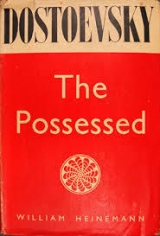

Текст книги "The Possessed"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 48 (всего у книги 49 страниц)

“Well, that's a good thing, that's capital!” he muttered in his bed. “I've been afraid all the time that we should go. Here it's so nice, better than anywhere. . . . You won't leave me? Oh, you have not left me!”

It was by no means so nice “here” however. He did not care to hear of her difficulties; his head was full of fancies and nothing else. He looked upon his illness as something transitory, a trifling ailment, and did not think about it at all; he though of nothing but how they would go and sell “these books.” He asked her to read him the gospel.

“I haven't read it for a long time ... in the original. Some one may ask me about it and I shall make a mistake; I ought to prepare myself after all.”

She sat down beside him and opened the book.

“You read beautifully,” he interrupted her after the first line. “I see, I see I was not mistaken,” he added obscurely but ecstatically. He was, in fact, in a continual state of enthusiasm She read the Sermon on the Mount.

“ Assez, assez, man enfant,enough. . . . Don't you think that thatis enough?”

And he closed his eyes helplessly. He was very weak, but had not yet lost consciousness. Sofya Matveyevna was getting up, thinking that he wanted to sleep. But he stopped her.

“My friend, I've been telling lies all my life. Even when I told the truth I never spoke for the sake of the truth, but always for my own sake. I knew it before, but I only see it now. . . . Oh, where are those friends whom I have insulted with my friendship all my life? And all, all! Savez-vous . . .perhaps I am telling lies now; no doubt I am telling lies now. The worst of it is that I believe myself when I am lying. The hardest thing in life is to live without telling lies . . . and without believing in one's lies. Yes, yes, that's just it. ... But wait a bit, that can all come afterwards. . . . We'll be together, together,” he added enthusiastically.

“Stepan Trofimovitch,” Sofya Matveyevna asked timidly, “hadn't I better send to the town for the doctor?”

He was tremendously taken aback.

“What for? Est-ce que je suis si malade? Mais rien de serieux.What need have we of outsiders? They may find, besides – and what will happen then? No, no, no outsiders and we'll be together.”

“Do you know,” he said after a pause, “read me something more, just the first thing you come across.”

Sofya Matveyevna opened the Testament and began reading.

“Wherever it opens, wherever it happens to open,” he repeated.

“'And unto the angel of the church of the Laodiceans . . .'”

“What's that? What is it? Where is that from?”

“It's from the R-Revelation.”

“ Oh, je m'en souviens, oui, l'Apocalypse. Lisez, lisez, Iam trying our future fortunes by the book. I want to know what has turned up. Read on from there. . . .”

“'And unto the angel of the church of the Laodiceans write: These things saith the Amen, the faithful and true witness, the beginning of the creation of God;

“'I know thy works, that thou art neither cold nor hot; I would thou wert cold or hot.

“'So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth.

“'Because thou sayest, I am rich and increased with goods, and have need of nothing: and thou knowest not that thou art wretched, and miserable, and poor, and blind, and naked.' “

“That too . . . and that's in your book too!” he exclaimed, with flashing eyes and raising his head from the pillow. “I never knew that grand passage! You hear, better be cold, better be cold than lukewarm, than onlylukewarm. Oh, I'll prove it! Only don't leave me, don't leave me alone! We'll prove it, we'll prove it!”

“I won't leave you, Stepan Trofimovitch. I'll never leave you!” She took his hand, pressed it in both of hers, and laid it against her heart, looking at him with tears in her eyes. (“I felt very sorry for him at that moment,” she said, describing it afterwards.)

His lips twitched convulsively.

“But, Stepan Trofimovitch, what are we to do though? Oughtn't we to let some of your friends know, or perhaps your relations?”

But at that he was so dismayed that she was very sorry that she had spoken of it again. Trembling and shaking, he besought her to fetch no one, not to do anything. He kept insisting, “No one, no one! We'll be alone, by ourselves, alone, nous partirons ensemble.”

Another difficulty was that the people of the house too began to be uneasy; they grumbled, and kept pestering Sofya Matveyevna. She paid them and managed to let them see her money. This softened them for the time, but the man insisted on seeing Stepan Trofimovitch's “papers.” The invalid pointed with a supercilious smile to his little bag. Sofya Matveyevna found in it the certificate of his having resigned his post at the university, or something of the kind, which had served him as a passport all his life. The man persisted, and said that “he must be taken somewhere, because their house wasn't a hospital, and if he were to die there might be a bother. We should have no end of trouble.” Sofya Matveyevna tried to speak to him of the doctor, but it appeared that sending to the town would cost so much that she had to give up all idea of the doctor. She returned in distress to her invalid. Stepan Trofimovitch was getting weaker and weaker.

“Now read me another passage. . . . About the pigs,” he said suddenly.

“What?” asked Sofya Matveyevna, very much alarmed. “About the pigs . . . that's there too . . . ces cochons. Iremember the devils entered into swine and they all were drowned. You must read me that; I'll tell you why afterwards. I want to remember it word for word. I want it word for word.”

Sofya Matveyevna knew the gospel well and at once found the passage in St. Luke which I have chosen as the motto of my record. I quote it here again:

“'And there was there one herd of many swine feeding on the mountain; and they besought him that he would suffer them to enter into them. And he suffered them.

“'Then went the devils out of the man and entered into the swine; and the herd ran violently down a steep place into the lake, and were choked.

“'When they that fed them saw what was done, they fled, and went and told it in the city and in the country.

“'Then they went out to see what was done; and came to Jesus and found the man, out of whom the devils were departed, sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed, and in his right mind; and they were afraid.'”

“My friend,” said Stepan Trofimovitch in great excitement “ savez-vous,that wonderful and . . . extraordinary passage has been a stumbling-block to me all my life . . . dans ce livre.... so much so that I remembered those verses from childhood. Now an idea has occurred to me; une comparaison.A great number of ideas keep coming into my mind now. You see, that's exactly like our Russia, those devils that come out of the sick man and enter into the swine. They are all the sores, all the foul contagions, all the impurities, all the devils great and small that have multiplied in that great invalid, our beloved Russia, in the course of ages and ages. Oui, cette Russie que j'aimais tou jours.But a great idea and a great Will will encompass it from on high, as with that lunatic possessed of devils . . . and all those devils will come forth, all the impurity, all the rottenness that was putrefying on the surface . . . and they will beg of themselves to enter into swine; and indeed maybe they have entered into them already! They are we, we and those . . . and Petrusha and les autres avec lui . . .and I perhaps at the head of them, and we shall cast ourselves down, possessed and raving, from the rocks into the sea, and we shall all be drowned – and a good thing too, for that is all we are fit for. But the sick man will be healed and 'will sit at the feet of Jesus,' and all will look upon him with astonishment. . . . My dear, vous comprendrez apres,but now it excites me very much. . . . Vous comprendrez apres. Nous comprendrons ensemble.”

He sank into delirium and at last lost consciousness. So it went on all the following day. Sofya Matveyevna sat beside him, crying. She scarcely slept at all for three nights, and avoided seeing the people of the house, who were, she felt, beginning to take some steps. Deliverance only came on the third day. In the morning Stepan Trofimovitch returned to consciousness, recognised her, and held out his hand to her. She crossed herself hopefully. He wanted to look out of the window. “ Tiens, un lac!” he said. “Good heavens, I had not seen it before! . . .” At that moment there was the rumble of a carriage at the cottage door and a great hubbub in the house followed.

III

It was Varvara Petrovna herself. She had arrived, with Darya Pavlovna, in a closed carriage drawn by four horses, with two footmen. The marvel had happened in the simplest way: Anisim, dying of curiosity, went to Varvara Petrovna's the day after he reached the town and gossiped to the servants, telling them he had met Stepan Trofimovitch alone in a village, that the latter had been seen by peasants walking by himself on the high road, and that he had set off for Spasov by way of Ustyevo accompanied by Sofya Matveyevna. As Varvara Petrovna was, for her part, in terrible anxiety and had done everything she could to find her fugitive friend, she was at once told about Anisim. When she had heard his story, especially the details of the departure for Ustyevo in a cart in the company of some Sofya Matvoyevna, she instantly got ready and set off post-haste for Ustyevo herself.

Her stern and peremptory voice resounded through the cottage; even the landlord and his wife were intimidated. She had only stopped to question them and make inquiries, being persuaded that Stepan Trofimovitch must have reached Spasov long before. Learning that he was still here and ill, she entered the cottage in great agitation.

“Well, where is he? Ah, that's you!” she cried, seeing Sofya Matveyevna, who appeared at that very instant in the doorway of the next room. “I can guess from your shameless face that it's you. Go away, you vile hussy! Don't let me find a trace of her in the house! Turn her out, or else, my girl, I'll get you locked up for good. Keep her safe for a time in another house. She's been in prison once already in the town; she can go back there again. And you, my good man, don't dare to let anyone in while I am here, I beg of you. I am Madame Stavrogin, and I'll take the whole house. As for you, my dear, you'll have to give me a full account of it all.”

The familiar sounds overwhelmed Stepan Trofimovitch. He began to tremble. But she had already stepped behind the screen. With flashing eyes she drew up a chair with her foot, and, sinking back in it, she shouted to Dasha:

“Go away for a time! Stay in the other room. Why are you so inquisitive? And shut the door properly after you.”

For some time she gazed in silence with a sort of predatory look into his frightened face.

“Well, how are you getting on, Stepan Trofimovitch? So you've been enjoying yourself?” broke from her with ferocious irony.

“ Chere,” Stepan Trofimovitch faltered, not knowing what he was saying, “I've learnt to know real life in Russia . . . et je precherai l'Evangile.”

“Oh, shameless, ungrateful man!” she wailed suddenly, clasping her hands. '' As though you had not disgraced me enough, you've taken up with . . . oh, you shameless old reprobate!”

“Chere . .

. ”

His voice failed him and he could not articulate a syllable but simply gazed with eyes wide with horror.

“Who is she?”

“ C'est un ange; c'etait plus qu'un ange pour moi.She's been all night . . . Oh, don't shout, don't frighten her, chere, chere...”

With a loud noise, Varvara Petrovna pushed back her chair, uttering a loud cry of alarm.

“Water, water!”

Though he returned to consciousness, she was still shaking with terror, and, with pale cheeks, looked at his distorted face. It was only then, for the first time, that she guessed the seriousness of his illness.

“Darya,” she whispered suddenly to Darya Pavlovna, “send at once for the doctor, for Salzfish; let Yegorytch go at once. Let him hire horses here and get another carriage from the town. He must be here by night.”

Dasha flew to do her bidding. Stepan Trofimovitch still gazed at her with the same wide-open, frightened eyes; his blanched lips quivered.

“Wait a bit, Stepan Trofimovitch, wait a bit, my dear!” she said, coaxing him like a child. “There, there, wait a bit! Darya will come back and ... My goodness, the landlady, the landlady, you come, anyway, my good woman!”

In her impatience she ran herself to the landlady.

“Fetch that womanback at once, this minute. Bring her back, bring her back!”

Fortunately Sofya Matveyevna had not yet had time to get away and was only just going out of the gate with her pack and her bag. She was brought back. She was so panic-stricken that she was trembling in every limb. Varvara Petrovna pounced on her like a hawk on a chicken, seized her by the hand and dragged her impulsively to Stepan Trofimovitch.

“Here, here she is, then. I've not eaten her. You thought I'd eaten her.”

Stepan Trofimovitch clutched Varvara Petrovna's hand, raised it to his eyes, and burst into tears, sobbing violently and convulsively.

“There, calm yourself, there, there, my dear, there, poor dear man'! Ach, mercy on us! Calm yourself, will you?” she shouted frantically. “Oh, you bane of my life!”

“My dear,” Stepan Trofimovitch murmured at last, addressing Sofya Matveyevna, “stay out there, my dear, I want to say something here. ...”

Sofya Matveyevna hurried out at once.

“ Cherie . . . cherie . ..”he gasped.

“Don't talk for a bit, Stepan Trofimovitch, wait a little till you've rested. Here's some water. Do wait, will you!”

She sat down on the chair again. Stepan Trofimovitch held her hand tight. For a long while she would not allow him to speak. He raised her hand to his lips and fell to kissing it. She set her teeth and looked away into the corner of the room.

“ Je vous aimais,” broke from him at last. She had never heard such words from him, uttered in such a voice.

“H'm!” she growled in response.

“ Je vous aimais toute ma vie . . . vingt ans!”

She remained silent for two or three minutes.

“And when you were getting yourself up for Dasha you sprinkled yourself with scent,” she said suddenly, in a terrible whisper.

Stepan Trofimovitch was dumbfoundered.

“You put on a new tie . . .”

Again silence for two minutes.

“Do you remember the cigar?”

“My friend,” he faltered, overcome with horror.

“That cigar at the window in the evening . . . the moon was shining . . . after the arbour ... at Skvoreshniki? Do you remember, do you remember?” She jumped up from her place, seized his pillow by the corners and shook it with his head on it. “Do you remember, you worthless, worthless, ignoble, cowardly, worthless man, always worthless!” she hissed in her furious whisper, restraining herself from speaking loudly. At last she left him and sank on the chair, covering her face with her hands. “Enough!” she snapped out, drawing herself up. “Twenty years have passed, there's no calling them back. I am a fool too.”

“ Je vous aimais.” He clasped his hands again.

“Why do you keep on with your aimaisand aimais?Enough!” she cried, leaping up again. “And if you don't go to sleep at once I'll ... You need rest; go to sleep, go to sleep at once, shut your eyes. Ach, mercy on us, perhaps he wants some lunch! What do you eat? What does he eat? Ach, mercy on us! Where is that woman? Where is she?”

There was a general bustle again. But Stepan Trofimovitch faltered in a weak voice that he really would like to go to sleep une heure,and then un bouillon, un the. . . . enfin il est si heureux.He lay back and really did seem to go to sleep (he probably pretended to). Varvara Petrovna waited a little, and stole out on tiptoe from behind the partition.

She settled herself in the landlady's room, turned out the landlady and her husband, and told Dasha to bring her that woman.There followed an examination in earnest.

“Tell me all about it, my good girl. Sit down beside me; that's right. Well?”

“I met Stepan Trofimovitch . . .”

“Stay, hold your tongue! I warn you that if you tell lies or conceal anything, I'll ferret it out. Well?”

“Stepan Trofimovitch and I ... as soon as I came to Hatovo . . .” Sofya Matveyevna began almost breathlessly.

“Stay, hold your tongue, wait a bit! Why do you gabble like that? To begin with, what sort of creature are you?”

Sofya Matveyevna told her after a fashion, giving a very brief account of herself, however, beginning with Sevastopol. Varvara Petrovna listened in silence, sitting up erect in her chair, looking sternly straight into the speaker's eyes.

“Why are you so frightened? Why do you look at the ground? I like people who look me straight in the face and hold their own with me. Go on.”

She told of their meeting, of her books, of how Stepan Trofimovitch had regaled the peasant woman with vodka . . . “That's right, that's right, don't leave out the slightest detail,” Varvara Petrovna encouraged her.

At last she described how they had set off, and how Stepan Trofimovitch had gone on talking, “really ill by that time,” and here had given an account of his life from the very beginning, talking for some hours. “Tell me about his life.”

Sofya Matveyevna suddenly stopped and was completely nonplussed.

“I can't tell you anything about that, madam,” she brought out, almost crying; “besides, I could hardly understand a word of it.”

“Nonsense! You must have understood something.”

“He told a long time about a distinguished lady with black hair.” Sofya Matveyevna flushed terribly though she noticed Varvara Petrovna's fair hair and her complete dissimilarity with the “brunette” of the story.

“Black-haired? What exactly? Come, speak!”

“How this grand lady was deeply in love with his honour all her life long and for twenty years, but never dared to speak, and was shamefaced before him because she was a very stout lady. . . .”

“The fool!” Varvara Petrovna rapped out thoughtfully but resolutely.

Sofya Matveyevna was in tears by now.

“I don't know how to tell any of it properly, madam, because I was in a great fright over his honour; and I couldn't understand, as he is such an intellectual gentleman.”

“It's not for a goose like you to judge of his intellect. Did he offer you his hand?”

The speaker trembled.

“Did he fall in love with you? Speak! Did he offer you his hand?” Varvara Petrovna shouted peremptorily.

“That was pretty much how it was,” she murmured tearfully. “But I took it all to mean nothing, because of his illness,” she added firmly, raising her eyes.

“What is your name?”

“Sofya Matveyevna, madam,”

“Well, then, let me tell you, Sofya Matveyevna, that he is a wretched and worthless little man. . . . Good Lord! Do you look upon me as a wicked woman '!”

Sofya Matveyevna gazed open-eyed.

“A wicked woman, a tyrant? Who has ruined his life?”

“How can that be when you are crying yourself, madam?”

Varvara Petrovna actually had tears in her eyes.

“Well, sit down, sit down, don't be frightened. Look me straight in the face again. Why are you blushing? Dasha, come here. Look at her. What do you think of her? Her heart is pure. . . .”

And to the amazement and perhaps still greater alarm of Sofya Matveyevna, she suddenly patted her on the cheek.

“It's only a pity she is a fool. Too great a fool for her age. That's all right, my dear, I'll look after you. I see that it's all nonsense. Stay near here for the time. A room shall be taken for you and you shall have food and everything else from me . . . till I ask for you.”

Sofya Matveyevna stammered in alarm that she must hurry on.

“You've no need to hurry. I'll buy all your books, and meantime you stay here. Hold your tongue; don't make excuses. If I hadn't come you would have stayed with him all the same, wouldn't you?”

“I wouldn't have left him on any account,” Sofya Matveyevna brought out softly and firmly, wiping her tears.

It was late at night when Doctor Salzfish was brought. He was a very respectable old man and a practitioner of fairly wide experience who had recently lost his post in the service in consequence of some quarrel on a point of honour with his superiors. Varvara Petrovna instantly and actively took him under her protection. He examined the patient attentively, questioned him, and cautiously pronounced to Varvara Petrovna that “the sufferer's” condition was highly dubious in consequence of complications, and that they must be prepared “even for the worst.” Varvara Petrovna, who had during twenty years get accustomed to expecting nothing serious or decisive to come from Stepan Trofimovitch, was deeply moved and even turned pale. “Is there really no hope?”

“Can there ever be said to be absolutely no hope? But ...” She did not go to bed all night, and felt that the morning would never come. As soon as the patient opened his eyes and returned to consciousness (he was conscious all the time, however, though he was growing weaker every hour), she went up to him with a very resolute air.

“Stepan Trofimovitch, one must be prepared for anything. I've sent for a priest. You must do what is right. . . .”

Knowing his convictions, she was terribly afraid of his refusing. He looked at her with surprise.

“Nonsense, nonsense!” she vociferated, thinking he was already refusing. “This is no time for whims. You have played the fool enough.”

“But ... am I really so ill, then?”

He agreed thoughtfully. And indeed I was much surprised to learn from Varvara Petrovna afterwards that he showed no fear of death at all. Possibly it was that he simply did not believe it, and still looked upon his illness as a trifling one.

He confessed and took the sacrament very readily. Every one, Sofya Matveyevna, and even the servants, came to congratulate him on taking the sacrament. They were all moved to tears looking at his sunken and exhausted face and his blanched and quivering lips.

“ Oui, mes amis,and I only wonder that you . . . take so much trouble. I shall most likely get up to-morrow, and we will . . . set off. . . . Toute cette ceremonie . . .for which, of course, I feel every proper respect . . . was ...”

“I beg you, father, to remain with the in valid,” said Varvara Petrovna hurriedly, stopping the priest, who had already taken off his vestments. “As soon as tea has been handed, I beg you to begin to speak of religion, to support his faith.”

The priest spoke; every one was standing or sitting round the sick-bed.

“In our sinful days,” the priest began smoothly, with a cup of tea in his hand, “faith in the Most High is the sole refuge of the race of man in all the trials and tribulations of life, as well as its hope for that eternal bliss promised to the righteous.”

Stepan Trofimovitch seemed to revive, a subtle smile strayed on his lips.

“ Man pere, je vous remercie et vous etes bien bon, mais . ..”

“No maisabout it, no maisat all!” exclaimed Varvara Petrovna, bounding up from her chair. “Father,” she said, addressing the priest, “he is a man who . . . he is a man who . . . You will have to confess him again in another hour! That's the sort of man he is.”

Stepan Trofimovitch smiled faintly.

“My friends,” he said, “God is necessary to me, if only because He is the only being whom one can love eternally.”

Whether he was really converted, or whether the stately ceremony of the administration of the sacrament had impressed him and stirred the artistic responsiveness of his temperament or not, he firmly and, I am told, with great feeling uttered some words which were in flat contradiction with many of his former convictions.

“My immortality is necessary if only because God will not be guilty of injustice and extinguish altogether the flame of love for Him once kindled in my heart. And what is more precious than love? Love is higher than existence, love is the crown of existence; and how is it possible that existence should not be under its dominance? If I have once loved Him and rejoiced in my love, is it possible that He should extinguish me and my joy and bring me to nothingness again? If there is a God, then I am immortal. Voila ma profession de foi.”

“There is a God, Stepan Trofimovitch, I assure you there is,” Varvara Petrovna implored him. “Give it up, drop all your foolishness for once in your life!” (I think she had not quite understood his profession de foi.)

“My friend,” he said, growing more and more animated, though his voice broke frequently, “as soon as I understood . . . that turning of the cheek, I ... understood something else as well. J'ai menti toute ma vie,all my life, all! I should like . . . but that will do to-morrow. . . . To-morrow we will all set out.”

Varvara Petrovna burst into tears. He was looking about for some one.

“Here she is, she is here!” She seized Sofya Matveyevna by the hand and led her to him. He smiled tenderly.

“Oh, I should dearly like to live again!” he exclaimed with an extraordinary rush of energy. “Every minute, every instant of life ought to be a blessing to man . . . they ought to be, they certainly ought to be! It's the duty of man to make it so; that's the law of his nature, which always exists even if hidden. . . . Oh, I wish I could see Petrusha . . . and all of them . . . Shatov ...”

I may remark that as yet no one had heard of Shatov's fate – not Varvara Petrovna nor Darya Pavlovna, nor even Salzfish, who was the last to come from the town.

Stepan Trofimovitch became more and more excited, feverishly so, beyond his strength.

“The mere fact of the ever present idea that there exists something infinitely more just and more happy than I am fills me through and through with tender ecstasy – and glorifies me – oh, whoever I may be, whatever I have done! What is far more essential for man than personal happiness is to know and to believe at every instant that there is somewhere a perfect and serene happiness for all men and for everything. . . . The one essential condition of human existence is that man should always be able to bow down before something infinitely great. If men are deprived of the infinitely great they will not go on living and will die of despair. The Infinite and the Eternal are as essential for man as the little planet on which he dwells. My friends, all, all: hail to the Great Idea! The Eternal, Infinite Idea! It is essential to every man, whoever he may be, to bow down before what is the Great Idea. Even the stupidest man needs something great. Petrusha . . . oh, how I want to see them all again! They don't know, they don't know that that same Eternal, Grand Idea lies in them all!”

Doctor Salzfish was not present at the ceremony. Coming in suddenly, he was horrified, and cleared the room, insisting that the patient must not be excited.

Stepan Trofimovitch died three days later, but by that time he was completely unconscious. He quietly went out like a candle that is burnt down. After having the funeral service performed, Varvara Petrovna took the body of her poor friend to Skvoreshniki. His grave is in the precincts of the church and is already covered with a marble slab. The inscription and the railing will be added in the spring.

Varvara Petrovna's absence from town had lasted eight days. Sofya Matveyevna arrived in the carriage with her and seems to have settled with her for good. I may mention that as soon as Stepan Trofimovitch lost consciousness (the morning that he received the sacrament) Varvara Petrovna promptly asked Sofya Matveyevna to leave the cottage again, and waited on the invalid herself unassisted to the end, but she sent for her at once when he had breathed his last. Sofya Matveyevna was terribly alarmed by Varvara Petrovna's proposition, or rather command, that she should settle for good at Skvoreshniki, but the latter refused to listen to her protests.

“That's all nonsense! I will go with you to sell the gospel. I have no one in the world now.”

“You have a son, however,” Salzfish observed.

“I have no son!” Varvara Petrovna snapped out – and it was like a prophecy.

Last updated on Wed Jan 12 09:26:22 2011 for eBooks@Adelaide.