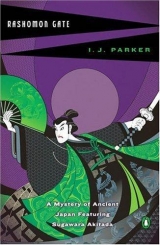

Текст книги "Rashomon Gate "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

"Please!" Her voice was tight and urgent. "I know that Father has spoken to you about marriage. But you must not do it. I beg you, if you care for me at all . . . like the sister you said I was to you . . . do not make an offer tonight, or ever! Oh, Akitada, I am so sorry, but I simply cannot marry you."

"But why not?" Aghast, he stepped closer but she flinched away again.

"Do not ask me why. I beg you to make this easy for me, and I shall always be grateful."

Six

The Kamo Procession

The rest of that evening would always hold a vaguely nightmarish quality for Akitada. He had informed Hirata that there would be no marriage, taking the blame upon himself by claiming the uncertainty of his future and his obligation to his family. Hirata had accepted his refusal without comment.

The subsequent dinner was a dismal affair. Tamako sat beside Akitada with downcast eyes, pushing her food around and eating very little, while her father looked sadly at them, sighing deeply from time to time.

At home another confrontation awaited him. His mother was still up and received the news as a personal insult.

"May I ask who broke off the engagement? And why?" she snapped.

Akitada's heart sank. He foresaw problems when his family met Tamako on the occasion of the Kamo procession. "I presumed on our friendship," he said. "It was completely my mistake."

"I see. Then your offer was rejected. What an affront! And to think that a Sugawara consented to marry a mere Hirata!" His mother's eyes flashed with anger.

"It was not like that," Akitada protested. Fear for Tamako caused him to add more sharply, "And I hope you and my sisters will remember tomorrow to treat Tamako with the respect due to a friend of the family."

His mother drew herself up stiffly. "Do not take it upon yourself to teach me manners! My grandfather was a direct descendant of Emperor Itoku, and I have served in the palace. I shall always know what is due our guests. You may leave! It is past my bedtime."

• • •

The morning of the Kamo procession dawned splendidly. It was a holiday, dedicated to the guardian spirit of the capital city, and an excuse for high and low to enjoy the final days of spring. Tora had rented the high-wheeled ox cart at sunrise and was now backing it up to the veranda of the main house so that the Sugawara ladies could enter it without dirtying their skirts in the courtyard.

Akitada's sisters emerged first, preening in their prettiest gowns and chattering excitedly. They were not twenty yet, and a mystery to Akitada who had spend many years away from home and only remembered them as a couple of round-faced children who seemed to follow him everywhere. Since his return he had decided that they had become silly but good-hearted girls. Today he met their exuberance without so much as a smile. The sight of their brother's joyless face caused them to fall abruptly silent and climb into the carriage without further ado.

Not so Lady Sugawara. She arrived dressed in a gorgeous rose-colored Chinese robe embroidered with peonies, a part of her dowry, but came to an abrupt halt when she saw the plain, woven carriage.

"You do not expect me to ride in this, do you?" she asked Akitada icily. "We have never attended a public affair in a rented conveyance. Our own family carriage with our crest was always drawn up behind our viewing stand."

"We no longer have the privilege of a private carriage, mother," Akitada pointed out wearily.

"And it appears my son no longer has friends who will oblige him with theirs," his mother shot back nastily.

Akitada sighed inwardly. He had offended and would have to soothe his mother's temper. "My sisters have looked forward to this treat for years," he reminded her, "and without you neither they nor our guest will be able to attend the procession."

Lady Sugawara tossed her head, but entered the carriage without further protest.

Akitada saw his family off before turning his own steps towards the Hirata residence.

The weather, poised between spring and summer, made the Kamo festival an occasion for romance. Even the most strictly raised young ladies were permitted light flirtations with young gentlemen without incurring censure. As Akitada walked, he saw young couples strolling towards First Avenue, where the procession would pass on its way from the emperor's palace to the Kamo shrines outside the city. They were dressed in their best finery and wore hollyhock blossoms, sacred to the Kamo virgin, on their hats and in their hair.

Akitada wished he had arranged for a sedan chair. Until last night he had looked forward to the privilege of walking beside Tamako as her acknowledged suitor. Now the arrangement was awkward for both of them, but all the chair bearers were long since committed.

Tamako was ready when he arrived at the Hirata house. She had never looked more beautiful. The many-layered silk robes, reds and pinks under shades of gradually darkening greens, suited her slender, elegant beauty. In her hand, she carried the straw hat with the veil worn by all women of good family when walking in public, and her glossy black hair brought out golden tones in her face. Akitada recalled that Tamako spent much time in the sun, tending to her garden. It was unfashionable, but he admired the healthy glow of her skin. Then their eyes met, and both looked away simultaneously.

"Good morning, Akitada," Tamako said, bowing formally. "It's very kind of you to come. Are you certain you don't mind taking me along?"

"Of course not." He managed a smile. "You look very elegant. I am sorry but I did not get a chair. Will you mind walking?"

"Not at all. It is a beautiful day. Shall we go?"

In the willow above them, a bird burst into song, and behind her the garden shimmered in the morning sun.

Akitada nodded miserably. They had never spoken to each other like strangers.

Tamako paused at the gate and bent to an earthenware pot which held bunches of flowering hollyhocks.

"I did not know what color your robe would be," she said, "so I cut some of each color. I think this white one will look well. What do you think?"

"Yes. It was kind of you to remember. I forgot that also."

"Don't be silly. I have a whole garden full of hollyhocks!"

She reached up and fastened the white blossoms and green leaves to his court hat while he bent his head. Tamako was tall for a woman, and her face, intent on the task of arranging the blooms, was close to his. Akitada's eyes were on her lips, very pretty lips, slightly open so that he could just see a tip of her tongue between the white teeth. A subtle fragrance escaped from her sleeves and Akitada closed his eyes. A fierce wave of despair seized him and he stepped back abruptly.

"Oh," she breathed, her eyes flying to his.

He bent and caught up a cluster of pale pink blossoms. Uncertainly he looked at her hair, gleaming bluish-black in the sun and caught on her back with a broad white silk bow. "Where should I . . . ?"

"I think in my sash. The hat would crush them in my hair. Here, I can do it." She took the hollyhocks from his nerveless fingers and tucked them in her sash. Putting on the hat and tying it, she arranged the veil and said, "All ready."

They walked most of the way without saying much. Tamako commented on the delightful weather, and Akitada agreed that it was so. He really wanted to ask her why she could not marry him. All night he had lain awake wondering. Was there another man, perhaps? It was the most likely explanation. At the thought he felt his stomach twist with helpless anger. He had been a fool not to ask her himself months ago. But would not her father have known of another attachment? Perhaps he was too poor? Too tall and gangly? Too ugly with his heavy, beetling brows and his long face? He walked beside her in silent misery.

Two blocks later he pointed out the antics of some children and Tamako remarked that it was a very happy time for the youngsters. The thought threw them into an even deeper depression until the passing of an elegant carriage caused both of them to speak at the same moment, to apologize, and to fall silent again. The invisible barrier between them made their time together extremely distressing to Akitada. When they finally arrived at the viewing stand, he felt more relief that their walk was over than worry about his mother's reception of Tamako.

Lady Sugawara and his sisters had been watching their approach. Akitada made the introductions, and Tamako stepped forward to bow deeply before his mother. She said, "This humble person is quite unable to express her feelings at your ladyship's goodness."

"Not at all. Not at all. Welcome, child!" Lady Sugawara's voice was warm, and she smiled in the kindest manner. "I see," she said, "my boorish son has neglected to provide you with a sedan chair. I apologize for him. Please come and sit with us!" She patted a cushion which had been placed between herself and her daughters.

Tamako thanked her and bowed again before greeting Akitada's sisters and taking her place beside them.

Having seen her installed, Akitada cast an imploring glance at his mother, who looked back blandly. He made his excuses, claiming that he had to meet friends, and escaped. It was a cowardly act, but he consoled himself that his mother would have resented his presence as a sign of distrust.

Miserably he wandered along First Avenue towards the gate through which the procession would leave the city on its way to the shrines on the banks of the Kamo River. Neither he nor his family intended to follow it the whole way.

The viewing stands stretched along the entire length of the parade route and were already well filled with onlookers. Above some flew banners with the crests of the ruling families of the realm. Between the stands or behind them, elegant painted and gilded carriages of the nobility had been placed side by side, the oxen unhitched and the shafts propped up on supports. From beneath the woven shades the scented and many-colored sleeves of court ladies protruded. Passing dandies guessed at the occupants and made flattering comments on the color combinations in hopes of eliciting a giggle or even a wave with a fan.

The crowds thickened near the palaces of the great nobles along the southern side of the street. Here and there the imperial guard was in evidence, mounted on prancing horses, their bows and quivers slung over their shoulders.

Suddenly Akitada saw a familiar face. Young Minamoto was seated on one of the stands. Next to him was a tall man in his thirties. The stand was draped with the Minamoto crests, and Akitada wondered if the tall man might be Lord Sakanoue. On an impulse he crossed the street. He saw that the boy was wearing particularly fine robes, but his face was pale and set. He seemed to look at the spectacle in the street with blank eyes. The man next to him wore a haughty and forbidding expression. The slitted eyes and impassive features seemed to belong to a statue rather than a living, breathing human being.

Then the boy saw Akitada and rose to bow. Turning to his companion, he said, "Allow me to present one of my professors. Doctor Sugawara, my lord."

The impassive eyes flicked Akitada with a glance. The stony head barely nodded.

"This is Lord Sakanoue, my guardian," the boy explained.

Akitada bowed, saying with a smile, "I had hoped to make your acquaintance, my lord, to tell you what a fine student your ward is. Now I am glad to see that you are giving him a day's outing. He deserves it. He has been working very hard."

"It is his duty to work hard," said the other curtly, in a surprisingly high, nasal voice. "It is also his duty to attend official events. As his teacher you should know this."

Akitada found the man's words offensive and therefore did not acknowledge them. Instead he turned to the boy again, saying, "You must be enjoying your visit with your family."

The boy colored. "My sister could not attend," he murmured, "and there is no one else."

"You may continue your conversation some other time," barked the high voice of Sakanoue. "The procession is about to start. It is very unseemly to stand about chatting when people have come to observe."

The dismissal was as rude as it was final. Akitada bowed and withdrew without another word. But he saw the tears of shame in the boy's eyes and blamed himself for having provoked the unpleasant scene with his impulsive action.

He continued his stroll along the stands worrying about the boy, following the rest of the sight-seeing and socializing crowd absentmindedly until the noise in one place caused him to look up. He saw four stands, elaborately decked out with flags, greenery and hollyhocks and filled with a large crowd of boisterous celebrants in silk robes of every shade and pattern. The Fujiwara crest flew gaily in the breeze above all four stands. Akitada scanned the faces. Somewhere in the middle he found the rotund figure and smiling face of his friend Kosehira. Evidently he had strayed into a party hosted by Kosehira, and he ducked his head and passed by quickly.

But Kosehira had already seen him. He was shouting, "Akitada! Akitada! Up here!" When Akitada turned, Kosehira had climbed upon his seat and was waving excitedly. "By all that's holy! It is you! Come up here, man!"

Akitada feigned pleased surprise and clambered up. Kosehira made room next to himself, found a pillow for Akitada, introduced him around and insisted he stay for the procession. In the distance sounded the great drum, and they could hear the runners' first shouts to "make way." Akitada settled down to enjoy himself.

The procession came their way so quickly that there was little time to exchange news with Kosehira. In the vanguard walked the Shinto priests in their white robes. They were followed by officials in bright yellow silk who carried large red and gold fans on long poles.

Someone pressed a lacquer box filled with elegant snacks into Akitada's hand, and Kosehira urged him to eat. Just then flag bearers passed, followed by an ox-drawn carriage covered with blooming wisteria branches. Their sight and scent reminded Akitada of Tamako and he closed the lacquer box on his lap. He had no appetite.

"Isn't he magnificent?" asked Kosehira, pointing to the huge ox. "He belongs to Sakanoue, who has donated him to the Kamo shrine. Rumor has it that that there have been bad omens about his marriage."

Sakanoue again! Akitada glanced at the beast, heavily garlanded with wisteria, draped with orange silk tassels, and led by a handsome youth in a colorful court robe. It was more likely that the arrogant man he had just met was more concerned about currying favor with the emperor than buying off the gods.

Immediately behind the ox rode the emperor's messenger to the Kamo deity. A handsome young man in costly robes, he sat his horse well. The spirited horse was a rare dappled gray and elicited cries of admiration. He pranced, causing the red silk tassels hanging from his head to bounce, and the young man on his back laughed out loud. When his eyes fell on Kosehira's stand, he flashed a broad smile towards them and waved before passing on.

"The empress's brother," Kosehira shouted into Akitada's ear over the applause of the crowd. "Not at all bad, considering he was up most of the night with us, drinking and reciting poems." The rest of his words were drowned out by the rhythmic booming of the great drum which made its appearance next. It travelled on another decorated ox-drawn carriage and was beaten by a muscular giant of a man, stripped to the waist and already glistening with perspiration in the cool morning air.

Akitada was glad there was no need to make conversation. He had fallen into a depression, and Kosehira's reference to the poem-composing nobleman had reminded him of this evening's competition in the Spring Garden, which in turn called to mind the brutal murder of the girl, his assignment at the university and his unease about Hirata.

The drum passed, followed by a group of beautifully gowned and masked dancers who paused briefly before their stand to give a performance. Kosehira leaned towards him again. "I hear you are teaching at the university now," he said. "Your talents are wasted, my friend. Heaven knows there is too much trouble in the world for a man of your ability to pass his time in the schoolroom."

Akitada sighed. "I don't know what trouble you are thinking of, but even at a university there may be the occasional puzzle to solve."

Kosehira raised his eyebrows comically. "A puzzle? You don't mean it?" he cried, slapping Akitada on the back with a chuckle. "Wonderful! I want the whole story when it is all done. But look! Here comes the virgin! Gorgeous litter, isn't it? I'm told the little princess is the prettiest creature. Some lucky man will take her to wife some day and make his fortune to boot."

They watched the litter, borne on the shoulders of twenty young noblemen in matching pale green and light purple robes, sway past in its gilded glory. Only the virgin's sleeves, many layers of gauzelike silk, shaded from the palest cream to deepest red, showed under the decorated curtains which hid her from view.

Akitada's mind was on another young woman and his failure to take her to wife. He sighed.

"Why so glum?" asked Kosehira. "Is it the problem at the university?"

"That, and other matters."

"Can I help?"

"No. Thank you. But tell me, are you acquainted with Lord Sakanoue?"

An expression of extreme distaste crossed Kosehira's normally cheerful, round face. "Certainly not. Don't like the fellow," he said. "There's talk that he forced Prince Yoakira's granddaughter to marry him. People say he plans to do her little brother out of his inheritance."

"Is this common gossip?" Akitada asked, surprised.

"Well, yes and no." Kosehira looked uncomfortable. "Some of us who knew the old prince are very concerned. You see, the old man never liked Sakanoue. Sakanoue is not a nice person. I myself witnessed an incident the other day where he pushed ahead of old Lady Kose, the late emperor's nurse. She cried out in alarm, and he said something very rude about senile old hags. I was shocked."

"He is definitely not nice," Akitada agreed. "I just had a taste of his lack of manners myself. The grandson is one of my students, by the way."

Kosehira's eyes widened in surmise.

Akitada added quickly, "No, no. He is not the reason I am at the university. Besides, a man's lack of manners does not necessarily prove that he has criminal intentions."

Kosehira shook his head. "In this instance I don't agree with you," he said. "But in any case it is a very good thing you're there. If anyone can get to the bottom of the affair, it is you. Just be careful! Sakanoue may be dangerous. Incidentally, he is some kind of cousin to the family. There was some talk after the old prince's son died, that he planned to adopt Sakanoue, but he evidently decided against it and raised his grandson instead."

Akitada would have pursued the matter, but Kosehira's other neighbor asked his host a question. On the street, a group of musicians was passing and at that moment they raised their flutes to their lips and played an ancient melody. Instantly Akitada was entranced. This was even better than Sato's lute playing, and it looked a great deal easier. For a moment he considered whether Sato might consent to teach him the rudiments, but that reminded him again of the murdered girl and her relationship with the music teacher. Sato must certainly have been interrogated by the police by now. Perhaps he had even been arrested.

With the flutists, the procession drew to its close. A final group of white-robed priests passed, and then the spectators fell in behind, following on foot or in their carriages. The stands were emptying rapidly, and Kosehira turned to Akitada.

"Will you join me in my carriage?" he asked.

"No. I must see my family and a guest home. Besides I have made the journey many times."

They parted with promises to meet again soon, and Akitada hurried back. But before he reached their viewing stand, he was hailed. It was the police captain he had met the day before.

"Glad to run into you," the man greeted him. "If you can spare the time, I'd like you to come to the jail with me. We have arrested a suspect in the park murder. He had a woman's red sash on him; I'd like you to identify it."

The picture of the old beggar flashed through Akitada's mind. If he was the suspect, he would have to try to get him released, but first he must see to his family and Tamako. He explained his dilemma to Kobe and promised to come as soon as he could.

To his surprised relief, he found that Lady Sugawara had invited Tamako to share their noon rice.

"And we will send her home safely in the rented carriage," she told her son, "since you cannot be trusted to extend the proper courtesies to a young lady."

Akitada's eyes went to Tamako. She looked calm and nodded with a little smile. "I told your mother how pleasant our walk was," she said, "but she insists that I must ride home in style. I am sure you must be very busy, and we are having a lovely time talking about you."

Akitada's sisters broke into giggles, and his mother smiled indulgently. Somewhat dazed, Akitada saw the ladies into their carriage and gave Tora instructions about taking Tamako home. Then he hurried to the prison.

The municipal jail was only a few blocks away. He found Kobe pacing in the guard room, a bare hall primarily decorated with chains, whips, handcuffs and leg irons hanging from hooks on the walls.

"Ah. There you are," Kobe said in lieu of a greeting. On a rickety and scarred wooden table lay a bulky paper package tied with cord. Kobe tore it open, and took out a wrinkled length of bright red brocade with a small pattern of flowers and birds in many colors. "Do you recognize it?"

Akitada stepped closer. "It looks like the one the girl wore to her lesson," he said, touching the fabric. The creases were particularly deep in two places. It looked as if the sash had been looped around something, and then pulled and twisted sharply. He glanced at Kobe. "This must have been used to strangle her."

Kobe nodded. He picked up the sash, refolded it, and put it in his sleeve. "Follow me!" he said, heading out the door.

They passed down a long, dingy corridor with many cell doors. Haggard faces appeared at the grates, but none of the prisoners spoke. At the end of the corridor a door opened onto a veranda which looked down into the jail's courtyard, where a dismal group awaited them. Two brutish-looking guards jumped up and jerked a bedraggled figure between them erect. With a thin cry of pain the old beggar staggered to his feet. Because his ankles were chained and his hands tied behind his back, he lost his balance and fell against one of the guards, who immediately clouted him over the head. The old man sagged to his knees again. His chin sank to his chest and he whimpered.

"Why are you holding this poor old man?" Akitada cried.

Kobe shot him a glance. "He is the suspect in the murder."

"Impossible! And what have you done to him? There is blood on his clothes."

"He has been whipped. Such methods are used when suspects refuse to cooperate."

"But he is only an old man. How could he have had the strength to kill that young woman, let alone—"

Kobe interrupted sharply, "May I remind you that we are not alone?"

Akitada flushed. "Why did you bring me here?" he said as sharply.

"I wanted you to hear what he has to say. At first we thought he was simply stubborn and facetious, but I have since had second thoughts." Kobe turned to the group in the yard and shouted, "Umakai? Look at this!" Removing the brocade sash from his sleeve, he held it up.

The beggar continued to sag between the burly guards. One of them kicked him. "Pay attention, you piece of dung!" he snarled. The old man slowly raised his face to look up at the veranda. Akitada's stomach contracted with pity. The old face was bruised and bloodied, and tears ran down the wrinkled cheeks.

"Tell this gentleman who gave you the pretty red sash!" shouted Kobe.

The beggar trembled and shook his head violently. The guard to his left raised a whip, but Kobe stopped him. "Don't worry, Umakai!" he called. "You will not be beaten if you tell us what we want to know. This gentleman was in the park and may have seen the same thing you saw."

The old man looked at Akitada, thought about it, and shook his head again. Kobe frowned. "Listen to me, Umakai," he roared. "I don't have time to waste. Either you talk, or I'll send for the bamboo switches. Do you understand?"

Akitada moved. "Captain Kobe," he said through clenched teeth, "I will not watch an innocent man being beaten. If you wish me to remain, I suggest we go inside, dispense with those two fellows, and give the old man something to drink to loosen his tongue."

Kobe suddenly smiled, his white teeth flashing from his bearded face. "But of course," he said smoothly. "Why not?"

The beggar was taken to the guard room, untied, and settled on an old cushion. Kobe produced a pitcher of wine and poured him a cup. Umakai moved clumsily because his wrists were swollen, but he managed to raise the cup to his mouth and empty it in a single gulp. He gave a deep sigh, and Kobe refilled the cup. The old man drank again. This time he burped and clutched his stomach.

"Are you in pain?" Akitada asked anxiously.

"Not bad, not bad," the old one muttered, giving him his attention for a moment. "Is it true you saw him?" he asked. His eyes were curiously unsteady, shifting about between Akitada, Kobe and the objects in the room.

"I may have," Akitada said cautiously. "What did he look like?"

"What did he look like? Why, he looks like all of them. They all look alike, don't they?"

Akitada thought for a moment. It occurred to him that the beggar must have seen a guard or a policeman. "You mean he wore a uniform?"

Umakai chuckled. "A uniform? I guess you could call it that."

"It was a red coat, wasn't it?" Akitada shot a glance at Kobe, who raised his eyebrows.

The beggar stared at Akitada. "No, a red hat," he said. "Don't you know anything?"

"A red hat!" Akitada looked at Kobe again, who grinned back broadly and nodded.

"But . . . nobody wears a red hat," Akitada protested.

"Oh, I don't know," said Kobe, studying the ceiling. "Ask him the name of the fellow with the red hat!"

Feeling foolish, Akitada turned back to the beggar and asked, "Did he have a name?"

Umakai gave him a pitying look. "Of course! Everybody knows his name. Stupid question! There are hundreds of them all over the place."

Akitada sighed. Kobe must be playing an embarrassing joke on him. The old beggar was clearly mad. But he decided to play along. "Please tell me. I seem to have forgotten it," he said.

He received a sympathetic glance from the old man. "So you've got that trouble too. My head hurts fearfully some days, and I can't remember where I slept the night before. But I would never forget Jizo."

"Jizo?" Akitada turned to Kobe, who was grinning and nodding his head. "Does he mean the god Jizo? The one who protects travellers?"

"And small children," said Kobe. "In fact, that is why mothers sew red hats and bibs for his statues."

Umakai cried, "Now do you remember? He had his red hat on and he gave me a present. Did he give you a present, too?"

"No," said Akitada. "I wish he had. Where did you meet Jizo?"

The old man frowned. "I don't know. Someplace. There's one on the corner of Third Avenue. Third and Suzaku. You go and ask him! Ask him for a present too! And tell him Umakai says hello."

"Thank you. I will. Did you ask Jizo for the pretty red sash?"

"No. I just stuck out my empty bowl as he was passing. And right away he put the pretty red silk in it."

"I see I must get myself a bowl," said Akitada with a straight face. "But isn't the bowl for food? A man can't eat silk when he is hungry."

"Wasn't a bit hungry. Had some bean soup at city hall. The clerks there are my friends. Would you tell them about me?" Umakai's eyes were filling with tears again. "Tell them to come get me! And tell Jizo they took my present away and beat me!"

Akitada turned to Kobe. "Surely . . ." he said.

Kobe walked over to the beggar and helped him up. "Come, Umakai," he said. "We'll find you a nice place to sleep and some hot food. By tomorrow you'll feel much better." He clapped his hands and when a constable appeared, he told him, "Take him away. Give him bedding and see that he gets some food, but lock him up!"

The guard led the shuffling Umakai out.

Kobe turned, smiling broadly. Akitada met his eyes in stony silence.

"I must congratulate you," said the captain, rubbing his hands. "Your method worked. Yesterday the tale sounded like a rigmarole. Now we know that someone in a red hat or cap gave him the sash. He is too simple to make up such a tale."

Akitada could not remember ever having felt so angry. "Since it is now apparent to you," he said icily, "that the man is innocent of the murder and told the truth all along, what other torments can you possibly be planning for him? Any normal man would have been distraught at having put another human being to the torture, but you are evidently saving him for another day. You will either release him immediately with profuse apologies, or I will personally bring charges against you."

Kobe's eyes had narrowed. He remained silent for a minute. Then he said stiffly, "I have been aware of the fact that you disapprove of my methods. Perhaps I should remind you that these methods are mandated by law and depend on the circumstances. Umakai was found on the scene of a crime. In fact, he was the only person there, with the exception of yourself and your servant. Furthermore, he had the weapon, such as it is, on his person. Last night it was not obvious that he was simpleminded. I was afraid that he was shielding an accomplice. Criminals often work with beggars. In any case, I followed the prescribed procedure as I am sworn to. As to your demand that I release him now: It should have occurred to you that he is our only witness to the identity of the killer. Beggars do not, as a rule, have a permanent home. They sleep wherever they happen to find shelter, this time of year often in the street. If I released him, we would not find him again. And the killer might."