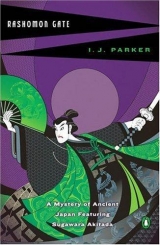

Текст книги "Rashomon Gate "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Eighteen

The Prince's Friends

On their way home, Akitada and Tora stopped by the university to pick up some student papers Akitada had forgotten.

It was getting dark, though not noticeably cooler. Tora glanced at the sky and remarked, "We need rain. I haven't seen it this dry in years. It's a wonder there haven't been more fires."

Akitada nodded. The streets and courtyards of the university lay deserted, grass and weeds browned and dusty. The students were either in their dormitories or had left for visits with friends and relatives in the city. Guiltily Akitada remembered the little lord.

When he had gathered up the papers in his office he told Tora, "Let us pay a visit to Lord Minamoto. If he is not doing anything tomorrow, he might like to come for a visit."

They found the boy in his room, reading a book. He looked small and forlorn, but cheered up when he saw them. Bowing to Akitada, he said, "You are most welcome, sir. Have you come to report some news?"

Akitada smiled and sat down. "In a manner of speaking. We have solved the case of the murdered girl. It was mostly due to Tora's work. A silk merchant named Kurata was the culprit."

Lord Minamoto clapped his hands. "Oh, good for you, Tora!" he cried. Turning back to Akitada, he said, "So it was not poor Rabbit! I am glad you took an interest, sir. Is there no news about my case?"

"No. Not yet." Akitada looked around the small room. He thought again of the boy's great-uncle. Could the man not have done something for this child? Aloud he asked, "And you? Any plans for tomorrow?"

The boy's face darkened. "No, sir."

"Well then, perhaps you might like to visit us?"

The young face lit up. "Oh, could I? Thank you. Will you be there, Tora?"

Akitada answered for Tora. "Probably. Also my mother, my two sisters, and I."

Blushing, Lord Minamoto apologized, saying politely, "Please forgive my rudeness, sir. I am looking forward to meeting your family and having an opportunity to converse with you."

Akitada rose. "Good. Tora will come to pick you up right after your morning rice."

The boy stood also. "I shall be very happy to get away for a while," he confided. "There have been some new men working outside. They keep staring into my room and they give me the shivers. I think they look more like rough types, bandits or pirates, than servants. One of them was sweeping the veranda, but he does not know how to use a broom."

Akitada exchanged a glance with Tora. "How long have they been here?" he asked the boy.

"Since yesterday."

The thought that Sakanoue had sent thugs to watch the boy, or worse, crossed Akitada's mind instantly. Sesshin must have warned Sakanoue about Akitada's visit. Once again Akitada was reminded that only this child stood between Sakanoue and total control of the Minamoto fortune. It had been a terrible mistake to tell that old fake of a priest about his suspicions!

"Take a look outside, Tora," he said.

Tora disappeared and returned shortly. "A big rascal with an ugly face is out front. There's nobody out back."

"Sadamu," said Akitada to the boy, lowering his voice, "I don't like the idea of leaving you here until we have checked out the new help. I think we will take you home with us tonight."

The boy was on his feet in an instant, his face bright with excitement. Tossing a few books and clothes into a large square of silk, he knotted it and handed the bundle to Tora. Then he took up his sword and said, "I am ready, sir."

"Perhaps," said Akitada softly, "it would be better if you left quietly the back way. Tora and I are going out by the front. Tora will then double back and meet you at the back door."

The young lord's eyes flashed with the thrill of danger. He slung the strap of his sword over his shoulder, tested its readiness, and then took the bundle back from Tora, whispering, "I shall be waiting."

The maneuver was carried out with great success. Akitada and the boy walked quickly out of the dormitory enclosure and down the deserted street to the gate, while Tora lingered behind, making sure they were not being followed.

At home, Akitada installed his guest in his own room and went to inform his mother about their visitor. He was nervous about her reaction to the unannounced guest. It would be very awkward if she retaliated by refusing to receive Lord Minamoto.

But he should have known his mother better. As soon as he mentioned the boy's name, her eyes sparkled with interest.

"Prince Yoakira's little grandson? How charming! Finally you are cultivating the proper connections. You never mentioned that the poor fatherless child is your student. Nothing could be better! I shall ask him to consider this his home from now on. It is absolutely incomprehensible to me how his family could allow a boy of his background to mingle with unsuitable companions in a common dormitory." She made it sound as if young Sadamu had been condemned to live in an outcast village.

"It is a temporary arrangement only," said Akitada, "as is his visit here. I am merely giving the boy an outing, since tomorrow is a holiday."

"Don't be foolish!" snapped his mother. "This is your chance to become his private tutor. Then, as he rises in the world, so will you." She clapped her hands.

An elderly maid appeared and fell to her knees, waiting for her mistress's instructions with her head bowed to the floor. Akitada cringed inwardly. The woman, Kumoi, had been his nurse and his mother's before him. She was getting old and frail. His mother's insistence on proper respect struck him as unnecessarily cruel.

"Ah, Kumoi," Lady Sugawara said briskly. "Make haste to ready the large chamber next to my son's room for our noble guest. Have the maid scrub the floor and then move in several of the best grass mats from other rooms. Then you may go to the storehouse and select suitable furnishings. The best of everything– screens, scroll paintings, braziers, clothes boxes, lamp stands– you know what is necessary. And look for some games suitable for a boy of eleven as well. The bedding is to be of quilted silk only. Arrange everything tastefully and then return. Now hurry! I will inspect his room personally."

Kumoi wordlessly knocked her head against the floorboards and scuttled from the room.

"There was no need to burden the poor woman this way," said Akitada. "She is getting too old– and besides, young Minamoto is merely a child."

His mother fixed him with a cold eye. "Clearly you do not know what is owed to someone of that child's standing," she snapped. "Treat him well, and he may reward you some day. Treat him shabbily, and you have made an enemy for life. To people of his background, nothing is more disagreeable than low surroundings."

Akitada remembered the student dormitories and suppressed a smile. "Oh, I don't know," he said insidiously. "His lordship has become very fond of Tora since they flew kites together. He looks forward to spending most of his time with our servant."

His mother was taken aback. Then she snorted, "You should never have permitted that association! The boy's family will be shocked to the core. You will think up something to distract the child from Tora. Teach him football or something!"

Akitada smiled. "I hope to spend a little time with the boy," he said, adding as an afterthought, "In fact, the situation is a little like my own first stay with the Hiratas. I was not much older than he."

His year in the Hirata family was a sore subject between them, and his mother stiffened. With a frown she said, "That reminds me. Someone brought a letter for you from Tamako. She very properly enclosed it in a cover note to me. Here." She fished a slim, folded sheet from her sash and passed it to Akitada.

His heart skipped. The old pain, the many unanswered questions, were back in an instant. Struggling to maintain his composure, he said, "Thank you, Mother." The note he tucked, unread, in his sleeve, adding, "I had better go now and see to our guest." Bowing, he withdrew quickly.

Out in the corridor, he unfolded Tamako's letter with trembling hands. Whatever he had expected– and should not have expected in a letter meant to be read by his mother– he was disappointed. The note was extremely short and the form of address clearly put him in his place:

"Dear Honorable Elder Brother. Forgive this importunity, but could you look in on Father? His health is poor and we fear the worst. Your obedient younger sister."

Akitada refolded the paper in a state of confused unhappiness. He recalled guiltily the drawn face of Hirata and his repeated attempts to speak to Akitada. Could he be truly ill? Akitada blamed himself for the cold distance he had put between them the last few days. What if the older man's collapse had been more than indigestion? He really should have taken him home and explained matters to Tamako.

But seeing Tamako was more than he could face. It was impossible! It would open up too many old wounds. Akitada recalled bitterly that it had been her wish to discuss her father's condition that had started the whole miserable affair.

Twisting the letter in his hands, he wondered what to do. He walked out into the garden and started pacing. After some thought, he decided that Tamako intended him to look in on her father at the university. He would make it a point to see Hirata on the very next day of classes. Afterwards he could communicate the results to his "younger sister" by letter.

This problem settled, he tucked the letter in his sash and returned to his room and offered the boy some hot tea and sweet plums.

"Where is Tora?" asked Sadamu through a full mouth.

Tora! Akitada had forgotten all about him. What could have delayed him this long? He excused himself and headed for the courtyard to look for Tora. To his relief, the gate opened the moment he stepped out, and the truant slipped in.

Now that he was no longer worried, Akitada became irritated. "Where have you been all this time?" he snapped.

Tora was breathing hard. "They followed us," he said. "I saw them as soon as I passed through the university gate. You and the little lord had already turned the corner."

"Did you lose your pursuers?"

"Not right away. The bastards were good. And there may have been more than two. One of them is the big guy with the ugly mug who was outside the dormitory; another one is skinny, with a sneaky face and the longest legs I ever saw. I swear that rat can jump over whole city blocks. I must have spent the last hour running up and down streets and alleys. They almost caught up with me twice. I had to double back again and take another street. I think I lost them."

"You think?" Akitada felt a lump in his stomach. "I don't like this," he said. "Sakanoue means the child harm. If he felt any parental concern for the boy's safety, he could have contacted the university authorities." He paused. "We must consider what to do if they find their way here. This house is not safe."

Looking around the compound, Akitada saw that the mud walls were tall and in good repair, but an agile thief could climb them. The gates could be secured, but not against large numbers.

He shook his head. "I am afraid I may have exposed the child to much greater danger here than in his dormitory. Besides, I am jeopardizing the lives of my family. You and I are the only able-bodied men here. Seimei is too old and the boy too young to be much use against trained bandits. We must hire men to help us keep watch and, if necessary, defend the women and the boy."

Tora's face lit up. "I know the very guys, sir."

Akitada raised his brows.

"Hitomaro and Monk."

"Don't be ridiculous. After what they did to you? That is all we need, two known criminals inside our gates."

"They aren't criminals. They were only helping Spike and Nail because they thought the police had killed Umakai, and they figured I was one of them. Sir, they need the work and they'll do anything. They told me if they don't find some work quick, they'll have to eat what Monk can beg."

"It serves them right. If they had not broken some law, they would not be in this fix. Desperate men are capable of anything. Would you set a hungry cat to guard your fish?"

Tora's eyes flashed. "That's what Seimei said when I needed a job."

Remembering the incident, Akitada wavered.

Tora touched his arm. There were tears in his eyes. "Please, sir, trust me in this. At least talk to them."

Akitada was so astonished that his jaw dropped. "Very well. Bring them here and I will talk to them, but no promises. And I hope you know what you are doing."

Tora jumped up. "Thank you, sir! You won't regret it!" He dashed to the gate, slipped out and was gone.

Lady Sugawara chose to preside over the evening meal. Considering the short notice it was surprisingly splendid, including in addition to the customary rice and salted vegetables, steamed fish and eggs, and square rice cakes filled with vegetables.

She directed most of her conversation to their young guest, and her manner held an admirable balance between subservience to him as a person of imperial descent and motherly, or grandmotherly, warmth towards the orphaned child.

The boy accepted this as no more than his due, but had the good manners to compliment her on the food and the appointments of his quarters. He showed similar poise in chatting with Akitada's sisters, who responded with monosyllables and subdued giggles. Everything considered, the evening was a success, and Lady Sugawara was charmed.

After everybody had withdrawn for the night, Akitada checked all the gates and informed Seimei of the situation. Typically the old man had a comfortable saying to fit the situation.

"Virtue does not live alone," he said, when Akitada stressed the fact that Sakanoue could easily hire enough villains to overcome them and take or kill the boy. "It will always have neighbors. Do not worry! We shall find supporters." Also typically, he announced that he would keep watch all night outside the wing which housed the Sugawara ladies. Akitada decided to wait for Tora in the front courtyard.

It was a very dark night. The heat had lifted only slightly, and the stone of the well-coping against which Akitada was leaning was almost uncomfortably warm. All remained quiet. Finally, soon after a watchman had cried out the hour of the rat, there were footsteps, and then Tora's voice. Akitada went to open the gate.

The two men with Tora, seen indistinctly in the lantern light, seemed ordinary enough. They bowed politely, and the military looking fellow gave his name as Hitomaro, while the muscular man in the old monk's robe said he was Genba. Leaving Tora behind to guard the gate, Akitada led them to his room.

They sat down, looking appreciatively about at the books and calligraphy scrolls. The light was better here. Akitada saw two men of about his age, both fairly tall and well-built. Hitomaro, sunburnt and bearded, held himself stiffly at attention and his clothes and general appearance were clean and trim. He met Akitada's eyes with unsmiling directness. Genba, round-faced and clean shaven, but with a hard, muscular body, smiled broadly. He was not precisely neat, but his face was surprisingly gentle. Both bore Akitada's examination without protest or impatience.

Finally Akitada said, "Tora will have explained to you that we need your services for a few days only." They nodded in unison. "Has he explained your duties?" They shook their heads. "You will keep watch around the clock, but particularly during the night. You will be given a place to sleep during the daytime when you can be relieved, also three meals and fifty coppers a day to share between you. Are those terms agreeable?"

The man called Hitomaro said quietly, "We accept."

"The fact is," added Genba enthusiastically, "we are very glad for the generous offer. We would have done it for food alone."

Akitada regarded him more closely. He was suspicious of such eagerness, but Genba met his scrutiny with bland cheerfulness and both men had the resolute expressions of having nothing to lose. So he said, "You are very honest, but I prefer to pay. I hope there won't be any trouble, but you must remain alert. Should something happen that you cannot handle, you may raise a general alarm. Your duty begins immediately." He prepared to rise, but Hitomaro cleared his throat.

"May we know what we are guarding?" he asked. "Tora did not specify."

"This property. That is all you need to know."

"As you wish. But I must point out that we can deploy our strength to better advantage and develop a plan of operation if we are at least informed where the valuable object is located."

"There is no object. You are guarding my family."

"Ah! From whom?"

Akitada rose impatiently. "Enough! You will arm yourselves and patrol the walls around the clock."

The two men also stood, but Hitomaro remarked, "It is said there are robbers on every road and rats in every house. May we assume that your servants are loyal?"

Akitada fumed. "Of course. Tora you have already met. My secretary Seimei will speak to you shortly. He has served this family since before I was born. You may discuss the rest of the staff with him."

They bowed and left. A few minutes later Tora slipped in. "Well, what do you think?" he asked, looking at Akitada anxiously.

Akitada sighed. He felt tired. Pulling at the neck of his robe, uncomfortably moist from the heat, he said, "We will have to hope for the best. The fellow Genba looks a bit too happy for my taste, but at least he appears to be honest. He told me they would have worked for food. But he is certainly no monk, for he did not object to arming himself. Now go and keep an eye on them, while I get some rest."

The night passed uneventfully. Akitada rose before dawn to take over from Tora. His two new employees seemed competent, appearing at regular intervals on their patrol. Hitomaro looked surprised to see Akitada, but said nothing. Genba, however, paused occasionally to exchange a few words. Akitada encouraged this. The "monk" seemed curious about various sports, especially the annual wrestling matches for the emperor. But when Akitada, on his part, asked questions about Genba's background or that of his companion, he became evasive. He made few references to their past, and these entailed mostly humorous anecdotes about street characters and reminiscences of memorable meals. When Akitada became insistent, Genba departed on another round to check out a suspicious noise.

The sun rose on another cloudless sky. The daylight brought relative safety; attacks were highly unlikely at this time. Akitada told his two watchers to get some food and rest.

"Food!" Genba's face split into a joyous smile, and he trotted off eagerly in the direction of the kitchen, passing on the way the small figure of Sadamu, barefoot and in his white silk under-robe.

"Good morning, sir," the boy cried to Akitada. "What a fine day! Tora and I are making stilts today. Will you join us?"

"Perhaps later," said Akitada, tousling the boy's sleep-rumpled hair. His mother would be upset, but that could not be helped. He had more important errands today than walking about on stilts or playing football. Sadamu, at any rate, did not seem too disappointed. He waved and disappeared again.

The soldierly Hitomaro had gone to the well to wash his face and hands. He now sauntered back, casting a look around as the first rays of the sun gilded the tops of trees. Suddenly he gave an exclamation.

Walking quickly to Akitada, he said, "Look, sir! Over there! See that tall pine in the grove of trees? There's someone in it."

Akitada peered. The distance was too great to be certain. "I don't see anyone," he said.

Hitomaro shaded his eyes. "No. He's gone. But I swear I saw a small man for just a moment."

"Well," said Akitada, "even if someone climbed the tree, he need not have any designs on us. Go get some rest. Tora and the others will be up shortly."

Relieved that the night had passed peacefully, Akitada went to bathe and change into formal attire before paying his calls on Prince Yoakira's friends.

Lord Abe's mansion was closest to the Sugawara residence. Akitada identified himself and was shown into a shady garden. An elderly man stood by a small fishpond, tossing bits of rice dumpling into the water. He had laid Akitada's card on the edge of the veranda nearby and glanced toward it when Akitada made his bow.

"Ah, hmm," he said, returning the bow. "Yes, er . . . Sado . . . Mura . . . what was it again?" He started towards the card on the veranda, when Akitada guessed at his problem.

"I am Sugawara, sir. Sugawara Akitada."

"Oh, of course. Sugawara. I had it on the tip of my tongue. Any relation of . . . no,probably not. And what was it that we were to discuss?"

"Prince Yoakira's grandson has asked me to look into his grandfather's disappearance. I hoped that you might give me your observations of what happened at the Ninna temple."

Abe's face broke into a smile. "The Ninna temple? Now there is a fine place! I remember it well. So many beautiful halls near the mountains! We enjoyed the most delicious plums there! The monks grow them themselves, you know. Ah, I must go there again some time. Since you want my views, I can recommend it highly. An absolutely wonderful place if you need a cure. I have trouble with my eyes." He leaned forward to peer at Akitada more closely and said, "Spots!"

An awful suspicion seized Akitada. "Do you recall Prince Yoakira?" he asked.

"Yoakira?" Abe smiled and clapped his hands. "So you come from Yoakira! How is the old fellow? I haven't seen him for ages." He paused, frowning. "What was it we were talking about?"

"I am afraid . . ."began Akitada, but Abe was peering into the fish-pond. "Come, my little ones," he crooned. "Here's something good for you."

Akitada said loudly, "It has been a pleasure, sir. Many thanks for your excellent comments."

Abe looked up, smiled and waved a hand, "Not at all! Delightful! Er . . . Yoshida."

Akitada bowed and left. Poor old man. Even if he had still been in his right mind when the tragedy happened, he had no memory of it now. But a blissful loss of painful memories was perhaps the greatest gift of all, Akitada thought, as his eyes fell on some late blooming hollyhocks near the garden gate. His hand went to his temple where Tamako's fingers and sleeve had brushed his skin as she fastened the blooms to his hat.

He attempted to see the retired General Soga next. But one of the general's servants informed him that his master had left the city for the cooler shores of Lake Biwa where he had a summer villa, and Akitada turned his steps to the house of Lord Yanagida.

There was nothing at all wrong with Lord Yanagida's recall of the last time he saw his friend. His problem was altogether different.

He received Akitada in a study which was primarily remarkable for the number of religious paintings on the walls and the presence of a small altar with a Buddha figure. Yanagida himself appeared to be an elderly version of this figure, having the same soft and fleshy physique, the same round features, clean shaven, heavy-lidded and smiling beatifically. He wore heavy silk robes vaguely resembling vestments and carried a rosary in one hand.

His lordship maintained a calm reserve until Akitada had been seated and given a cup of chilled fruit juice. But as soon as Akitada explained the boy's concerns about his grandfather's disappearance, Yanagida became alarmed.

"Disappearance?" he gasped, fluttering his hands, the rosary beads swinging wildly. "You mean to say that no one has told the child about the blessed miracle? You must explain the idea of transfiguration to him. It was the most profoundly moving experience of my life! To be a witness to such a reward for devotion! I count myself blessed just for being there myself, a living testimonial! But I suppose you know that, or you would not be here. Oh, it was the holiest moment." Yanagida closed his eyes and sighed deeply.

Akitada's heart fell, but he asked anyway, "It would be most kind of you, sir, if you could give me an account of the events preceding the, er, miracle, so I can report to young Lord Minamoto."

Yanagida nodded. "Certainly, certainly. Nothing could be easier or more joyful. The whole scene is imprinted on my mind! It was still dark when Yoakira entered the shrine– for it shall always be a holy shrine now– and began his devotions. We went to sit outside, our minds caught up in the myriad things of this fleeting world, until he recited the sutra. We all heard him clearly. He was superb, never faltering, never missing a single line! It was inspiring, absolutely inspiring!" Yanagida fell to reciting the lines himself, counting them off on the beads between his fingers.

At the first brief pause, Akitada asked quickly, "Did you yourself examine the hall immediately after the prince was . . . transfigured?"

Yanagida placed the palms of his hands together and bowed his head. "It was my privilege and my blessing," he said. "It was when I realized that my friend had transcended this prison of eternal rebirth that I made my vow. I am preparing to put away my worldly self and take the tonsure, serving as a simple monk in that holy place where my friend achieved salvation. You may tell the child that from me."

"But how did you know it was a miracle? Could he not have left somehow?"

Yanagida closed his eyes and seemed to fall into a trance. There was the slightest hint of a smile around his full lips.

Akitada stared at him suspiciously. He distrusted demonstrations of religious fervor and wondered if Yanagida was covering up something, if he could possibly even have been Sakanoue's accessory. But he put the thought aside quickly. Yanagida, like the other three friends of the prince, enjoyed an excellent reputation and could not have known Sakanoue very well. Another glance about the room convinced him that he was merely dealing with a religious fanatic. Either way he would not get any help here, and he got up.

Yanagida also got to his feet, smiled at Akitada, his round face suffused with joy, and turning towards the altar, prostrated himself before the image. He began to declaim in a loud voice, "Life is impermanent, subject by nature to birth and extinction. Praise be to Amitabha! Only when birth and extinction have been eliminated is the bliss of nothingness realized. Praise be to Amitabha! . . ."

Akitada tiptoed from the room and sought out the last member of Yoakira's entourage, Lord Shinoda.

Shinoda had escaped the midday heat by perching on the edge of a stone bridge in his garden and dangling his bare feet into the shallow stream below. He looked old and frail, with a thick head of white hair and a neatly trimmed white beard and mustache.

Akitada, seeing the unconventional occupation of the old man, was afraid that this friend of Yoakira's had also passed into his dotage. He found out quickly, however, that unlike Abe, Lord Shinoda was in full possession of all his faculties.

"So you're the boy's master," he said after Akitada had introduced himself and stated his business. He waved towards the space beside him and said, "Take off your shoes and socks and stick your feet in the water. It's much too hot for formalities."

Akitada obeyed meekly. The water was blessedly cool after the hot, dusty road outside.

"Glad to hear Sakanoue put the boy in the university," remarked Shinoda, catching a floating leaf with his toe and flipping it out of the water. "Much the best thing under the circumstances. The family was unsettled by this business." He shot Akitada a sharp glance from bright black eyes. "Are you sure you didn't come to satisfy your own curiosity? You have that reputation, you know."

Akitada flushed, startled that the old man had heard of him. He said, "To be frank, I did not believe the story of a miracle even before the boy asked me to find out what really happened. But I certainly did not put the idea in his head."

Shinoda's expression became veiled, his tone distant. "I cannot confirm your suspicions."

An ambiguous answer. Akitada tried to read the other man's mind. Shinoda was his last chance to find out the truth. "There are aspects of the incident which trouble me," he said tentatively.

Shinoda shot him another look. "Really? You will have to tell me what they are."

Akitada met his eyes. "I wondered why all of you assumed immediately that the prince was dead. Without a body, I would have thought a thorough search of the hall, the temple and the surrounding woods, as well as of the prince's various residences throughout the country was in order. Instead you announced almost immediately that the prince was no more."

Shinoda looked down into the water. "There was a search, but we knew he was dead."

Akitada stared at him. "Are you telling me that you found his corpse?"

Shimoda raised his eyes. "Certainly not," he snapped. "How could there have been a miracle if Yoakira had merely died in the middle of his sutra reading?"

"Then how—"

Shimoda said impatiently, "Trust me, young man, we had sufficient proof of death as well as of a miracle. Surely you don't think that we would trick His Majesty with some hocus-pocus?"

"Of course not, but . . ." Akitada realized belatedly that the emperor's sanction of the miraculous event would present an insurmountable obstacle to his investigation. Shinoda was not being merely abstruse or obstructive. He was reminding Akitada of the dangerous ground he was treading. But Shinoda and the others had seen something that convinced them of Yoakira's demise. He said, "I won't question the miracle, sir, but what did you find that proved to you Yoakira had passed from this life?"

Shinoda did not answer. He pulled his skinny legs from the water and started drying them with the hem of his robe.

Akitada put a hand on the older man's sleeve. "Please, sir. I am not asking out of idle curiosity. It is a matter of some urgency . . . of the child's safety. What did you find?"

Shinoda stood up and looked down at Akitada. "Young man," he said severely, "if I believed for one moment that what you hint at is true, I would hardly sit quietly in my garden soaking my feet. Since you appear to be one of those restless people who cannot leave well enough alone, you will no doubt look elsewhere. I wish you luck!"