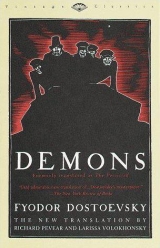

Текст книги "Demons"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 56 страниц)

7: With Our People

I

Virginsky lived in his own house, that is, in his wife's house, on Muravyiny Street. It was a one-story wooden house, and there were no other lodgers in it. Under the pretense of the host's birthday about fifteen guests had gathered; but the party in no way resembled an ordinary provincial name-day party. From the very beginning of their cohabitation, the Virginsky spouses mutually resolved once and for all that to invite guests for one's name day was perfectly stupid, and besides "there's nothing at all to be glad about." In a few years they had somehow managed to distance themselves completely from society. He, though a man of ability, and by no means a "poor sort," for some reason seemed to everyone an odd man who loved solitude and, moreover, spoke "arrogantly." While Madame Virginsky herself, who practiced the profession of midwife, by that alone stood lowest of all on the social ladder, even lower than the priest's wife, despite her husband's rank as an officer. As for the humility befitting her station, this could not be observed in her at all. And after a most stupid and unforgivably open liaison, on principle, with a certain crook, one Captain Lebyadkin, even the most lenient of our ladies turned away from her with remarkable disdain. Yet Madame Virginsky took it all as if it were just what she wanted. Remarkably, the very same severe ladies, should they happen to be in an interesting condition, turned if possible to Arina Prokhorovna (Virginsky, that is), bypassing the other three accoucheusesof our town. She was summoned even by country landowners' wives—so great was everyone's belief in her knowledge, luck, and adroitness in critical cases. The end was that she began to practice solely in the wealthiest houses; and she loved money to the point of greed. Having fully sensed her power, she finally stopped restraining her character altogether. Perhaps it was even on purpose that, while working in the most distinguished houses, she would frighten a nervous woman in childbed with some unheard-of nihilistic forgetting of decency, or, finally, with her mockery of "all that's holy," precisely at moments when "the holy" might have been most useful. Our army doctor, Rozanov, an accoucheurhimself, bore positive witness that once, when a woman in labor was howling in pain and calling on the almighty name of God, it was precisely one of these freethinking outbursts from Arina Prokhorovna, sudden "like a rifle shot," that, by affecting the patient with fright, contributed to a most speedy delivery. But, though a nihilist, in case of necessity Arina Prokhorovna would not shrink at all, not only from social, but even from age-old, most prejudiced customs, if they could be of use to her. Not for anything would she miss, for example, the baptism of a baby she had delivered, and she would appear wearing a green silk dress with a train, and with her chignon combed into curls and ringlets, while at all other times she reached the point of reveling in her own slovenliness. And though she always maintained "a most insolent air" during the performance of the sacrament, to the embarrassment of the clergy, once the rite had been performed, it was she who unfailingly brought out the champagne (this was why she came, and got so dressed up), and woeto anyone who tried to take a glass from her without paying something "into the pot."

The guests who gathered at Virginsky's this time (almost all men) had some sort of accidental and urgent look. [146]There were no refreshments or cards. In the middle of the big drawing room, papered with supremely old blue wallpaper, two tables had been moved together and covered with a big tablecloth, not quite clean, incidentally, and on them two samovars were boiling. A huge tray with twenty-five glasses and a basket of ordinary French bread cut up into many slices, somewhat as in upper-class male and female children's boarding schools, occupied the end of the table. Tea was poured by a thirty-year-old maiden lady, the hostess's sister, browless and pale-haired, a silent and venomous being, but who shared in the new views, and of whom Virginsky, in his domestic existence, was terribly afraid. All together there were three ladies in the room: the hostess herself, her browless sister, and Virginsky's sister, the young Miss Virginsky, who had just got in from Petersburg. Arina Prokhorovna, an imposing lady of about twenty-seven, not bad-looking, somewhat unkempt, in a non-festive woolen dress of a greenish shade, was sitting and looking over her guests with a dauntless gaze, as if hastening to say with her eyes: "See how I'm not afraid of anything at all." The visiting Miss Virginsky, also not bad-looking, a student and a nihilist, well fed and well packed, like a little ball, with very red cheeks, and of short stature, had placed herself next to Arina Prokhorovna, still almost in her traveling clothes, with some bundle of papers in her hand, and was studying the guests with impatient, leaping eyes. Virginsky himself was somewhat unwell that evening, but he nevertheless came out and sat in an armchair at the tea table. The guests were all sitting down as well, and this decorous disposition on chairs around a table gave the suggestion of a meeting. Obviously they were all waiting for something, and, while waiting, engaged each other in loud but as if irrelevant conversation. When Stavrogin and Verkhovensky appeared, everything suddenly became hushed.

But I will allow myself some comments by way of clarification.

I believe that all these gentlemen had indeed gathered then in the pleasant hope of hearing something especially curious, and had been so informed before they gathered. They represented the flower of the most bright red liberalism in our ancient town and had been quite carefully selected by Virginsky for this "meeting." I will also note that some among them (though very few) had never visited him before. Of course, the majority of the guests had no clear notion of why they had been so informed. True, at that time they all took Pyotr Stepanovich for a visiting foreign emissary with plenary powers; this idea had somehow immediately taken root and, naturally, was flattering. And yet in this bunch of citizens gathered under the pretense of a name-day celebration, there were some to whom certain proposals had already been made. Pyotr Verkhovensky had managed to slap up a "fivesome" in our town, similar to the one he already had going in Moscow and also, as it now turns out, among the officers in our district. They say he had one in Kh– province as well. These five elect were now sitting at the general table and managed to feign quite skillfully the look of the most ordinary people, so that no one could recognize them. These were—since it is no longer a secret—first, Liputin, then Virginsky himself, long-eared Shigalyov (Mrs. Virginsky's brother), Lyamshin, and, finally, a certain Tolkachenko—a strange character, already a man of forty, and famous for his vast study of the people, predominantly crooks and robbers, for which purpose he frequented the pot-houses (not only to study the people, however), and who flaunted among us his bad clothing, tarred boots, squintingly sly look, and frilly folk expressions. Lyamshin had already brought him once or twice to Stepan Trofimovich's evenings, where, however, he had produced no special effect. He would appear in town every so often, mostly when he was out of a job, and he used to work for the railroad. All five of these activists made up this first crew in the warm belief that it was just one unit among hundreds and thousands of fivesomes of the same sort scattered all over Russia, and that they all depended on some central, enormous, but secret place, which in turn was organically linked with Europe's world revolution. But, unfortunately, I must confess that even then there had begun to be discord among them. The thing was that though they had been expecting Pyotr Verkhovensky since spring, as had been announced to them first by Tolkachenko and then by the newly arrived Shigalyov, though they were expecting extraordinary miracles from him, and though they had all come at once, without the slightest criticism and at his first call, to join the circle, yet they had no sooner made up the fivesome than they all at once became offended, as it were, and precisely, I suppose, because of the quickness of their consent. They had joined, of course, out of a magnanimous sense of shame, so that no one could say later that they had not dared to join; but, still, Pyotr Verkhovensky ought really to have appreciated their noble deed and at least have told them some foremost anecdote as a reward. But Verkhovensky did not have the slightest wish to satisfy their legitimate curiosity, and would not tell them anything unnecessary; generally, he treated them with remarkable sternness and even casualness. This was decidedly irritating, and member Shigalyov was already instigating the others "to demand an accounting," but, of course, not now, at Virginsky's, where so many outsiders had gathered.

Speaking of outsiders, I also have an idea that the above-named members of the first fivesome were inclined to suspect that among Virginsky's guests that evening there were members of other groups unknown to them, also started in town from the same secret organization, and by the selfsame Verkhovensky, so that in the end all of those gathered suspected each other, and assumed various postures in front of each other, which indeed lent the whole gathering a rather incoherent and even partly romantic appearance. However, there were also people there who were beyond any suspicion. Such, for example, was one active army major, Virginsky's close relative, a completely innocent man, who had not even been invited, but had come on his own to celebrate the name day, so that it was simply impossible not to receive him. But anyhow Virginsky was not worried, because the major "simply could not denounce them"; for, despite all his stupidity, he had been fond throughout his life of scurrying around all those places where extreme liberals are to be found; did not sympathize himself, but liked very much to listen. Moreover, he had even been compromised once: it so happened that in his youth whole warehouses of The Bell [147] and various tracts had passed through his hands, and though he had been afraid even to unfold them, he would still have regarded the refusal to disseminate them as perfect baseness—and there are some Russians of his sort even to this day. The remainder of the guests represented either the type of noble amour-propre crushed to the point of bile, or the type of the first and noblest impulse of fervent youth. These were two or three teachers, one of whom was lame, already about forty-five, an instructor in the high school, an extremely venomous and remarkably vain man, and two or three officers. Of the latter, one was a very young artillerist who had arrived just the other day from some military school, a silent boy who had not yet had time to make acquaintances, and who now suddenly turned up at Virginsky's with a pencil in his hand and, almost without taking part in the conversation, kept jotting things down in his notebook. Everyone saw this, but for some reason everyone tried to make it seem as if they had not noticed. There was also the loaf-about seminarian who together with Lyamshin had slipped the vile photographs into the book-hawker's bag, a big fellow with a free and easy but at the same time mistrustful manner, with a perpetually accusatory smile, and along with that a calm look of triumphant perfection contained within himself. There was, I have no idea why, also the son of our mayor, that same nasty boy, dissipated beyond his years, whom I have already mentioned while telling the story of the lieutenant's little wife. He was silent all evening. And finally, in conclusion, there was a high-school student, a very hot-headed and disheveled boy of about eighteen, who sat with the glum look of a young man whose dignity has been insulted, and suffered visibly on account of his eighteen years. This mite of a lad was already the head of an independent crew of conspirators formed in the upper grade of the high school, which fact was discovered afterwards to general amazement. I have not mentioned Shatov: he was sitting right there at the far corner of the table, his chair moved slightly out of line; he looked down, was gloomily silent, refused tea and bread, and would not let go of his peaked cap all the while, as if wishing thereby to declare that he was not a guest but had come on business, and could get up and leave whenever he liked. Not far from him sat Kirillov, also quite silent, though he did not look down but, on the contrary, examined each speaker point-blank with his fixed, lusterless stare, and listened to everything without the least emotion or surprise. Some of the guests who had never seen him before studied him stealthily and pensively. It is not known whether Madame Virginsky herself knew anything about the existence of the fivesome. I suppose she knew everything, and precisely from her husband. The girl student, of course, did not participate in any way, but she had her own concern: she intended to stay only for a day or two, and then go on farther and farther, to all the university towns, to "share the suffering lot of the poor students and arouse them to protest." She was bringing with her several hundred lithographed copies of an appeal– of her own composition, it would seem. Remarkably, the high-school boy hated her from first sight almost to the point of blood vengeance, though it was the first time he had seen her in his life, and she him. The major was her uncle, and met her that day for the first time in ten years. When Stavrogin and Verkhovensky entered, her cheeks were as red as cranberries: she had just had a spat with her uncle over their views of the woman question.

II

Verkhovensky sprawled himself with remarkable casualness on a chair at the upper corner of the table, greeting almost no one. His look was squeamish, and even arrogant. Stavrogin politely made his bows, but, despite the fact that everyone had been waiting only for them, everyone, as if on command, pretended that they had scarcely noticed them. The hostess sternly addressed Stavrogin as soon as he sat down.

"Stavrogin, you want tea?"

"Thanks," he replied.

"Tea for Stavrogin," she commanded the pouring woman, "and what about you?" (this was now to Verkhovensky).

"Of course I do, what a thing to ask a guest! And give me cream, too. You always serve such vileness instead of tea—and for a name-day party at that."

"What, you also recognize name days?" the girl student suddenly laughed. "We were just talking about that."

"It's old hat," the high-school boy grumbled from the other end of the table.

"What is old hat? To forget prejudices, innocent though they may be, isn't old hat but, on the contrary, to everyone's shame, is so far still new," the girl student instantly declared, simply lunging forward from her chair. "Besides, there are no innocent prejudices," she added bitterly.

"I just wanted to state," the high-school boy became terribly excited, "that although prejudices are, of course, old and need to be wiped out, yet concerning name days everybody already knows they're stupid and too old hat to waste precious time on, which has been wasted by the whole world even without that, so as to use one's wits for some object more in need of..."

"Too dragged out, can't understand a thing," the girl student shouted.

"It seems to me that everybody has the right to speak equally with everybody else, and if I wish to state my opinion, like anybody else, then..."

"No one is taking away your right to speak," the hostess herself now cut in sharply, "you are simply being invited to stop maundering, because no one can understand you."

"Allow me to observe, however, that you do not respect me; if I was unable to finish my thought, it's not from having no thoughts, but rather from an excess of thoughts..." the high-school boy muttered, all but in despair, and became finally confused.

"If you don't know how to talk, shut up," the girl student swatted.

The high-school boy even jumped on his chair.

"I just wished to state," he shouted, all burning with shame, and afraid to look around, "that you just wanted to pop up with your cleverness because Mr. Stavrogin came in—that's what!"

"Your thought is dirty and immoral, and indicates the utter insignificance of your development. I beg you not to advert to me again," the girl student rattled out.

"Stavrogin," the hostess began, "they were shouting about family rights just before you came—this officer here" (she nodded at her relative, the major). "And I'm most certainly not going to be the one to bother you with such old, long-disposed-of nonsense. All the same, where on earth could family rights and duties have come from, in the sense of the prejudice in which they now appear? That's the question. Your opinion?"

"What do you mean, where on earth?" Stavrogin asked in turn.

"That is, we know, for instance, that the prejudice about God originated in thunder and lightning," the girl student suddenly ripped out again, all but leaping on Stavrogin with her eyes. "It is known only too well that original mankind, being scared of thunder and lightning, deified the invisible enemy, feeling their weakness before him. But how did the prejudice about the family arise? Where on earth could the family itself have come from?"

"That is not quite the same..." the hostess tried to stop her.

"I suppose the answer to such a question would be immodest," Stavrogin answered.

"How's that?" the girl student lunged forward.

But a tittering came from the teachers' group, echoed at once from the other end by Lyamshin and the high-school boy, and followed by the husky guffaw of the major-relative.

"You should write vaudevilles," the hostess remarked to Stavrogin.

"That adverts all too little to your honor, whatever your name is," the girl student cut off in decided indignation.

"And you shouldn't pop up!" the major blurted out. "You are a young lady, you should behave modestly, and it's as if you're sitting on pins."

"Kindly keep still, and do not dare to address me familiarly with your nasty comparisons. It's the first time I've seen you and I care nothing about our family connection."

"But I'm your uncle! I used to tote you around in my arms when you were still an infant!"

"What do I care what you used to tote around. I didn't ask you to tote me around, which means, mister impolite officer, that you got pleasure from it. And allow me to remark that you dare not use a familiar tone with me, unless it's from civic feeling, and that I forbid it once and for all."

"They're all like that!" the major banged his fist on the table, addressing Stavrogin, who was sitting opposite him. "No, sir, excuse me, I like liberalism and modernity, and I like listening to intelligent conversation, but—mind you—from men. From women, from these modern dithery things—no, sir, it pains me! Don't you fidget!" he cried to the girl student, who was hopping up and down on her chair. "No, I demand to speak, too; I have been offended, sirs."

"You only hinder others, and can't say anything yourself," the hostess grumbled indignantly.

"No, I will have my say," the excited major addressed Stavrogin. "I'm counting on you, Mr. Stavrogin, as one who has only just arrived, though I do not have the honor of knowing you. Without men they'll perish like flies—that is my opinion. This whole woman question of theirs is just merely a lack of originality. I assure you that this whole woman question was invented for them by men, out of foolishness, and it has blown up in their faces—thank God I'm not married! Not the least diversity, sir, they cannot even invent a simple pattern; men even invent their patterns for them! Look here, sir, I used to carry her in my arms, danced the mazurka with her when she was ten years old, she came in today, naturally I flew to embrace her, and she announces to me from the second word that there is no God. If it had been from the third word, not from the second—but no, she's in a hurry! Well, suppose intelligent people don't believe, but that's from intelligence, and you, I say, squirt that you are, what do you understand about God? You were taught by some student, and if he'd taught you to light icon lamps, you'd do it."

"That's all lies, you are a very wicked man, and I conclusively expressed your groundlessness to you just now," the girl student replied disdainfully, as if scorning too many explanations with such a man. "I precisely told you just now that we were all taught by the catechesis: 'If you honor your father and your parents, you'll live a long life and be granted wealth.' It's in the ten commandments. [148]If God found it necessary to offer a reward for love, it means your God is immoral. These are the words in which I gave you my proof today, and not from the second word, but because you declared your rights. Whose fault is it if you're dumb and don't understand even now. You feel offended and you're angry—that's the whole clue to your generation."

"Ninny!" said the major.

"And you are a nincompoop."

"Go on, abuse me!"

"I beg your pardon, Kapiton Maximovich, but didn't you tell me that you yourself don't believe in God?" Liputin peeped from the other end of the table.

"What if I did, it's a different matter with me! Maybe I do believe, but not quite. Though I don't fully believe, still I'm not going to say that God should be shot. Back when I was serving with the hussars, I kept reflecting about God. It's an accepted fact in all poems that a hussar drinks and carouses; so, sir, maybe I did drink, but, would you believe, I used to jump out of bed in the middle of the night, just in my socks, and start crossing myself in front of the icon, asking God to send me faith, because even then I couldn't be at peace: is there God, or not? I really had a hot time of it! In the morning I'd get distracted, of course, and faith would seem to disappear again, and generally I've noticed that faith always disappears somewhat during the day."

"You wouldn't happen to have a deck of cards?" Verkhovensky, with a gaping yawn, addressed the hostess.

"I am altogether, altogether in sympathy with your question!" the girl student ripped out, aglow with indignation at the major's words.

"Precious time is being wasted listening to stupid talk," the hostess cut off, looking demandingly at her husband.

The girl student drew herself up.

"I wanted to declare to the meeting about the suffering and protest of the students, but since time is being wasted on immoral talk..."

"There's no such thing as moral or immoral!" the high-school boy could not bear it, once the girl student started.

"I knew that, mister high-school student, way before you were taught such things."

"And I maintain," the boy flew into a frenzy, "that you are a child come from Petersburg to enlighten us all, when we know it ourselves. About the commandment: 'Honor thy father and mother,' which you didn't know how to recite, and its being immoral—since Belinsky everyone in Russia has known that."

"Will this never end?" Madame Virginsky said determinedly to her husband. As hostess, she blushed at the worthlessness of the talk, especially when she noticed a few smiles and even some perplexity among the first-time visitors.

"Gentlemen," Virginsky suddenly raised his voice, "if anyone wished to begin on something more pertinent, or has something to state, I suggest he set about it without wasting time."

"I venture to make a question," the lame teacher, who had hitherto been silent and was sitting especially decorously, gently said. "I should like to know whether we here and now constitute some sort of meeting, or are a gathering of ordinary mortals who have come as guests? I ask more for the sake of order, and so as not to be in ignorance."

This "cunning" question produced its effect; everyone exchanged glances, each apparently expecting another to answer, and suddenly, as if on command, they all turned their eyes to Verkhovensky and Stavrogin.

"I simply suggest we vote on how to answer the question: 'Are we a meeting, or not?’“ said Madame Virginsky.

"I join fully in the suggestion," echoed Liputin, "though it is somewhat vague."

"I join, too." "So do I," came other voices.

"And it seems to me there would indeed be more order," Virginsky clinched.

"So, then, let's vote!" the hostess announced. "Lyamshin, I ask that you sit down at the piano: you can give your vote from there, when the voting starts."

"Again!" cried Lyamshin. "I've banged enough for you."

"I urgently ask you, sit down and play; don't you want to be of use to the cause?"

"But I assure you, Arina Prokhorovna, no one is eavesdropping. It's just your fantasy. And the windows are high, and, besides, who'd understand anything even if he was eavesdropping?"

"We don't understand what it's about ourselves," someone's voice grumbled.

"And I tell you that precaution is always necessary. It's in case there are spies," she turned to Verkhovensky with her interpretation, "let them hear from the street that we're having a party and music."

"Eh, the devil!" Lyamshin swore, sat down at the piano, and started banging out a waltz, striking the keys randomly and all but with his fists.

"I suggest that those who wish it to be a meeting raise their right hand," Madame Virginsky suggested.

Some raised their hand, others did not. There were some who raised it and then took it back. Took it back and then raised it again.

"Pah, the devil! I didn't understand a thing," one officer shouted.

"I don't either," shouted another.

"No, I understand," a third one shouted, "hand up if it's yes.”

"Yes, but what does yesmean?"

"It means a meeting."

"No, not a meeting."

"I voted a meeting," the high-school boy shouted, addressing Madame Virginsky.

"Then why didn't you raise your hand?"

"I kept looking at you, you didn't raise yours, so I didn't either."

"How stupid, it's because I made the suggestion, that's why I didn't raise mine. Gentlemen, I suggest we do it again the other way round: whoever wants a meeting can sit and not raise his hand, and whoever doesn't, raise his right hand."

"Whoever doesn't?" the high-school boy repeated.

"Are you doing it on purpose, or what?" Madame Virginsky shouted wrathfully.

"No, excuse me, is it whoever wants or whoever doesn't—because it needs to be defined more precisely," came two or three voices.

"Whoever does not, does not.”

"Very well, but what should one do, raise it or not raise it, if one does notwant?" shouted an officer.

"Ehh, we're not really used to a constitution yet," the major observed.

"Mr. Lyamshin, if you don't mind, you're pounding so that no one can hear anything," observed the lame teacher.

"But, by God, Arina Prokhorovna, nobody's eavesdropping," Lyamshin jumped up. "I simply don't want to play! I came here as a guest, not a banger on pianos!"

"Gentlemen," Virginsky suggested, "answer by voice: are we a meeting, or not?"

"A meeting, a meeting!" came from all sides.

"If so, there's no point in voting, it's enough. Is it enough, gentlemen, or need we also vote?"

"No need, no need, we understand!"

"Maybe there's someone who doesn't want a meeting?"

"No, no, we all want it."

"But what is a meeting?" shouted a voice. It went unanswered.

"We must elect a president," the shout came from all sides.

"Our host, certainly, our host!"

"If so, gentlemen," the elected Virginsky began, "then I suggest my original suggestion from earlier: if anyone wished to begin on something more pertinent, or has something to state, let him set about it without wasting time."

General silence. The eyes of all again turned to Stavrogin and Verkhovensky.

"Verkhovensky, do you have anything to state?" the hostess asked directly.

"Precisely nothing," he stretched himself, yawning, on his chair. "I would like a glass of cognac, though."

"Stavrogin, what about you?"

"Thanks, I don't drink."

"I'm asking whether or not you wish to speak, not about cognac."

"Speak? About what? No, I don't wish to."

"You'll get your cognac," she answered Verkhovensky.

The girl student stood up. She had already tried to jump up several times.

"I came to declare about the sufferings of the unfortunate students and about arousing them everywhere to protest ..."

But she stopped short; at the other end of the table another competitor had appeared, and all eyes turned to him. Long-eared Shigalyov, with a gloomy and sullen air, slowly rose from his seat and melancholically placed a fat notebook, filled with extremely small writing, on the table. He remained standing and was silent. Many looked at the notebook in bewilderment, but Liputin, Virginsky, and the lame teacher seemed pleased with something.

"I ask for the floor," Shigalyov declared sullenly but firmly.

"You have it," Virginsky permitted.

The orator sat down, was silent for about half a minute, then said in an important voice:

"Gentlemen..."

"Here's the cognac!" the relative who had been pouring tea chopped off squeamishly and scornfully, returning with the cognac and now setting it in front of Verkhovensky, along with a glass which she brought in her fingers without a tray or plate.

The interrupted orator paused with dignity.

"Never mind, go on, I'm not listening," cried Verkhovensky, filling his glass.

"Gentlemen, addressing myself to your attention," Shigalyov began again, "and, as you will see further on, requesting your assistance on a point of paramount importance, I must pronounce a preface."

"Arina Prokhorovna, have you got scissors?" Pyotr Stepanovich suddenly asked.

"What do you want scissors for?" she goggled her eyes at him.

"I forgot to cut my nails, it's three days now I've been meaning to cut them," he uttered, serenely studying his long and none-too-clean nails.