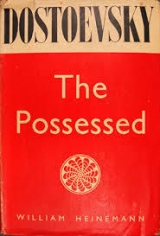

Текст книги "The Possessed"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 49 страниц)

“Nicolas, may I bring Pyotr Stepanovitch in to see you?” she asked, in a soft and restrained voice, trying to make out her son's face behind the lamp.

“You can – you can, of course you can,” Pyotr Stepanovitch himself cried out, loudly and gaily. He opened the door with his hand and went in.

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch had not heard the knock at the door, and only caught his mother's timid question, and had not had time to answer it. Before him, at that moment, there lay a letter he had just read over, which he was pondering deeply. He started, hearing Pyotr Stepanovitch's sudden outburst, and hurriedly put the letter under a paper-weight, but did not quite succeed; a corner of the letter and almost the whole envelope showed.

“I called out on purpose that you might be prepared,” Pyotr Stepanovitch said hurriedly, with surprising naivete, running up to the table, and instantly staring at the corner of the letter, which peeped out from beneath the paper-weight.

“And no doubt you had time to see how I hid the letter I had just received, under the paper-weight,” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch calmly, without moving from his place.

“A letter? Bless you and your letters, what are they to do with me?” cried the visitor. “But . . . what does matter ...” he whispered again, turning to the door, which was by now closed, and nodding his head in that direction.

“She never listens,” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch observed coldly.

“What if she did overhear?” cried Pyotr Stepanovitch, raising his voice cheerfully, and settling down in an arm-chair. “I've nothing against that, only I've come here now to speak to you alone. Well, at last I've succeeded in getting at you. First of all, how are you? I see you're getting on splendidly. To-morrow you'll show yourself again – eh?”

“Perhaps.”

“Set their minds at rest. Set mine at rest at last.” He gesticulated violently with a jocose and amiable air. “If only you knew what nonsense I've had to talk to them. You know, though.” He laughed.

“I don't know everything. I only heard from my mother that you've been . . . very active.”

” Oh, well, I've said nothing definite,” Pyotr Stepanovitch flared up at once, as though defending himself from an awful attack. “I simply trotted out Shatov's wife; you know, that is, the rumours of your liaison in Paris, which accounted, of course, for what happened on Sunday. You're not angry?”

“I'm sure you've done your best.”

“Oh, that's just what I was afraid of. Though what does that mean, 'done your best'? That's a reproach, isn't it? You always go straight for things, though. . . . What I was most afraid of, as I came here, was that you wouldn't go straight for the point.”

“I don't want to go straight for anything,” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch with some irritation– But he laughed at once.

“I didn't mean that, I didn't mean that, don't make a mistake,” cried Pyotr Stepanovitch, waving his hands, rattling his words out like peas, and at once relieved at his companion's irritability. “I'm not going to worry you with ourbusiness, especially in your present position. I've only come about Sunday's affair, and only to arrange the most necessary steps, because, you see, it's impossible. I've come with the frankest explanations which I stand in more need of than you – so much for your vanity, but at the same time it's true. I've come to be open with you from this time forward.”

“Then you have not been open with me before?”

“You know that yourself. I've been cunning with you many times . . . you smile; I'm very glad of that smile as a prelude to our explanation. I provoked that smile on purpose by using the word 'cunning,' so that you might get cross directly at my daring to think I could be cunning, so that I might have a chance of explaining myself at once. You see, you see how open I have become now! Well, do you care to listen?”

In the expression of Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch's face, which was contemptuously composed, and even ironical, in spite of his visitor's obvious desire to irritate him by the insolence of his premeditated and intentionally coarse naivetes, there was, at last, a look of rather uneasy curiosity.

“Listen,” said Pyotr Stepanovitch, wriggling more than ever, “when I set off to come here, I mean here in the large sense, to this town, ten days ago, I made up my mind, of course, to assume a character. It would have been best to have done without anything, to have kept one's own character, wouldn't it? There is no better dodge than one's own character, because no one believes in it. I meant, I must own, to assume the part of a fool, because it is easier to be a fool than to act one's own character; but as a fool is after all something extreme, and anything extreme excites curiosity, I ended by sticking to my own character. And what is my own character? The golden mean: neither wise nor foolish, rather stupid, and dropped from the moon, as sensible people say here, isn't that it?”

“Perhaps it is,” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch, with a faint smile.

“Ah, you agree – I'm very glad; I knew beforehand that it was your own opinion. . . . You needn't trouble, I am not annoyed, and I didn't describe myself in that way to get a flattering contradiction from you – no, you're not stupid, you're clever. ... Ah! you're smiling again! . . . I've blundered once more. You would not have said 'you're clever,' granted; I'll let it pass anyway. Passons,as papa says, and, in parenthesis, don't be vexed with my verbosity. By the way, I always say a lot, that is, use a great many words and talk very fast, and I never speak well. And why do I use so many words, and why do I never speak well? Because I don't know how to speak. People who can speak well, speak briefly. So that I am stupid, am I not? But as this gift of stupidity is natural to me, why shouldn't I make skilful use of it? And I do make use of it. It's true that as I came here, I did think, at first, of being silent. But you know silence is a great talent, and therefore incongruous for me, and secondly silence would be risky, anyway. So I made up my mind finally that it would be best to talk, but to talk stupidly – that is, to talk and talk and talk – to be in a tremendous hurry to explain things, and in the end to get muddled in my own explanations, so that my listener would walk away without hearing the end, with a shrug, or, better still, with a curse. You succeed straight off in persuading them of your simplicity, in boring them and in being incomprehensible – three advantages all at once! Do you suppose anybody will suspect you of mysterious designs after that? Why, every one of them would take it as a personal affront if anyone were to say I had secret designs. And I sometimes amuse them too, and that's priceless. Why, they're ready to forgive me everything now, just because the clever fellow who used to publish manifestoes out there turns out to be stupider than themselves – that's so, isn't it? From your smile I see you approve.”

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch was not smiling at all, however.

On the contrary, he was listening with a frown and some impatience.

“Eh? What? I believe you said 'no matter.' “

Pyotr Stepanovitch rattled on. (Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch had said nothing at all.) “Of course, of course. I assure you I'm not here to compromise you by my company, by claiming you as my comrade. But do you know you're horribly captious to-day; I ran in to you with a light and open heart, and you seem to be laying up every word I say against me. I assure you I'm not going to begin about anything shocking to-day, I give you my word, and I agree beforehand to all your conditions.”

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch was obstinately silent.

“Eh? What? Did you say something? I see, I see that I've made a blunder again, it seems; you've not suggested conditions and you're not going to; I believe you, I believe you; well, you can set your mind at rest; I know, of course, that it's not worth while for me to suggest them, is it? I'll answer for you beforehand, and – just from stupidity, of course; stupidity again. . . . You're laughing? Eh? What?”

“Nothing,” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch laughed at last. “I just remembered that I really did call you stupid, but you weren't there then, so they must have repeated it. ... I would ask you to make haste and come to the point.”

“Why, but I am at the point! I am talking about Sunday,” babbled Pyotr Stepanovitch. “Why, what was I on Sunday? What would you call it? Just fussy, mediocre stupidity, and in the stupidest way I took possession of the conversation by force. But they forgave me everything, first because I dropped from the moon, that seems to be settled here, now, by every one; and, secondly, because I told them a pretty little story, and got you all out of a scrape, didn't they, didn't they?”

“That is, you told your story so as to leave them in doubt and suggest some compact and collusion between us, when there was no collusion and I'd not asked you to do anything.”

“Just so, just so!” Pyotr Stepanovitch caught him up, apparently delighted. “That's just what I did do, for I wanted you to see that I implied it; I exerted myself chiefly for your sake, for I caught you and wanted to compromise you, above all I wanted to find out how far you're afraid.”

“It would be interesting to know why you are so open now?”

“Don't be angry, don't be angry, don't glare at me. . . . You're not, though. You wonder why I am so open? Why, just because it's all changed now; of course, it's over, buried Under the sand. I've suddenly changed my ideas about you. The old way is closed; now I shall never compromise you in the old way, it will be in a new way now.”

“You've changed your tactics?”

“There are no tactics. Now it's for you to decide in everything, that is, if you want to, say yes, and if you want to, say no. There you have my new tactics. And I won't say a word about our cause till you bid me yourself. You laugh? Laugh away. I'm laughing myself. But I'm in earnest now, in earnest, in earnest, though a man who is in such a hurry is stupid, isn't he? Never mind, I may be stupid, but I'm in earnest, in earnest.”

He really was speaking in earnest in quite a different tone, and with a peculiar excitement, so that Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch looked at him with curiosity.

“You say you've changed your ideas about me?” he asked.

“I changed my ideas about you at the moment when you drew your hands back after Shatov's attack, and, that's enough, that's enough, no questions, please, I'll say nothing more now.”

He jumped up, waving his hands as though waving off questions. But as there were no questions, and he had no reason to go away, he sank into an arm-chair again, somewhat reassured.

“By the way, in parenthesis,” he rattled on at once, “some people here are babbling that you'll kill him, and taking bets about it, so that Lembke positively thought of setting the police on, but Yulia Mihailovna forbade it. ... But enough about that, quite enough, I only spoke of it to let you know. By the way, I moved the Lebyadkins the same day, you know; did you get my note with their address?”

“I received it at the time.”

“I didn't do that by way of 'stupidity.' I did it genuinely, to serve you. If it was stupid, anyway, it was done in good faith.”

“Oh, all right, perhaps it was necessary. . . .” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch dreamily, “only don't write any more letters to me, I beg you.”

“Impossible to avoid it. It was only one.”

“So Liputin knows?”

“Impossible to help it: but Liputin, you know yourself, dare not . . . By the way, you ought to meet our fellows, that is, thefellows not ourfellows, or you'll be finding fault again. Don't disturb yourself, not just now, but sometime. Just now it's raining. I'll let them know, they'll meet together, and we'll go in the evening. They're waiting, with their mouths open like young crows in a nest, to see what present we've brought them. They're a hot-headed lot. They've brought out leaflets, they're on the point of quarrelling. Virginsky is a universal humanity man, Liputin is a Fourierist with a marked inclination for police work; a man, I assure you, who is precious from one point of view, though he requires strict supervision in all others; and, last of all, that fellow with the long ears, he'll read an account of his own system. And do you know, they're offended at my treating them casually, and throwing cold water over them, but we certainly must meet.”

“You've made me out some sort of chief?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch dropped as carelessly as possible.

Pyotr Stepanovitch looked quickly at him.

“By the way,” he interposed, in haste to change the subject, as though he had not heard. “I've been here two or three times, you know, to see her excellency, Varvara Petrovna, and I have been obliged to say a great deal too.”

“So I imagine.”

“No, don't imagine, I've simply told her that you won't kill him, well, and other sweet things. And only fancy; the very next day she knew I'd moved Marya Timofyevna beyond the river. Was it you told her?”

“I never dreamed of it!”

“I knew it wasn't you. Who else could it be? It's interesting.”

“Liputin, of course.”

“N-no, not Liputin,” muttered Pyotr Stepanovitch, frowning; “I'll find out who. It's more like Shatov. . . . That's nonsense though. Let's leave that! Though it's awfully important. . . . By the way, I kept expecting that your mother would suddenly burst out with the great question. . . . Ach! yes, she was horribly glum at first, but suddenly, when I came to-day, she was beaming all over, what does that mean?”

“It's because I promised her to-day that within five days I'll be engaged to Lizaveta Nikolaevna,” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch said with surprising openness.

“Oh! . . . Yes, of course,” faltered Pyotr Stepanovitch, seeming disconcerted. “There are rumours of her engagement, you know. It's true, too. But you're right, she'd run from under the wedding crown, you've only to call to her. You're not angry at my saying so?”

“No, I'm not angry.”

“I notice it's awfully hard to make you angry to-day, and I begin to be afraid of you. I'm awfully curious to know how you'll appear to-morrow. I expect you've got a lot of things ready. You're not angry at my saying so?”

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch made no answer at all, which completed Pyotr Stepanovitch's irritation.

“By the way, did you say that in earnest to your mother, about Lizaveta Nikolaevna?” he asked.

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch looked coldly at him.

“Oh, I understand, it was only to soothe her, of course.”

“And if it were in earnest?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch asked firmly.

“Oh, God bless you then, as they say in such cases. It won't hinder the cause (you see, I don't say 'our,' you don't like the word 'our') and I ... well, I ... am at your service, as you know.”

“You think so?”

“I think nothing – nothing,” Pyotr Stepanovitch hurriedly declared, laughing, “because I know you consider what you're about beforehand for yourself, and everything with you has been thought out. I only mean that I am seriously at your service, always and everywhere, and in every sort of circumstance, every sort really, do you understand that?”

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch yawned.

“I've bored you,” Pyotr Stepanovitch cried, jumping up suddenly, and snatching his perfectly new round hat as though he were going away. He remained and went on talking, however, though he stood up, sometimes pacing about the room and tapping himself on the knee with his hat at exciting parts of the conversation.

“I meant to amuse you with stories of the Lembkes, too,” he cried gaily.

“Afterwards, perhaps, not now. But how is Yulia Mihailovna?”

“What conventional manners all of you have! Her health is no more to you than the health of the grey cat, yet you ask after it. I approve of that. She's quite well, and her respect for you amounts to a superstition, her immense anticipations of you amount to a superstition. She does not say a word about what happened on Sunday, and is convinced that you will overcome everything yourself by merely making your appearance. Upon my word! She fancies you can do anything. You're an enigmatic and romantic figure now, more than ever you were – extremely advantageous position. It is incredible how eager every one is to see you. They were pretty hot when I went away, but now it is more so than ever. Thanks again for your letter. They are all afraid of Count K. Do you know they look upon you as a spy? I keep that up, you're not angry?”

“It does not matter.”

“It does not matter; it's essential in the long run. They have their ways of doing things here. I encourage it, of course; Yulia Mihailovna, in the first place, Gaganov too. . . . You laugh? But you know I have my policy; I babble away and suddenly I say something clever just as they are on the look-out for it. They crowd round me and I humbug away again. They've all given me up in despair by now: 'he's got brains but he's dropped from the moon.' Lembke invites me to enter the service so that I may be reformed. You know I treat him mockingly, that is, I compromise him and he simply stares, Yulia Mihailovna encourages it. Oh, by the way, Gaganov is in an awful rage with you. He said the nastiest things about you yesterday at Duhovo. I told him the whole truth on the spot, that is, of course, not the whole truth. I spent the whole day at Duhovo. It's a splendid estate, a fine house.”

“Then is he at Duhovo now?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch broke in suddenly, making a sudden start forward and almost leaping up from his seat.

“No, he drove me here this morning, we returned together,” said Pyotr Stepanovitch, appearing not to notice Stavrogin's momentary excitement. “What's this? I dropped a book.” He bent down to pick up the “keepsake” he had knocked down. The Women of Balzac,' with illustrations.” He opened it suddenly. “I haven't read it. Lembke writes novels too.”

“Yes?” queried Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch, as though beginning to be interested.

“In Russian, on the sly, of course, Yulia Mihailovna knows and allows it. He's henpecked, but with good manners; it's their system. Such strict form – such self-restraint! Something of the sort would be the thing for us.”

“You approve of government methods?”

“I should rather think so! It's the one thing that's natural and practicable in Russia. ... I won't ... I won't,” he cried out suddenly, “I'm not referring to that – not a word on delicate subjects. Good-bye, though, you look rather green.”

“I'm feverish.”

“I can well believe it; you should go to bed. By the way, there are Skoptsi here in the neighbourhood – they're curious people ... of that later, though. Ah, here's another anecdote. There's an infantry regiment here in the district. I was drinking last Friday evening with the officers. We've three friends among them, vous comprenez?They were discussing atheism and I need hardly say they made short work of God. They were squealing with delight. By the way, Shatov declares that if there's to be a rising in Russia we must begin with atheism. Maybe it's true. One grizzled old stager of a captain sat mum, not saying a word. All at once he stands up in the middle of the' room and says aloud, as though speaking to himself: 'If there's no God, how can I be a captain then?' He took up His cap and went out, flinging up his hands.”

“He expressed a rather sensible idea,” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch, yawning for the third time.

“Yes? I didn't understand it; I meant to ask you about it. Well what else have I to tell you? The Shpigulin factory's interesting; as you know, there are five hundred workmen in it, it's a hotbed of cholera, it's not been cleaned for fifteen years and the factory hands are swindled. The owners are millionaires. I assure you that some among the hands have an idea of the Internationale,.What, you smile? You'll see – only give me ever so little time! I've asked you to fix the time already and now I ask you again and then. . . . But I beg your pardon, I won't, I won't speak of that, don't frown. There!” He turned back suddenly. “I quite forgot the chief thing. I was told just now that our box had come from Petersburg.”

“You mean ...” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch looked at him, not understanding.

“Your box, your things, coats, trousers, and linen have come. Is it true?”

“Yes . . . they said something about it this morning.”

“Ach, then can't I open it at once! . . .”

“Ask Alexey.”

“Well, to-morrow, then, will to-morrow do? You see my new jacket, dress-coat and three pair's of trousers are with your things, from Sharmer's, by your recommendation, do you remember?”

“I hear you're going in for being a gentleman here,” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch with a smile. “Is it true you're going to take lessons at the riding school?”

Pyotr Stepanovitch smiled a wry smile. “I say,” he said suddenly, with excessive haste in a voice that quivered and faltered, “I say, Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch, let's drop personalities once for all. Of course, you can despise me as much as you like if it amuses you – but we'd better dispense with personalities for a time, hadn't we?”

“All right,” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch assented.

Pyotr Stepanovitch grinned, tapped his knee with his hat, shifted from one leg to the other, and recovered his former expression.

“Some people here positively look upon me as your rival with Lizaveta Nikolaevna, so I must think of my appearance, mustn't I,” he laughed. “Who was it told you that though? H'm. It's just eight o'clock; well I must be off. I promised to look in on Varvara Petrovna, but I shall make my escape. And you go to bed and you'll be stronger to-morrow. It's raining and dark, but I've a cab, it's not over safe in the streets here at night. . . . Ach, by the way, there's a run-away convict from Siberia, Fedka, wandering about the town and the neighbourhood. Only fancy, he used to be a serf of mine, and my papa sent him for a soldier fifteen years ago and took the money for him. He's a very remarkable person.”

“You have been talking to him?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch scanned him.

“I have. He lets me know where he is. He's ready for anything, anything, for money of course, but he has convictions, too, of a sort, of course. Oh yes, by the way, again, if you meant anything of that plan, you remember, about Lizaveta Nikolaevna, I tell you once again, I too am a fellow ready for anything of any kind you like, and absolutely at your service. ... Hullo! are you reaching for your stick. Oh no ... only fancy ... I thought you were looking for your stick.”

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch was looking for nothing and said nothing.

But he had risen to his feet very suddenly with a strange look in his face.

“If you want any help about Mr. Gaganov either,” Pyotr Stepanovitch blurted out suddenly, this time looking straight at the paper-weight, “of course I can arrange it all, and I'm certain you won't be able to manage without me.”

He went out suddenly without waiting for an answer, but thrust his head in at the door once more. “I mention that,” he gabbled hurriedly, “because Shatov had no right either, you know, to risk his life last Sunday when he attacked you, had he? I should be glad if you would make a note of that.” He disappeared again without waiting for an answer.

IV

Perhaps he imagined, as he made his exit, that as soon as he was left alone, Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch would begin beating on the wall with his fists, and no doubt he would have been glad to see this, if that had been possible. But, if so, he was greatly mistaken. Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch was still calm. He remained standing for two minutes in the same position by the table, apparently plunged in thought, but soon a cold and listless smile came on to his lips. He slowly sat down again in the same place in the corner of the sofa, and shut his eyes as though from weariness. The corner of the letter was still peeping from under the paperweight, but he didn't even move to cover it.

He soon sank into complete forgetfulness.

When Pyotr Stepanovitch went out without coming to see her, as he had promised, Varvara Petrovna, who had been worn out by anxiety during these days, could not control herself, and ventured to visit her son herself, though it was not her regular time. She was still haunted by the idea that he would tell her something conclusive. She knocked at the door gently as before, and again receiving no answer, she opened the door. Seeing that Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch was sitting strangely motionless, she cautiously advanced to the sofa with a throbbing heart. She seemed struck by the fact that he could fall asleep so quickly and that he could sleep sitting like that, so erect and motionless, so that his breathing even was scarcely perceptible. His face was pale and forbidding, but it looked, as it were, numb and rigid. His brows were somewhat contracted and frowning. He positively had the look of a lifeless wax figure. She stood over him for about three minutes, almost holding her breath, and suddenly she was seized with terror. She withdrew on tiptoe, stopped at the door, hurriedly made the sign of the cross over him, and retreated unobserved, with a new oppression and a new anguish at her heart.

He slept a long while, more than an hour, and still in the same rigid pose: not a muscle of his face twitched, there was not the faintest movement in his whole body, and his brows were still contracted in the same forbidding frown. If Varvara Petrovna had remained another three minutes she could not have endured the stifling sensation that this motionless lethargy roused in her, and would have waked him. But he suddenly opened his eyes, and sat for ten minutes as immovable as before, staring persistently and curiously, as though at some object in the corner which had struck him, although there was nothing new or striking in the room.

Suddenly there rang out the low deep note of the clock on the wall.

With some uneasiness he turned to look at it, but almost at the same moment the other door opened, and the butler, Alexey Yegorytch came in. He had in one hand a greatcoat, a scarf, and a hat, and in the other a silver tray with a note on it.

“Half-past nine,” he announced softly, and laying the other things on a chair, he held out the tray with the note – a scrap of paper unsealed and scribbled in pencil. Glancing through it, Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch took a pencil from the table, added a few words, and put the note back on the tray.

“Take it back as soon as I have gone out, and now dress me,” he said, getting up from the sofa.

Noticing that he had on a light velvet jacket, he thought a minute, and told the man to bring him a cloth coat, which he wore on more ceremonious occasions. At last, when he was dressed and had put on his hat, he locked the door by which his mother had come into the room, took the letter from under the paperweight, and without saying a word went out into the corridor, followed by Alexey Yegorytch. From the corridor they went down the narrow stone steps of the back stairs to a passage which opened straight into the garden. In the corner stood a lantern and a big umbrella.

“Owing to the excessive rain the mud in the streets is beyond anything,” Alexey Yegorytch announced, making a final effort to deter his master from the expedition. But opening his umbrella the latter went without a word into the damp and sodden garden, which was dark as a cellar. The wind was roaring and tossing the bare tree-tops. The little sandy paths were wet and slippery. Alexey Yegoryvitch walked along as he was, bareheaded, in his swallow-tail coat, lighting up the path for about three steps before them with the lantern.

“Won't it be noticed?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch asked suddenly.

“Not from the windows. Besides I have seen to all that already,” the old servant answered in quiet and measured tones.

“Has my mother retired?”

“Her excellency locked herself in at nine o'clock as she has done the last few days, and there is no possibility of her knowing anything. At what hour am I to expect your honour?”

“At one or half-past, not later than two.”

“Yes, sir.”

Crossing the garden by the winding paths that they both knew by heart, they reached the stone wall, and there in the farthest corner found a little door, which led out into a narrow and deserted lane, and was always kept locked. It appeared that Alexey Yegorytch had the key in his hand.

“Won't the door creak?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch inquired again.

But Alexey Yegorytch informed him that it had been oiled yesterday “as well as to-day.” He was by now wet through. Unlocking the door he gave the key to Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch.

“If it should be your pleasure to be taking a distant walk, I would warn your honour that I am not confident of the folk here, especially in the back lanes, and especially beyond the river,” he could not resist warning him again. He was an old servant, who had been like a nurse to Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch, and at one time used to dandle him in his arms; he was a grave and severe man who was fond of listening to religious discourse and reading books of devotion.

“Don't be uneasy, Alexey Yegorytch.”

“May God's blessing rest on you, sir, but only in your righteous undertakings.”

“What?” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch, stopping short in the lane.

Alexey Yegorytch resolutely repeated his words. He had never before ventured to express himself in such language in his master's presence.

Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch locked the door, put the key in his pocket, and crossed the lane, sinking five or six inches into the mud at every step. He came out at last into a long deserted street. He knew the town like the five fingers of his hand, but Bogoyavlensky Street was a long way off. It was past ten when he stopped at last before the locked gates of the dark old house that belonged to Filipov. The ground floor had stood empty since the Lebyadkins had left it, and the windows were boarded up, but there was a light burning in Shatov's room on the second floor. As there was no bell he began banging on the gate with his hand. A window was opened and Shatov peeped out into the street. It was terribly dark, and difficult to make out anything. Shatov was peering out for some time, about a minute.