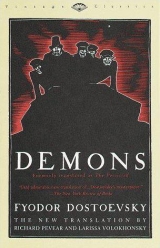

Текст книги "Demons"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 40 (всего у книги 56 страниц)

"It's all arson! It's nihilism! If anything's ablaze, it's nihilism!" I heard all but with horror, and though there was no longer anything to be astonished at, still manifest reality always has something shocking about it.

"Your Excellency," a policeman turned up beside him, "if you'd be so good as to try domestic repose, sir... the way it is, it's even dangerous for Your Excellency to be standing here."

This policeman, as I learned later, was purposely left with Andrei Antonovich by the police chief, to watch over him and try as hard as he could to take him home, and in case of danger even to act with force—a charge obviously beyond the powers of its executor.

"The tears of the burnt-out people will be wiped away, but the town will be burned. It's all four blackguards, four and a half. Arrest the blackguard! He's in it alone, and has slandered the four and a half. He worms himself into the honor of families. Governesses have been used to set houses on fire. This is mean, mean! Aie, what is he doing?" he cried, suddenly noticing a fireman on the roof of the blazing cottage, the roof already burned through under him and fire flaring up all around. "Pull him down, pull him down, he'll fall through, he'll catch fire, put him out... What is he doing up there?"

"Putting it out, Your Excellency."

"Unbelievable. The fire is in people's minds, not on the rooftops. Pull him down and drop it all! Better drop it, drop it! Leave it to itself somehow! Aie, who is that still crying? An old woman! An old woman is shouting, why did you forget the old woman?"

Indeed, a forgotten old woman was shouting on the bottom floor of the blazing cottage, the eighty-year-old relative of the merchant who owned the burning house. But she had not been forgotten; she had gone back into the burning house herself while it was possible, with the insane purpose of dragging her feather bed out of the still untouched corner room. Choking from the smoke and shouting from the heat, because that room, too, had caught fire, she was still trying with all her might to push her feather bed through a broken window with her decrepit hands. Lembke rushed to help her. Everyone saw him run up to the window, seize a corner of the feather bed and begin to pull it through the window with all his might. As bad luck would have it, at that very moment a broken board fell from the roof and struck the unfortunate man. It did not kill him, it merely grazed his neck with one end as it fell, but the career of Andrei Antonovich was over, at least among us; the blow knocked him off his feet, and he collapsed unconscious.

At last came a sullen, gloomy dawn. The fire dwindled; after the wind it suddenly became still, and then came a slow, drizzling rain, as if through a sieve. I was by then in another part of Zarechye, far from the spot where Lembke had fallen, and there in the crowd I heard very strange talk. A strange fact had been discovered: at the edge of the quarter, on a vacant lot beyond the kitchen gardens, not less than fifty steps away from the other buildings, there stood a small, recently built wooden house, and this solitary house had burst into flames almost before any of the others, at the very beginning of the fire. Even if it had burned down, it could not have transmitted the fire to any town buildings because of the distance, and, vice versa, if the whole of Zarechye had burned down, this one house would have remained untouched, whatever wind was blowing. It appeared to have caught fire separately and independently, so there was something behind it. But the main thing was that it had not had time to burn down, and towards daybreak astonishing things were discovered inside it. The owner of this new house, a tradesman who lived in the nearby quarter, as soon as he saw his new house on fire, rushed to it and managed to save it, with the help of some neighbors, by scattering the burning logs that had been piled against the side wall. But there were tenants living in the house—a captain well known in town, his sister, and with them an elderly servingwoman, and these tenants, the captain, his sister, and the servingwoman, had all three been stabbed to death that night and apparently robbed. (It was here that the police chief had gone when he had left the fire while Lembke was trying to rescue the feather bed.) By morning the news had spread and a huge mass of all sorts of people, even some who had been burned out in Zarechye, poured down to the vacant lot, to the new house. It was so crowded that it was even difficult to get through. I was told at once that the captain had been found with his throat cut, on the bench, dressed, and that he had probably been dead drunk when he was killed, so that he had not even felt it, and that he had bled "like a bull"; that his sister Marya Timofeevna had been "stuck all over" with a knife, and was lying on the floor of the doorway, so that she had probably been awake and had struggled and fought with the murderer. The housekeeper, who probably also woke up, had her head completely smashed in. According to the owner's story, the captain had come to see him the day before, in the morning, had boasted and displayed a lot of money, as much as two hundred roubles. The captain's old, worn green wallet was found empty on the floor; but Marya Timofeevna's trunk had not been touched, and the silver casing of her icon had not been touched either; of the captain's clothes, everything turned out to be intact as well; one could see that the thief had been in a hurry, and that he was a man who was familiar with the captain's affairs, had come to take money only, and knew where to find it. If the owner had not come running right away, the logs would have flared up and quite certainly burned the house down, "and it would have been difficult to learn the truth from charred corpses."

So ran the account of the affair. Further information was added: that the place had been rented for the captain and his sister personally by Mr. Stavrogin, Nikolai Vsevolodovich, General Stavrogin's widow's boy, that he had come personally to rent it, and had been very insistent, because the owner did not want to let it and was intending to make the house a tavern, but Nikolai Vsevolodovich had spared no expense and handed him money for a year in advance.

"There's something behind this fire," voices came from the crowd.

But the majority were silent. Their faces were gloomy, but I did not notice any great, obvious irritation. All around, however, stories went on about Nikolai Vsevolodovich, that the murdered woman was his wife, that yesterday, "in a dishonest manner," he had lured to himself a young lady from the foremost house in town, the daughter of General Drozdov's widow, that a complaint would be lodged against him in Petersburg, and that if his wife had been killed, it must have been so that he could marry the Drozdov girl. Skvoreshniki was no more than a mile and a half away, and I remember thinking: shouldn't I send word to them there? However, I did not notice anyone especially inciting the crowd, and I do not want to speak evil, though I did see flash by me two or three "buffet" mugs, who turned up at the fire by morning and whom I recognized at once. I particularly remember one tall, lean fellow, a tradesman, haggard, curly-haired, as if smeared with soot—a locksmith, as I learned later. He was not drunk, but, in contrast to the gloomily standing crowd, seemed beside himself. He kept addressing the people, though I do not remember his words. Whatever was coherent was no longer than: "What's this, brothers? Can it really be like this?"—all the while waving his arms.

3: A Finished Romance

I

From the big reception room at Skvoreshniki (the same one in which the last meeting between Varvara Petrovna and Stepan Trofimovich had taken place), the fire was in full view. At dawn, towards six o'clock, Liza was standing at the last window on the right, looking intently at the dying glow. She was alone in the room. The dress she was wearing was the festive one from the day before, in which she had appeared at the reading—light green, magnificent, all lace, but rumpled now, hastily and carelessly put on. Suddenly noticing that the front of the dress was not tightly fastened, she blushed, hastily put it right, snatched from the armchair a red shawl left there the day before when she came in, and threw it around her neck. Her fluffy hair fell in disorderly curls onto her right shoulder from under the shawl. Her face was tired, preoccupied, but her eyes were burning from under her frowning brows. She went up to the window again and leaned her hot forehead against the cold glass. The door opened and Nikolai Vsevolodovich came in.

"I've sent a messenger on horseback," he said, "in ten minutes we'll learn everything, but meanwhile the servants are saying that part of Zarechye has burned down, nearer the embankment, to the right from the bridge. It started burning before twelve; it's going out now."

He did not go to the window, but stopped three steps behind her, yet she did not turn to him.

"By the calendar it ought to have been light an hour ago, and it's still like night," she said with vexation.

"Every calendar doth lie," [185]he remarked with an obliging grin, but, ashamed, hastened to add: "It's boring to live by the calendar, Liza."

And he fell silent finally, vexed at the new platitude he had uttered; Liza smiled crookedly.

"You're in such a sad mood that you can't even find words with me. But don't worry, you put it appropriately: I always live by the calendar, my every step is reckoned by the calendar. Are you surprised?"

She quickly turned away from the window and sat down in an armchair.

"You sit down, too, please. We won't be together long, and I want to say whatever I like... Why shouldn't you, too, say whatever you like?"

Nikolai Vsevolodovich sat down beside her and gently, almost timorously, took her hand.

"What does this language mean, Liza? Where does it come from so suddenly? What is the meaning of 'we won't be together long'? This is the second mysterious phrase since you woke up half an hour ago."

"You've started counting my mysterious phrases?" she laughed. "And do you remember how yesterday, as I came in, I introduced myself as a dead person? You found it necessary to forget that. To forget or not to notice."

"I don't remember, Liza. Why a dead person? One must live..."

"And you stop short. You've quite lost your eloquence. I've lived my hour in the world, and enough. Do you remember Khristofor Ivanovich?"

"No, I don't," he frowned.

"Khristofor Ivanovich, in Lausanne? You got terribly sick of him. He'd open the door and always say, 'I've just come for a minute,' and he'd sit for the whole day. I don't want to be like Khristofor Ivanovich and sit for the whole day."

A pained impression came to his face.

"Liza, this broken language grieves me. This grimacing must cost you dearly. What is it for? Why?"

His eyes lit up.

"Liza," he exclaimed, "I swear I love you more now than yesterday when you came to me!"

"What a strange confession! Why this yesterday and today, these two measures?"

"You won't abandon me," he went on, almost with despair, "we'll leave together, this very day, right? Right?"

"Aie, don't squeeze my hand so painfully! Where are we going to go together this very day? To 'resurrect' somewhere again? No, enough trying... and it's too slow for me; and I'm not able; it's too high for me. If we're to go, it should be to Moscow, to pay calls there and receive people—that's my ideal, you know; even in Switzerland I didn't conceal from you how I am. Since it's not possible for us to go to Moscow and pay calls, because you're married, there's no point in talking about it."

"Liza! What was it yesterday, then?"

"It was what it was."

"That's impossible! That's cruel!"

"So what if it's cruel; just endure it, if it's cruel."

"You're taking revenge on me for yesterday's fantasy..." he muttered, grinning spitefully. Liza flushed.

"What a base thought!"

"Then why did you give me ... 'so much happiness'? Do I have the right to know?"

"No, try doing without rights somehow; don't crown the baseness of your suggestion with foolishness. You're not doing well today. Incidentally, are you not perchance afraid of the world's opinion, and that you'll be condemned for this 'so much happiness'? Oh, if you are, for God's sake don't worry. You didn't cause anything, and you're not answerable to anyone. When I was opening your door yesterday, you didn't even know who was coming in. Here it was precisely my fantasy alone, as you just put it, and nothing more. You can look everyone boldly and triumphantly in the eye."

"Your words, this laughter, for an hour already they've been sending a chill of horror over me. This 'happiness' you're now talking about so frenziedly has cost me... everything. How can I lose you now? I swear I loved you less yesterday. Why then do you take everything from me today? Do you know how much it cost me, this new hope? I paid for it with life."

"Your own or someone else's?"

He got up quickly.

"What does that mean?" he said, looking at her motionlessly.

"Paid with your own life or with mine, that is what I wanted to ask. Or have you now lost all understanding entirely?" Liza flushed. "Why did you jump up so suddenly? Why are you looking at me that way? You scare me. Why are you afraid all the time? I noticed a while ago that you're afraid, precisely now, precisely at this moment... Lord, you're turning so pale!"

"If you know anything, Liza, I swear that Ido not. . . and I wasn't talking about thatjust now when I spoke of paying with life..."

"I don't understand you at all," she said, faltering timorously.

At last a slow, pensive grin appeared on his lips. He slowly sat down, put his elbows on his knees, and covered his face with his hands.

"A bad dream and delirium ... We were talking about two different things."

"I don't know at all what you were talking about... Did you really not know yesterday that I would leave you today, did you or did you not? Don't lie, did you know or did you not?"

"I did..." he uttered softly.

"So what do you want: you knew it, and you reserved 'the moment' for yourself. How can there be any score?"

"Tell me the whole truth," he cried out with deep suffering, "when you opened my door yesterday, did you know yourself that you were opening it for one hour only?"

She looked at him with hatred:

"Truly, the most serious man can ask the most amazing questions. And why do you worry so? Can it be out of pride that a woman left you first, and not you her? You know, Nikolai Vsevolodovich, since I've been here I've become convinced, among other things, that you are being terribly magnanimous towards me, and that is precisely what I cannot endure in you."

He got up from his place and walked several steps about the room.

"Very well, suppose it has to end this way... But how could it all have happened?"

"Who cares! And the main thing is that you yourself can tell it off on your own fingers and understand it better than anyone in the world and were counting on it. I am a young lady, my heart was brought up in the opera, it started there, that's the whole answer."

"No."

"There's nothing here that can gall your pride, and it's all perfectly true. It began with a beautiful moment which I could not endure. Two days ago when I 'offended' you before all the world, and you gave me such a chivalrous reply, I came home and guessed at once that you were running away from me because you were married, and not at all out of contempt for me—which is what I, being a young lady of fashion, was most afraid of. I understood that it was me, a reckless girl, that you were protecting by running away. You see how I value your magnanimity. Then Pyotr Stepanovich jumped up to me and explained it all at once. He revealed to me that you were being shaken by a great idea, before which he and I were utterly nothing, but that I still stood in your way. He included himself in it; he absolutely wanted it to be the three of us together, and said the most fantastic things about a bark and maple oars from some Russian song. I praised him, said he was a poet, and he took it for pure gold. And since I'd known for a long time, even without that, that I'd never last more than a moment, I just up and decided. So that's all, and enough, and, please, no more explanations. Otherwise we might quarrel. Don't be afraid of anyone, I take it all upon myself. I'm bad, I'm capricious, I got tempted by an operatic bark, I'm a young lady ... But, you know, I still thought you loved me terribly. Don't despise a foolish girl or laugh at this little tear that just fell. I like terribly much to cry and 'pity myself.' Well, enough, enough. I'm not capable of anything, you're not capable of anything; two flicks, one on each side, and let that be a comfort to us. At least our pride doesn't suffer."

"Dream and delirium!" Nikolai Vsevolodovich cried out, wringing his hands and pacing the room. "Liza, poor Liza, what have you done to yourself?"

"Burned myself in a candle, that's all. Are you crying, too? Be more decent, more unfeeling..."

"Why, why did you come to me?"

"But don't you understand, finally, what a comical position you put yourself in before worldly opinion by asking such questions?"

"Why did you ruin yourself in such an ugly and stupid way, and what is to be done now?"

"And this is Stavrogin, the 'bloodsucker Stavrogin,' as one lady here who is in love with you calls you! Listen, I already told you: I've traded my life for a single hour, and I'm at peace. Trade yours the same way... though you've got no reason to; you'll still have so many different 'hours' and 'moments.’”

"As many as you have; I give you my great word, not an hour more than you have!"

He kept pacing and did not see her quick, piercing look which suddenly seemed to light up with hope. But the ray of light went out at the same moment.

"If you knew the price of my present impossiblesincerity, Liza, if only I could reveal it to you..."

"Reveal? You want to reveal something to me? God save me from your revelations!" she interrupted, almost fearfully.

He stopped and waited uneasily.

"I must confess to you, ever since Switzerland the thought has settled in me that there is something horrible, dirty, and bloody on your soul, and ... at the same time something that makes you look terribly ridiculous. Beware of revealing it to me, if it's true: I'll ridicule you. I'll laugh at you all your life... Aie, you're turning pale again? I won't, I won't, I'll leave at once," she jumped up from the chair with a squeamish and scornful gesture.

"Torment me, punish me, vent your spite on me," he cried out in despair. "You have every right! I knew I didn't love you, and I ruined you. Yes, 'I reserved the moment for myself; I had a hope ... for a long time ... a last hope ... I couldn't resist the light that shone in my heart when you came to me yesterday, yourself, alone, first. I suddenly believed... maybe I believe even now."

"For such noble sincerity I shall repay you in kind. I do not want to be your tenderhearted nurse. Suppose I do indeed become a sick-nurse, unless I incidentally manage to die this very day; still, if I do, it won't be to you, though of course you're worth anyone legless or armless. It has always seemed to me that you would bring me to some place where there lives a huge, evil spider, as big as a man, and we would spend our whole life there looking at him and being afraid.

That's how our mutual love would pass. Address yourself to Dashenka; she'll go with you wherever you like."

"And even now you can't help recalling her?"

"Poor puppy! Give her my regards. Does she know you intend her for your old age in Switzerland? What consideration! What foresight! Aie, who's there?"

At the far end of the room the door opened a tiny bit; someone's head stuck itself in and quickly hid.

"Is that you, Alexei Yegorych?" Stavrogin asked.

"No, it's only me," Pyotr Stepanovich again stuck in the upper half of himself. "Hello, Lizaveta Nikolaevna; or, anyhow, good morning. I just knew I'd find you both in this room. Absolutely for just one moment, Nikolai Vsevolodovich—I hurried here at all costs for a couple of words... most necessary words ... a couple, no more!"

Stavrogin started to go, but after three steps he returned to Liza.

"If you hear anything now, Liza, know this: I am guilty."

She gave a start and looked at him timorously; but he hurriedly went out.

II

The room Pyotr Stepanovich had peeked out from was a big oval anteroom. Before he came, Alexei Yegorych had been sitting there, but he sent him away. Nikolai Vsevolodovich closed the door to the reception room behind himself and stopped in expectation. Pyotr Stepanovich looked him over quickly and inquisitively.

"Well?"

"I mean, if you already know," Pyotr Stepanovich hurried on, wishing, it seemed, to jump into the man's soul with his eyes, "then, of course, none of us is guilty of anything, and you first of all, because it's such a conjunction ... a coincidence of events ... in short, legally it cannot involve you, and I flew here to forewarn you."

"They're burned? Killed?"

"Killed but not burned, and that's the bad thing, but I give you my word of honor that I'm not guilty there either, however much you suspect me—because maybe you do suspect me, eh? Want the whole truth? You see, the thought did indeed occur to me—you prompted me to it yourself, not seriously, teasing me (because you wouldn't really prompt me seriously), but I didn't dare, and I wouldn't have dared for anything, not even for a hundred roubles—and there isn't any profit in it, I mean for me, for me..." (He hurried terribly and spoke like a rattle.) "But look what a coincidence of circumstances: I gave that drunken fool Lebyadkin two hundred and thirty roubles of my own (of my own, you hear, of my own, not a rouble of it was yours, and, moreover, you know that yourself), two days ago, already that evening—you hear, two days ago, not yesterday after the 'reading,' note that: it's a rather important coincidence, because I didn't know anything for certain then about Lizaveta Nikolaevna's going to you or not; and I gave my own money solely because two days ago you distinguished yourself by deciding to announce your secret to everyone. Well, I'm not getting into... it's your business... this chivalry... but, I confess, it surprised me, like a clout on the head. But since I am exceeding weary of all these tragedies—and note that I'm speaking seriously, though I'm using antiquated expressions—since it's all finally harmful to my plans, I swore to myself I'd pack the Lebyadkins off to Petersburg at all costs and without your knowledge, the more so since he was anxious to go there himself. One mistake: I gave him the money on your behalf; was it a mistake, or not? Maybe not, eh? Now listen, listen to how it all turned out..." In the fever of talking he moved up very close to Stavrogin and went to grab him by the lapel of his jacket (maybe on purpose, by God). Stavrogin, with a strong movement, hit him on the arm.

"What's this now ... come on ... you'll break my arm ... the main thing here is how it turned out," he rattled on, not even the least surprised at being hit. "I hand him the money in the evening, so that he and his dear sister can set out the next day at dawn; I charge the scoundrel Liputin with that little business, putting them on the train and seeing them off himself. But the blackguard Liputin felt the need to pull a prank on the public—maybe you heard? At the 'reading'? So listen, listen: the two of them drink, compose verses, half belonging to Liputin; he dresses him up in a tailcoat, assures me he sent him off in the morning, all the while keeping him somewhere in a back closet, in order to push him out onto the platform. But he quickly and unexpectedly gets drunk. Then the notorious scandal, then he's brought home more dead than alive, and Liputin takes the two hundred roubles from him on the sly, leaving him some change. But, unfortunately, it turns out that he had already taken the two hundred out of his pocket in the morning, boasting and showing it where he shouldn't have. And since Fedka was just waiting for that, and had heard something at Kirillov's (remember your hint?), he decided to make use of it. That's the whole truth. I'm glad at least that Fedka didn't find the money– and he was counting on getting a thousand, the scoundrel! He was in a hurry and, it seems, was frightened by the fire himself... Would you believe it, that fire was a real whack on the head for me. No, it's the devil knows what! It's such high-handedness... Look, I won't conceal anything, since I expect so much from you: so, yes, I've had this little idea of a fire ripening in me for a long time, since it's so national and popular; but I was keeping it for a critical hour, for that precious moment when we all rise up and... And they suddenly decided it high-handedly and without any orders, now, precisely when they should have laid low and held their breath! No, it's such highhandedness! ... in short, I still don't know anything, they're talking here about two Shpigulin men... but if ourswere in it as well, if any one of them warmed his hands at it—woe to him! You see what it means to slacken even a little! No, this democratic scum with its fivesomes is a poor support; what we need is one splendid, monumental, despotic will, supported by something external and not accidental... Then the fivesomes will also put their tails of obedience between their legs, and their obsequiousness will occasionally come in handy. Anyhow, though it's being shouted in all trumpets that Stavrogin needed to burn his wife, and that's why the town got burned down, still ..."

"They're already shouting in all trumpets?"

"I mean, not at all so far, and, I confess, I've heard nothing whatsoever, but what can you do with people, especially when they've been burned out: Vox populi vox dei. [186] How long does it take to blow the stupidest rumor to the four winds?... But as a matter of fact you have nothing whatsoever to fear. Legally, you're completely in the right, and morally, too—because you didn't want it, eh? Did you? There's no evidence, just a coincidence ... Unless Fedka happens to recall your imprudent words that time at Kirillov's (and why did you say that then?), but that proves nothing at all, and we will cancel Fedka. I'm canceling him today..."

"And the bodies didn't burn at all?"

"Not a bit; that rascal couldn't arrange anything properly. But I'm glad at least that you're so calm... because though you're not guilty in any way, not even in thought, still, all the same. And, besides, you must agree that all this gives an excellent turn to your affairs: suddenly you're a free widower and at this very moment can marry a wonderful girl with enormous money, who, on top of that, is already in your hands. That's what a simple, crude coincidence of circumstances can do—eh?"

"Are you threatening me, foolish head?"

"Eh, enough, enough, right away I'm a foolish head! And what's this tone? Instead of being glad, you ... I came flying especially to forewarn you sooner ... And how am I going to threaten you? As if I need you under threat! I need your good will, and not out of fear. You are the light, the sun... It's I who am afraid of you with all my might, not you of me! I'm not Mavriky Nikolaevich... And, imagine, I'm flying here in a racing droshky, and there's Mavriky Nikolaevich by the garden fence, at the back corner of the garden ... in his greatcoat, soaked through, must have been sitting there all night! Wonders! How people can lose their minds!"

"Mavriky Nikolaevich? Is it true?"

"True, true. Sitting by the garden fence. From here—about three hundred steps from here, I suppose. I hurried to get past him, but he saw me. You didn't know? In that case I'm very glad I didn't forget to tell you. His kind is most dangerous if he happens to have a revolver, and, finally, the night, the slush, the natural irritation—because look what situation he's in now, ha, ha! Why do you think he's sitting there?"

"Waiting for Lizaveta Nikolaevna, of course."

"Ah-ha! But why should she go out to him? And ... in such rain... what a fool!"

"She will go out to him presently."

"Ehh! That's news! So then ... But listen, her affairs are completely changed now: what need does she have for Mavriky now? When you're a free widower and can marry her tomorrow? She doesn't know yet—leave it to me, I'll take care of it right away. Where is she, I must make her happy with the news."

"Happy?"

"What else! Let's go."

"And you think she won't guess about those corpses?" Stavrogin narrowed his eyes somehow peculiarly.

"Of course she won't," Pyotr Stepanovich picked up like a decided little fool, "because legally... Eh, you! But even if she does guess! With women it all gets so excellently shaded in—you still don't know women! Besides, it's entirely to her profit to marry you now, because she's made a scandal of herself, after all, and, besides, I told her a pile of stuff about the 'bark': I precisely thought one could affect her with the 'bark,' so that's the caliber of the girl. Don't worry, she'll step over those little corpses all right, and la-di-da!—the more so as you're perfectly, perfectly innocent, isn't that so? She'll just stash those little corpses away so as to needle you later on, say in the second year of your marriage. Every woman on her way to the altar keeps something like that stored up from her husband's old days, but then ... what will it be like in a year? Ha, ha, ha!"

"If you came in a racing droshky, take her now to Mavriky Nikolaevich. She said just now that she couldn't stand me and was going to leave me, and she certainly won't accept my carriage."

"Ah-ha! She's really leaving? What might have brought that about?" Pyotr Stepanovich gave a silly look.

"She guessed somehow during the night that I don't love her at all... which, of course, she's always known."