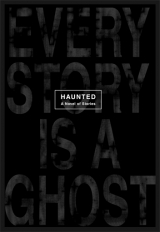

Текст книги "Haunted"

Автор книги: Charles Michael «Chuck» Palahniuk

Жанр:

Повесть

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Tracee always worried about being a Top-A priority target, about getting machine-gunned on her way to the gym. But most of the squads were in the countryside or the mountains, places where backward baby-having people might hide.

The stupidest stupid people could completely sidetrack your spiritual evolution. It just wasn't fair.

Everybody else, millions of souls, they were already at the party. On the Venus video, you could catch the faces of famous people who'd suffered enough on Earth and didn't have to come back for another life. You'd see Grace Kelly and Jim Morrison. Jackie Kennedy and John Lennon. Kurt Cobain. Those were ones Eve could recognize. They were all at the party, looking young and happy, forever.

Among the dead celebrities roamed animals extinct on Earth: passenger pigeons, duck-billed platypuses, giant dodos.

On the television news, big-name celebrities were applauded the moment they emigrated. If these people, movie stars and rock bands, could emigrate for the greater good of all humanity, these people with money and talent and fame, with everything to keep them here, if they could emigrate, everyone could.

In the last issue of People magazine, the feature story was the “Celebrity Cruise to Nowhere.” Thousands of the best-dressed, most beautiful people, fashion designers and supermodels, software moguls and professional athletes, they boarded the Queen Mary II and sailed off, drinking and dancing, racing north across the Atlantic Ocean, looking, full speed ahead, for an iceberg to ram.

Chartered jetliners slammed into mountaintops.

Tour buses careened off towering ocean cliffs.

Here in the United States, most people went to Wal-Mart or Rite Aid and bought the Going Away Kits. The first generation of kits were barbiturates packaged inside a head-sized plastic bag with a drawstring for around your neck. The next generation of kits were a cherry-flavored chewable cyanide pill. So many people were emigrating right there in the store aisle—emigrating without paying for their kits—that Wal-Mart put the kits behind the customer-service desk with the cigarettes and made you pay first before they'd hand one over. Every couple minutes, an announcment over the public-address speakers asked customers to be courteous and not to emigrate while on store property . . . Thank you.

Early on, some people pushed what they called the French Method. Their idea was just to sterilize everyone. First by surgery, but this took too long. Then by exposing people's genitals to focused radiation. Still, by that time all the doctors had emigrated. Doctors were among the first to jump ship. Doctors, true, yes, death was their enemy, but without it they were lost. Brokenhearted. Without doctors, it was janitors shooting folks with radiation. People got burns. The power grid failed. The End.

By then, all the beautiful, cool people had emigrated with cyanide in champagne at glamorous “Bon Voyage Parties.” They'd held hands and jumped from skyscraper penthouse parties. People already a little world-weary, all the movie stars and super-athletes and rock bands. The supermodels and software billionaires, they were gone after that first week.

Every day, Eve's dad would come home saying who was gone from his office. Who in the neighborhood had emigrated. It was easy to tell. Their front lawn would get too tall. Their mail and newspapers would pile up on the doorstep. Their curtains were never open, their lights never came on, and you'd walk past and catch a whiff of something sweet, some kind of fruit or meat rotting inside the house. The air buzzed with black flies.

The house next door, the Frinks' house, was like that. So was the house across the street.

For the first few weeks, it was fun: Larry going downtown to pound his electric guitar alone on the stage of the Civic Theater auditorium. Eve getting to use the entire shopping mall as her own private closet. School was out, and it would never, ever start back up.

But their dad, you could tell he was already over Tracee. Their dad was never good at the part after the romantic start. Normal times, this was when he'd start to cheat. He'd find some new squeeze at his office. Instead, he was watching the Venus footage on television, paying close attention, his nose almost touching the parts where you could make out people, groups of those beautiful supermodel people, piled together naked or linked in a long daisy chain. Licking red wine off each other. Humping without reproduction or disease or God's damnation.

Tracee, she was making a list of celebrities she wanted to be best friends with once the family arrived. At the top of her list was Mother Teresa.

By now even harried moms were rounding up their kids, shrieking for everybody to hurry up and drink their poisoned milk and get their asses the hell to the next step of spiritual evolution. Now even life and death would be phases to rush through, the way teachers hurried kids from grade to grade to graduation—no matter how much they did or didn't learn. A big rat race to enlightenment.

In the car now, her voice getting deep and rough from breathing the smoke, Tracee reads, “As the cells of your heart valves begin to die, the two halves, called ventricles, get sloppy, pumping less and less blood through your body . . .”

She coughs and reads, “Without blood, your brain stops functioning. Within minutes you'll emigrate.” And Tracee shuts the pamphlet. The End.

Eve's dad says, “Good-bye, planet Earth.”

And the Boston terrier, Risky, barfs up cheese popcorn all over the back seat.

The smell of dog barf, and the sound of Risky gobbling it up, are even worse than the carbon monoxide.

Larry looks at his sister, the black makeup smeared around his eyes, his eyes blinking in slow motion, he says, “Eve, take your dog outside to puke.”

In case the family's gone when she gets back, her dad says there's a Going Away Kit on the counter in the kitchen. He tells Eve not to hang around too long. They'll be waiting for her at the big party.

Eve's future ex-stepmom says, “Don't hold the door open and let out any smoke.” Tracee says, “I want to emigrate, not just be brain-damaged.”

“Too late,” Eve says, and tugs the dog outside to the backyard. There, the sun is still shining. Birds build nests, too dumb to know this planet is out of fashion. Bees crawl around inside the open roses, not knowing their whole reality is obsolete.

In the kitchen, on the counter next to the sink, is a Going Away Kit, the plastic blister card of cyanide pills. It was a new flavor, lemon. A family pack. Printed on the cardboard backing is a little cartoon. It shows an empty stomach. A clock face counts off three minutes. And then your cartoon soul would wake up in a world of pleasure and comfort. The next planet. Evolved.

Eve punches one out, a bright-yellow pill printed with a smiling happy-face in red. It didn't matter if they'd used that toxic kind of red dye. Eve punches out all the pills. All eight, she takes into the bathroom and flushes down the toilet.

The car's still running inside the garage. Through a window, standing on a lawn chair, Eve can see the heads slumped inside. Her dad. Her future ex-stepmom. Her brother.

In the backyard, Risky is nosing at the crack under the garage door, sniffing the fumes from inside. Eve tells him, No. She calls him back away from the house, back into the sunshine. There, with the neighborhood quiet except for the birds, the buzz of the bees, the backyard already looks messy and needs mowing. With no roar of lawn mowers and airplanes and motorcycles, the birds singing sound as loud as traffic used to.

After she lays down in the grass, Eve pulls up the bottom of her shirt and lets the sun warm her stomach. She closes her eyes and rubs the fingertips of one hand in slow circles around her bellybutton.

Risky barks, once, twice.

And a voice says, “Hey.”

A face sticks over the fence from the backyard next door. Blond hair and pink pimples, a kid named Adam from school. From before all the schools shut down. Adam's fingers grip the top edge of the wood fence, and he pulls himself up until both elbows rest along the top. His chin hooked on his two hands, Adam says, “Did you hear about your brother's girlfriend?”

Eve shuts her eyes and says, “This sounds weird, but I really miss death . . .”

Adam kicks a leg sideways to hook his foot over the fence. He says, “Your folks emigrate yet?”

In the garage, the car's engine coughs and misses a beat on one cylinder. A ventricle getting sloppy. Inside the window glass, the garage air is shifting gray clouds of smoke. The engine misses again and goes quiet. Nothing inside moves. Eve's family, now they're just their own left-behind luggage.

And, spread out in the sunshine, feeling her skin turn tight and red, Eve says, “Poor Larry.” Still rubbing circles around her bellybutton.

Risky goes to stand next to the fence, looking up, as Adam hauls one leg, then the other over the top, then jumps down into the yard. Adam stoops to pet the dog. Scratching under the dog's chin, Adam says, “Did you tell them we're pregnant?”

And Eve, she doesn't say anything. She doesn't open her eyes.

Adam says, “If we get the whole human race started again, our folks will be so pissed . . .”

The sun is almost straight overhead. What sounds like cars is just wind blowing through the empty neighborhood.

Material possessions are obsolete. Money is useless. Status is pointless.

It would be summer for another three months, and there was a whole world of canned food to eat. That's if the Emigration Assistance Squad didn't machine-gun her for noncompliance. Top-A priority target that she is. The End.

Eve opens her eyes and looks at the white dot near the blue horizon. The Morning Star. Venus. “If I have this baby,” Eve says, “I hope it's going to be . . . Tracee.”

24

Mr. Whittier leads Miss Sneezy to the door. To the world, outside. The two of them, hand in hand. Here is our world without a devil, our Villa Diodati without any monster to blame. He's hauled the alley door open a little, open enough so a ray of real sunlight angles in from the alley. That bright slot, the opposite of the black slot we found when we arrived.

Miss Sneezy the same as Cassandra Clark, the bride of Mr. Whittier. The one he wants to save.

The projector bulb has burned out. Or burned so hot so long—with something dramatic always happening, something horrible always happening, something exciting always happening—it's tripped a circuit breaker.

The Baroness Frostbite is asleep in her pile of rags and lace, her greasy pink pucker, muttering. So is the Earl of Slander, sleep-talking, dream-rewinding the scenes in his head.

We all look to be asleep or unconscious or dreaming awake, muttering about how none of this is our fault. We're the prey. Everything here has been done to us.

Only Saint Gut-Free and Mother Nature whisper back and forth. He keeps sideways-eyeing the open door and the crack of light spilling inside. Mr. Whittier and Miss Sneezy, their dark skeletons outlined and dissolving in the glare of daylight.

The rest of us, dissolving into our costumes, into the carpet, into the floor.

Mother Nature keeps broken-record-saying, “Stop them . . . stop them . . .”

It would make a good-enough happy ending, Saint Gut-Free says. Those two young lovers walking out into the light of a bright new day. They could find help and save the group. The two of them could be victims and heroes.

But Mother Nature will only whisper, “Too early.” They need to wait just a little longer. Being younger, they can afford to wait until a few more have died.

Mother Nature and Saint Gut-Free, they could outlive old Whittier and sick Miss Sneezy.

Looking around at the rest of us, you'd bet Agent Tattletale and Chef Assassin won't last another day. The Countess Foresight, her brocade chest has stopped moving up and down, and her lips have turned blue. Even the Reverend Godless, his plucked eyebrows have stopped trying to grow back.

No, the longer they can wait, the less ways the money will have to be split.

Her brass bells ringing, the red henna vines on her hands, Mother Nature slips off one of the Saint's shoes. Her fingers touching just the pleasure centers of his sole, she holds on, her touch rolling his eyes backward in his head.

No, Mother Nature and Saint Gut-Free can have it all. All the money, she says, still touching him down there. All the glory. All the pity.

His eyes rolled up, blind, white as hard-boiled eggs, his eyelashes flutter until he jerks his foot away, Saint Gut-Free saying:

“Mnye etoh nadoh kahk zoobee v zadnetze.”

His pant legs and shirttails, they rip and stretch where they're glued to the stage with blood, and the Saint drags himself to his feet and says he's got to get out.

Not yet, says Mother Nature. Her voice a teeth-together, clenched hiss.

Saint Gut-Free takes a step and stumbles. His legs buckle, and he falls to his hands and knees. Crawling toward the open door, he says, “How can I stop them?”

And, reaching after him, Mother Nature catches her fingers hooked around his ankle and says, “Wait.”

The path where the sunlight leads them to the door, there the concrete floor feels warm. The two of them crawling, they close their eyes, blinded by the brightness, feeling their way by where the floor is warmer, Brailling with their hands and knees until they find the doorframe with the fingertips they have left. They find the sunlight with the skin of their lips and eyelids.

In the alley's narrow blue sky, birds soar back and forth. Birds and clouds that aren't cobwebs. In a blue that isn't velvet or paint.

With his head stuck out the door, Saint Gut-Free says, “I know where we're at.” Squinting, he says, “They're still here.” He points with one hand, saying, “Miss Sneezy, wait . . .”

Mother Nature's fingers holding tight to his shirt and the waist of his pants, he keeps crawling, swimming, saying, “Please, stop.”

Half out the door, his hands dragging him through the broken glass and trash of the alley, all of the beautiful garbage warm from the afternoon sun, Saint Gut-Free says, “Stop!”

While two figures stagger toward the alley's entrance: the girl close by, the old man almost a city block away, his arm raised as a taxi pulls to the curb.

Toward this, the Saint shouts, “Miss Sneezy!”

He shouts, “Wait!”

Miss Sneezy turns to look.

And . . . then . . . and . . . Shooo-rook!

The knife from the floor, the paring knife that Chef Assassin tossed at Mr. Whittier, Mother Nature's brought it with them.

That knife sticking out of Miss Sneezy's chest, it still shakes with each beat of her heart, shaking less and less as Mother Nature and Saint Gut-Free drag her back inside the door. Back into the dark.

The knife shakes less as they climb to their feet and wrestle the door shut, the metal rollers squealing. The sky, getting more narrow, until the birds and clouds and blue are gone.

In the alley, Mr. Whittier's voice shouts from closer and closer, for them to stop.

The knife shakes even less as Mother Nature says, “I told you:

“Not yet.”

And then the knife stands still. The coughing, sniffing, sneezing little person we've waited to see die from the day we arrived here—at last, dead.

We haven't so much saved the world as we've preserved our audience. Kept alive the people to watch us on television, read our books, go to our some-day movie. Our consumer base.

Saint Gut-Free holding the door shut, the lock clicks open from the outside. The knob rattling. The Saint clicks it locked, and again it clicks open.

The Saint clicks it shut, saying, “No.” And the lock clicks open, turned by a key from the outside.

Back in the dark, back in the cold, Mother Nature pulls the sticky blade out of Miss Sneezy. Mother Nature sticks the blade into the lock and snaps it off.

The lock, ruined. The knife, ruined. Poor Miss Sneezy, with her red eyes and runny nose, reduced to being a prop in our story. A person made into an object. As if you cut open a rag doll with a silly name, and found inside: Real intestines, real lungs, a beating heart, blood. A lot of hot, sticky blood.

Now the story split another less way. What was done to us.

For now, we're still here. In our dim circle around the ghost light.

The voice of Mr. Whittier, he's wailing outside the steel door. His fists, pounding. Wanting to come inside. Not wanting to die alone.

For now we wait, repeating our story in the Museum of Us. In this, our permanent dress rehearsal.

How Mr. Whittier trapped us here. He starved and tortured us. He killed us.

We recite this: the Mythology of Us.

And someday soon, any day now, the world will come open that door and rescue us. The world will listen. Starting on that sun-glorious day, the whole world is going to love us.

The Poems

Guinea Pigs

Landmarks

Under Cover

Product Improvements

Think Tank

Trade Secrets

Erosion

For Hire

Looking Back

Job Description

Babble

The Consultant

Voir Dire

Plan B

Anticipation

American Vacations

Evolution

Shortsighted

Absolution

The Interpreter

Proof

The Stories

Guts by Saint Gut-Free

Foot Work by Mother Nature

Green Room by Miss America

Slumming by Lady Baglady

Swan Song by the Earl of Slander

Dog Years by Brandon Whittier

Ambition by the Duke of Vandals

Post-Production by Mrs. Clark

Exodus by Director Denial

Punch Drunk by the Reverend Godless

Ritual by the Matchmaker

The Nightmare Box by Mrs. Clark

Civil Twilight by Sister Vigilante

Product Placement by Chef Assassin

Speaking Bitterness by Comrade Snarky

Crippled by Agent Tattletale

Dissertation by the Missing Link

Poster Child by Mrs. Clark

Something's Got to Give by the Countess Foresight

Hot Potting by the Baroness Frostbite

Cassandra by Mrs. Clark

Evil Spirits by Miss Sneezy

Obsolete by Mr. Whittier

About the Author

Chuck Palahniuk's six novels are the best-selling Diary, Lullaby, and Fight Club, which was made into a film by director David Fincher, Survivor, Invisible Monsters, and Choke. He is also the author of the best-selling nonfiction collection Stranger Than Fiction and the profile of Portland Fugitives and Refugees, published as part of the Crown Journeys series. He lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Also by Chuck Palahniuk

Invisible Monsters

Survivor

Fight Club

Choke

Lullaby

Fugitives and Refugees

Diary

Stranger Than Fiction

PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY

A division of Random House, Inc.

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Palahniuk, Chuck.

Haunted: a novel of stories / Chuck Palahniuk.– 1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Artists—Fiction. 2. Prisoners—Fiction. 3. Torture victims—Fiction. 4. Social isolation—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3566.A4554H38 2005

813'.54—dc22

2004059380

Copyright © 2005 by Chuck Palahniuk

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

All Rights Reserved

eISBN: 978-0-385-51583-2

v3.0