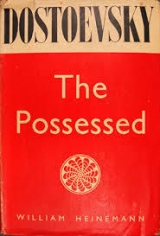

Текст книги "The Possessed"

Автор книги: Федор Достоевский

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 42 (всего у книги 49 страниц)

The Possessed, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Chapter V. A Wanderer

THE CATASTROPHE WITH Liza and the death of Marya Timofyevna made an overwhelming impression on Shatov. I have already mentioned that that morning I met him in passing; he seemed to me not himself. He told me among other things that on the evening before at nine o'clock (that is, three hours before the fire had broken out) he had been at Marya Timofyevna's. He went in the morning to look at the corpses, but as far as I know gave no evidence of any sort that morning. Meanwhile, towards the end of the day there was a perfect tempest in his soul, and . . . I think I can say with certainty that there was a moment at dusk when he wanted to get up, go out and tell everything. What that everythingwas, no one but he could say. Of course he would have achieved nothing, and would have simply betrayed himself. He had no proofs whatever with which to convict the perpetrators of the crime, and, indeed, he had nothing but vague conjectures to go upon, though to him they amounted to complete certainty. But he was ready to ruin himself if he could only “crush the scoundrels”– his own words. Pyotr Stepanovitch had guessed fairly correctly at this impulse in him, and he knew himself that he was risking a great deal in putting off the execution of his new awful project till next day. On his side there was, as usual, great self-confidence and contempt for all these “wretched creatures” and for Shatov in particular. He had for years despised Shatov for his “whining idiocy,” as he had expressed it in former days abroad, and he was absolutely confident that he could deal with such a guileless creature, that is, keep an eye on him all that day, and put a check on him at the first sign of danger. Yet what saved “the scoundrels” for a short time was something quite unexpected which they had not foreseen. . . .

Towards eight o'clock in the evening (at the very time when the quintet was meeting at Erkel's, and waiting in indignation and excitement for Pyotr Stepanovitch) Shatov was lying in the dark on his bed with a headache and a slight chill; he was tortured by uncertainty, he was angry, he kept making up his mind, and could not make it up finally, and felt, with a curse, that it would all lead to nothing. Gradually he sank into a brief doze and had something like a nightmare. He dreamt that he was lying on his bed, tied up with cords and unable to stir, and meantime he heard a terrible banging that echoed all over the house, a banging on the fence, at the gate, at his door, in Kirillov's lodge, so that the whole house was shaking, and a far-away familiar voice that wrung his heart was calling to him piteously. He suddenly woke and sat up in bed. To his surprise the banging at the gate went on, though not nearly so violent as it had seemed in his dream. The knocks were repeated and persistent, and the strange voice “that wrung his heart” could still be heard below at the gate, though not piteously but angrily and impatiently, alternating with another voice, more restrained and ordinary. He jumped up, opened the casement pane and put his head out.

“Who's there?” he called, literally numb with terror.

“If you are Shatov,” the answer came harshly and resolutely from below, “be so good as to tell me straight out and honestly whether you agree to let me in or not?”

It was true: he recognised the voice!

“Marie! . . . Is it you?”

“Yes, yes, Marya Shatov, and I assure you I can't keep the driver a minute longer.”

“This minute . . . I'll get a candle,” Shatov cried faintly. Then he rushed to look for the matches. The matches, as always happens at such moments, could not be found. He dropped the candlestick and the candle on the floor and as soon as he heard the impatient voice from below again, he abandoned the search and dashed down the steep stairs to open the gate.

“Be so good as to hold the bag while I settle with this blockhead,” was how Madame Marya Shatov greeted him below, and she thrust into his hands a rather light cheap canvas handbag studded with brass nails, of Dresden manufacture. She attacked the driver with exasperation.

“Allow me to tell you, you are asking too much. If you've been driving me for an extra hour through these filthy streets, that's your fault, because it seems you didn't know where to find this stupid street and imbecile house. Take your thirty kopecks and make up your mind that you'll get nothing more.”

“Ech, lady, you told me yourself Voznesensky Street and this is Bogoyavlensky; Voznesensky is ever so far away. You've simply put the horse into a steam.”

“Voznesensky, Bogoyavlensky – you ought to know all those stupid names better than I do, as you are an inhabitant; besides, you are unfair, I told you first of all Filipov's house and you declared you knew it. In any case you can have me up to-morrow in the local court, but now I beg you to let me alone.”

“Here, here's another five kopecks.” With eager haste Shatov pulled a five-kopeck piece out of his pocket and gave it to the driver.

“Do me a favour, I beg you, don't dare to do that!” Madame Shatov flared up, but the driver drove off and Shatov, taking her hand, drew her through the gate.

“Make haste, Marie, make haste . . . that's no matter, and . . . you are wet through. Take care, we go up here – how sorry I am there's no light – the stairs are steep, hold tight, hold tight! Well, this is my room. Excuse my having no light.

. . One minute!”

He picked up the candlestick but it was a long time before the matches were found. Madame Shatov stood waiting in the middle of the room, silent and motionless.

“Thank God, here they are at last!” he cried joyfully, lighting up the room. Marya Shatov took a cursory survey of his abode.

“They told me you lived in a poor way, but I didn't expect it to be as bad as this,” she pronounced with an air of disgust, and she moved towards the bed.

“Oh, I am tired!” she sat down on the hard bed, with an exhausted air. “Please put down the bag and sit down on the chair yourself. Just as you like though; you are in the way standing there. I have come to you for a time, till I can get work, because I know nothing of this place and I have no money. But if I shall be in your way I beg you again, be so good as to tell me so at once, as you are bound to do if you are an honest man. I could sell something to-morrow and pay for a room at an hotel, but you must take me to the hotel yourself. . . . Oh, but I am tired!”

Shatov was all of a tremor.

“You mustn't, Marie, you mustn't go to an hotel? An hotel! What for? What for?”

He clasped his hands imploringly.. . .

“Well, if I can get on without the hotel ... I must, any way ,explain the position. Remember, Shatov, that we lived in Geneva as man and wife for a fortnight and a few days; it's three years since we parted, without any particular quarrel though. But don't imagine that I've come back to renew any of the foolishness of the past. I've come back to look for work, and that I've come straight to this town is just because it's all the same to me. I've not come to say I am sorry for anything; please don't imagine anything so stupid as that.”

“Oh, Marie! This is unnecessary, quite unnecessary,” Shatov muttered vaguely.

“If so, if you are so far developed as to be able to understand that, I may allow myself to add, that if I've come straight to you now and am in your lodging, it's partly because I always thought you were far from being a scoundrel and were perhaps much better than other . . . blackguards!”

Her eyes flashed. She must have had to bear a great deal at the hands of some “blackguards.”

“And please believe me, I wasn't laughing at you just now when I told you you were good. I spoke plainly, without fine phrases and I can't endure them. But that's all nonsense. I always hoped you would have sense enough not to pester me. . . . Enough, I am tired.”

And she bent on him a long, harassed and weary gaze. Shatov stood facing her at the other end of the room, which was five paces away, and listened to her timidly with a look of new life and unwonted radiance on his face. This strong, rugged man, all bristles on the surface, was suddenly all softness and shining gladness. There was a thrill of extraordinary and unexpected feeling in his soul. Three years of separation, three years of the broken marriage had effaced nothing from his heart. And perhaps every day during those three years he had dreamed of her, of that beloved being who had once said to him, “I love you.” Knowing Shatov I can say with certainty that he could never have allowed himself even to dream that a woman might say to him, “I love you.” He was savagely modest and chaste, he looked on himself as a perfect monster, detested his own face as well as his character, compared himself to some freak only fit to be exhibited at fairs. Consequently he valued honesty above everything and was fanatically devoted to his convictions; he was gloomy, proud, easily moved to wrath, and sparing of words. But here was the one being who had loved him for a fortnight (that he had never doubted, never!), a being he had always considered immeasurably above him in spite of his perfectly sober understanding of her errors; ,a being to whom he could forgive everything, everything(of that there could be no question; indeed it was quite the other way, his idea was that he was entirely to blame); this woman, this Marya Shatov, was in his house, in his presence again ... it was almost inconceivable! He was so overcome, there was so much that was terrible and at the same time so much happiness in this event that he could not, perhaps would not – perhaps was afraid to – realise the position. It was a dream. But when she looked at him with that harassed gaze he suddenly understood that this woman he loved so dearly was suffering, perhaps had been wronged. His heart went cold. He looked at her features with anguish: the first bloom of youth had long faded from this exhausted face. It's true that she was still good-looking – in his eyes a beauty, as she had always been. In reality she was a woman of twenty-five, rather strongly built, above the medium height (taller than Shatov), with abundant dark brown hair, a pale oval face, and large dark eyes now glittering with feverish brilliance. But the light-hearted, naive and good-natured energy he had known so well in the past was replaced now by a sullen irritability and disillusionment, a sort of cynicism which was not yet habitual to her herself, and which weighed upon her. But the chief thing was that she was ill, that he could see clearly. In spite of the awe in which he stood of her he suddenly went up to her and took her by both hands.

“Marie . . . you know . . . you are very tired, perhaps, for God's sake, don't be angry. ... If you'd consent to have some tea, for instance, eh? Tea picks one up so, doesn't it? If you'd consent!”

“Why talk about consenting! Of course I consent, what a baby you are still. Get me some if you can. How cramped you are here. How cold it is!”

“Oh, I'll get some logs for the fire directly, some logs . . . I've got logs.” Shatov was all astir. “Logs . . . that is . . . but I'll get tea directly,” he waved his hand as though with desperate determination and snatched up his cap.

“Where are you going? So you've no tea in the house?”

“There shall be, there shall be, there shall be, there shall be everything directly. ... I ...” he took his revolver from the shelf, “I'll sell this revolver directly . . . or pawn it. . . .”

' 'What foolishness and what a time that will take! Take my money if you've nothing, there's eighty kopecks here, I think; that's all I have. This is like a madhouse.”

“I don't want your money, I don't want it I'll be here directly, in one instant. I can manage without the revolver. . . .”

And he rushed straight to Kirillov's. This was probably two hours before the visit of Pyotr Stepanovitch and Liputin to Kirillov. Though Shatov and Kirillov lived in the same yard they hardly ever saw each other, and when they met they did not nod or speak: they had been too long “lying side by side” in America....

“Kirillov, you always have tea; have you got tea and a

samovar?”

Kirillov, who was walking up and down the room, as he was in the habit of doing all night, stopped and looked intently at his hurried visitor, though without much surprise.

“I've got tea and sugar and a samovar. But there's no need of the samovar, the tea is hot. Sit down and simply drink it.”

“Kirillov, we lay side by side in America. . . . My wife has come to me ... I ... give me the tea. ... I shall want the samovar.”

“If your wife is here you want the samovar. But take it later. I've two. And now take the teapot from the table. It's hot, boiling hot. Take everything, take the sugar, all of it. Bread . . . there's plenty of bread; all of it. There's some veal. I've a rouble.”

“Give it me, friend, I'll pay it back to-morrow! Ach, Kirillov!”

“Is it the same wife who was in Switzerland? That's a good thing. And your running in like this, that's a good thing too.”

“Kirillov!” cried Shatov, taking the teapot under his arm and carrying the bread and sugar in both hands. “Kirillov, if ... if you could get rid of your dreadful fancies and give up your atheistic ravings ... oh, what a man you'd be, Kirillov!”

“One can see you love your wife after Switzerland. It's a good thing you do – after Switzerland. When you want tea, come again. You can come all night, I don't sleep at all. There'll be a samovar. Take the rouble, here it is. Go to your wife, I'll stay here and think about you and your wife.”

Marya Shatov was unmistakably pleased at her husband's haste and fell upon the tea almost greedily, but there was no need to run for the samovar; she drank only half a cup and swallowed a tiny piece of bread. The veal she refused with disgust and irritation.

“You are ill, Marie, all this is a sign of illness,” Shatov remarked timidly as he waited upon her.

“Of course I'm ill, please sit down. Where did you get the tea if you haven't any?”

Shatov told her about Kirillov briefly. She had heard something of him.

“I know he is mad; say no more, please; 'there are plenty of fools. So you've been in America? I heard, you wrote.”

“Yes, I ... I wrote to you in Paris.”

“Enough, please talk of something else. Are you a Slavophil in your convictions?”

“I . . .1 am not exactly. . . . Since I cannot be a Russian, I became a Slavophil.” He smiled a wry smile with the effort of one who feels he has made a strained and inappropriate jest.

“Why, aren't you a Russian?”

“No, I'm not.”

“Well, that's all foolishness. Do sit down, I entreat you. Why are you all over the place? Do you think I am lightheaded? Perhaps I shall be. You say there are only you two in the house.”

“Yes. . . . Downstairs . . .”

“And both such clever people. What is there downstairs? You said downstairs?”

“No, nothing.”

“Why nothing? I want to know.”

“I only meant to say that now we are only two in the yard, but that the Lebyadkins used to live downstairs. ...”

“That woman who was murdered last night?” she started suddenly. “I heard of it. I heard of it as soon as I arrived. There was a fire here, wasn't there?”

“Yes, Marie, yes, and perhaps I am doing a scoundrelly thing this moment in forgiving the scoundrels. ...” He stood up suddenly and paced about the room, raising his arms as though in a frenzy.

But Marie had not quite understood him. She heard his answers inattentively; she asked questions but did not listen.

“Fine things are being done among you! Oh, how contemptible it all is! What scoundrels men all are! But do sit down, I beg you, oh, how you exasperate me!” and she let her head sink on the pillow, exhausted.

“Marie, I won't. . . . Perhaps you'll lie down, Marie?” She made no answer and closed her eyes helplessly. Her pale face looked death-like. She fell asleep almost instantly. Shatov looked round, snuffed the candle, looked uneasily at her face once ,more, pressed his hands tight in front of him and walked on tiptoe out of the room into the passage. At the top of the stairs he stood in the corner with his face to the wall and remained so for ten minutes without sound or movement. He would have stood there longer, but he suddenly caught the sound of soft cautious steps below. Some one was coming up the stairs. Shatov remembered he had forgotten to fasten the gate.

“Who's there?” he asked in a whisper. The unknown visitor went on slowly mounting the stairs without answering. When he reached the top he stood still; it was impossible to see his face in the dark; suddenly Shatov heard the cautious question:

“Ivan Shatov?”

Shatov said who he was, but at once held out his hand to check his advance. The latter took his hand, and Shatov shuddered as though he had touched some terrible reptile.

“Stand here,” he whispered quickly. “Don't go in, I can't receive you just now. My wife has come back. I'll fetch the candle.”

When he returned with the candle he found a young officer standing there; he did not know his name but he had seen him before.

“Erkel,” said the lad, introducing himself. “You've seen me at Virginsky's.”

“I remember; you sat writing. Listen,” said Shatov in sudden excitement, going up to him frantically, but still talking in a whisper. “You gave me a sign just now when you took my hand. But you know I can treat all these signals with contempt! I don't acknowledge them. . . . I don't want them. .. . I can throw you downstairs this minute, do you know that?”

“No, I know nothing about that and I don't know what you are in such a rage about,” the visitor answered without malice and almost ingenuously. “I have only to give you a message, and that's what I've come for, being particularly anxious not to lose time. You have a printing press which does not belong to you, and of which you are bound to give an account, as you know yourself. I have received instructions to request you to give it up to-morrow at seven o'clock in the evening to Liputin. I have been instructed to tell you also that nothing more will be asked of you.”

“Nothing?”

“Absolutely nothing. Your request is granted, and you are struck off our list. I was instructed to tell you that positively.”

“Who instructed you to tell me?”

“Those who told me the sign.”

“Have you come from abroad?”

“I ... I think that's no matter to you.”

“Oh, hang it! Why didn't you come before if you were told to?”

“I followed certain instructions and was not alone.”

“I understand, I understand that you were not alone. Eh . . . hang it! But why didn't Liputin come himself?”

“So I shall come for you to-morrow at exactly six o'clock in the evening, and we'll go there on foot. There will be no one there but us three.”

“Will Verhovensky be there?”

“No, he won't. Verhovensky is leaving the town at eleven o'clock to-morrow morning.”

“Just what I thought!” Shatov whispered furiously, and he struck his fist on his hip. “He's run off, the sneak!”

He sank into agitated reflection. Erkel looked intently at him and waited in silence.

“But how will you take it? You can't simply pick it up in your hands and carry it.”

“There will be no need to. You'll simply point out the place and we'll just make sure that it really is buried there. We only know whereabouts the place is, we don't know the place itself. And have you pointed the place out to anyone else yet?” Shatov looked at him.

“You, you, a chit of a boy like you, a silly boy like you, you too have got caught in that net like a sheep? Yes, that's just the young blood they want! Well, go along. E-ech! that scoundrel's taken you all in and run away.”

Erkel looked at him serenely and calmly but did not seem to understand.

“Verhovensky, Verhovensky has run away!” Shatov growled fiercely.

“But he is still here, he is not gone away. He is not going till to-morrow,” Erkel observed softly and persuasively. “I particularly begged him to be present as a witness; my instructions all referred to him (he explained frankly like a young and inexperienced boy). But I regret to say he did not agree on the ground of his departure, and he really is in a hurry.”

Shatov glanced compassionately at the simple youth again, but suddenly gave a gesture of despair as though he thought “they are not worth pitying.”

“All right, I'll come,” he cut him short. “And now get away, be off.”

“So I'll come for you at six o'clock punctually.” Erkel made a courteous bow and walked deliberately downstairs.

“Little fool!” Shatov could not help shouting after him from the top.

“What is it?” responded the lad from the bottom.

“Nothing, you can go.”

“I thought you said something.”

II

Erkel was a “little fool” who was only lacking in the higher form of reason, the ruling power of the intellect; but of the lesser, the subordinate reasoning faculties, he had plenty – even to the point of cunning. Fanatically, childishly devoted to “the cause” or rather in reality to Pyotr Verhovensky, he acted on the instructions given to him when at the meeting of the quintet they had agreed and had distributed the various duties for the next day. When Pyotr Stepanovitch gave him the job of messenger, he succeeded in talking to him aside for ten minutes.

A craving for active service was characteristic of this shallow, unreflecting nature, which was for ever yearning to follow the lead of another man's will, of course for the good of “the common” or “the great” cause. Not that that made any difference, for little fanatics like Erkel can never imagine serving a cause except by identifying it with the person who, to their minds, is the expression of it. The sensitive, affectionate and kind-hearted Erkel was perhaps the most callous of Shatov's would-be murderers, and, though he had no personal spite against him, he would have been present at his murder without-the quiver of an eyelid. He had been instructed; for instance, to have a good look at Shatov's surroundings while carrying out his commission, and when Shatov, receiving him at the top of the stairs, blurted out to him, probably unaware in the heat of the moment, that his wife had come back to him – Erkel had the instinctive cunning to avoid displaying the slightest curiosity, though the idea flashed through his mind that the fact of his wife's return was of great importance for the success of their undertaking.

And so it was in reality; it was only that fact that saved the “scoundrels” from Shatov's carrying out his intention, and at the same time helped them “to get rid of him.” To begin with, it agitated Shatov, threw him out of his regular routine, and deprived him of his usual clear-sightedness and caution. Any idea of his own danger would be the last thing to enter his head at this moment when he was absorbed with such different considerations. On the contrary, he eagerly believed that Pyotr Verhovensky was running away the next day: it fell in exactly with his suspicions! Returning to the room he sat down again in a corner, leaned his elbows on his knees and hid his face in his hands. Bitter thoughts tormented him. . . .

Then he would raise his head again and go on tiptoe to look at her. “Good God! she will be in a fever by to-morrow morning; perhaps it's begun already! She must have caught cold. She is not accustomed to this awful climate, and then a third-class carriage, the storm, the rain, and she has such a thin little pelisse, no wrap at all. . . . And to leave her like this, to abandon her in her helplessness! Her bag, too, her bag – what a tiny, light thing, all crumpled up, scarcely weighs ten pounds! Poor thing, how worn out she is, how much she's been through! She is proud, that's why she won't complain. But she is irritable, very irritable. It's illness; an angel will grow irritable in illness. What a dry forehead, it must be hot – how dark she is under the eyes, and . . . and yet how beautiful the oval of her face is and her rich hair, how ...”

And he made haste to turn away his eyes, to walk away as though he were frightened at the very idea of seeing in her anything but an unhappy, exhausted fellow-creature who needed help—“ how could he think of hopes,oh, how mean, how base is man!” And he would go back to his corner, sit down, hide his face in his hands and again sink into dreams and reminiscences . . . and again he was haunted by hopes.

“Oh, I am tired, I am tired,” he remembered her exclamations, her weak broken voice. “Good God! Abandon her now, and she has only eighty kopecks; she held out her purse, a tiny old thing! She's come to look for a job. What does she know about jobs? What do they know about Russia? Why, they are like naughty children, they've nothing but their own fancies made up by themselves, and she is angry, poor thing, that Russia is not like their foreign dreams! The luckless, innocent creatures! . . . It's really cold here, though.”

He remembered that she had complained, that he had promised to heat the stove. “There are logs here, I can fetch them if only I don't wake her. But I can do it without waking her. But what shall I do about the veal? When she gets up perhaps she will be hungry. . . . Well, that will do later: Kirillov doesn't go to bed all night. What could I cover her with, she is sleeping so soundly, but she must be cold, ah, she must be cold!” And once more he went to look at her; her dress had worked up a little and her right leg was half uncovered to the knee. He suddenly turned away almost in dismay, took off his warm overcoat, and, remaining in his wretched old jacket, covered it up, trying not to look at it.

A great deal of time was spent in righting the fire, stepping about on tiptoe, looking at the sleeping woman, dreaming in the corner, then looking at her again. Two or three hours had passed. During that time Verhovensky and Liputin had been at Kirillov's. At last he, too, began to doze in the corner. He heard her groan; she waked up and called him; he jumped up like a criminal.

“Marie, I was dropping asleep.' . . . Ah, what a wretch I am, Marie!”

She sat up, looking about her with wonder, seeming not to recognise where she was, and suddenly leapt up in indignation and anger.

“I've taken your bed, I fell asleep so tired I didn't know what I was doing; how dared you not wake me? How could you dare imagine I meant to be a burden to you?”

“How could I wake you, Marie?”

“You could, you ought to have! You've no other bed here, and I've taken yours. You had no business to put me into a false position. Or do you suppose that I've come to take advantage of your charity? Kindly get into your bed at once and I'll lie down in the corner on some chairs.”

“Marie, there aren't chairs enough, and there's nothing to put on them.”

“Then simply oil the floor. Or you'll have to lie on the floor yourself. I want to lie on the floor at once, at once!”

She stood up, tried to take a step, but suddenly a violent spasm of pain deprived her of all power and all determination, and with a loud groan she fell back on the bed. Shatov ran up, but Marie, hiding her face in the pillow, seized his hand and gripped and squeezed it with all her might. This lasted a minute.

“Marie darling, there's a doctor Frenzel living here, a friend of mine. ... I could run for him.”

“Nonsense!”

“What do you mean by nonsense? Tell me, Marie, what is it hurting you? For we might try fomentations ... on the stomach for instance. ... I can do that without a doctor. . . . Or else mustard poultices.”

“What's this,” she asked strangely, raising her head and looking at him in dismay.

“What's what, Marie?” said Shatov, not understanding. “What are you asking about? Good heavens! I am quite bewildered, excuse my not understanding.”

“Ach, let me alone; it's not your business to understand. And it would be too absurd . . .” she said with a bitter smile. “Talk to me about something. Walk about the room and talk. Don't stand over me and don't look at me, I particularly ask you that for the five-hundredth time!”

Shatov began walking up and down the room, looking at the floor, and doing his utmost not to glance at her.

“There's – don't be angry, Marie, I entreat you – there's some veal here, and there's tea not far off. . . . You had so little before.”

She made an angry gesture of disgust. Shatov bit his tongue in despair.

“Listen, I intend to open a bookbinding business here, on rational co-operative principles. Since you live here what do you think of it, would it be successful?”

“Ech, Marie, people don't read books here, and there are none here at all. And are they likely to begin binding them!”

“Who are they?”

“The local readers and inhabitants generally, Marie.”

“Well, then, speak more clearly. Theyindeed, and one doesn't know who they are. You don't know grammar!”

“It's in the spirit of the language,” Shatov muttered.

“Oh, get along with your spirit, you bore me. Why shouldn't the local inhabitant or reader have his books bound?”

“Because reading books and having them bound are two different stages of development, and there's a vast gulf between them. To begin with, a man gradually gets used to reading, in the course of ages of course, but takes no care of his books and throws them about, not thinking them worth attention. But binding implies respect for books, and implies that not only he has grown fond of reading, but that he looks upon it as something of value. That period has not been reached anywhere in Russia yet. In Europe books have been bound for a long while.”

“Though that's pedantic, anyway, it's not stupid, and reminds me of the time three years ago; you used to be rather clever sometimes three years ago.”

She said this as disdainfully as her other capricious remarks.

“Marie, Marie,” said Shatov, turning to her, much moved, “oh, Marie! If you only knew how much has happened in those three years! I heard afterwards that you despised me for changing my convictions. But what are the men I've broken with? The enemies of all true life, out-of-date Liberals who are afraid of their own independence, the flunkeys of thought, the enemies of individuality and freedom, the decrepit advocates of deadness and rottenness! All they have to offer is senility, a glorious mediocrity of the most bourgeois kind, contemptible shallowness, a jealous equality, equality without individual dignity, equality as it's understood by flunkeys or by the French in '93. And the worst of it is there are swarms of scoundrels among them, swarms of scoundrels!”