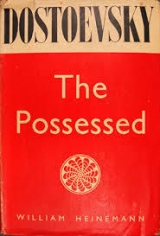

Текст книги "The Possessed"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 46 (всего у книги 49 страниц)

He was in agonies, trembling at the necessity of action and his own indecision. At last he took up the candle and again approached the door with the revolver held up in readiness; he put his left hand, in which he held the candle, on the doorhandle. But he managed awkwardly: the handle clanked, there was a rattle and a creak. “He will fire straightway,” flashed through Pyotr Stepanovitch's mind. With his foot he flung the door open violently, raised the candle, and held out the revolver; but no shot nor cry came from within. . . . There was no one in the room.

He started. The room led nowhere. There was no exit, no means of escape from it. He lifted the candle higher and looked about him more attentively: there was certainly no one. He called Kirillov's name in a low voice, then again louder; no one answered.

“Can he have got out by the window?” The casement in one window was, in fact, open. “Absurd! He couldn't have got away through, the casement.” Pyotr Stepanovitch crossed the room and went up to the window. “He couldn't possibly.” All at once he turned round quickly and was aghast at something extraordinary.

Against the wall facing the windows on the right of the door stood a cupboard. On the right side of this cupboard, in the corner formed by the cupboard and the wall, stood Kirillov, and he was standing in a very strange way; motionless, perfectly erect, with his arms held stiffly at his sides, his head raised and pressed tightly back against the wall in the very corner, he seemed to be trying to conceal and efface himself. Everything seemed to show that he was hiding, yet somehow it was not easy to believe it. Pyotr Stepanovitch was standing a little sideways to the corner, and could only see the projecting parts of the figure. He could not bring himself to move to the left to get a full view of Kirillov and solve the mystery. His heart began beating violently, and he felt a sudden rush of blind fury: he started from where he stood, and, shouting and stamping with his feet, he rushed to the horrible place.

But when he reached Kirillov he stopped short again, still more overcome, horror-stricken. What struck him most was that, in spite of his shout and his furious rush, the figure did riot stir, did not move in a single limb – as though it were of stone or of wax. The pallor of the face was unnatural, the black eyes were quite unmoving and were staring away at a point in the distance. Pyotr Stepanovitch lowered the candle and raised it again, lighting up the figure from all points of view and scrutinising it. He suddenly noticed that, although Kirillov was looking straight before him, he could see him and was perhaps watching him out of the corner of his eye. Then the idea occurred to him to hold the candle right up to the wretch's face, to scorch him and see what he would do. He suddenly fancied that Kirillov's chin twitched and that something like a mocking smile passed over his lips – as though he had guessed Pyotr Stepanovitch's thought. He shuddered arid, beside himself, clutched violently at Kirillov's shoulder.

Then something happened so hideous and so soon over that Pyotr Stepanovitch could never afterwards recover a coherent impression of it. He had hardly touched Kirillov when the latter bent down quickly and with his head knocked the candle out of Pyotr Stepanovitch's hand; the candlestick fell with a clang on the ground and the candle went out. At the same moment he was conscious of a fearful pain in the little finger of his left hand. He cried out, and all that he could remember was that, beside himself, he hit out with all his might and struck three blows with the revolver on the head of Kirillov, who had bent down to him and had bitten his finger. At last he tore away his finger and rushed headlong to get out of the house, feeling his way in the dark. He was pursued by terrible shouts from the room.

“Directly, directly, directly, directly.” Ten times. But he still ran on, and was running into the porch when he suddenly heard a loud shot. Then he stopped short in the dark porch and stood deliberating for five minutes; at last he made his way back into the house. But he had to get the candle. He had only to feel on the floor on the right of the cupboard for the candlestick; but how was he to light the candle? There suddenly came into his mind a vague recollection: he recalled that when he had run into the kitchen the day before to attack Fedka he had noticed in passing a large red box of matches in a corner on a shelf. Feeling with his hands, he made his way to the door on the left leading to the kitchen, found it, crossed the passage, and went down the steps. On the shelf, on the very spot where he had just recalled seeing it, he felt in the dark a full unopened box of matches. He hurriedly went up the steps again without striking a light, and it was only when he was near the cupboard, at the spot where he had struck Kirillov with the revolver and been bitten by him, that he remembered his bitten finger, and at the same instant was conscious that it was unbearably painful. Clenching his teeth, he managed somehow to light the candle-end, set it in the candlestick again, and looked about him: near the open casement, with his feet towards the right-hand corner, lay the dead body of Kirillov. The shot had been fired at the right temple and the bullet had come out at the top on the left, shattering the skull. There were splashes of blood and brains. The revolver was still in the suicide's hand on the floor. Death must have been instantaneous. After a careful look round, Pyotr Stepanovitch got up and went out on tiptoe, closed the door, left the candle on the table in the outer room, thought a moment, and resolved not to put it out, reflecting that it could not possibly set fire to anything. Looking once more at the document left on the table, he smiled mechanically and then went out of the house, still for some reason walking on tiptoe. He crept through Fedka's hole again and carefully replaced the posts after him.

III

Precisely at ten minutes to six Pyotr Stepanovitch and Erkel were walking up and down the platform at the railway-station beside a rather long train. Pyotr Stepanovitch was setting oft and Erkel was saying good-bye to him. The luggage was in, and his bag was in the seat he had taken in a second-class carriage. The first bell had rung already; they were waiting for the second. Pyotr Stepanovitch looked about him, openly watching the passengers as they got into the train. But he did not meet anyone he knew well; only twice he nodded to acquaintances – a merchant whom he knew slightly, and then a young village priest who was going to his parish two stations away. Erkel evidently wanted to speak of something of importance in the last moments, though possibly he did not himself know exactly of what, but he could not bring himself to begin! He kept fancying that Pyotr Stepanovitch seemed anxious to get rid of him and was impatient for the last bell.

“You look at every one so openly,” he observed with some timidity, as though he would have warned him.

“Why not? It would not do for me to conceal myself at present. It's too soon. Don't be uneasy. All I am afraid of is that the devil might send Liputin this way; he might scent me out and race off here.”

“Pyotr Stepanovitch, they are not to be trusted,” Erkel brought out resolutely. “Liputin?”

“None of them, Pyotr Stepanovitch.”

“Nonsense! they are all bound by what happened yesterday. There isn't one who would turn traitor. People won't go to certain destruction unless they've lost their reason.”

“Pyotr Stepanovitch, but they will lose their reason.” Evidently that idea had already occurred to Pyotr Stepanovitch too, and so Erkel's observation irritated him the more.

“You are not in a funk too, are you, Erkel? I rely on you more than on any of them. I've seen now what each of them is worth. Tell them to-day all I've told you. I leave them in your charge. Go round to each of them this morning. Read them my written instructions to-morrow, or the day after, when you are all together and they are capable of listening again . . . and believe me, they will be by to-morrow, for they'll be in an awful funk, and that will make them as soft as wax. . . . The great thing is that you shouldn't be downhearted.”

“Ach, Pyotr Stepanovitch, it would be better if you weren't going away.”

“But I am only going for a few days; I shall be back in no time.”

“Pyotr Stepanovitch,” Erkel brought out warily but resolutely, “what if you were going to Petersburg? Of course, I understand that you are only doing what's necessary for the cause.”

“I expected as much from you, Erkel. If you have guessed that I am going to Petersburg you can realise that I couldn't tell them yesterday, at that moment, that I was going so far for fear of frightening them. You saw for yourself what a state they were in. But you understand that I am going for the cause, for work of the first importance, for the common cause, and not to save my skin, as Liputin imagines.”

“Pyotr Stepanovitch, what if you were going abroad? I should understand ... I should understand that you must be careful of yourself because you are everything and we are nothing. I shall understand, Pyotr Stepanovitch.” The poor boy's voice actually quivered.

“Thank you, Erkel. . . . Aie, you've touched my bad finger.” (Erkel had pressed his hand awkwardly; the bad finger was discreetly bound up in black silk.) “But I tell you positively again that I am going to Petersburg only to sniff round, and perhaps shall only be there for twenty-four hours and then back here again at once. When I come back I shall stay at Gaganov's country place for the sake of appearances. If there is any notion of danger, I should be the first to take the lead and share it. If I stay longer, in Petersburg I'll let you know at once ... in the way we've arranged, and you'll tell them.” The second bell rang.

“Ah, then there's only five, minutes before the train starts. I don't want the group here to break up, you know. I am not afraid; don't be anxious about me. I have plenty of such centres, and it's not much consequence; but there's no harm in haying as many centres as possible. But I am quite at ease about you, though I am leaving you almost alone with those idiots. Don't be uneasy; they won't turn traitor, they won't have the pluck. . . . Ha ha, you going to-day too?” he cried suddenly in a quite different, cheerful voice to a very young man, who came up gaily to greet him. “I didn't know you were going by the express too. Where are you off to ... your mother's?”

The mother of the young man was a very wealthy landowner in a neighbouring province, and the young man was a distant relation of Yulia Mihailovna's and had been staying about a fortnight in our town.

“No, I am going farther, to R–. I've eight hours to live through in the train. Off to Petersburg?” laughed the young man.

“What makes you suppose I must be going to Petersburg?” said Pyotr Stepanovitch, laughing even more openly.

The young man shook his gloved finger at him.

“Well, you've guessed right,” Pyotr Stepanovitch whispered to him mysteriously. “I am going with letters from Yulia Mihailovna and have to call on three or four personages, as you can imagine – bother them all, to speak candidly. It's a beastly job!”

“But why is she in such a panic? Tell me,” the young man whispered too. “She wouldn't see even me yesterday. I don't think she has anything to fear for her husband, quite the contrary; he fell down so creditably at the fire – ready to sacrifice his life, so to speak.”

“Well, there it is,” laughed Pyotr Stepanovitch. “You see, she is afraid that people may have written from here already . . . that is, some gentlemen. . . . The fact is, Stavrogin is at the bottom of it, or rather Prince K. . . . Ech, it's a long story; I'll tell you something about it on the journey if you like – as far as my chivalrous feelings will allow me, at least. . . . This is my relation, Lieutenant Erkel, who lives down here.”

The young man, who had been stealthily glancing at Erkel, touched his hat; Erkel made a bow.

“But I say, Verhovensky, eight hours in the train is an awful ordeal. Berestov, the colonel, an awfully funny fellow, is travelling with me in the first class. He is a neighbour of ours in the country, and his wife is a Garin (neede Garine), and you know he is a very decent fellow. He's got ideas too. He's only been here a couple of days. He's passionately fond of whist; couldn't we get up a game, eh? I've already fixed on a fourth —

Pripuhlov, our merchant from T– with a beard, a millionaire —.I mean it, a real millionaire; you can take my word for it. ... I'll introduce you; he is a very interesting money-bag. We shall have a laugh.”

“I shall be delighted, and I am awfully fond of cards in the train, but I am going second class.”

“Nonsense, that's no matter. Get in with us. I'll tell them directly to move you to the first class. The chief guard would do anything I tell him. What have you got? . . . a bag? a rug?”

“First-rate. Come along!”

Pyotr Stepanovitch took his bag, his rug, and his book, and at once and with alacrity transferred himself to the first class. Erkel helped him. The third bell rang.

“Well, Erkel.” Hurriedly, and with a preoccupied air, Pyotr Stepanovitch held out his hand from the window for the last time. “You see, I am sitting down to cards with them.”

“Why explain, Pyotr Stepanovitch? I understand, I understand it all!”

“Well, au revoir,” Pyotr Stepanovitch turned away suddenly on his name being called by the young man, who wanted to introduce him to his partners. And Erkel saw nothing more of Pyotr Stepanovitch.

He returned home very sad. Not that he was alarmed at Pyotr Stepanovitch's leaving them so suddenly, but ... he had turned away from him so quickly when that young swell had called to him and ... he might have said something different to him, not “Au revoir,” or ... or at least have pressed his hand more warmly. That last was bitterest of all. Something else was beginning to gnaw in his poor little heart, something which he could not understand himself yet, something connected with the evening before.

Last updated on Wed Jan 12 09:26:22 2011 for eBooks@Adelaide.

The Possessed, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Chapter VII. Stepan Trofimovitch's Last Wandering

I am persuaded that Stepan Trofimovitch was terribly frightened as he felt the time fixed for his insane enterprise drawing near. I am convinced that he suffered dreadfully from terror, especially on the night before he started – that awful night. Nastasya mentioned afterwards that he had gone to bed late and fallen asleep. But that proves nothing; men sentenced to death sleep very soundly, they say, even the night before their execution. Though he set off by daylight, when a nervous man is always a little more confident (and the major, Virginsky's relative, used to give up believing in God every morning when the night was over), yet I am convinced he could never, without horror, have imagined himself alone on the high road in such a position. No doubt a certain desperation in his feelings softened at first the terrible sensation of sudden solitude in which he at once found himself as soon as he had left Nastasya, and the corner in which he had been warm and snug for twenty years. But it made no difference; even with the clearest recognition of all the horrors awaiting him he would have gone out to the high road and walked along it! There was something proud in the undertaking which allured him in spite of everything. Oh, he might have accepted Varvara Petrovna's luxurious provision and have remained living on her charity, “ comme unhumble dependent.” But he had not accepted her charity and was not remaining! And here he was leaving her of himself, and holding aloft the “standard of a great idea, and going to die for it on the open road.” That is how he must have been feeling; that's how his action must have appeared to him.

Another question presented itself to me more than once. Why did he run away, that is, literally run away on foot, rather than simply drive away? I put it down at first to the impracticability of fifty years and the fantastic bent of his mind under the influence of strong emotion. I imagined that the thought of posting tickets and horses (even if they had bells) would have seemed too simple and prosaic to him; a pilgrimage, on the other hand, even under an umbrella, was ever so much more picturesque and in character with love and resentment. But now that everything is over, I am inclined to think that it all came about in a much simpler way. To begin with, he was afraid to hire horses because Varvara Petrovna might have heard of it and prevented him from going by force; which she certainly would have done, and he certainly would have given in, and then farewell to the great idea for ever. Besides, to take tickets for anywhere he must have known at least where he was going. But to think about that was the greatest agony to him at that moment; he was utterly unable to fix upon a place. For if he had to fix on any particular town his enterprise would at once have seemed in his own eyes absurd and impossible; he felt that very strongly. What should he do in that particular town rather than in any other? Look out for ce marchand?But what marchand?At that point his second and most terrible question cropped up. In reality there was nothing he dreaded more than ce marchand,whom he had rushed off to seek so recklessly, though, of course, he was terribly afraid of finding him. No, better simply the high road, better simply to set off for it, and walk along it and to think of nothing so long as he could put off thinking. The high road is something very very long, of which one cannot see the end – like human life, like human dreams. There is an idea in the open road, but what sort of idea is there in travelling with posting tickets? Posting tickets mean an end to ideas. Vive la grande routeand then as God wills.

After the sudden and unexpected interview with Liza which I have described, he rushed on, more lost in forgetfulness than ever. The high road passed half a mile from Skvoreshniki and, strange to say, he was not at first aware that he was on it. Logical reasoning or even distinct consciousness was unbearable to him at this moment. A fine rain kept drizzling, ceasing, and drizzling again; but he did not even notice the rain. He did not even notice either how he threw his bag over his shoulder, nor how much more comfortably he walked with it so. He must have walked like that for nearly a mile or so when he suddenly stood still and looked round. The old road, black, marked with wheel-ruts and planted with willows on each side, ran before him like an endless thread; on the right hand were bare plains from which the harvest had long ago been carried; on the left there were bushes and in the distance beyond them a copse.

And far, far away a scarcely perceptible line of the railway, running aslant, and on it the smoke of a train, but no sound was heard. Stepan Trofimovitch felt a little timid, but only for a moment. He heaved a vague sigh, put down his bag beside a willow, and sat down to rest. As he moved to sit down he was conscious of being chilly and wrapped himself in his rug; noticing at the same time that it was raining, he put up his umbrella. He sat like that for some time, moving his lips from time to time and firmly grasping the umbrella handle. Images of all sorts passed in feverish procession before him, rapidly succeeding one another in his mind.

“Lise, Lise,” he thought, “and with her ce Maurice. . . .Strange people. . . . But what was the strange fire, and what were they talking about, and who were murdered? I fancy Nastasya has not found out yet and is still waiting for me with my coffee . . . cards? Did I really lose men at cards? H'm! Among us in Russia in the times of serfdom, so called. . . . My God, yes – Fedka!”

He started all over with terror and looked about him. “What if that Fedka is in hiding somewhere behind the bushes? They say he has a regular band of robbers here on the high road. Oh, mercy, I ... I'll tell him the whole truth then, that I was to blame . . . and that I've been miserable about him for ten years.More miserable than he was as a soldier, and . . . I'll give him my purse. H'm! J'ai en tout quarante roubles; il prendra les roubles et il me tuera tout de meme.”

In his panic he for some reason shut up the umbrella and laid it down beside him. A cart came into sight on the high road in the distance coming from the town.

“ Grace a Dieu,that's a cart and it's coming at a walking pace; that can't be dangerous. The wretched little horses here ... I always said that breed ... It was Pyotr Ilyitch though, he talked at the club about horse-breeding and I trumped him, et puis . . .but what's that behind? . . . I believe there's a woman in the cart. A peasant and a woman, cela commenced etre rassurant.The woman behind and the man in front – c'est tres rassurant.There's a cow behind the cart tied by the horns, c'est rassurant au plus haut degre.”

The cart reached him; it was a fairly solid peasant cart. The woman was sitting on a tightly stuffed sack and the man on the front of the cart with his legs hanging over towards Stepan Trofimovitch. A red cow was, in fact, shambling behind, tied by the horns to the cart. The man and the woman gazed open-eyed at Stepan Trofimovitch, and Stepan Trofimovitch gazed back at them with equal wonder, but after he had let them pass twenty paces, he got up hurriedly all of a sudden and walked after them. In the proximity of the cart it was natural that he should feel safer, but when he had overtaken it he became oblivious of everything again and sank back into his disconnected thoughts and fancies. He stepped along with no suspicion, of course, that for the two peasants he was at that instant the most mysterious and interesting object that one could meet on the high road.

“What sort may you be, pray, if it's not uncivil to ask?” the woman could not resist asking at last when Stepan Trofimovitch glanced absent-mindedly at her. She was a woman of about seven and twenty, sturdily built, with black eyebrows, rosy cheeks, and a friendly smile on her red lips, between which gleamed white even teeth.

“You . . . you are addressing me?” muttered Stepan Trofimovitch with mournful wonder.

“A merchant, for sure,” the peasant observed confidently. He was a well-grown man of forty with a broad and intelligent face, framed in a reddish beard.

“No, I am not exactly a merchant, I ... I ... moi c'est autre chose.” Stepan Trofimovitch parried the question somehow, and to be on the safe side he dropped back a little from the cart, so that he was walking on a level with the cow.

“Must be a gentleman,” the man decided, hearing words not Russian, and he gave a tug at the horse.

“That's what set us wondering. You are out for a walk seemingly?” the woman asked inquisitively again.

“You . . . you ask me?”

“Foreigners come from other parts sometimes by the train; your boots don't seem to be from hereabouts. . . .”

“They are army boots,” the man put in complacently and significantly.

“No, I am not precisely in the army, I ...”

“What an inquisitive woman!” Stepan Trofimovitch mused with vexation. “And how they stare at me . . . mais enfin.In fact, it's strange that I feel, as it were, conscience-stricken before them, and yet I've done them no harm.”

The woman was whispering to the man.

“If it's no offence, we'd give you a lift if so be it's agreeable.”

Stepan Trofimovitch suddenly roused himself.

“Yes, yes, my friends, I accept it with pleasure, for I'm very tired; but how am I to get in?”

“How wonderful it is,” he thought to himself, “that I've been walking so long beside that cow and it never entered my head to ask them for a lift. This 'real life' has something very original about it.”

But the peasant had not, however, pulled up the horse.

“But where are you bound for?” he asked with some mistrustfulness.

Stepan Trofimovitch did not understand him at once.

“To Hatovo, I suppose?”

“Hatov? No, not to Hatov's exactly? . . . And I don't know him though I've heard of him.”

“The village of Hatovo, the village, seven miles from here.”

“A village? C'est charmant,to be sure I've heard of it. . . .”

Stepan Trofimovitch was still walking, they had not yet taken him into the cart. A guess that was a stroke of genius flashed through his mind.

“You think perhaps that I am . . . I've got a passport and I am a professor, that is, if you like, a teacher . . . but a head teacher. I am a head teacher. Oui, c'est comme ca qu'on pent traduire.I should be very glad of a lift and I'll buy you . . . I'll buy you a quart of vodka for it.”

“It'll be half a rouble, sir; it's a bad road.”

“Or it wouldn't be fair to ourselves,” put in the woman.

“Half a rouble? Very good then, half a rouble. C'est encore mieux; fai en tout quarante roubles mais . . .”

The peasant stopped the horse and by their united efforts Stepan Trofimovitch was dragged into the cart, and seated on the sack by the woman. He was still pursued by the same whirl of ideas. Sometimes he was aware himself that he was terribly absent-minded, and that he was not thinking of what he ought to be thinking of and wondered at it. This consciousness of abnormal weakness of mind became at moments very painful and even humiliating to him.

“How . . . how is this you've got a cow behind?” he suddenly asked the woman.

“What do you mean, sir, as though you'd never seen one,” laughed the woman.

“We bought it in the town,” the peasant put in. “Our cattle died last spring . . . the plague. All the beasts have died round us, all of them. There aren't half of them left, it's heartbreaking.”

And again he lashed the horse, which had got stuck in a rut.

“Yes, that does happen among you in Russia ... in general we Russians . . . Well, yes, it happens,” Stepan Trofimovitch broke off.

“If you are a teacher, what are you going to Hatovo for? Maybe you are going on farther.”

“I ... I'm not going farther precisely. . . . C'est-d-dire,I'm going to a merchant's.”

“To Spasov, I suppose?”

“Yes, yes, to Spasov. But that's no matter.”

“If you are going to Spasov and on foot, it will take you a week in your boots,” laughed the woman.

“I dare say, I dare say, no matter, mes amis,no matter.” Stepan Trofimovitch cut her short impatiently.

“Awfully inquisitive people; but the woman speaks better than he does, and I notice that since February 19,* their language has altered a little, and . . . and what business is it of mine whether I'm going to Spasov or not? Besides, I'll pay them, so why do they pester me.”

“If you are going to Spasov, you must take the steamer,” the peasant persisted.

.” That's true indeed,” the woman put in with animation, “for if you drive along the bank it's twenty-five miles out of the way.”

“Thirty-five.”

“You'll just catch the steamer at Ustyevo at two o'clock tomorrow,” the woman decided finally. But Stepan Trofimovitch was obstinately silent. His questioners, too, sank into silence. The peasant tugged at his horse at rare intervals; the peasant woman exchanged brief remarks with him. Stepan Trofimovitch fell into a doze. He was tremendously surprised when the woman, laughing, gave him a poke and he found himself in a rather large village at the door of a cottage with three windows.

“You've had a nap, sir?”

“What is it? Where am I? Ah, yes! Well . . . never mind,” sighed Stepan Trofimovitch, and he got out of the cart.

He looked about him mournfully; the village scene seemed strange to him and somehow terribly remote.

*February 19, 1861, the day of the Emancipation of the Serfs, is meant.– Translator's note.

“And the half-rouble, I was forgetting it!” he said to the peasant, turning to him with an excessively hurried gesture; he was evidently by now afraid to part from them.

“We'll settle indoors, walk in,” the peasant invited him.

“It's comfortable inside,” the woman said reassuringly.

Stepan Trofimovitch mounted the shaky steps. “How can it be?” he murmured in profound and apprehensive perplexity. He went into the cottage, however. “ Elle Pa voulu” he felt a stab at his heart and again he became oblivious of everything, even of the fact that he had gone into the cottage.

It was a light and fairly clean peasant's cottage, with three windows and two rooms; not exactly an inn, but a cottage at which people who knew the place were accustomed to stop “on their way through the village. Stepan Trofimovitch, quite unembarrassed, went to the foremost corner; forgot to greet anyone, sat down and sank into thought. Meanwhile a sensation of warmth, extremely agreeable after three hours of travelling in the damp, was suddenly diffused throughout his person. Even the slight shivers that spasmodically ran down his spine – such as always occur in particularly nervous people when they are feverish and have suddenly come into a Warm room from the cold – became all at once strangely agreeable. He raised his head and the delicious fragrance of the hot pancakes with which the woman of the house was busy at the stove tickled his nostrils. With a childlike smile he leaned towards the woman and suddenly said:

“What's that? Are they pancakes? Mais . . . c'est char-mant.”

“Would you like some, sir?” the woman politely offered him at once.

“I should like some, I certainly should, and . . . may I ask you for some tea too,” said Stepan Trofimovitch, reviving.

“Get the samovar? With the greatest pleasure.”

On a large plate with a big blue pattern on it were served the pancakes – regular peasant pancakes, thin, made half of wheat, covered with fresh hot butter, most delicious pancakes. Stepan Trofimovitch tasted them with relish.

“How rich they are and how good! And if one could only have un doigt d'eau de vie.”

“It's a drop of vodka you would like, sir, isn't it?”

“Just so, just so, a little, un tout petitnew,”