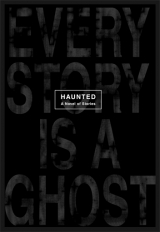

Текст книги "Haunted"

Автор книги: Charles Michael «Chuck» Palahniuk

Жанр:

Повесть

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

He was the hero we didn't want.

On September 10, civil twilight was at 8:34, and a moment later, Curtis Hammond turned toward a noise. His tie loose, he squinted into the dark. Smiling, his teeth shining, he said, “Hello?”

14

We find Comrade Snarky collapsed on the carpet in front of a tapestry sofa in the second-balcony foyer. Her face, blue-white, framed by the pillow of her crusty, gray wigs. The wigs piled and pinned together. None of her moving. Her hands are bones beaded together with tendon inside the flesh of her black velvet gloves. The cords of her thin neck look webbed with skin. Her cheeks and each closed eye look caved in, sunken and hollow.

She's dead.

Her eyes, the pupils stay the same pinhole size when the Earl of Slander thumbs her eyelids up. We check her arms for rigor mortis, her skin for stippling and settled blood, but she's still fresh meat.

Our royalties only have to split fourteen ways now.

The Earl of Slander thumbs the eyes shut.

Thirteen ways, if Miss Sneezy keeps coughing. Twelve ways, if the Matchmaker gets the courage to chop off his dick.

Now Comrade Snarky's a permanent member of the supporting cast. A tragedy the rest of us get to tell. How she was so brave and kind, now that she's dead. Just a prop in our story.

“If she's dead—she's food,” Miss America says. She stands at the top of the lobby stairs, one hand holding the golden railing. Her other hand holds her belly. “You know she'd eat you,” she says. Clutching the railing, supported by fat cupids painted gold, Miss America says, “She'd want us to.”

And the Earl of Slander says, “Roll her over, if that makes it easier. So you can't see her face.”

So we roll her over, and Chef Assassin kneels on the carpet and digs the layers of skirts and petticoats, muslin and crinoline, up around her waist to show yellow cotton panties sagged across her flat, pale ass. He says, “You sure she's dead?”

Miss America leans down and slips two fingers against the side of Comrade Snarky's webbed neck, inside the high lace collar, pressing the blue-white skin. Chef Assassin watches this, kneeling there, holding his boning knife, one finger-long blade of steel. His free hand holds back the drift of white and gray lace, yellow muslin, the pile of petticoats and skirts. He looks at the blade and says, “Think we should sterilize this?”

“You're not taking out her appendix,” Miss America says, her two fingers still tight against the side of the blue-white neck. “If you're worried,” she says, “we can just cook the meat longer . . .”

In a way, the Donner Party was lucky, says the Earl of Slander, still scribbling in his notepad. So was the plane full of South American rugby players who crash-landed in the Andes in 1972. They were luckier than us. They had the cold weather on their side. Refrigeration. When somebody died, they had time to debate the finer points of acceptable human behavior. You just buried anybody dead in the snow until everyone was so hungry it didn't matter.

Here, even in the basement, even in the subbasement with Lady Baglady's and Mr. Whittier's and the Duke of Vandals' velvet-wrapped bodies, it's not freezing cold. If we don't eat now, before the bacteria inside Comrade Snarky begin their own chow-down, she'll be wasted. Swollen and putrefied. Poisoned so much no amount of turning around and around in the microwave oven will ever make her into food again.

No, unless we do this—butcher her, here and now, on these gold-and-flower carpets beside the tapestry sofas and crystal light-sconces of the second-balcony lobby, it will be one of us here, dead, tomorrow. Or the next day. Chef Assassin with his boning knife will be cutting our underwear up the back to show our withered-flat, blue-white butt and little-stick thighs. The back of each knee turned gray.

One of us, just meat about to go bad.

On one flat ass cheek, the panty fabric peels back to show a tattoo, a rose in full bloom. Just like she said.

Those rugby players lost in the Andes, it's from reading their book that Chef Assassin knows to carve up the buttocks first.

Miss America pulls her two fingers back from the cold neck, and she stands up. She blows on the fingers, warm breath, then rubs her hands together fast and stuffs them in the folds of her skirt. “Snarky's dead,” she says.

Behind her, Baroness Frostbite turns toward the stairs that lead down to the lobby. Her skirts rustling and dragging, her voice trailing away, she says, “I'll get a plate or a dish you can use.” She says, “How you present food is so important,” and she's gone.

“Here,” Chef Assassin says, “somebody hold this shit back off me.” And he elbows the pile of skirts and stiff fabric that wants to fall where he has to work.

The Earl of Slander steps over the body, straddling it at the waist, looking at its feet. The legs disappear inside white socks rolled to halfway up each stringy calf bone wiggling with veins, the feet in red high heels. The Earl of Slander gathers the skirts in both arms and crouches down, holding them back. With a sigh, he sits down, his butt settling on Comrade Snarky's dead shoulder blades, his knees pointed up at the ceiling, his arms lost in the drift of her skirts and lace. The little-mesh microphone sticking out of his shirt pocket. The little RECORD light, glowing red.

And with one hand, the fingers spread, Chef Assassin holds the skin on one buttock tight. And with his other hand, he drags the knife down. As if he's drawing a straight line down Comrade Snarky's blue-white ass, a line that gets thicker and bolder the longer he draws it. Pulling the knife parallel with the crack of her ass. The line looks black against the blue-white skin, red-black until it drips, red, onto the skirts under her. Red on the blade of the boning knife. The red, steaming. Chef Assassin's hands red and steaming, he says, “Is a dead person supposed to bleed this much?”

Nobody says anything.

One, two, three, four, somewhere else, Saint Gut-Free whispers, “Help us!”

Chef Assassin's elbow is bobbing up and down as he saws, sawing the little blade in and out of the red mess. His original straight line lost in the red stew. The steam rising with the blood smell of Tampax, that women's-bathroom smell in the cold air. His sawing stops, and one hand lifts a scrap of something red. His eyes don't follow it. His eyes stay on the mess, red in the center of this snowdrift of petticoats. This big steaming flower, here on the carpet of the second-balcony foyer. Chef Assassin shakes the red scrap in his raised hand. What he can't look at, dripping and running with dark red. And he says, “Take it. Somebody . . .”

Nobody's hand reaches out.

Her rose tattoo, there, in the center of the scrap.

And, still not looking at it, Chef Assassin shouts, “Take it!”

A rustle of fairy-tale satin and brocade skirts, and Baroness Frostbite is back among us. She says, “Oh my God . . .”

A paper plate hovers under the dripping red scrap, and Chef Assassin drops it. On the plate, it's meat. A thin steak. The way a cutlet looks. Or those long scraps of meat labeled “strip steaks” in the butcher's case.

Chef Assassin's elbow is bobbing again, sawing. His other hand lifts scrap after dripping scrap out of the steaming red center of that huge white flower. The paper plate is piled high and starting to fold in half from the weight. Red juice spilling off one edge. The Baroness goes to get another plate. Chef Assassin fills that, too.

The Earl of Slander, still sitting on the back of the body, he shifts his weight, pulling his face away from the steaming mess. Not the nothing smell of cold, clean meat from the supermarket. This is the smell of animals half run-over and smearing a path of shit and blood as they drag their shattered back legs off a hot summer highway. Here's the messy smell of a baby the moment after it's born.

Then the body, Comrade Snarky, lets out a little moan.

It's the soft groan of someone dreaming in her sleep.

And Chef Assassin falls backward, both hands dripping. The knife left behind, jutting straight up from the flower's red center—until the dropped skirts flutter, lower, sift down to hide the mess. The Baroness drops the first paper plate, burdened with meat. The flower closing. The Earl of Slander springs to his feet, and he's off her. We, we're all standing back. Staring. Listening.

Something needs to happen.

Something needs to happen.

Then, one, two, three, four, somewhere else, Saint Gut-Free whispers, “Help us!”

The soft, regular foghorn of his voice.

From somewhere else, you hear Director Denial calling, “Here . . . kitty, kitty, kitty . . .” Her words stretched long and then broken by sobs, she says, “Come . . . to Mama . . . my baby . . .”

His hands webbed with gummy red, Chef Assassin flexes his fingers, not touching anything, just staring at the body, he says, “You told me . . .”

And Miss America crouching forward, her leather boots creak. She slides two fingers into the lace collar and presses the side of the blue-white neck. She says, “Snarky's dead.” She nods at the Earl of Slander and says, “You must've forced some air out of her lungs.” She nods at the meat spilled off the plate, now breaded with dust and lint on the foyer carpet, and Miss America says, “Pick that up . . .”

The Earl of Slander rewinds his tape, and Comrade Snarky's voice moans and moans the same moan. Our parrot. Comrade Snarky's death taped over the Duke of Vandals' taped over Mr. Whittier's taped over Lady Baglady's death.

How Comrade Snarky died was probably a heart attack. Mrs. Clark says it's from a shortage of thiamine, what we call vitamin B1. Or it could've been a shortage of potassium in her bloodstream, causing muscle weakness and, again, a heart attack. That was how Karen Carpenter died in 1983, after years of anorexia nervosa. Fainted dead on the floor like this. Mrs. Clark says it was no doubt a heart attack.

Nobody really dies of starvation, Mrs. Clark says. They die of pneumonia brought on by malnutrition. They die of kidney failure brought on by low potassium. They die of shock caused by bones broken by osteoporosis. They die of seizures caused by lack of salt.

However she died, Mrs. Clark says, that's how most of us will. Unless we eat.

At last, our devil commands us. We're so proud of her.

“Easy as skinning a chicken breast,” Chef Assassin says, and he drops another lump of meat on the dripping paper plate. He says, “Christ Almighty, I do love these knives . . .”

Plan B

A Poem About Chef Assassin

“To become a household word,” says Chef Assassin, “all you need is a rifle.”

This he learned early, watching the news. Reading the paper.

Chef Assassin standing onstage, he wears those black-and-white-checkered pants

that only professional cooks get to wear.

Billowing big, but still stretched tight to cover his ass.

His hands, his fingers, a patchwork of scabs and scars. Shiny old burns.

His white shirtsleeves rolled up,

and all the hair singed off the muscle of his forearms.

His thick arms and legs that don't bend

so much as they fold at the knee and elbow.

Onstage, instead of a spotlight, a movie fragment flickers:

where two close-up hands, the fingernails clean and the palms perfect

as a pair of pink gloves,

they skin a chicken breast.

His face, a round screen, lost under a layer of fat, his mouth lost under the pastry brush

of a little mustache,

Chef Assassin says, “That's my backup plan.”

The Chef says, “If my garage band never gets a record contract—”

if his book never finds a publisher—

if his screenplay never gets a green light—

if no network picks up his pilot episode—

The Chef, his face worms and twitches with those perfect hands:

skinning and boning,

pounding and seasoning,

breading and frying and garnishing,

until that piece of dead flesh looks too pretty to eat.

A gun. A scope. Good aim and a motorcade.

What he learned as a kid, watching the news on television, every night.

“So I'm not forgotten,” the Chef says.

So his life isn't wasted.

He says, “That's my Plan B.”

Product Placement

A Story by Chef Assassin

To Mr. Kenneth MacArthur

Manager of Corporate Communications

Kutting-Blok Knife Products, Inc.

Dear Mr. MacArthur,

Just so you know, you make a great knife. An excellent knife.

It's tough enough doing professional kitchen work without tolerating a bad knife. You go to do a perfect potato allumette, that's thinner than a pencil. Your perfect cheveu cut, that's about as big around as a wire—that's half as thick as a potato chip. You make your living cutting carrots brunoisette with hot sauté pans already waiting with butter, people yelling for those potatoes cut minunette, and you learn quick the difference between a bad knife and a Kutting-Blok.

The stories I could tell you. Time and time again, how your knives have pulled my ass out of the fire. You chiffonade Belgian endive for eight hours, and you might get some idea what my life is like.

Still, it never fails, you can tourné baby carrots all day, carving each one into a perfect orange football, and the one you screw up, that carrot lands on the plate of some failed cook, some nobody with a community-college degree in hospitality services, just a piece of paper, who now thinks he's a restaurant critic. Some prick who hardly knows how to chew and swallow, and he's writing in next week's paper how the chef at Chez Restaurant is lousy at tourné-ing carrots.

Some bitch no caterer would even hire to flute mushrooms, she's putting in print how my bâtonnet parsnips are too thick.

These sellouts. No, it's always easier to nitpick than actually to cook the meal.

Every time somebody orders the dauphinoise potatoes or the beef Carpaccio, please know that someone in our kitchen says a little prayer of thanks for Kutting-Blok knives. The perfect balance of them. The riveted handle.

Sure, knock wood, we would all like to make more money for less work. But selling out, turning critic, setting yourself up as a know-it-all, and taking cheap shots at the people still trying to make their living peeling calf tongue . . . paring away kidney fat . . . pulling off liver membrane . . . while those critics sit in their nice clean offices and type their gripes with nice clean fingers—that's just not right.

Of course, this is just their opinion. But there it is, showcased next to real news—famines and serial killers and earthquakes—there it's given the same-sized type. Somebody's gripe that their pasta wasn't quite al dente. As if their opinion is an Act of God.

A negative guarantee. The opposite of an advertisement.

To my mind, those who can, do. Those who can't, gripe.

Not journalism. Not objective. Not reporting, but judging.

These critics, they couldn't cook a great meal if their life depended on it.

It's with this in mind I started my project.

No matter how good you are, working in a kitchen is a slow death by a million tiny knife cuts. Ten thousand little burns. Scalds. Standing on concrete all night, or walking across greasy or wet floors. Carpal tunnel, nerve damage from stirring and chopping and spooning. Deveining an ocean of shrimp under ice water. Knee pain and varicose veins. Wrist and shoulder repetitive-motion injuries. A career of perfect calamares rellenos is a lifelong martyrdom. A lifetime spent turning out the ideal ossobuco alla milanese is a long, slow death by torture.

Still, no matter how thick-skinned you are, getting picked apart in public by some newspaper or Internet writer does not help.

Those online critics, they're a dime a dozen. Everybody with a mouth and a computer.

That's what all my targets have in common. It's a blessing the police don't work a little closer together. They might notice a freelance writer in Seattle, a student reviewer in Miami, a Midwestern tourist posting his opinion on some travel Web site . . . There is a pattern to my sixteen targets, so far. Yes, and there's my years of motivation.

There's not much difference between boning a rabbit and a snarky Web-site blogger who said your costatine al finocchio needed more Marsala.

And thanks to Kutting-Blok knives. Your forged tourné knives do both jobs beautifully, without the hand and wrist fatigue you might get using a less expensive, stamped paring knife.

Likewise, cleaning a skirt steak and skinning the little weasel who posted an article about how your beef Wellington was ruined with too much foie gras, both jobs go fast and effortless thanks to the flexible blade of your eight-inch filleting knife.

Easy to sharpen and easy to clean. Your knives are a blessing.

It's the targets that always turn out to be such a disappointment. No matter how little you expect when you meet these people in person.

All it takes is a little praise to arrange a get-together. Imply the kind of sexual partner they might want. Better yet, imply you're the editor of a national magazine, looking to take their voice worldwide. To exalt them. Give them the glory they so richly deserve. Lift them to prominence. All that attention crap, offer them half that and they'll meet you in any dark alley you can name.

In person, their eyes are always so small, each eye like a black marble stuck into a fat man's bellybutton. Thanks in part to Kutting-Blok knives, they look better, cleaned and dressed and trimmed. Meat, ready for some good use.

After you've pulled the cold viscera out of a hundred guinea hens, it's no big deal, slitting the belly of a freelance writer who wrote in some regional entertainment guide that your escarole-feta turnovers were too chewy. No, the Kutting-Blok ten-inch French knife makes even that task as easy as gutting a trout or salmon or any round fish.

It's odd, the parts that stand out in your mind. A look at someone's thin, white ankle, and you can see who she must've been as a girl in school, before she learned to make her living by attacking food. Or another critic, who wore his brown shoes polished bright as the caramel crust on a crème brûlée.

It's this same attention to detail that you put into every knife.

This is the care and attention I used to put into my kitchen work.

Still, no matter how careful I am, it's just a matter of time before the police will catch me. With this in mind, my only fear is that Kutting-Blok knives will become linked in the public mind with a series of deeds that people might misunderstand.

Too many people will see my preference as a kind of endorsement. Like Jack the Ripper doing a television commercial.

Ted Bundy for Such & Such Brand rope.

Lee Harvey Oswald pitching Such & Such Brand rifle.

A kind of negative endorsement, true. Maybe even something that would hurt your market share and net sales. Especially in the upcoming retail Christmas season.

It's standard procedure at all major newspapers, the moment they hear about a big jetliner disaster—a midair collision, a hijacking, a runway crash—they know to pull all the big display advertisements for airlines that day. Because, within minutes, every airline will call to cancel their ad, even if it means paying full price for a space they won't use. A space filled at the last moment with a freebie promo ad for the American Cancer Society or Muscular Dystrophy. Because no airline wants to risk being associated with the day's bad, bad news. The hundreds dead. Being linked that way in the public mind.

It takes very little effort to recall what the so-called Tylenol Murders did for that product's stock. With seven people dead, just the 1982 recall of their product cost Johnson & Johnson $125 million.

That kind of negative endorsement, it's the opposite of an advertisement. Like what critics do with their snide reviews, printed only to show how clever and bitter they've become.

The details of each target, including the knife used, it's all still so fresh in my mind. It would take very little effort for the police to make me confess, to make it public record, the wide variety of your excellent knives I've used and for what purpose.

Forever after, people will refer to the “Kutting-Blok Knife Murders” or the “Kutting-Blok Serial Killings.” Your company is so much better known than anonymous little me. You have a knife in so many kitchens, already. It would be a horrible shame to see your generations of quality and hard work wrecked because of my project.

Please bear in mind, food critics don't buy many knives. Knock on wood, but industry sympathy in this case might well be with me. Me, a grass-roots hero. You never know.

Any small investment you can make, it will benefit us both.

The more resources you can provide me to evade capture, the less likely it will be that this unfortunate fact is ever known to the average knife-consumer. A gift of as little as five million dollars would allow me to emigrate and live unnoticed in another country, far, far outside your market demographic. That money will guarantee your company a steady rise into a bright future. For me, the money will allow me to retrain in a new field of work, a new career.

Or, for as little as one million dollars, I will switch to Sta-Sharp knives—and if arrested will swear I've used only their substandard products throughout my project . . .

One million dollars. How's that for brand loyalty?

To contribute, please run a display advertisement this upcoming Sunday, in your local daily newspaper. Upon seeing that ad, I will contact you about accepting your help. Until then, I must continue with my work. Otherwise, you can expect another target.

Thank you for considering my request. I look forward to hearing from you, soon.

In this world, where so few people will devote their lives to producing a product of lasting quality, I applaud you.

I remain, as always, your biggest fan,

Richard Talbott