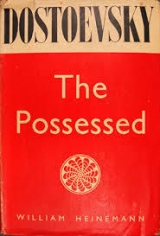

Текст книги "The Possessed"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 49 страниц)

“You always say witty things, and sleep in peace satisfied with what you've said, but that's how you damage yourself.”

“Blum, I have just convinced myself that it's quite a mistake, quite a mistake.”

“Not from the words of that false, vicious young man whom you suspect yourself? He has won you by his flattering praise of your talent for literature.”

“Blum, you understand nothing about it; your project is absurd, I tell you. We shall find nothing and there will be a fearful upset and laughter too, and then Yulia Mihailovna . . .”

” We shall .certainly find everything we are looking for.” Blum advanced firmly towards him, laying his right hand on his heart. “We will make a search suddenly early in the morning, carefully showing every consideration for the person himself and strictly observing all the prescribed forms of the law. The young men, Lyamshin and Telyatnikov, assert positively that we shall find all we want. They were constant visitors there. Nobody is favourably disposed to Mr. Verhovensky. Madame Stavrogin has openly refused him her graces, and every honest man, if only there is such a one in this coarse town, is persuaded that a hotbed of infidelity and social doctrines has always been concealed there. He keeps all the forbidden books, Ryliev's. 'Reflections,' all. Herzen's works. ... I have an approximate catalogue, in case of need.”

“Oh heavens! Every one has these books; how simple you are, my poor Blum.”

“And many manifestoes,” Blum went on without heeding the observation. “We shall end by certainly coming upon traces of the real manifestoes here. That young Verhovensky I feel very suspicious of.”

“But you are mixing up the father and the son. They are not on good terms. The son openly laughs at his father.”

“That's only a mask.”

“Blum, you've sworn to torment me! Think! he is a conspicuous figure here, after all. He's been a professor, he is a well-known man. He'll make such an uproar and there will be such gibes all over the town, and we shall make a mess of it all. . . . And only think how Yulia Mihailovna will take it.” Blum pressed forward and did not listen. “He was only a lecturer, only a lecturer, and of a low rank when he retired.” He smote himself on the chest. “He has no marks of distinction. He was discharged from the service on suspicion of plots against the government. He has been under secret supervision, and undoubtedly still is so. And in view of the disorders that have come to light now, you are undoubtedly bound in duty. You are losing your chance of distinction by letting slip the real criminal.”

“Yulia Mihailovna! Get away, Blum,” Von Lembke cried suddenly, hearing the voice of his spouse in the next room. Blum started but did not give in.

“Allow me, allow me,” he persisted, pressing both hands still more tightly on his chest.

“Get away!” hissed Andrey Antonovitch. “Do what you like . . . afterwards. Oh, my God!”

The curtain was raised and Yulia Mihailovna made her appearance. She stood still majestically at the sight of Blum, casting a haughty and offended glance at him, as though the very presence of this man was an affront to her. Blum respectfully made her a deep bow without speaking and, doubled up with veneration, moved towards the door on tiptoe with his arms held a little away from him.

Either because he really took Andrey Antonovitch's last hysterical outbreak as a direct permission to act as he was asking, or whether he strained a point in this case for the direct advantage of his benefactor, because he was too confident that success would crown his efforts; anyway, as we shall see later on, this conversation of the governor with his subordinate led to a very surprising event which amused many people, became public property, moved Yulia Mihailovna to fierce anger, utterly disconcerting Andrey Antonovitch and reducing him at the crucial moment to a state of deplorable indecision.

It was a busy day for Pyotr Stepanovitch. From Von Lembke he hastened to Bogoyavlensky Street, but as he went along Bykovy Street, past the house where Karmazinov was staying,” he suddenly stopped, grinned, and went into the house. The servant told him that he was expected, which interested him, as he had said nothing beforehand of his coming.

But the great writer really had been expecting him, not only that day but the day before and the day before that. Three days before he had handed him his manuscript Merci(which . he had meant to read at the literary matinee at Yulia Mihailovna's fete). He had done this out of amiability, fully convinced that he was agreeably nattering the young man's vanity by letting him read the great work beforehand. Pyotr Stepanovitch had noticed long before that this vainglorious, spoiled gentleman, who was so offensively unapproachable for all but the elect, this writer “with the intellect of a statesman,” was simply trying to curry favour with him, even with avidity. I believe the young man guessed at last that Karmazinov considered him, if not the leader of the whole secret revolutionary movement in Russia, at least one of those most deeply initiated into the secrets of the Russian revolution who had an incontestable influence on the younger generation. The state of mind of “the cleverest man in Russia” interested Pyotr Stepanovitch, but hitherto he had, for certain reasons, avoided explaining himself.

The great writer was staying in the house belonging to his sister, who was the wife of a kammerherrand had an estate in the neighbourhood. Both she and her husband had the deepest reverence for their illustrious relation, but to their profound regret both of them happened to be in Moscow at the time of his visit, so that the honour of receiving him fell to the lot of an old lady, a poor relation of the kammerherr's, who had for years lived in the family and looked after the housekeeping. All the household had moved about on tiptoe since Karmazinov's arrival. The old lady sent news to Moscow almost every day, how he had slept, what he had deigned to eat, and had once sent a telegram to announce that after a dinner-party at the mayor's he was obliged to take a spoonful of a well-known medicine. She rarely plucked up courage to enter his room, though he behaved courteously to her, but dryly, and only talked to her of what was necessary.

When Pyotr Stepanovitch came in, he was eating his morning cutlet with half a glass of red wine. Pyotr Stepanovitch had been to see him before and always found him eating this cutlet, which he finished in his presence without ever offering him anything. After the cutlet a little cup of coffee was served. The footman who brought in the dishes wore a swallow-tail coat, noiseless boots, and gloves.

“Ha ha!” Karmazinov got up from the sofa, wiping his mouth with a table-napkin, and came forward to kiss him with an air of unmixed delight – after the characteristic fashion of Russians if they are very illustrious. But Pyotr Stepanovitch knew by experience that, though Karmazinov made a show of kissing him, he really only proffered his cheek, and so this time he did the same: the cheeks met. Karmazinov did not show that he noticed it, sat down on the sofa, and affably offered Pyotr Stepanovitch an easy chair facing him, in which the latter stretched himself at once.

“You don't . . . wouldn't like some lunch?” inquired Karmazinov, abandoning his usual habit but with an air, of course, which would prompt a polite refusal. Pyotr Stepanovitch at once expressed a desire for lunch. A shade of offended surprise darkened the face of his host, but only for an instant; he nervously rang for the servant and, in spite of all his breeding, raised his voice scornfully as he gave orders for a second lunch to be served.

“What will you have, cutlet or coffee?” he asked once more,

“A cutlet and coffee, and tell him to bring some more wine, I am hungry,” answered Pyotr Stepanovitch, calmly scrutinising his host's attire. Mr. Karmazinov was wearing a sort of indoor wadded jacket with pearl buttons, but it was too short, which was far from becoming to his rather comfortable stomach and the solid curves of his hips. But tastes differ. Over his knees he had a checkered woollen plaid reaching to the floor, though it was warm in the room.

“Are you unwell?” commented Pyotr Stepanovitch.

“No, not unwell, but I am afraid of being so in this climate,” answered the writer in his squeaky voice, though he uttered each word with a soft cadence and agreeable gentlemanly lisp. “I've been expecting you since yesterday.”

“Why? I didn't say I'd come.”

“No, but you have my manuscript. Have you . . . read it?”

“Manuscript? Which one?”

Karmazinov was terribly surprised.

“But you've brought it with you, haven't you?” He was so disturbed that he even left off eating and looked at Pyotr Stepanovitch with a face of dismay.

“Ah, that Bon jouryou mean. ...”

“ Merci.”

“Oh, all right. I'd quite forgotten it and hadn't read it; I haven't had time. I really don't know, it's not in my pockets . . . it must be on my table. Don't be uneasy, it will be found.”

“No, I'd better send to your rooms at once. It might be lost; besides, it might be stolen.”

“Oh, who'd want it! But why are you so alarmed? Why, Yulia Mihailovna told me you always have several copies made – one kept at a notary's abroad, another in Petersburg, a third in Moscow, and then you send some to a bank, I believe.”

“But Moscow might be burnt again and my manuscript with it. No, I'd better send at once.”

“Stay, here it is!” Pyotr Stepanovitch pulled a roll of note-paper out of a pocket at the back of his coat. “It's a little crumpled. Only fancy, it's been lying there with my pocket-handkerchief ever since I took it from you; I forgot it.”

Karmazinov greedily snatched the manuscript, carefully examined it, counted the pages, and laid it respectfully beside him on a special table, for the time, in such a way that he would not lose sight of it for an instant.

“You don't read very much, it seems?” he hissed, unable to restrain himself.

“No, not very much.”

“And nothing in the way of Russian literature?”

“In the way of Russian literature? Let me see, I have read something. ... 'On the Way' or 'Away!' or 'At the Parting of the Ways'– something of the sort; I don't remember. It's a long time since I read it, five years ago. I've no time.”

A silence followed.

“When I came I assured every one that you were a very intelligent man, and now I believe every one here is wild over you.”

“Thank you,” Pyotr Stepanovitch answered calmly.

Lunch was brought in. Pyotr Stepanovitch pounced on the cutlet with extraordinary appetite, had eaten it in a trice, tossed off the wine and swallowed his coffee.

“This boor,” thought Karmazinov, looking at him askance as he munched the last morsel and drained the last drops – “this boor probably understood the biting taunt in my words . . . and no doubt he has read the manuscript with eagerness; he is simply lying with some object. But possibly he is not lying and is only genuinely stupid. I like a genius to be rather stupid. Mayn't he be a sort of genius among them? Devil take the fellow!”

He got up from the sofa and began pacing from one end of the room to the other for the sake of exercise, as he always did after lunch.

“Leaving here soon?” asked Pyotr Stepanovitch from his easy chair, lighting a cigarette.

“I really came to sell an estate and I am in the hands of my bailiff.”

“You left, I believe, because they expected an epidemic out there after the war?”

“N-no, not entirely for that reason,” Mr. Karmazinov went on, uttering his phrases with an affable intonation, and each time he turned round in pacing the corner there was a faint but jaunty quiver of his right leg. “I certainly intend to live as long as I can.” He laughed, not without venom. “There is something in our Russian nobility that makes them wear out very quickly, from every point of view. But I wish to wear out as late as possible, and now I am going abroad for good; there the climate is better, the houses are of stone, and everything stronger. Europe will last my time, I think. What do you think?”

“How can I tell?”

“H'm. If the Babylon out there really does fall, and great will be the fall thereof (about which I quite agree with you, yet I think it will last my time), there's nothing to fall here in Russia, comparatively speaking. There won't be stones to fall, everything will crumble into dirt. Holy Russia has less power of resistance than anything in the world. The Russian peasantry is still held together somehow by the Russian God; but according to the latest accounts the Russian God is not to be relied upon, and scarcely survived the emancipation; it certainly gave Him a severe shock. And now, what with railways, what with you . . . I've no faith in the Russian God.”

“And how about the European one?”

“I don't believe in any. I've been slandered to the youth of Russia. I've always sympathised with every movement among them. I was shown the manifestoes here. Every one looks at them with perplexity because they are frightened at the way things are put in them, but every one is convinced of their power even if they don't admit it to themselves. Everybody has been rolling downhill, and every one has known for ages that they have nothing to clutch at. I am persuaded of the success of this mysterious propaganda, if only because Russia is now pre-eminently the place in all the world where anything you like may happen without any opposition. I understand only too well why wealthy Russians all flock abroad, and more and more so every year. It's simply instinct. If the ship is sinking, the rats are the first to leave it. Holy Russia is a country of wood, of poverty . . . and of danger, the country of ambitious beggars in its upper classes, while the immense majority live in poky little huts. She will be glad of any way of escape; you have only to present it to her. It's only the government that still means to resist, but it brandishes its cudgel in the dark and hits its own men. Everything here is doomed and awaiting the end. Russia as she is has no future. I have become a German and I am proud of it.”

“But you began about the manifestoes. Tell me everything: how do you look at them?”

“Every one is afraid of them, so they must be influential. They openly unmask what is false and prove that there is nothing to lay hold of among us, and nothing to lean upon. They speak aloud while all is silent. What is most effective about them (in spite of their style) is the incredible boldness with which they look the truth straight in the face. To look facts straight in the face is only possible to Russians of this generation. No, in Europe they are not yet so bold; it is a realm of stone, there there is still something to lean upon. So far as I see and am able to judge, the whole essence of the Russian revolutionary idea lies in the negation of honour. I like its being so boldly and fearlessly expressed. No, in Europe they wouldn't understand it yet, but that's just what we shall clutch at. For a Russian a sense of honour is only a superfluous burden, and it always has been a burden through all his history. The open 'right to dishonour “will attract him more than anything. I belong to the older generation and, I must confess, still cling to honour, but only from habit. It is only that I prefer the old forms, granted it's from timidity; you see one must live somehow what's left of one's life.”

He suddenly stopped.

“I am talking,” he thought, “while he holds his tongue and watches me. He has come to make me ask him a direct question. And I shall ask him.”

“Yulia Mihailovna asked me by some stratagem to find out from you what the surprise is that you are preparing for the ball to-morrow,” Pyotr Stepanovitch asked suddenly.

“Yes, there really will be a surprise and I certainly shall astonish . . .” said Karmazinov with increased dignity. “But I won't tell you what the secret is.”

Pyotr Stepanovitch did not insist.

“There is a young man here called Shatov,” observed the great writer. “Would you believe it, I haven't seen him.”

“A very nice person. What about him?”

“Oh, nothing. He talks about something. Isn't he the person who gave Stavrogin that slap in the face?”

“Yes.”

“And what's your opinion of Stavrogin?”

“I don't know; he is such a flirt.”

Karmazinov detested Stavrogin because it was the latter s habit not to take any notice of him.

“That flirt,” he said, chuckling, “if what is advocated in your manifestoes ever comes to pass, will be the first to be hanged.”

“Perhaps before,” Pyotr Stepanovitch said suddenly.

“Quite right too,” Karmazinov assented, not laughing, and with pronounced gravity.

“You have said so once before, and, do you know, I repeated it to him.”

“What, you surely didn't repeat it?” Karmazinov laughed again.

“He said that if he were to be hanged it would be enough for you to be flogged, not simply as a compliment but to hurt, as they flog the peasants.”

Pyotr Stepanovitch took his hat and got up from his seat. Karmazinov held out both hands to him at parting.

“And what if all that you are . . . plotting for is destined to come to pass . . .” he piped suddenly, in a honeyed voice with a peculiar intonation, still holding his hands in his. “How soon could it come about?”

“How could I tell?” Pyotr Stepanovitch answered rather roughly. They looked intently into each other's eyes.

“At a guess? Approximately?” Karmazinov piped still more sweetly.

“You'll have time to sell your estate and time to clear out too,” Pyotr Stepanovitch muttered still more roughly. They looked at one another even more intently.

There was a minute of silence.

“It will begin early next May and will be over by October,” Pyotr Stepanovitch said suddenly.

“I thank you sincerely,” Karmazinov pronounced in a voice saturated with feeling, pressing his hands.

“You will have time to get out of the ship, you rat,” Pyotr Stepanovitch was thinking as he went out into the street. “Well, if that 'imperial intellect' inquires so confidently of the day and the hour and thanks me so respectfully for the information I have given, we mustn't doubt of ourselves. [He grinned.] H'm! But he really isn't stupid . . . and he is simply a rat escaping; men like that don't tell tales!”

He ran to Filipov's house in Bogoyavlensky Street.

VI

Pyotr Stepanovitch went first to Kirillov's. He found him, as usual, alone, and at the moment practising gymnastics, that is, standing with his legs apart, brandishing his arms above his head in a peculiar way. On the floor lay a ball. The tea stood cold on the table, not cleared since breakfast. Pyotr Stepanovitch stood for a minute on the threshold.

“You are very anxious about your health, it seems,” he said in a loud and cheerful tone, going into the room. “What a jolly ball, though; foo, how it bounces! Is that for gymnastics too?”

Kirillov put on his coat.

“Yes, that's for the good of my health too,” he muttered dryly. “Sit down.”

“I'm only here for a minute. Still, I'll sit down. Health is all very well, but I've come to remind you of our agreement. The appointed time is approaching ... in a certain sense,” he concluded awkwardly.

“What agreement?”

“How can you ask?” Pyotr Stepanovitch was startled and even dismayed.

“It's not an agreement and not an obligation. I have not bound myself in any way; it's a mistake on your part.”

“I say, what's this you're doing?” Pyotr Stepanovitch jumped up.

“What I choose.”

“What do you choose?”

“The same as before.”

“How am I to understand that? Does that mean that you are in the same mind?”

“Yes. Only there's no agreement and never has been, and I have not bound myself in any way. I could do as I like and I can still do as I like.”

Kirillov explained himself curtly and contemptuously.

“I agree, I agree; be as free as you like if you don't change your mind.” Pyotr Stepanovitch sat down again with a satisfied air. “You are angry over a word. You've become very irritable of late; that's why I've avoided coming to see you, I was quite sure, though, you would be loyal.”

“I dislike you very much, but you can be perfectly sure – though I don't regard it as loyalty and disloyalty.”

“But do you know” (Pyotr Stepanovitch was startled again) “we must talk things over thoroughly again so as not to get in a muddle. The business needs accuracy, and you keep giving me such shocks. Will you let me speak?”

“Speak,” snapped Kirillov, looking away.

“You made up your mind long ago to take your life ... I mean, you had the idea in your mind. Is that the right expression? Is there any mistake about that?”

“I have the same idea still.”

“Excellent. Take note that no one has forced it on you.”

“Rather not; what nonsense you talk.”

“I dare say I express it very stupidly. Of course, it would be very stupid to force anybody to it. I'll go on. You were a member of the society before its organisation was changed, and confessed it to one of the members.”

“I didn't confess it, I simply said so.”

“Quite so. And it would be absurd to confess such a thing. What a confession! You simply said so. Excellent.”

“No, it's not excellent, for you are being tedious. I am not obliged to give you any account of myself and you can't understand my ideas. I want to put an end to my life, because that's my idea, because I don't want to be afraid of death, because . . . because there's no need for you to know. What do you want? Would you like tea? It's cold. Let me get you another glass.”

Pyotr Stepanovitch actually had taken up the teapot and was looking for an empty glass. Kirillov went to the cupboard and brought a clean glass.

“I've just had lunch at Karmazinov's,” observed his visitor, “then I listened to him talking, and perspired and .got into a sweat again running here. I am fearfully thirsty.”

“Drink. Cold tea is good.”

Kirillov sat down on his chair again and again fixed his eyes on the farthest corner.

“The idea had arisen in the society,” he went on in the same voice, “that I might be of use if I killed myself, and that when you get up some bit of mischief here, and they are looking for the guilty, I might suddenly shoot myself and leave a letter saying I did it all, so that you might escape suspicion for another year.”

“For a few days, anyway; one day is precious.”

“Good. So for that reason they asked me, if I would, to wait. I said I'd wait till the society fixed the day, because it makes no difference to me.”

“Yes, but remember that you bound yourself not to make up your last letter without me and that in Russia you would be at my . . . well, at my disposition, that is for that purpose only. I need hardly say, in everything else, of course, you are free,” Pyotr Stepanovitch added almost amiably.

“I didn't bind myself, I agreed, because it makes no difference to me.”

“Good, good. I have no intention of wounding your vanity, but . . .”

“It's not a question of vanity.”

“But remember that a hundred and twenty thalers were collected for your journey, so you've taken money.”

“Not at all.” Kirillov fired up. “The money was not on that condition. One doesn't take money for that.”

“People sometimes do.”

“That's a lie. I sent a letter from Petersburg, and in Petersburg I paid you a hundred and twenty thalers; I put it in your hand . . . and it has been sent off there, unless you've kept it for yourself.”

“All right, all right, I don't dispute anything; it has been sent off. Allthat matters is that you are still in the same mind.”

“Exactly the same. When you come and tell me it's time, I'll carry it all out. Will it be very soon?”

“Not very many days. . . . But remember, we'll make up the letter together, the same night.”

“The same day if you like. You say I must take the responsibility for the manifestoes on myself?”

“And something else too.”

“I am not going to make myself out responsible for everything.”

“What won't you be responsible for?” said Pyotr Stepanovitch again.

“What I don't choose; that's enough. I don't want to talk about it any more.”

Pyotr Stepanovitch controlled himself and changed the subject.

“To speak of something else,” he began, “will you be with us this evening? It's Virginsky's name-day; that's the pretext for our meeting.”

“I don't want to.”

“Do me a favour. Do come. You must. We must impress them by our number and our looks. You have a face . . . well, in one word, you have a fateful face.”

“You think so?” laughed Kirillov. “Very well, I'll come, but not for the sake of my face. What time is it?”

“Oh, quite early, half-past six. And, you know, you can go in, sit down, and not speak to any one, however many there may be there. Only, I say, don't forget to bring pencil and paper with you.”

“What's that for?”

“Why, it makes no difference to you, and it's my special request. You'll only have to sit still, speaking to no one, listen, and sometimes seem to make a note. You can draw something, if you like.”

“What nonsense! What for?”

“Why, since it makes no difference to you! You keep saying that it's just the same to you.”

“No, what for?”

“Why, because that member of the society, the inspector, has stopped at Moscow and I told some of them here that possibly the inspector may turn up to-night; and they'll think that you are the inspector. And as you've been here three weeks already, they'll be still more surprised.”

“Stage tricks. You haven't got an inspector in Moscow.”

“Well, suppose I haven't – damn him!– what business is that of yours and what bother will it be to you? You are a member of the society yourself.”

“Tell them I am the inspector; I'll sit still and hold my tongue, but I won't have the pencil and paper.”

“But why?”

“I don't want to.”

Pyotr Stepanovitch was really angry; he turned positively green, but again he controlled himself. He got up and took his hat.

“Is that fellow with you?” he brought out suddenly, in a low voice.

“Yes.”

“That's good. I'll soon get him away. Don't be uneasy.”

“I am not uneasy. He is only here at night. The old woman is in the hospital, her daughter-in-law is dead. I've been alone for the last two days. I've shown him the place in the paling where you can take a board out; he gets through, no one sees.”

“I'll take him away soon.”

“He says he has got plenty of places to stay the night in.”

“That's rot; they are looking for him, but here he wouldn't be noticed. Do you ever get into talk with him?”

“Yes, at night. He abuses you tremendously. I've been reading the 'Apocalypse' to him at night, and we have tea. He listened eagerly, very eagerly, the whole night.”

“Hang it all, you'll convert him to Christianity!”

“He is a Christian as it is. Don't be uneasy, he'll do the murder. Whom do you want to murder?”

“No, I don't want him for that, I want him for something different. . . . And does Shatov know about Pedka?”

“I don't talk to Shatov, and I don't see him.”

“Is he angry?”

“No, we are not angry, only we shun one another. We lay too long side by side in America.”

“I am going to him directly.”

“As you like.”

“Stavrogin and I may come and see you from there, about ten o'clock.”

“Do.”

“I want to talk to him about something important. . . . I say, make me a present of your ball; what do you want with it now? I want it for gymnastics too. I'll pay you for it if you like.”

“You can take it without.”

Pyotr Stepanovitch put the ball in the back pocket of his coat.

“But I'll give you nothing against Stavrogin,” Kirillov muttered after his guest, as he saw him out. The latter looked at him in amazement but did not answer.

Kirillov's last words perplexed Pyotr Stepanovitch extremely; he had not time yet to discover their meaning, but even while he was on the stairs of Shatov's lodging he tried to remove all trace of annoyance and to assume an amiable expression. Shatov was at home and rather unwell. He was lying on his bed, though dressed.

“What bad luck!” Pyotr Stepanovitch cried out in the doorway. “Are you really ill?”

The amiable expression of his face suddenly vanished; there was a gleam of spite in his eyes.

“Not at all.” Shatov jumped up nervously. “I am not ill at all ... a little headache . . .”

He was disconcerted; the sudden appearance of such a visitor positively alarmed him.

“You mustn't be ill for the job I've come about,” Pyotr Stepanovitch began quickly and, as it were, peremptorily. “Allow me to sit down.” (He sat down.) “And you sit down again on your bedstead; that's right. There will be a party of our fellows at Virginsky's to-night on the pretext of his birthday; it will have no political character, however – we've seen to that. I am coming with Nikolay Stavrogin. I would not, of course, have dragged you there, knowing your way of thinking at present . . . simply to save your being worried, not because we think you would betray us. But as things have turned out, you will have to go. You'll meet there the very people with whom we shall finally settle how you are to leave the society and to whom you are to hand over what is in your keeping. We'll do it without being noticed; I'll take you aside into a corner; there'll be a lot of people and there's no need for every one to know. I must confess I've had to keep my tongue wagging on your behalf; but now I believe they've agreed, on condition you hand over the printing press and all the papers, of course. Then you can go where you please.”

Shatov listened, frowning and resentful. The nervous alarm of a moment before had entirely left him.

“I don't acknowledge any sort of obligation to give an account to the devil knows whom,” he declared definitely. “No one has the authority to set me free.”

“Not quite so. A great deal has been entrusted to you. You hadn't the right to break off simply. Besides, you made no clear statement about it, so that you put them in an ambiguous position.”

“I stated my position clearly by letter as soon as I arrived here.”

“No, it wasn't clear,” Pyotr Stepanovitch retorted calmly. “I sent you 'A Noble Personality' to be printed here, and meaning the copies to be kept here till they were wanted; and the two manifestoes as well. You returned them with an ambiguous letter which explained nothing.”