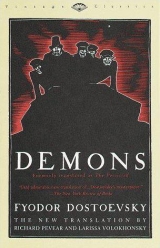

Текст книги "Demons"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 45 (всего у книги 56 страниц)

"You understand, Marie, you understand!" Shatov exclaimed. She was about to shake her head, but suddenly the same convulsion came over her. Again she hid her face in the pillow, and again for a whole minute she clung painfully, with all her might, to the hand of Shatov, who rushed to her and was out of his mind with terror.

"Marie, Marie! But this may be very serious, Marie!"

"Keep still... I don't want it, I don't want it," she kept exclaiming, almost in fury, turning her face up again, "don't you dare look at me with your compassion! Walk around, say something, talk..."

Shatov, like a lost man, tried to begin muttering something again.

"What do you do here?" she asked, interrupting him with squeamish impatience.

"I go to a merchant's office. You know, Marie, if I really wanted to, I could even get good money here."

"So much the better for you..."

"Ah, don't think anything, Marie, I just said it..."

"And what else are you doing? What are you preaching? Surely you can't help preaching, with such a character!"

"I preach God, Marie."

"In whom you don't believe yourself. That's an idea I never could understand."

"Let's drop it, Marie, save it for later."

"What was this Marya Timofeevna here?"

"That, too, we can save for later, Marie."

"Don't you dare make such remarks to me! Is it true that this death can be put down to these people's... villainy?"

"Absolutely true," Shatov ground out.

Marie suddenly raised her head and cried out painfully:

"Don't you dare say any more to me about it, ever, ever!"

And she fell back on the bed again in a seizure of the same convulsive pain; this was the third time now, but this time her moans grew louder, turned into cries.

"Oh, unbearable man! Oh, insufferable man!" she was thrashing about, no longer sparing herself, pushing away Shatov, who was standing over her.

"Marie, I'll do whatever you like... I'll walk, talk..."

"But can't you see it's begun?"

"What's begun, Marie?"

"How do I know. Do I know anything about it?... Oh, curse it! Oh, curse it all beforehand!"

"Marie, if you'd say what has begun... otherwise I... what am I to understand, then?"

"You're an abstract, useless babbler. Oh, curse everything in the world!"

"Marie! Marie!"

He seriously thought she was beginning to go mad.

"But can't you finally see that I'm in labor?" she raised herself a little, looking at him with a terrible, painful spite that distorted her whole face. "Curse it beforehand, this child!"

"Marie," Shatov exclaimed, realizing at last what it was about, "Marie... but why didn't you tell me sooner?" He suddenly collected himself and, with energetic determination, grabbed his cap.

"How did I know when I came in? Would I have come to you? I was told it would be another ten days! Where, where are you going, don't you dare!"

"To fetch a midwife! I'll sell my revolver; money's the first thing now!"

"Don't you dare do anything, no midwife, just some peasant woman, any old woman, I have eighty kopecks in my purse ... Village women give birth without midwives... And if I drop dead, so much the better..."

"You'll have both a midwife and a peasant woman. Only how, how can I leave you alone, Marie!"

But realizing that it was better to leave her alone now, despite all her frenzy, than leave her without help later on, he paid no attention to her moans and wrathful exclamations, and, trusting to his legs, started headlong down the stairs.

III

To Kirillov, first of all. It was already one o'clock in the morning. Kirillov was standing in the middle of the room.

"Kirillov, my wife's giving birth!"

"How's that?"

"Giving birth, to a baby!"

"You're not... mistaken?"

"Oh, no, no, she's having spasms! ... I need a woman, some old woman, right now... Can I get one now? You used to have lots of old women..."

"It's a great pity that I'm not able to give birth," Kirillov answered pensively, "that is, not that I'm not able to give birth, but that I'm not able to make it so that there is birth... or... No, I'm not able to say it."

"That is, you yourself can't help in childbirth; but that's not what I mean; a woman, an old woman, I'm asking for an old woman, a nurse, a servant!"

"You'll have an old woman, only maybe not now. If you like, instead, I'll..."

"Oh, impossible; I'll go right now to the Virginsky woman, the midwife."

"A harpy!"

"Oh, yes, Kirillov, yes, but she's the best one! Oh, yes, it will all be without awe, without joy, squeamish, with curses, with blasphemy– this great mystery, the appearance of a new being! ... Oh, she's already cursing it now! ..."

"If you wish, I..."

"No, no, but while I'm running around (oh, I'll drag that Virginsky woman here!), you should go to my stairway every once in a while and listen quietly, but don't you dare go in, you'll frighten her, don't go in for anything, only listen... just in some terrible case. Well, if something extreme happens, then go in."

"I understand. There's one more rouble. Here. I wanted a chicken for tomorrow, but no more. Run quickly, run as hard as you can. There's a samovar all night."

Kirillov knew nothing about the intentions concerning Shatov, and even before he never knew the full extent of the danger that threatened him. He knew only that he had some old scores with "those people," and though he himself was partly mixed up in the affair through some instructions conveyed to him from abroad (rather superficial ones, however, for he had never participated closely in anything), he had lately dropped everything, all assignments, removed himself completely from all affairs, and in the first place from the "common cause," and given himself to a life of contemplation. Although at the meeting Pyotr Verkhovensky had summoned Liputin to Kirillov's to make sure he would take the "Shatov case" upon himself at the proper moment, nevertheless, in his talk with Kirillov he did not say a word about Shatov, not even a hint—probably regarding it as impolitic, and Kirillov even as unreliable—and had left it till the next day, when everything would already be done, and it would therefore "make no difference" to Kirillov; so, at least, Pyotr Stepanovich's reasoning about Kirillov went. Liputin also noticed very well that, despite the promise, not a word was mentioned about Shatov, but Liputin was too agitated to protest.

Shatov ran like the wind to Muravyiny Street, cursing the distance and seeing no end to it.

It would take a lot of knocking at Virginsky's: everyone had long been asleep. But Shatov started banging on the shutters as hard as he could and without any ceremony. The dog tied in the yard strained and went off into a furious barking. All the dogs down the street joined in; a clamor of dogs arose.

"Why are you knocking and what is it you want?" the soft voice of Virginsky, quite incommensurate with the "outrage," came at last from a window. The shutter opened a bit, as did the vent.

"Who's there, what scoundrel?" the female voice of the old maid, Virginsky's relative, this time fully commensurate with the outrage, angrily shrieked.

"It's me, Shatov, my wife has come back to me and is now presently giving birth..."

"Well, let her! Away with you!"

"I've come for Arina Prokhorovna, I won't leave without Arina Prokhorovna!"

"She can't just go to everybody. Night practice is a separate thing ... Away with you to the Maksheev woman, and don't you dare make any more noise!" the irate female voice rattled on. One could hear Virginsky trying to stop her; but the old maid kept pushing him away and would not give in.

"I won't leave!" Shatov shouted again.

"Wait, wait!" Virginsky finally raised his voice, overpowering the maid. "I beg you, Shatov, wait five minutes, I'll wake up Arina Prokhorovna, and please don't knock or shout... Oh, how terrible this all is!"

After five endless minutes, Arina Prokhorovna appeared.

"Your wife has come to you?" her voice issued from the vent window and, to Shatov's surprise, was not at all angry, merely peremptory as usual; but Arina Prokhorovna could not speak any other way.

"Yes, my wife, and she's in labor."

"Marya Ignatievna?"

"Yes, Marya Ignatievna. Of course, Marya Ignatievna!"

Silence ensued. Shatov waited. There was whispering in the house.

"Did she come long ago?" Madame Virginsky asked again.

"Tonight, at eight o'clock. Please hurry."

Again there was whispering and again an apparent discussion.

"Listen, you're not mistaken, are you? Did she send for me herself?"

"No, she didn't send for you, she wants a woman, a peasant woman, so as not to burden me with the expense, but don't worry, I'll pay." "All right, I'll come, pay or no pay. I've always thought highly of Marya Ignatievna's independent feelings, though she may not remember me. Do you have the most necessary things?" "I have nothing, but I'll get it all, I will, I will..." "So there's magnanimity in these people, too!" Shatov thought, as he headed for Lyamshin's. "Convictions and the man—it seems they're two different things in many ways. Maybe in many ways I'm guilty before them! ... We're all guilty, we're all guilty, and ... if only we were all convinced of it! ..."

He did not have to knock long at Lyamshin's; surprisingly, the man instantly opened the window, having jumped out of bed barefoot, in his underwear, at the risk of catching cold—he who was so nervous and constantly worried about his health. But there was a particular reason for such sensitiveness and haste; Lyamshin had been trembling all night and was still so agitated that he could not sleep, as a consequence of the meeting of ourpeople; he kept imagining visits from some uninvited and altogether unwanted guests. The news about Shatov's denunciation tormented him most of all... And then suddenly, as if by design, there came such terrible, loud knocking at the window! ...

He got so scared when he saw Shatov that he immediately slammed the window and ran for his bed. Shatov started knocking and shouting furiously.

"How dare you knock like that in the middle of the night?" Lyamshin, though sinking with fear, shouted threateningly, venturing to open the window again after a good two minutes and making sure finally that Shatov had come alone.

"Here's your revolver; take it back, give me fifteen roubles." "What, are you drunk? This is hooliganism; I'll simply catch cold. Wait, let me throw a plaid over me."

"Give me fifteen roubles right now. If you don't, I'll knock and shout till dawn; I'll break your window."

"And I'll shout for help and you'll be locked up." "And I'm mute, am I? Do you think I won't shout for help? Who should be more afraid of shouting for help, you or me?"

"How can you nurse such mean convictions ... I know what you're hinting at. . . Wait, wait, for God's sake, don't knock! Good heavens, who has money at night? What do you need money for, if you're not drunk?"

"My wife has come back to me. I've chopped off ten roubles for you, I never once fired it; take the revolver, take it this minute."

Lyamshin mechanically reached his hand out the window and accepted the revolver; he waited a little, and all at once, quickly popping his head out the window, started babbling, as if forgetting himself, and with a chill in his spine:

"You're lying, your wife hasn't come back to you at all. It's... it's that you simply want to run away somewhere."

"You're a fool, where am I going to run to? Let your Pyotr Verkhovensky run away, not me. I just left the midwife Virginsky, and she agreed at once to come to me. Ask her. My wife's in labor; I need money; give me money!"

A whole fireworks of ideas flashed in Lyamshin's shifty mind. Everything suddenly took a different turn, yet fear still prevented him from reasoning.

"But how... aren't you separated from your wife?"

"I'll smash your head in for such questions."

"Ah, my God, forgive me, I understand, it's just that I was flabbergasted... But I understand, I understand. But... but—will Arina Prokhorovna really go? Didn't you just say she went? You know, that's not true. See, see, see, at every step you say things that aren't true."

"She must be with my wife now, don't keep me, it's not my fault that you're so stupid."

"That's not true, I'm not stupid. Excuse me, I really can't..."

And, completely at a loss now, he started to close the window for the third time, but Shatov raised such a cry that he immediately stuck himself out again.

"But this is a total infringement upon a person! What are you demanding of me, well, what, what?—formulate it! And in the middle of the night, note that, note that!"

"I'm demanding fifteen roubles, muttonhead!"

"But maybe I don't wish to take the revolver back. You have no right. You bought the thing—and that's that, and you have no right. There's no way I can produce such a sum at night. Where can I get such a sum?"

"You always have money; I've taken off ten roubles for you, but you're a notorious little Jew."

"Come the day after tomorrow—do you hear, the day after tomorrow, in the morning, at twelve sharp, and I'll give you all of it, agreed?"

Shatov knocked furiously at the window for the third time:

"Give me ten roubles, and five tomorrow at daybreak."

"No, five the day after tomorrow, and tomorrow nothing, by God. You'd better not come, you'd better not come."

"Give me ten—oh, you scoundrel!"

"Why such abuse? Wait, I need a light; look, you've broken the window... Why such abuse in the night? Here!" he held a note out to him through the window.

Shatov grabbed the note—it was five roubles.

"By God, I can't, strike me dead, but I can't, the day after tomorrow I can give you all of it, but nothing now."

"I won't leave!" Shatov bellowed.

"Well, here, take more, you see, more, and that's it. You can shout your head off, I won't give you more, whatever happens, I won't, I won't, I won't!"

He was in a frenzy, in despair, covered with sweat. The two notes he had added were for a rouble each. Altogether, Shatov had collected seven roubles.

"Well, devil take you, I'll come tomorrow. I'll give you a beating, Lyamshin, if you haven't got eight roubles ready."

"And I won't be home, you fool!" Lyamshin thought to himself quickly.

"Wait, wait!" he called frenziedly after Shatov, who was already running off. "Wait, come back. Tell me, please, is it true what you said about your wife coming back to you?"

"Fool!" Shatov spat and ran home as hard as he could.

IV

I will note that Arina Prokhorovna knew nothing about the intentions adopted at the previous day's meeting. Virginsky, coming home stunned and weakened, did not dare tell her the adopted decision; but even so he could not help himself and did reveal half—that is, all that Verkhovensky had reported to them about Shatov's definite intention to denounce them; but he declared at the same time that he did not quite trust this report. Arina Prokhorovna was terribly frightened. That was why, when Shatov came running to fetch her, she immediately decided to go, tired though she was from having toiled over a woman in childbirth all the night before. She had always been sure that "such trash as Shatov was capable of civic meanness"; yet the arrival of Marya Ignatievna placed the matter in a new perspective. Shatov's fright, the desperate tone of his appeals, his pleas for help, signified a turnabout in the traitor's feelings: a man who had even resolved to betray himself just so as to ruin others would, it seemed, have a different look and tone than the reality presented. In short, Arina Prokhorovna resolved to examine it all herself, with her own eyes. Virginsky remained very pleased with her resolution—as if five tons had been lifted from him! A hope was even born in him: Shatov's look seemed to him to the highest degree incompatible with Verkhovensky's supposition ...

Shatov was not mistaken; on his return he found Arina Prokhorovna already with Marie. She had just arrived, had disdainfully chased away Kirillov, who was sticking about at the foot of the stairs; had hastily made the acquaintance of Marie, who did not recognize her as an old acquaintance; had found her "in a very bad state"—that is, angry, upset, and in "the most fainthearted despair"—and in some five minutes had decidedly gained the upper hand over all her objections.

"What's all this carping about not wanting an expensive midwife?" she was saying the very moment Shatov entered. "Sheer nonsense, false notions, from the abnormal state you're in. You'd have fifty chances of ending badly with the help of some simple old woman, some peasant granny; and then there'd be more troubles and costs than with an expensive midwife. How do you know I'm an expensive midwife? You can pay later, I won't take too much from you, and I guarantee you success; with me you won't die, I've seen lots worse cases. And I'll send the baby to the orphanage, tomorrow even, if you like, and then to the country to be brought up, and that'll be the end of that. Then you can recover, settle down to some rational work, and in a very short time reward Shatov for the lodging and expenses, which won't be all that great..."

"It's not that ... I have no right to be a burden..."

"Rational and civic feelings, but, believe me, Shatov will spend almost nothing, if he decides to turn himself, at least a little, from a fantastic gentleman into a man of right ideas. All he has to do is not commit any follies, not beat the drum, not run around town with his tongue hanging out. If he's not tied down, he'll rouse all the doctors in town before morning; he certainly roused all the dogs on my street. There's no need for doctors, I've already said I guarantee everything. You could maybe hire an old woman to serve you, that won't cost anything. Though he himself could be of use for something besides just foolishness. He's got arms, he's got legs, he can run over to the pharmacy without insulting your feelings in any way by his charity. The devil it's charity! Isn't he the one who got you into this state? Wasn't it he who made you quarrel with the family where you were governess, with the egoistic purpose of marrying you? We heard about that... Though he himself just came running like a lunatic and shouting for the whole street to hear. I'm not forcing myself on anybody, I came solely for you, on the principle that our people are all bound by solidarity; I announced that to him before I left the house. If I'm unnecessary in your opinion, then good-bye; only you may be asking for trouble that could easily be avoided."

And she even got up from her chair.

Marie was so helpless, she was suffering so much, and, to tell the truth, was so afraid of what lay ahead of her, that she did not dare let her go. But the woman suddenly became hateful to her: what she was saying was not it, was not at all what was in Marie's soul! But the prophecy of possible death at the hands of an inexperienced midwife overcame her revulsion. To make up for it, she became, from that moment on, even more exacting, more merciless to Shatov. It finally reached a point where she forbade him not only to look at her but even to stand facing her. The pains were becoming worse. The curses and even profanities were becoming more violent.

"Eh, why don't we send him out," Arina Prokhorovna snapped, "he looks awful, he just frightens you, he's pale as a corpse! What is it to you, tell me please, you funny fellow? What a comedy!"

Shatov did not reply; he resolved not to reply.

"I've seen foolish fathers on such occasions; they, too, lose their minds. But at least they..."

"Stop it, or leave me and let me die! Nobody say a word! I don't want it, I don't want it!" Marie started shouting.

"It's impossible not to say a word, or are you out of your mind yourself? That's how I understand you in the state you're in. We have to talk business at least: tell me, do you have anything ready? You answer, Shatov, she can't be bothered with it."

"Tell me what precisely is necessary?"

"In other words, nothing's ready."

She counted off all the needful things necessary and, one must do her justice, limited herself to sheer necessities, to beggarliness. It turned out that Shatov had some things. Marie took her key and gave it to him to look in her bag. His hands were trembling and he fumbled somewhat longer than he should have in opening the unfamiliar lock. Marie lost her temper, but when Arina Prokhorovna ran to take the key from him, she refused to let her peek into the bag, and insisted with capricious cries and tears that the only one who should open the bag was Shatov.

For certain things he had to run over to Kirillov. As soon as Shatov turned to go, she immediately began calling him back frenziedly, and calmed down only when Shatov rushed madly back from the stairs and explained to her that he was leaving only for a minute, to get the most necessary things, and would come back at once.

"Well, lady, you're a hard one to please," Arina Prokhorovna laughed. "One minute he has to stand facing the wall and not dare look at you, the next he mustn't dare leave for a moment or you'll cry. He might think something this way. Now, now, don't be capricious, don't pout, I'm just laughing."

"He dare not think anything."

"Tsk, tsk, tsk, if he wasn't in love with you like a sheep, he wouldn't be running around town with his tongue hanging out, and he wouldn't have roused all the local dogs. He broke my window."

V

Shatov found Kirillov, who was still pacing his room from corner to corner, so distracted that he had even forgotten about the wife's arrival and listened uncomprehendingly.

"Ah, yes," he remembered suddenly, as if tearing himself away with effort, and only for a moment, from some idea that held him fascinated, "yes ... an old woman ... A wife or an old woman? Wait: both a wife and an old woman, right? I remember; I went; the old woman will come, only not now. Take the pillow. Anything else? Yes... Wait, Shatov, do you ever have moments of eternal harmony?"

"You know, Kirillov, you mustn't go on not sleeping at night."

Kirillov came to himself and—strangely—began to speak even far more coherently than he usually spoke; one could see that he had long been formulating it all, and perhaps had written it down:

"There are seconds, they come only five or six at a time, and you suddenly feel the presence of eternal harmony, fully achieved. It is nothing earthly; not that it's heavenly, but man cannot endure it in his earthly state. One must change physically or die. The feeling is clear and indisputable. As if you suddenly sense the whole of nature and suddenly say: yes, this is true. [191]God, when he was creating the world, said at the end of each day of creation: 'Yes, this is true, this is good.' [192] This... this is not tenderheartedness, but simply joy. You don't forgive anything, because there's no longer anything to forgive. You don't really love—oh, what is here is higher than love! What's most frightening is that it's so terribly clear, and there's such joy. If it were longer than five seconds—the soul couldn't endure it and would vanish. In those five seconds I live my life through, and for them I would give my whole life, because it's worth it. To endure ten seconds one would have to change physically. I think man should stop giving birth. Why children, why development, if the goal has been achieved? It's said in the Gospel that in the resurrection there will be no birth, but people will be like God's angels. [193]A hint. Your wife's giving birth?"

"Kirillov, does it come often?"

"Once in three days, once a week."

"You don't have the falling sickness?"

"No."

"Then you will. Watch out, Kirillov, I've heard that this is precisely how the falling sickness starts. An epileptic described to me in detail this preliminary sensation before a fit, exactly like yours; he, too, gave it five seconds and said it couldn't be endured longer. Remember Muhammad's jug that had no time to spill while he flew all over paradise on his horse? [194]The jug is those same five seconds; it's all too much like your harmony, and Muhammad was an epileptic. Watch out, Kirillov, it's the falling sickness!"

"It won't have time," Kirillov chuckled softly.

VI

The night was passing. Shatov was sent out, abused, called back. Marie reached the last degree of fear for her life. She shouted that she wanted to live, that "she must live, she must!" and was afraid to die. "Not that, not that!" she kept repeating. Had it not been for Arina Prokhorovna, things would have been very bad. Gradually she gained complete control over the patient, who started obeying her every word, her every bark, like a child. Arina Prokhorovna used severity, not kindness, but her work was masterful. Dawn broke. Arina Prokhorovna suddenly came up with the idea that Shatov had just run out to the stairs to pray to God, and she began to laugh. Marie also laughed, spitefully, caustically, as if it made her feel better. Finally, they chased Shatov out altogether. A damp, cold morning came. He leaned his face to the wall in the corner, exactly as the evening before when Erkel came. He was trembling like a leaf, afraid to think, yet his thought clung to everything that presented itself to his mind, as happens in dreams. Reveries incessantly carried him away, and incessantly snapped off like rotten threads. Finally, it was no longer groans that came from the room, but terrible, purely animal sounds, intolerable, impossible. He wanted to stop his ears, but could not, and fell to his knees, unconsciously repeating "Marie, Marie!" And then, finally, there came a cry, a new cry, at which Shatov gave a start and jumped up from his knees, the cry of an infant, weak, cracked. He crossed himself and rushed into the room. In Arina Prokhorovna's hands a small, red, wrinkled being was crying and waving its tiny arms and legs, a terribly helpless being, like a speck of dust at the mercy of the first puff of wind, yet crying and proclaiming itself, as if it, too, somehow had the fullest right to life... Marie was lying as if unconscious, but after a minute she opened her eyes and gave Shatov a strange, strange look: it was somehow quite a new look, precisely how he was as yet unable to understand, but he did not know or remember her ever having such a look before.

"A boy? A boy?" she asked Arina Prokhorovna in a pained voice.

"A little boy!" she shouted in reply, swaddling the baby.

For a moment, once she had swaddled him and before laying him across the bed between two pillows, she handed him to Shatov to hold. Marie, somehow on the sly and as if she were afraid of Arina Prokhorovna, nodded to him. He understood at once and brought the baby over to show her.

"How... pretty..." she whispered weakly, with a smile.

"Pah, what a look!" the triumphant Arina Prokhorovna laughed merrily, peeking into Shatov's face. "Just see the face on him!"

"Be glad, Arina Prokhorovna... This is a great joy..." Shatov babbled with an idiotically blissful look, radiant after Marie's two words about the baby.

"What's this great joy of yours?" Arina Prokhorovna was amusing herself, while bustling about, tidying up, and working like a galley slave.

"The mystery of the appearance of a new being, a great mystery and an inexplicable one, Arina Prokhorovna, and what a pity you don't understand it!"

Shatov was muttering incoherently, dazedly, and rapturously. It was as if something were swaying in his head, and of itself, without his will, pouring from his soul.

"There were two, and suddenly there's a third human being, a new spirit, whole, finished, such as doesn't come from human hands; a new thought and a new love, it's even frightening ... And there's nothing higher in the world!"

"A nice lot of drivel! It's simply the further development of the organism, there's nothing to it, no mystery," Arina Prokhorovna was guffawing sincerely and merrily. "That way every fly is a mystery. But I tell you what: unnecessary people shouldn't be born. First reforge everything so that they're not unnecessary, and then give birth to them. Otherwise, you see, I've got to drag him to the orphanage tomorrow... Though that's as it should be."

"Never will he go from me to the orphanage!" Shatov said firmly, staring at the floor.

"You're adopting him?"

"He is my son."

"Of course, he's a Shatov, legally he's a Shatov, and there's no point presenting yourself as a benefactor of mankind. They just can't do without their phrases. Well, well, all right, only I tell you what, ladies and gentlemen," she finally finished tidying up, "it's time for me to go. I'll come again in the morning, and in the evening if need be, and now, since it's all gone off so very well, I must also run to the others, they've been waiting a long time. Shatov, you've got an old woman sitting somewhere; the old woman is fine, but you, dear husband, don't you leave her either; stay by her, just in case you can be useful; and I don't suppose Marya Ignatievna will chase you away... well, well, I'm just laughing..."

At the gate, where Shatov went to see her off, she added, to him alone:

"You've made me laugh for the rest of my life: I won't take any money from you; I'll laugh in my sleep. I've never seen anything funnier than you last night."

She left thoroughly pleased. From Shatov's look and his talk, it became clear as day that the man "was going to make a father of himself, and was a consummate dishrag." She ran over to her place, though it would have been closer to go directly to her next patient, on purpose to tell Virginsky about it.

"Marie, she said you should wait and not sleep for a while, though that, I see, is terribly difficult. . ." Shatov began timidly. "I'll sit here by the window and keep watch on you, hm?"

And he sat down by the window behind the sofa so that there was no way she could see him. But before a minute had passed, she called him and squeamishly asked him to straighten her pillow. He began to straighten it. She was looking angrily at the wall.

"Not like that, oh, not like that... What hands!"

Shatov straightened it again.

"Bend down to me," she suddenly said wildly, trying all she could not to look at him.