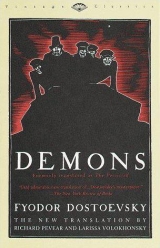

Текст книги "Demons"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 36 (всего у книги 56 страниц)

Part Three

1: The Fête. First Part

I

The fête took place, all the perplexities of the previous "Shpigulin" day notwithstanding. I think that even if Lembke had died that same night, the fête would still have taken place in the morning—so much of some special significance did Yulia Mikhailovna connect with it. Alas, until the final moment she remained blind and did not understand the mood of society. No one towards the end believed that the great day would go by without some colossal adventure, without a "denouement," as some put it, rubbing their hands in anticipation. Many, it is true, tried to assume a most frowning and political look; but, generally speaking, the Russian man is boundlessly amused by any socially scandalous commotion. True, there was among us something rather more serious than the mere thirst for scandal; there was a general irritation, something unappeasably spiteful; it seemed everyone was terribly sick of everything. Some sort of general, muddled cynicism had come to reign, a forced, as if strained, cynicism. Only the ladies were not to be muddled, and that only on one point: their merciless hatred of Yulia Mikhailovna. In this all the ladies' tendencies converged. And she, poor woman, did not even suspect; until the final hour she remained convinced that she was "surrounded" and still the subject of "fanatical devotion."

I have already hinted at the fact that various trashy sorts of people had appeared among us. Always and everywhere, in a troubled time of hesitation or transition, various trashy sorts appear. I am not speaking of the so-called "vanguard," who always rush ahead of everyone else (their chief concern) and whose goal, though very often quite stupid, is still more or less definite. No, I am speaking only of scum. This scum, which exists in every society, rises to the surface in any transitional time, and not only has no goal, but has not even the inkling of an idea, and itself merely expresses anxiety and impatience with all its might. And yet this scum, without knowing it, almost always falls under the command of that small group of the "vanguard" which acts with a definite goal, and which directs all this rabble wherever it pleases, provided it does not consist of perfect idiots itself—which, incidentally, also happens. It is said among us now, when everything is already over, that Pyotr Stepanovich was controlled by the Internationale, [165]that Pyotr Stepanovich controlled Yulia Mikhailovna, and that she, at his command, directed all sorts of scum. Our most solid minds are now marveling at themselves: how could they suddenly have gone so amiss then? What our troubled time consisted of, and from what to what our transition was—I do not know, and no one, I think, knows—except perhaps certain visitors from outside. And yet the trashiest people suddenly gained predominance and began loudly criticizing all that's holy, whereas earlier they had not dared to open their mouths, and the foremost people, who until then had so happily kept the upper hand, suddenly began listening to them, and became silent themselves; and some even chuckled along in a most disgraceful way. Some sort of Lyamshins, Telyatnikovs, landowner Tentetnikovs, homegrown milksop Radishchevs, [166]little Jews with mournful but haughty smiles, jolly passing travelers, poets with a tendency from the capital, poets who in place of a tendency and talent had peasant coats and tarred boots, majors and colonels who laughed at the meaninglessness of their rank and were ready, for an extra rouble, to take off their swords at once and slink away to become railroad clerks; generals defecting to the lawyers; developed dealers, developing little merchants, countless seminarians, women who embodied in themselves the woman question—all this suddenly and fully gained the upper hand among us, and over whom? Over the club, over venerable dignitaries, over generals on wooden legs, over our most strict and inaccessible ladies' society. If even Varvara Petrovna, right up to the catastrophe with her boy, was all but running errands for all this scum, then some of our Minervas can be partially forgiven for their befuddlement at the time. Now everything is imputed, as I have already said, to the Internationale. The idea has grown so strong that even all the visiting outsiders have been informed along these lines. Just recently Councillor Kubrikov, sixty-two years old and with a Stanislav round his neck, [167] came without any summons and declared in a heartfelt voice that during the whole three months he had undoubtedly been under the influence of the Internationale. And when, with all due respect for his age and merits, he was asked to explain himself more satisfactorily, though unable to present any documents except that he "felt it with all his senses," he nevertheless stuck firmly to his declaration, so that he was not questioned further.

I will repeat once again. Among us there was also preserved a small group of prudent persons who had secluded themselves at the very beginning and even locked themselves in. But what lock can stand against a law of nature? In the same way, even in the most prudent families, young ladies grow up who have a need to go dancing. And so all these persons, too, ended up by subscribing for the governesses. And the ball promised to be so magnificent, boundless; wonders were being told; rumors spread about visiting princes with lorgnettes, about ten ushers, all young cavaliers, with bows on their left shoulders; about Petersburg movers of some sort; about Karmazinov consenting to augment the collection by reading Merciin the costume of a governess from our province; about the planned "quadrille of literature," also all in costume, with each costume representing some tendency. Finally, also in costume, some sort of "honest Russian thought" would perform a dance—which in itself was a complete novelty. How could one not subscribe? Everyone subscribed.

II

According to the program, the festive day was divided into two parts: the literary matinée, from noon till four, and then the ball, from nine o'clock on through the night. But this arrangement itself concealed germs of disorder. First, from the very beginning a rumor established itself among the public about a luncheon right after the literary matinée, or even during it, with a break especially arranged for that purpose—a free luncheon, naturally, as part of the program, and with champagne. The enormous price of the ticket (three roubles) contributed to this rumor's taking root. "Because why should I subscribe for nothing? The fête is supposed to go on round the clock, so they'll have to feed us. People will get hungry"—thus the reasoning went. I must admit that it was Yulia Mikhailovna herself who planted this pernicious rumor through her own light-mindedness. About a month earlier, still under the initial enchantment of the grand design, she had babbled about her fête with whoever happened along, and about the fact that toasts would be proposed she had even sent a notice to one of the metropolitan newspapers. She had been seduced mainly by these toasts then: she wanted to propose them herself, and kept devising them in anticipation. They were to explain our chief banner (what banner? I bet the poor dear never devised anything), to be passed on in the form of reports to the metropolitan newspapers, to touch and charm the higher authorities, and then to go winging over all the provinces, arousing astonishment and imitation. But for toasts champagne was necessary, and since one could not really drink champagne on an empty stomach, a luncheon, of itself, also became necessary. Later, when through her efforts a committee had been formed and they got down to business more seriously, it was proved to her at once and clearly that if one were dreaming of banquets, very little would be left for the governesses, even with the most abundant collection. The question thus presented two solutions: either a Belshazzar's feast [168]with toasts and about ninety roubles left for the governesses, or the realization of a significant collection, with the fête being, so to speak, only for form. The committee only wanted to give her a scare, however, and, of course, came up with a third solution, conciliatory and sensible—that is, quite a proper fête in all respects, only without champagne, and thus with quite a decent sum as a balance, much more than ninety roubles. But Yulia Mikhailovna did not agree; her character despised the philistine middle. She resolved then and there, since the first idea was unfeasible, to rush immediately and entirely to the opposite extreme—that is, to realize a colossal collection that would be the envy of all the provinces. "For the public must finally understand," she concluded her fiery committee speech, "that the achievement of universal human goals is incomparably loftier than momentary physical pleasures, that the fête is essentially only a proclamation of the great idea, and therefore one must be content with the most economical little German ball, solely as an allegory, since it's impossible to do without this obnoxious ball altogether!"—so much did she suddenly hate it. But she was finally calmed down. It was then, for example, that they thought up and suggested the "quadrille of literature" and other aesthetic things to replace physical pleasures. It was then, too, that Karmazinov finally agreed to read Merci(until then he had only hemmed and hawed), and thereby annihilate even the very idea of food in the minds of our incontinent public. In this way the ball was again becoming a most magnificent festivity, though no longer of the same sort. And so as not to go soaring off completely into the clouds, it was decided that at the beginning of the ball they would serve tea with lemon and little round cookies, then orgeat and lemonade, and lastly even ice cream, but that was all. For those who, always and everywhere, inevitably feel hungry and, above all, thirsty—a special buffet would be opened at the far end of the suite of rooms, to be taken charge of by Prokhorych (the head cook at the club), who—though under strict supervision by the committee—would serve whatever anyone liked, but for a separate price, and to that end a written announcement would be posted at the door of the reception hall that the buffet was outside the program. But for the matinée they decided not to open the buffet at all, so as not to interfere with the reading, even though the buffet would be located five rooms away from the white hall in which Karmazinov had consented to read Merci.Curiously, it seems this event—that is, the reading of Merci—was seen by the committee as being all too colossally significant, and even by the most practical people. As for the more poetical people, the wife of the marshal of nobility announced to Karmazinov, for instance, that after the reading she would at once order a marble plaque to be fixed to the wall of her white hall with an inscription in gold saying that on such-and-such a day and year, here, on this spot, the great Russian and European writer, as he laid down his pen, read Merciand thus for the first time bade farewell to the Russian public in the persons of the representatives of our town, and that everyone would be able to read this inscription at the ball, that is, only five hours after Merciwas read. I know for certain that it was chiefly Karmazinov who demanded that there be no buffet at the matinée, while he was reading, on any account whatsoever, despite the remarks of some committee members that this was not quite our way of doing things.

Thus matters stood, while in town people still went on believing in a Belshazzar's feast—that is, in the committee buffet; they believed in it to the last hour. Even the young ladies dreamed of quantities of candies and preserves and other unheard-of things. Everyone knew that the collection realized was abundant, that the whole town would be storming the doors, that people were coming in from the country, and there were not enough tickets. It was also known that beyond the fixed price there had also been considerable donations: Varvara Petrovna, for example, had paid three hundred roubles for her ticket and provided all the flowers from her greenhouse to decorate the hall. The marshal's wife (a committee member) provided her house and the lighting; the club provided the music and servants, and released Prokhorych for the whole day. There were other donations, though not such big ones, so that there was even a thought of lowering the original ticket price from three roubles to two. The committee indeed feared at first that the young ladies would not come for three roubles, and suggested arranging family tickets somehow—namely, by asking each family to pay for just one young lady, while all other young ladies of the same name, even an edition of ten, would come free. But all fears proved groundless: on the contrary, it was precisely the young ladies who did come. Even the poorest officials brought their girls, and it was only too clear that if they had not had girls, it would never have occurred to them to subscribe. One most insignificant secretary brought all seven of his daughters, not to mention his wife, of course, and also his niece, and each of these persons held a three-rouble entrance ticket in her hand. One can imagine, however, what a revolution went on in town! Take merely the fact that the fête was divided into two parts, and thus for each lady two costumes were necessary—a morning gown for the reading, and a ball gown for the dancing. Many of the middle class, it turned out later, pawned everything for that day, even the family linen, even their sheets and almost their mattresses, to the local Jews, who, over the past two years, as if on purpose, had been settling in terrible quantities in our town, and keep coming more and more. Almost all the officials took an advance on their salaries, and some landowners sold much-needed cattle, and all this just so as to bring their young ladies looking like real marquises, and to be no worse than others. The magnificence of the costumes this time was, considering the place, unheard-of. Two weeks beforehand the town was already stuffed with family anecdotes, all of which were immediately carried to Yulia Mikhailovna's court by our witlings. Family caricatures were passed around. I myself saw several drawings of this sort in Yulia Mikhailovna's album. All this became only too well known there where the anecdotes originated; that, it seems to me, is why such hatred for Yulia Mikhailovna had built up lately in these families. Now they all curse and gnash their teeth when they recall it. But it was clear beforehand that if the committee should fail to please in some way, were the ball to go amiss somehow, there would be an unheard-of outburst of indignation. That is why everyone was secretly expecting a scandal; and if it was so expected, how then could it not take place? At noon precisely the orchestra struck up. Being one of the ushers, that is, one of the twelve "young men with a bow," I saw with my own eyes how this day of infamous memory began. It began with a boundless crush at the entrance. How did it happen that everything went amiss from the very first, beginning with the police? I do not blame the real public: fathers of families not only were not crowding each other or anyone else, even despite their rank, but, on the contrary, are said to have been abashed while still in the street at the sight, unusual for our town, of the shoving mob that was besieging the entrance and trying to force it, instead of simply going in. Meanwhile, carriages kept driving up and finally blocked the street. Now, as I write, I have solid grounds for affirming that some of the vilest scum of our town were simply brought in without tickets by Lyamshin and Liputin, and perhaps also by someone else who, like me, was one of the ushers. Anyway, even completely unknown persons appeared, who came from other districts and elsewhere. The moment these savages entered the hall, they would go at once to inquire, in the same words (as if they had been prompted), where the buffet was, and on learning that there was no buffet, would begin swearing without any politics and with a boldness hitherto unusual among us. True, some of them came drunk.

Some were struck, like savages, by the magnificence of the marshal's wife's reception hall, since they had never seen anything like it, and, on entering, would become hushed for a moment and gaze around openmouthed. This big White Hall, despite its already decrepit structure, was indeed magnificent: of huge dimensions, with windows on both sides, with a ceiling decorated in the old manner and trimmed with gold, with galleries, with mirrors between the windows, with red and white draperies, with marble statues (such as they were, still they were statues), with heavy old furniture of the Napoleonic era, gilt white and upholstered in red velvet. At the moment described here, a high platform rose up at the end of the hall for the writers who were to read, and the entire room was completely filled with chairs, like the parterre of a theater, with wide aisles for the public. But after the first moments of astonishment, the most senseless questions and declarations would begin. "Maybe we don't even want any reading... We paid money... The public has been brazenly deceived... We're the masters, not the Lembkas! ..." In a word, as though it were for just this that they had been let in. I recall particularly one confrontation in which yesterday's visiting princeling distinguished himself, the one who had been at Yulia Mikhailovna's the previous morning, in his standing collar, and looking like a wooden doll. He, too, at her relentless request, had agreed to pin a bow to his left shoulder and become our fellow usher. It turned out that this mute wax figure on springs knew, if not how to speak, then at least, after a fashion, how to act. When one pockmarked, colossal retired captain, supported by a whole crew of various scum crowding at his back, began to pester him about "where to get to the buffet"—he winked to a policeman. The directive was promptly fulfilled: in spite of his swearing, the drunken captain was dragged out of the hall. Meanwhile, the "real" public also began finally to appear and in three long lines threaded its way down the three aisles between the chairs. The disorderly element began to quiet down, but the public, even the "cleanest" part of it, had a displeased and amazed look; some of the ladies were quite simply frightened.

Finally all were seated; the music also died down. People began blowing their noses, looking around. They were altogether too solemnly expectant—which is always a bad sign in itself. But the "Lembkas" were still not there. Silks, velvets, diamonds shone and sparkled on all sides; fragrance permeated the air. The men were wearing all their decorations, and the old men were even wearing their uniforms. Finally, the marshal's wife also appeared, together with Liza. Never before had Liza been so dazzlingly lovely as that morning, or so magnificently attired. Her hair was done up in curls, her eyes flashed, a smile shone on her face. She produced a visible effect; she was looked over, whispered about. People said she was seeking Stavrogin with her eyes, but neither Stavrogin nor Varvara Petrovna was there. I did not then understand the expression of her face: why was there so much happiness, joy, energy, strength in this face? I kept recalling yesterday's event, and was nonplussed. The "Lembkas," however, were still not there. This was indeed a mistake. I learned afterwards that Yulia Mikhailovna had waited till the last minute for Pyotr Stepanovich, without whom she could not take a step lately, though she never admitted it to herself. I will note in parenthesis that at the last committee meeting, the previous day, Pyotr Stepanovich had refused the usher's bow, which had upset her very much, even to tears. To her surprise, and afterwards to her great embarrassment (which I announce beforehand), he disappeared for the whole morning and did not come to the literary reading at all, so that no one met him until that same evening. Finally, the public began to show obvious impatience. No one appeared on the platform, either. In the back rows people began clapping as in a theater. Old men and ladies were frowning: the "Lembkas" were obviously giving themselves too many airs. Even among the best part of the public an absurd whispering began, that perhaps the fête would indeed not take place, that perhaps Lembke himself was indeed quite unwell, and so on and so forth. But, thank God, the Lembkes finally appeared, he leading her by the arm—I confess, I myself was terribly worried about their appearance. But the fables thus were falling, and truth was claiming its own. The public seemed relieved. Lembke himself, apparently, was in perfect health, as I recall everyone else also concluded, for one can imagine how many eyes were turned on him. I will note as characteristic that generally very few people in our higher society supposed that Lembke was somehow not quite well; and his deeds were found perfectly normal, so much so that even the previous day's episode in the square was received with approval. "Should've done it that way from the start,” the dignitaries said. "But no, they come as philanthropists and end up with the same thing, without noticing that it's necessary for philanthropy itself—so at least they reasoned in the club. They only blamed him for getting into a temper over it. "One has to keep cool, but after all the man is new at it," the connoisseurs said. With equal greediness all eyes turned to Yulia Mikhailovna as well. Of course, no one has the right to demand of me as a narrator too detailed an account of one point: here is mystery, here is woman; but one thing I do know: the previous evening she had gone into Andrei Antonovich's study and was with him till well past midnight. Andrei Antonovich was forgiven and consoled. The spouses agreed in all things, everything was forgotten, and when at the end of their talk von Lembke did go on his knees all the same, remembering with horror the main concluding episode of the previous night, the lovely little hand, and after it the lips, of his spouse blocked the fiery outpouring of penitent speeches of a man chivalrously delicate, yet weakened by tenderness. Everyone saw happiness on her face. She walked with a candid air and in a splendid dress. It seemed she was at the summit of her desires, the fête—the goal and crown of her politics—was realized. As they proceeded to their places just in front of the platform, both Lembkes were bowing and responding to others' bows. They were surrounded at once. The marshal's wife rose to meet them... But here a nasty misunderstanding occurred: the orchestra, out of the blue, burst into a flourish—not some sort of march, but simply a dinnertime flourish, as at table in our club, when they drink someone's health during an official banquet. I know now that this was owing to the good services of Lyamshin, in his capacity as usher, supposedly to honor the entrance of the "Lembkas." Of course, he could always make the excuse that he had done it out of stupidity or excessive zeal. . . Alas, I did not yet know that by then they were no longer worried about making excuses, and that that day was to put an end to everything. But the flourish was not the end of it: along with the vexatious bewilderment and smiling of the public, suddenly, from the end of the hall and from the gallery there came a hurrah,also as if in honor of the Lembkes. The voices were few, but I confess they lasted for some time. Yulia Mikhailovna turned red; her eyes flashed. Lembke had stopped by his place and, turning in the direction of those who were shouting, was grandly and sternly surveying the hall... He was quickly seated. I noticed with fear that same dangerous smile on his face with which he had stood yesterday morning in his wife's drawing room and looked at Stepan Trofimovich before going up to him. It seemed to me that now, too, there was some ominous expression on his face, and, worst of all, a slightly comical one, the expression of a being who is offering himself—oh, very well– as a sacrifice, only to play up to the higher aims of his wife... Yulia Mikhailovna hastily beckoned me to her and whispered that I should run to Karmazinov and beg him to begin. No sooner had I turned around than another abomination occurred, only much nastier than the first one. On the platform, on the empty platform, to which till that moment all eyes and all expectations had been turned, and where all that could be seen was a small table, a chair before it, and on the table a glass of water on a little silver tray—on this empty platform suddenly flashed the colossal figure of Captain Lebyadkin in a tailcoat and white tie. I was so struck that I did not believe my eyes. The captain, it seems, became abashed and halted at the rear of the platform. Suddenly, from amid the public, a shout was heard: "Lebyadkin! you?" The captain's stupid red mug (he was totally drunk) spread at this cry into a broad, dumb smile. He raised his hand, rubbed his forehead with it, shook his shaggy head, and, as if venturing all, stepped two steps forward and– suddenly snorted with laughter, not loud but long, happy, rippling, which sent his whole fleshy mass heaving and made his little eyes shrink. At the sight of this, nearly half the public laughed, twenty people applauded. The serious public gloomily exchanged glances; all this, however, lasted no more than half a minute. Suddenly Liputin with his usher's bow and two servants ran out on the platform; they carefully took the captain under both arms, while Liputin did a bit of whispering in his ear. The captain frowned, muttered "Ah, well, in that case," waved his hand, turned his enormous back to the public, and disappeared with his escort. But a moment later Liputin again jumped out on the platform. On his lips was the sweetest of his perennial smiles, which usually resembled vinegar and sugar, and in his hands was a sheet of writing paper. With small but rapid steps he came to the edge of the platform.

"Ladies and gentlemen," he addressed the public, "by oversight a comical misunderstanding took place, which has been removed; but I, not without hope, have taken upon myself a charge and a profound, most respectful request from one of our local town bards... Moved by a humane and lofty goal ... in spite of his looks... the very same goal which has united us all... to dry the tears of the poor educated girls of our province... this gentleman—that is, I mean to say, this local poet... while wishing to preserve his incognito... very much wished to see his poem read before the start of the ball... that is, I meant to say—the reading. Although this poem is not on the program and doesn't figure... because it was delivered only half an hour ago... yet it seemed to us"(us who? I am citing this abrupt and muddled speech verbatim) "that with its remarkable naivety of feeling, combined with as remarkable a gaiety, the poem could be read—that is, not as something serious, but as something suited to the festivities... To the idea, in short... Moreover, these few lines... and so I wanted to ask permission of the benevolent public."

"Read it!" barked a voice from the end of the hall.

"Shall I read it, then?"

"Read it, read it!" came many voices.

"I'll read it, with the public's permission," Liputin twisted himself up again, with the same sugary smile. It seemed as if he still could not make up his mind, and I even had the impression that he was worried. These people sometimes stumble, for all their boldness. However, a seminarian would not have stumbled, and Liputin did, after all, belong to the old society.

"I warn you—I mean, I have the honor of warning you—that all the same this is not really the kind of ode that once used to be written for festive occasions, this is almost, so to speak, a joke, but combining indisputable feeling and playful gaiety, and with, so to speak, the realmost truth."

"Read it, read it!"

He unfolded the piece of paper. Of course, no one had time to stop him. Besides, he was there with an usher's bow. In a ringing voice he declaimed:

"To the fatherland's governess of local parts from a poet at the fête.

"I give you greetings grand and grander, Governess! Be triumphant now, Retrograde or true George-Sander, Be exultant anyhow!"

"But that's Lebyadkin's! It is, it's Lebyadkin's!" several voices echoed. There was laughter and even applause, though not widespread.

"You teach our snot-nosed children French From an alphabetic book, The beadle even, in a pinch, For marriage you won't overlook!"

"Hoorah! hoorah!"

"But now, when great reforms are flowering, Even a beadle's hard to hook: Unless, young miss, you've got a 'dowering,' It's back to the alphabetic book."

"Precisely, precisely, that's realism, not a step without a 'dowering'!"

"Today, however, with our hosting We have raised much capital, And while dancing here we're posting A dowry to you from this hall.

Retrograde or true George-Sander, Be exultant anyhow! Governess by dower grander, Spit on the rest and triumph now!"

I confess, I did not believe my ears. Here was such obvious impudence that it was impossible to excuse Liputin even by stupidity. And, anyway, Liputin was far from stupid. The intention was clear, to me at least: they were as if hastening the disorder. Some lines of this idiotic poem, the very last one, for example, were of a sort that no stupidity would allow. Liputin himself seemed to feel that he had taken on too much: having accomplished his great deed, he was so taken aback by his own boldness that he did not even leave the platform, but went on standing there as if wishing to add something. He must have supposed it would come out somehow differently; but even the bunch of hooligans who had applauded during the escapade suddenly fell silent, as if they, too, were taken aback. Stupidest of all was that many of them took the whole escapade in a pathetic sense—that is, not as lampoonery, but indeed as the real truth concerning governesses, as verse with a tendency. But these people, too, were finally struck by the excessive license of the poem. As for the rest of the public, the entire hall was not only scandalized but visibly offended. I am not mistaken in conveying the impression. Yulia Mikhailovna said afterwards that she would have fainted in another moment. One of the most venerable little old men helped his little old lady to her feet, and they both left the hall, followed by the alarmed eyes of the public. Who knows, the example might have carried others along as well, if at that moment Karmazinov himself had not appeared on the platform, in a tailcoat and white tie, and with a notebook in his hand. Yulia Mikhailovna turned rapturous eyes to him, as to a deliverer... But by then I had already gone backstage; I was after Liputin.