, yes." The boy exchanged a glance with the bishop, and explained, "My great-uncle is to be my guardian until I come of age. He has taken up his residence in our mansion to be near me and supervise my studies. But His Majesty has graciously confirmed me as head of my clan, so I have a great deal of work to do every day before I can get to my books."

"Ah," said Akitada, bowing deeply to him, "then I am indeed honored by your visit, my lord." This boy had suddenly become a very rich and powerful man. He recalled the youngster's sense of responsibility for his people and was glad.

Sesshin chuckled. "He is young, but he shows promise," he said, deflating the boy's pride a little. Then his face abruptly turned serious. "We have also some other news and a confidence to share with you. I followed your suggestions about Rashomon and, finding by good fortune a poor woman who had some information, was able to locate my brother's remains. They have been put to rest very quietly on his ancestral estate in the country."

Akitada glanced at the boy who met his eyes calmly. "I am very sorry for what happened to your grandfather," he told him. "It must be just about time for the forty-nine days to be up. I hope his spirit is at rest now."

The young lord nodded. "Yesterday," he said, his voice catching a little, "we held a service in the mansion. It was just for the family and a few servants. I was afraid that you were still too ill to attend. Kinsue and his wife, you know, were terribly worried about grandfather's spirit not finding a path into the next life when the waiting period was up. They seemed much relieved. Afterwards Kinsue took me to the old tree in grandfather's courtyard and showed me that it had put forth new leaves. He said it was a sign that grandfather has entered his new life."

Akitada thought that it was more likely that the rain had saved the old tree, but he felt again that slight shiver at the back of his neck, as if a cold finger had barely brushed his skin.

Sesshin cleared his throat. "We wish to take you into our confidence on the matter of the miracle," he said. "When I informed His Majesty about our suspicions, he immediately consulted with the chancellor and his closest advisers, and it was considered best not to destroy the people's faith in the Buddha or the reputation of the temple. Sadamu and I concur completely with His Majesty's decision."

Akitada bowed. "The wisdom of our august ruler is inspiring. You honor me with this confidence."

The bishop nodded. "I have also had some news of Lord Sakanoue. His Majesty has seen fit to appoint him 'Subduing Rebels Official' and has dispatched him to the northern frontier. There has been some particularly fierce fighting there lately. Lord Sakanoue has expressed his gratitude for being allowed to die for his country."

"Pah," said the boy. "He's a coward."

Sesshin frowned and moved smoothly to a discussion of general conditions in the north country. Akitada listened politely, wondering how long the bishop would dwell on the subject.

"The chancellor was mentioning to me just the other day that it is nearly impossible to keep good officials for any length in provinces like Noto, Echigo, Iwashiro and Uzen," he said, looking earnestly at Akitada. "The distance from the capital, the cold, the troubles with the local aristocracy all seem to drive the appointed governors and other officials to absent themselves from their headquarters for long periods of time."

More puzzled than ever, Akitada tried to look interested.

"Echigo, for example, has been without a resident governor for a number of years. Can you imagine? No senior official at all to represent the government?"

"None at all?" Akitada's real concern was stirred. He recalled vividly the problems which even a good governor had encountered in Kazusa, a province which was not nearly as far from the capital as Echigo. "Could not His Majesty replace inadequate administrators with more suitable persons? Echigo is a rich province. To leave such a significant source of income for the nation to the mercies of local interests seems a dangerous policy." He gulped. "I beg your pardon. I did not mean to criticize His Majesty, of course. Only there must be any number of good people who would gladly undertake such an assignment. The challenge alone must outweigh the lack of comforts, and the distance from the capital is easily balanced by seeing new places and learning new things. I remember when I was sent to Kazusa some of my friends thought this a punitive assignment, but I was jubilant . . . ." Akitada broke off in some confusion. When no one commented, he flushed with embarrassment. "I beg your pardon, Your Reverence," he murmured.

He risked a glance at Sesshin's face. The old monk was smiling benignly and nodding his head. "I am very glad to hear you say so. It is understandable that His Majesty's august rule should not always be understood by the people in distant places where the civilizing forces of the capital can only be transmitted by His Majesty's appointed representatives. Sadly, unlike you, too few of our young men are willing to accept such assignments, even if they have a more enlightened idea of the conditions there than their elders."

Akitada's heart had started beating more rapidly. Surely Sesshin was speaking in a very pointed manner. He glanced at the boy and saw that he was watching him expectantly. Looking back at Sesshin, Akitada said, "I am certain the emperor can find many able persons eager to exchange the stodgy routine of their duties in one of the bureaus and ministries for the excitement of travel and the freedom to improve conditions in one of our provinces."

"Ah," said Sesshin, smiling more widely and nodding. "Perhaps one or two. At any rate, that is what I told the chancellor when he expressed his worries about affairs in Echigo." He glanced out at the cloudy sky. "But the rain is letting up and we must not keep you any longer. It was a very pleasant visit. Please compliment your servant on the excellent tea and cakes."

His heart still pounding exultantly, Akitada expressed his gratitude for the visit, the box and the flute and, inwardly, the glorious new hope he hardly dared to acknowledge to himself. He accompanied his illustrious visitors to their carriage and watched them leave in a bemused trance.

Back in his room, he bent to pick up the box and flute to place them on a shelf. The box seemed astonishingly heavy. He opened it and saw with consternation that it was filled with gold bars. His reward, the boy had said. There must be more than three years worth of salary here, enough to mend the roof and pay the wages and costs of his newly increased household, and still leave something in reserve.

Filled with the joy of it, he went to tell his wife. But the little maid informed him that her mistress had gone to her former home as soon as the rain had eased a little. Akitada felt a sudden concern for her safety and peace of mind and decided to follow her.

The sky was clearing partially, and he risked going without his straw raincoat. Walking as quickly as the many steaming puddles permitted, he crossed the town, worried how he would find her on this, her first visit to the place of the tragedy which had taken both her father and her childhood home from her.

Although he had sent workers to clear away the large debris, the grounds looked dismal after the rain. There was bare black mud where the house had once stood, and charred trees clawed with naked, twisted fingers towards the skies. All the lush flowers and shrubs had shrivelled into sodden clumps of brown decay. Tamako's garden had died as surely as had her father and her past life.

She stood, huddled in a straw cloak, near the wisteria vine, looking up at its bare twisted remnants clinging to the old trellis. It was leafless now, but miraculously he had found there that single bloom he had sent her after their first night together. That she should have come to this spot cheered him. He called out to her.

She turned, hiding muddy hands under the rain cape, and he saw that the dark silk gown she still wore in mourning for her father was streaked with dirt along the hem and there was a smudge of mud near her nose where she had brushed back an errant tress of hair. But she smiled at him, and his heart melted with tenderness.

"What brought you here?" she asked, coming quickly to him.

"I was worried about you." He gestured at the desolate garden. "It still looks very sad, but in time it will be better."

"Oh? Will you keep it then?" she asked, her eyes growing wide with excitement.

"Of course. It is your home and your garden. I thought we might just rebuild a small summer house to start with, and perhaps quarters for a gardener to take care of the place."

"Oh, not a gardener," she cried. "I'll do that. Oh, thank you, Akitada!" Her face fell. "But the money? Can we afford it?"

He was secretly pleased about that "we." "Of course," he said. "Let me tell you my news. I had several visitors this morning. Captain Kobe stopped by first, and then we were honored by the bishop and young Lord Minamoto– who is now head of his clan so I must learn to address him as 'my lord' again."

She smiled. "He is a very nice boy. What news did the captain bring?"

"Okura hanged himself."

She looked down at her hands, which had crept from the folds of her gown and were now tightly clenched. "I am glad he killed himself," she said slowly. "Father would not have wished to be responsible for another human being's execution." Then she looked back up with a smile. "I suppose Bishop Sesshin and the young lord came to thank you for your help?"

"Yes, most generously. I had really not taken the boy seriously." He told her about the gold, happy in her delight in the sudden wealth. "Of course, they also expressed their best wishes on our marriage," he continued. Pausing, he added, more diffidently, "There was some other, rather puzzling talk about the lack of able administrators in the far north. It made me wonder."

Tamako's eyes widened. "What did the bishop say?"

Akitada told her what he could recall, watching her face as he spoke. She was still smiling, but with a certain fixity that dismayed him.

"Oh," she cried, "so much good news! I think you will receive a very grand assignment. Perhaps even a governorship!" She clapped her hands. "Heavens, what a signal honor at your age!" Biting her lip, she added quickly, "It is, of course, a well-deserved honor and a fine and wise choice. How very pleased your mother will be!"

Akitada asked softly, "And you? Are you pleased?"

She blushed and lowered her eyes. "Of course. It is a very great thing for you, for all of us." Then she asked breathlessly, with a slight catch in her voice, "How soon would you be leaving? There are so many things to be got ready. If you receive the appointment, you will be gone a long time . . . four years at least." She hung her head.

"There is no point in worrying about the preparations. It may all just be so much wishful thinking on my part. No doubt I was reading too much into a chance remark. And it is hoping for too much! I am only a clerk, a mere eighth grade in rank." He stretched out his hand to raise her face to his. Her eyes were filled with tears, but she smiled bravely. "Tamako," he asked, "I really wanted to know how you would feel about accompanying me to such an outpost of civilization."

"Oh!" Her whole face lit up. "You would take me with you then?" As he nodded, the tears spilled over and coursed down her cheeks, mingling with the streaks of dirt. She fell to her knees on the muddy ground and bowed. "Thank you, my husband. You have made this insignificant person very happy."

"Tamako!" he scolded, reaching for her. "Get up! There is no one about and no need at all for this cursed formality. And you have spoiled your gown."

She rose, chuckling tearfully and brushing at the black stains on her skirt. He took a tissue from his sleeve and wiped away the traces of muddy tears.

"I was so afraid you would not come," he confessed. "Most of the ladies I know would consider such an assignment one of the more agonizing torments of hell. There are none of the refinements of city life there, and I am told the winters last for eight long months."

"But look at me!" she said with a laugh, showing her dirty hands and her ruined gown. "I am nothing like those ladies and shall be far more comfortable in the uncivilized north than here, for I am a stranger both to proper behavior and to such fine clothes." She turned to glance around at the blackened landscape, and sighed blissfully. "I came to tell Father's spirit about our marriage. And now I am glad that he could share this good news and my happiness."

"And mine."

Taking his hand, Tamako took Akitada through the ruined garden to the wisteria.

"Look!" she said, bending to point to the twisted old trunk where it rose from the barren ground. Four or five bright green shoots had emerged from the roots and were already reaching eagerly upward. "And there, and over there!" She pointed to shrubs and young trees, and Akitada saw that they were all putting forth new leaves.

And then a nightingale began to sing in the old willow by the gate.

Historical Note

In the eleventh century, Heian Kyo (Kyoto) was the capital of Japan and its largest city. Like the Chinese capital Ch'ang-an, it was a perfect rectangle with a grid pattern of broad avenues and smaller streets, measuring about one third of the great Chinese metropolis, or two and a half by three and a half miles, with a population of about 250,000. The Imperial Palace, a separate city of over one hundred buildings housing the ministries and bureaus of the central administration and including the imperial residence, occupied the northernmost center of Heian Kyo. Both the capital and the Imperial Palace were walled or fenced and accessible by numerous gates. Rashomon (properly Rashoo-mon or Rajoo-mon, the "Rampart Gate") was the most famous gate to the capital but had fallen into neglect and disrepair. By the middle of the century it may well have ceased to exist altogether. A famous tale about this gate, later a part of Ryunosuke Akutagawa's "Rashoomon" and an award-winning film, is in the eleventh-century collection Konjaku Monogatari (no. 29/18). Heian Kyo is said to have been quite beautiful, with its wide willow-lined avenues, its palaces and aristocratic mansions in their tranquil gardens, its temples and government buildings with their blue-tiled roofs and red-lacquered columns and eaves, its rustic Shinto shrines, its parks filled with lakes and pavilions, its many waterways and rivers crossed by arched bridges, and its surrounding landscape of mountains and lakes dotted with secluded temples and summer villas. For some of the details of the description and the maps of Heian Kyo I am indebted to R.A.B. Ponsonby-Fane's work, Kyoto: The Old Capital of Japan.

The imperial university, located just southeast of the Imperial Palace, was founded in the eighth century and patterned after the Chinese system. It was, like the government, soon weakened by the self-interest of the aristocracy and catered only to the sons of the so-called "good people." In later years, its professors seem to have enjoyed neither decent pay nor respect, as we know from the role they play in 1004 in Lady Murasaki's Tale of Genji and from other sources. There were also private colleges, established by several great families like the Fujiwaras and Tachibanas and one institution for the lower classes, founded by the monk Kobo Daishi in one of the temples. The university followed Confucian teachings with emphasis on Chinese language and classics, to prepare the future civil servants for their professions. Students were drawn primarily from families of rank or from civil servants both in the capital and the provinces. They were males who ranged in age from the early teens to middle-age due to the tough qualifying examinations for admission and for intermediate and advanced degrees. Success in these examinations was the only path to a lucrative career for many lower-ranking individuals. By the eleventh century most contact with China had stopped and the authenticity of written and spoken Chinese had declined. Also, interest had shifted away from dry subjects like history, law and ritual to the much more entertaining practice of poetry. Nevertheless, the departments of this early institution of higher learning offered, in addition to Chinese language and literature and Confucian studies, also law, mathematics, fine arts and probably medicine.

Law enforcement in ancient Japan followed the Chinese pattern to some extent in that each city quarter had its own warden who was responsible for keeping the peace. The Imperial Palace was protected by several divisions of the imperial guard. Eventually a separate police force, the kebiishi, was added both in the capital and in the provinces. The kebiishi gradually took over all duties of law enforcement, including trial and punishment. There were several prisons in the capital, but imperial pardons were common and sweeping. Confessions were necessary for convictions and could be encouraged with beatings. The death penalty was extremely rare because of Buddhist teachings, and exile was usually substituted for the most heinous offenses such as treason or murder. Apparently this often was a fate equivalent to a slow death.

Transportation was cumbersome and slow. In the city, one mostly walked from place to place, unless one's rank entitled one to an oxdrawn carriage. In addition, both men and women used horses or litters for travel.

Relations between the sexes in early Japan strike westerners as liberal to the point of immorality. A young man's clandestine visits to the room of a young woman of his class were acknowledged between the lovers by an exchange of poetry the next morning, but need not be continued. If they were continued for three consecutive nights, a marriage had taken place and the groom was accepted into the bride's family by an offering of special rice cakes. He usually took up residence in his wife's home. The status of his new wife depended on his own status, his whim, or her parents' rank, for he might have several wives in addition to more casual alliances with concubines. He could also divorce his wives by simply informing them of such a decision. However, a young woman's family usually guarded her well, often arranging for a desirable visitation through a go-between after negotiating the bride's future status and her personal property. Occasionally, as in the case of the merchant Kurata, a family without sons might adopt the husband of a daughter.

The two state religions, Shinto and Buddhism, coexisted amicably. Shinto is the native religion, tied to Japanese gods and agricultural observances. Buddhism, which entered Japan from China through Korea, exerted a powerful influence on the aristocracy and the government. Certain important observances, such as the Kamo festival described in this novel, and agricultural rituals performed by the emperor and attended by the court, were Shinto, while the daily life from birth to death was governed by the worship of the buddhas, particularly Amida.

Many superstitions were common among all classes and well documented. One could not start the day without consulting the calendar for auspicious or inauspicious signs or directions. Puzzling events were immediately ascribed to the machinations of spirits or demons, or to human malevolence in the form of witchcraft or curses. Shinto is responsible for many taboos, including directional ones, and for the belief in shamanistic practices of divination and exorcism. Buddhism brought faith in relics and miracles along with the concepts of heaven and hell. Monsters, ghosts and demons abounded in the popular superstition, and contemporary literature is full of frightful occurrences. The story of Prince Yoakira's disappearance in this novel is based on two such tales from Konjaku Monogatari (nos. 15/20 and 27/9).

The calendar in ancient Japan was extremely complicated, being based on the Chinese hexagenary cycle and on named eras designated periodically by the government. Greatly simplified, there were roughly twelve months and four seasons as in the West, but the first month began a month later, in February. The work week lasted six days, began at dawn, and was followed by a day of leisure. By the Chinese system, the day was divided into twelve two-hour segments. Time was kept by water clocks, and the hours were announced by guards, watchmen and temple bells. The changing seasons brought many festivities. In this novel, the return of the Kamo virgin, an imperial princess, to her temple on the shore of the Kamo River is celebrated toward the end of spring. On this occasion people and houses were decorated with the leaves of the aoi plant (a member of the ginger family) which was sacred to the Kamo observance. (The modern meaning of aoi is hollyhock, a different plant but one which is more familiar to modern readers.)

It is not clear whether Heian Kyo had a separate pleasure quarter in the eleventh century, but within a few centuries there were two of these in the city. Female entertainers were certainly known at the time. They earned a living by dancing, singing and playing instruments and were held in slightly higher esteem than the later geisha.

The eating and drinking habits of the eleventh century differed little from later times. Tea drinking had not yet become common. Most people drank rice wine. Meat, with the exception of wild fowl, was rarely consumed. The diet of the poor consisted of vegetables, beans and millet. The well-to-do added rice, fish and fruit.

Many customs, superstitions, and taboos surrounded death. Although interment was known, cremation was preferred after the arrival of Buddhism. For forty-nine days after death the spirit of the deceased was thought to linger in his home (hence Akitada's irrational sensations in the prince's rooms). The dead could also haunt the living if they had suffered unjustly, a fact which accounts for much of Tora's aversion to ghosts. In general, contact with the dead was a form of defilement according to Shinto beliefs, and all funeral arrangements were therefore in the hands of Buddhist monks.