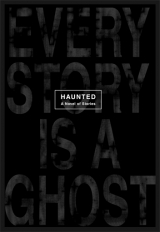

Текст книги "Haunted"

Автор книги: Charles Michael «Chuck» Palahniuk

Жанр:

Повесть

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

These angels of mercy. These angels of charity.

Those foolish, foolish angels.

And the nurse or orderly will say, “Most of us did . . . have that kind of pep.” Walking away, the nurse will say, “When we were his age.”

He's not old.

Here's how the truth always leaks out.

Mr. Whittier, he suffers from progeria. The truth is, he's eighteen years old, a teenager about to die of old age.

One out of eight million kids develops Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. A genetic defect in the protein lamin A will make their cells fall apart. Aging them at seven times the normal rate. Making teenaged Mr. Whittier, with his crowded teeth and big ears, his veined skull and bulging eyes, making his body 126 years old.

“You could say . . . ,” he always tells the angels, waving away their concern with one wrinkled hand, “you could say I'm aging in dog years,”

In another year, he'll be dead of heart disease. Of old age, before he's twenty.

After this, the angel doesn't turn up for a while. The truth is, it's just too sad. Here's a kid, maybe younger than one of her own teenagers, dying alone in a nursing home. This kid, still so full of life and reaching out for help, to the only people around—to her—before it's too late.

This is too much.

Still, every yoga class, every PTA meeting, each time she looks at a teenager, this angel wants to cry.

She has to do something.

So she goes back, with her smile toned down a little. She tells him, “I understand.”

She smuggles in a pizza. A new video game. She says, “Make a wish, and I'll help make it come true.”

This angel, she wheels him out a fire exit for a day riding rollercoasters. Or hanging out at the mall. This teenaged geezer and a beautiful woman, old enough to be his mother. She lets him slaughter her at paintball, the colors wrecking her hair. His wheelchair. She takes a dive at laser tag. She half carries his wrinkled half-naked carcass to the top of a waterslide, again and again, all of one hot, sunny afternoon.

Because he's never been high, the angel steals dope from her kid's stash box and teaches Mr. Whittier how to use a bong. They talk. Eat potato chips.

The angel, she says her husband has become his career. Her kids are growing away from her. Their family is falling apart.

Mr. W., he says his own folks, they couldn't cope. They have four other kids to raise. It's the only way they could afford the nursing home, by making him a ward of the court. After that, they'd show up and visit less and less.

And telling that, with some soft guitar ballad playing, Mr. W. will start to cry.

The one wish he wanted most was to love someone. To really make love. Not die a virgin.

Right then, the tears still rolling down from his stoner-red eyes, he'd say, “Please . . .”

This wrinkled old kid, he'd sniff and say, “Please, stop calling me Mister.”

The angel stroking his bald, spotted head, he'd tell her, “My name is Brandon.”

And he'd wait.

And she'd say it:

Brandon.

Of course, after that, they'd fuck.

Her, gentle and patient. The Madonna and the whore. Her long, yoga-trained legs spread to this naked, wrinkled goblin.

Her, the altar and the sacrifice.

Never as beautiful as she looked, next to his spotted, veined old skin. Never as powerful as she felt, as he drooled and trembled over her.

And, damn—for a virgin—if he didn't take his own sweet time. He'd started missionary-style, then had one of her legs in the air, splitting the reed. Then both her feet, gripped tight around the ankles and framing his panting face.

Thank God for the yoga.

Viagra-hard, he rode her on all fours, doggy-style, even taking himself out and poking at her ass until she said to stop. She was sore and stoned, and as he bent her legs to force her feet up, behind her head, by then her bright, fake angel's smile had come back.

After all that, he came. In her eyes. In her hair. He asked her for a cigarette she didn't have. Taking the bong off the floor beside the bed, he torched another bowl and didn't offer her a hit.

The angel, she got dressed and tucked her kid's bong under her coat. She knotted a scarf around her sticky hair and started to leave.

Behind her, as she opened the door to the hallway, Mr. Whittier was saying, “You know, I ain't ever had a blow job before, neither . . .”

As she stepped out of the room, he was laughing. Laughing.

After that, she'd be driving, and her cell phone would ring. It would be Whittier suggesting bondage, better drugs, blow jobs. And when the angel finally told him, “I can't . . .”

“Brandon . . .” he'd tell her. “The name's Brandon.”

Brandon, she'd say. She couldn't see him, not anymore.

It's then he'd tell her—he lied. About his age.

Over the phone, she'd say, “You don't have progeria?”

And Brandon Whittier would say, “I'm not eighteen years old.”

He wasn't eighteen, and he had the birth certificate to prove it. He was thirteen years old. Now a victim of statutory rape.

But, for enough cash money, he wouldn't squeal to the cops. Ten grand, and she wouldn't suffer through an ugly courtroom drama. Front-page headlines. All her lifetime of good works and investments reduced to nothing. All for a quick fuck with a little kid. Worse than nothing—her the pedophile, now a sex criminal who would need to register her whereabouts for the rest of her life. Maybe get divorced and lose her kids. Sex with a minor carried a mandatory five-year prison sentence.

On the other hand, in another year he'd be dead of old age. Ten grand was a small price to pay for the rest of her life.

Ten grand and maybe just one little knob job for old times' sake . . .

So of course she paid. They all paid. All the volunteers. The angels.

None of them ever went back to the old-folks' home, so they never met each other. To each angel, she was the only one. Really, there were a dozen or more.

And the money? It just kept piling up. Until Mr. Whittier was too old and tired and bored to just fuck.

“Look at the stains in the lobby carpet,” he said. “See how those stains have arms and legs?”

The same as the volunteer ladies, we were trapped by a boy in the body of an old man. A thirteen-year-old kid dying of old age. The part about his family abandoning him, that much was true. But Brandon Whittier was no longer dying ignored and alone.

And, the same way he'd bagged one angel after another, this wasn't his first experiment. We weren't his first batch of guinea pigs. And—until one of those stains came back to haunt him—he told us, we would not be his last.

7

Morning starts with a woman yelling. The woman's voice, the shouting, is Sister Vigilante. Between each shout, you can hear the butt of a fist pound on wood. You can hear a wooden door boom and bounce in its frame. Then the yelling again.

Sister Vigilante yells, “Hey, Whittier!” Sister Vigilante shouts, “You're late with the fucking sunrise . . . !”

Then the fist, pounding.

Outside our rooms, our backstage dressing rooms, the hallway is dark. Beyond that, the stage and auditorium are dark. Pitch-dark except for the ghost light.

We're each getting up, grabbing some clothes, not sure if we've been asleep an hour or a night.

The ghost light is a single bare bulb on a pole that stands center stage. Tradition says it keeps any ghost from moving in when a theater is empty and dark.

In theaters before electricity, Mr. Whittier would say, the ghost light acted as a pressure-relief valve. It would flare and burn brighter, to keep the place from exploding if there was a surge in the gas lines.

Either way, the ghost light meant good luck.

Until this morning.

First it's the yelling that wakes us. Then it's the smell.

Here's the sweet smell of the black muck Lady Baglady might find slumming in the bottom of a Dumpster. It's the smell of a garbage truck's gummy, sticky back mouth. The smell of swallowed dog mess and old meat. Chewed and swallowed and packed tight together. The smell of old potatoes melting into a black puddle under the kitchen sink.

Holding our breath, trying not to smell, we're feeling our way out our doors and down the black hallway, through the dark, toward all the yelling.

Here, night and day are a matter of opinion. Until now, we just agreed to trust Mr. Whittier. Without him, whether it's a.m. or p.m. is a matter for debate. No light comes from the outside. No telephone signals. No sounds.

Still pounding the door, Sister Vigilante shouts, “Civil dawn was eight minutes ago!”

No, a theater is built to exclude the outside reality and allow actors to build their own. The walls are double layers of concrete with sawdust packed between them. So no police siren or subway rumble can wreck the spell of someone's fake death onstage. No car alarms or jackhammer can turn a romantic kiss into a belly laugh.

Each sunset is just when Mr. Whittier looks at his watch and says good night. He climbs up to the projection booth and throws the breakers, blacking out the lights in the lobby, the foyers, the salons, then the galleries and lounges. The darkness herds us toward the main auditorium. This twilight, it falls room by room until the only light left is in the dressing rooms, backstage. There, each of us sleeps. Each room with one bed, one bathroom, a shower, and a toilet. Room enough for one person and one suitcase. Or wicker hamper. Or cardboard box.

Morning is when we hear Mr. Whittier in the hallway outside our rooms, shouting good morning. A new day is when the lights come back on.

Until this morning.

Sister Vigilante shouts, “This is a law of nature you're violating . . .”

Here, with no windows or daylight, the Duke of Vandals says we could be trapped in an Italian Renaissance space station. We could be deep underwater in an ancient Mayan submarine. Or what the Duke calls a Louis XV coal mine or bomb shelter.

Here, in the middle of some city, inches away from the millions of people walking and working and eating hot dogs, we're cut off.

Here, anything that looks like a window, draped with velvet and tapestry, or fitted with stained glass, it's fake. It's a mirror. Or the dim sunlight behind the stained glass is lightbulbs small enough to make it always dusk in the tall arched windows of the Gothic smoking room.

We still hunt for ways out. We still stand at the locked doors and scream for help. Just not too hard or too loud. Not until our story would make a good movie. Until each of us becomes a character skinny enough for a movie star to play.

A story to save us from all the stories of our past.

In the hallway outside Mr. Whittier's dressing room, Sister Vigilante slams a fist on the door, shouting, “Hey, Whittier! You got a lot to answer for this morning,” and you can see the Sister's breath puffing steam with every word.

The sun hasn't come up.

The air is cold and stinks.

The food is gone.

The rest of us, together, we tell Sister Vigilante: Shush. People outside might hear and come to our rescue.

A lock clicks, and the dressing-room door swings open to show Mrs. Clark in her stretched terry-cloth bathrobe. Her eyelids red and half open, she steps out, into the hallways, and shuts the door behind her back.

“Listen, lady,” Sister Vigilante says. “You need to treat your hostages better.”

The Duke of Vandals stands beside her. The same Duke of Vandals who went to the basement last night and sawed a bread knife through all the wires feeding into the furnace blower.

Mrs. Clark rubs her eyes with one hand.

From behind his camera, Agent Tattletale says, “Do you realize what time it is?”

Into the Earl of Slander's tape recorder, Comrade Snarky says, “Do you know there's no hot water?”

Comrade Snarky, the one who traced the copper pipes along the basement ceiling, following them back to the boiler for heating water, where she shut off the gas. She should know. She pried the handle off the gas valve and dropped the handle through a drain in the concrete floor.

“We're going on strike,” skinny Saint Gut-Free says. “We're not writing any brilliant, amazing Frankenstein shit unless we get some heat.”

This morning: No heat. No hot water. No food.

“Listen, lady,” the Missing Link says. His beard almost scours Mrs. Clark in the forehead, he stands so close in the narrow hallway outside the dressing rooms. He slides the fingers of one hand under the lapel of her bathrobe. Leaning to press her chest flat with his, the Missing Link's hand makes a fist, and he bends his elbow to lift her off the floor by that fistful of flannel.

Mrs. Clark, her slipper feet kicking in air, her hands grabbing around the hairy wrist that holds her, her eyes bug out, driving her head backward until her hair hits the closed door. Her head hits the door with a boom.

Shaking her in his fist, the Missing Link says, “You tell old man Whittier he needs to get us some food. And get us some heat. Or get us out of here—now.”

Us: the innocent victims of that oversleeping, evil, kidnapping madman.

In the blue velvet lobby, we'll have nothing for breakfast.

Bags holding anything made with liver, they were pincushioned with ten or fifteen holes. Everyone had to punch that ballot.

Out in the lobby, every silver Mylar pillow, it's gone flat. All of us with the same idea.

Even with the furnace not working, the air already cold, the food's gone bad.

“We need to wrap him,” Mrs. Clark says. To wrap him and carry the body to the deepest subbasement with Lady Baglady.

“That smell,” she says, “it's not the food.”

We don't ask the details of how he died.

It's better Mr. Whittier died offstage. This way leaves us to script the worst: His eyes rolling to watch his belly swell bigger and bigger in the night, until he can't see his feet. Until some membrane or muscle splits, inside, and he feels the rush of warm food flood against his lungs. Against his liver and heart. Next, he'd feel the chills of shock. The gray hair on his chest would turn swampy with cold sweat. His face, running with sweat. His arms and legs shake with the cold. The first signs of coma.

No one will believe Mrs. Clark, now that she's the new villain. Our new evil supervixen oppressor.

No, we get to stage this scene. We'll have him screaming with delirium. Mr. Whittier will be bleached pale and hiding behind his spread fingers, saying the devil is after him. He'll be screaming for help.

He'll lapse into his coma. And die.

Saint Gut-Free with his complicated words about the peritoneum, the duodenum, the esophagus, he'll know the official term for what went wrong.

In our version, we'll kneel at Whittier's bedside, to pray for him. Poor, innocent us, starving and trapped here but still praying for our devil's eternal soul. Then a soft-focus dissolve and toss to commercial.

That's a scene from a hit movie. A scene with Emmy nomination written all over it.

“That's the nicest thing about dead people,” says the Baroness Frostbite, putting lipstick on top of her lipstick. “They can't correct you.”

Still, a good story means no heat. Slow starvation means no breakfast. Dirty clothes. Maybe we're not as brainy-smart as Lord Byron and Mary Shelley, but we can tolerate some shit to make our story work.

Mr. Whittier, our old, dead monster.

Mrs. Clark, our new monster.

“Today,” the Matchmaker says, “is going to be a long, long day.”

And Sister Vigilante holds up one hand, her wristwatch glowing radium-green in the dim hallway. Sister Vigilante shakes the watch to make it flash, and she says, “Today is going to be as long as I say it will be . . .”

To Mrs. Clark, she says, “Now show me how to turn on the damned lights.”

And the Missing Link drops her slipper feet to the floor.

Clark and the Sister, they feel their way off into the darkness, patting the damp hallway walls, moving toward the gray of the ghost light onstage.

Mr. Whittier, our new ghost.

Even Saint Gut-Free's stomach growls.

To shrink their stomachs, Miss America says some women will drink vinegar. That's how bad hunger pangs can hurt.

“Tell me a story,” Mother Nature says. She's lit an apple-cinnamon candle with bite marks in the wax. “Anybody,” she says. “Tell me a story to make me never want to eat, ever again . . .”

Director Denial hugs her cat, saying, “A story might ruin your appetite, but Cora is still hungry.”

And Miss America says, “Tell that cat, in a couple days he'll qualify as food.” Already, her pink spandex boobs look bigger.

And Saint Gut-Free says, “Please, can anybody please take my mind off my stomach.” His voice different, smooth and dry, for the first time without food in his mouth.

The stink is thick as fog. That smell no one wants to breathe.

And, walking toward the stage, toward the circle around the ghost light, the Duke of Vandals says, “Before I ever sold a painting . . .” He looks back to make sure we'll follow, and the Duke says, “I used to be the opposite of an art thief . . .”

While, room by room, the sun starts to come up.

And in our heads, we all write this down: The opposite of an art thief . . .

For Hire

A Poem About the Duke of Vandals

“Nobody calls Michelangelo the Vatican's bitch,” says the Duke of Vandals,

just because he begged Pope Julius for work.

The Duke onstage, his scruffy jaw, scrub brush with pale stubble,

it goes round and round, kneading and grinding

a wad of nicotine gum.

His gray sweatshirt and canvas pants are flecked with dried raisins of red, dark-red,

yellow, blue and green, brown, black and white paint.

His hair tumbles behind him, a tangle of brass wire, tarnished dark with oil

and dusted with sticky flakes of dandruff.

Onstage, instead of a spotlight, a movie fragment:

a slide show of portraits and allegories, still lifes and landscapes.

All of this ancient art, it uses his face, his chest, his stocking feet in sandals

as a gallery wall.

The Duke of Vandals, he says, “No one calls Mozart a corporate whore”

because he worked for the Archbishop of Salzburg.

After that, then wrote The Magic Flute,

wrote Eine kleine Nachtmusik,

paid by trickle-down cash from Giuseppe Bridi and his big-money silk industry.

Nor do we call Leonardo da Vinci a sellout,

a tool,

because he slopped paint for gold from Pope Leo X and Lorenzo de' Medici.

“No,” says the Duke, “We look at The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa

and never know who paid the bills to create them.”

What matters, he says, is what the artist leaves behind, the artwork.

Not how you paid the rent.

Ambition

A Story by the Duke of Vandals

One judge called it “malicious mischief.” Another judge called it “destruction of public property.”

In New York City, after the guards caught him in the Museum of Modern Art, the judge reduced the charge to “littering” as a final insult. After the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the judge called what Terry Fletcher did “graffiti.”

At the Getty or the Frick or the National Gallery, Terry's crime was always the same. People just couldn't agree on what to call it.

None of these judges should be confused with the Honorable Lester G. Myers of the Los Angeles County District Court, art collector and downright nice guy. The art critic is not Tannity Brewster, writer and knower of all things cultural. And relax, no way is the gallery owner Dennis Bradshaw, famous for his Pell/Mell Gallery, where just by coincidence people get shot in the back. Every once in a while.

No, any resemblance between these characters and anyone living or dead is a complete accident.

What happens here is all made up. No one is anyone except Mr. Terry Fletcher.

Just keep telling yourself this is a story. None of this is for real.

The basic idea came from England, where art students go to the post office and take stacks of the cheap address labels available at no charge. Every post office has stacks and stacks of these labels, each one the size of your hand with the fingers straight but held tight together. A size easy to hide in your palm. The labels had a peel-off backing of waxed paper. Under that was a layer of glue designed to stick to anything, forever.

That was their real charm. Young artists—nobodies, really—they could sit in their studio and paint a perfect miniature. Or sketch a charcoal study after painting the sticker with a base coat of white.

Then, sticker in hand, they'd go out to hang their own little show. In pubs. In train carriages. The back seats of taxicabs. And their work would “hang” there for longer than you'd guess.

The post office made the stickers with such cheap paper that you could never peel them away. The paper tore in specks and flakes at the edge, but even there, the glue would stay. The raw glue, looking lumpy and yellow as snot, it collected dust and smoke until it was a black smear so much worse than the little art-school painting it had been. Folks found that any artwork was better than the ugly glue it left behind.

So—people let the art hang. In elevators and toilet stalls. In church confessionals and department-store fitting rooms. Most of these, places where a few paintings might help. Most of the painters just happy to have their work seen. Forever.

Still—leave it to an American to take something too far.

For Terry Fletcher, the big idea came while he stood in line to see the Mona Lisa. The closer he got, the painting never got any bigger. He had art textbooks that were bigger. Here was the most famous painting in the world, and it was smaller than a sofa cushion.

Anywhere else, it would be so easy to slip inside your coat and cross your arms over. To steal.

As the line crept closer to the painting, it didn't look like such a miracle, either. Here was the masterwork of Leonardo da Vinci, and it didn't look worth wasting a whole day on his hind legs in Paris, France.

It was the same letdown that Terry Fletcher felt after seeing that ancient petroglyph of the dancing flute player, Kokopelli, after seeing it painted on neckties and glazed on dog-food bowls. Hooked into bathmats and toilet-seat covers. When, at last, he'd gone to New Mexico and seen the original, hammered and painted into a cliff face—his first thought was: How trite . . .

All the dinky old masterpiece paintings with their puffed-up reputations, the British post-office stickers, what it meant was, he could do better. He could paint better and sneak his work into museums, framed and wrapped inside his coat. Nothing too big, but he could put double-sided mounting tape on the back, and when the right moment came . . . just stick the painting on the wall. Right there for the world to see, between the Rubens and the Picasso . . . an original work by Terry Fletcher.

In the Tate Gallery, crowding the Turner painting of Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps, there would be Terry's mom, smiling. She'd be drying her hands in a red-and-white-striped dishtowel. In the Prado Museum, butted up against the Velázquez portrait of the Infanta would be his girlfriend, Rudy. Or his dog, Boner.

Sure, it was his work, his signature, but this would be about heaping glory on the people he loved.

It's too bad that most of his work would end up hung in a museum's bathroom. It was the only space without a guard or security camera. During slow hours, he could even step into the ladies' room and hang a picture.

Not every tourist went into every gallery of a museum, but they all went to the bathroom.

It almost didn't seem to matter, how the picture looked. What made it art, a masterpiece, that seemed to depend on where it hung . . . how rich the frame looked . . . and what other work it hung beside. If he did his research, found the right antique frame, and hung his picture in the center of a crowded wall, it would be there for days, maybe weeks, before he got a call from the museum staff. Or the police.

Then came the charges: malicious mischief, destruction of public property, graffiti.

“Litter,” a judge called his art, and slapped Terry with a fine and a night in jail.

In the cell the police give Terry Fletcher, everybody before him had been an artist, scratching away the green paint to make pictures on each wall. Then to sign their name. Petroglyphs more original than Kokopelli. The Mona Lisa. By names that weren't Pablo Picasso. It was that night, looking at those pictures, Terry almost gave up.

Almost.

The next day, a man came to his studio, where black flies circled a pile of fruit Terry had been trying to paint when he was arrested. This was the lead art critic for a chain of newspapers. He was a friend of the judge from the night before, and this critic said, yes, he found the whole story funny as hell. A perfect story for his syndicated column about the art world. Even with the sweet smell of the rotting fruit, the flies buzzing, this man said he'd love to see Terry's work.

“Very good,” the critic said, looking at canvas after canvas, each of them small enough to fit inside a trench coat. “Very, very good.”

The black flies kept circling, landing on the spotted apples and black bananas, then buzzing around the two men.

The critic wore eyeglasses with each lens as thick as the porthole on a ship. Talking to him, you'd want to shout, the way you'd yell to someone behind an upstairs window, inside a big house and not coming to answer the locked door.

Still, he was absolutely, positively, undeniably NOT Tannity Brewster.

Most of the best pictures, Terry told him, they were still in lockup as evidence in future trials.

But the critic said that didn't matter. The day after, he brought a gallery owner and a collector, both of them famous from their opinions being in national magazines all the time. The group of them look at his work. They keep repeating the name of an artist famous for his messy prints of dead celebrities and signing his work huge with a can of red spray paint.

Again, this gallery owner was not Dennis Bradshaw. And when she spoke, this art collector had a Texan accent. Her red-blond hair was the exact creepy orange-peel color as her tanned shoulders and neck, but she was not Bret Hillary Beales.

She's a totally made-up character. But as she looked at his painting, she kept using the word “bankable.”

She even had a little tattoo that said “Sugar” in lacy script on her ankle, just above her sandaled foot, but she was in no way, absolutely not, nope, NOT Miss Bret Hillary Beales.

No, this fake, made-up critic, art collector, and gallery owner, at last, they tell our artist: Here's the deal. They have millions invested in the work of this messy printmaker, but his current output was flooding the art market. He was making money with volume, but driving down the value of his earlier work. The value of their investment.

The deal was, if Terry Fletcher will kill the printmaker—then the art critic, the gallery owner, and the collector will make Terry famous. They'll turn him into a good investment. His work will sell for a fortune. The pictures of his mother and girlfriend, his dog and hamster, they'll get the buildup they need to become as classic as the Mona Lisa. As the Kokopelli, that Hopi god of mischief.

In his studio, the black flies still circled the same heap of soft apples and limp bananas.

And if it helps, they tell Fletcher, the printmaker only got famous because he murdered a lazy sculptor, who in turn had murdered a pushy painter, who had murdered a sell-out collage maker.

All those people are still dead while their work sits in a museum, like a bank account every minute snowballing in value. And not even pretty value, as the colors go brown as a van Gogh sunflower, the paint and varnish cracking and turning yellow. Always so much smaller than people would expect after waiting all day in line.

The art market had worked this way for centuries, the critic said. If Terry chose not to take this, his first real “commission,” it was no problem. But he still had a long future of unsettled court cases, charges still outstanding against him. These art people could wipe out all that with a phone call. Or they could make it worse. Even if he did nothing, Terry Fletcher could still go to jail for a long, long time. That scratched green cell.

After that, who would believe the word of a jailbird?

So Terry Fletcher, he says: Yes.

It helps that he's never met the printmaker. The gallery owner gives him a gun and tells him to wear a nylon stocking over his head. The gun is only the size of your hand with the fingers straight but held tight together. A tool easy to hide in your palm, it's only the size of a package label, but does a job just as forever. The sloppy printmaker will be in the gallery until it closes. After that, he'll walk home.

That night, Terry Fletcher shoots him, three times—pop, pop, pop—in the back. A job faster than hanging his dog, Boner, in the Guggenheim Museum.

A month later, Fletcher has his first real show in a gallery.

This is NOT the Pell/Mell Gallery. It has the same black and pink checkerboard tiles on the floor, and a matching striped canopy over the door, and oodles of smart people go there to invest in art, but this is some other, let's-pretend kind of gallery. Filled with fake smart people.

It's after that Terry's career gets complicated. You might say he did his job too well, because the art critic sends him off to kill a conceptual artist in Germany. A performance artist in San Francisco. A kinetic sculptor in Barcelona. Everyone thinks Andy Warhol died from gallbladder surgery. You think Jean-Michel Basquiat died of a heroin overdose. That Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe died from AIDS.

The truth is . . . you think what people want you to think.

This whole time, the critic says if Fletcher backs down the art world will frame him for the first murder. Or worse.

Terry asks, What's worse?

And they don't say.

Leave it to an American to take something too far.

Between killing every sell-out artist, every lazy, sloppy artist, Terry Fletcher has no time to do his own art well. Even the pictures of Rudy and his mom, they look rushed, messy, as if he couldn't care less. More and more, he's knocking out different versions of the dancing, flute-playing Kokopelli. He's blowing up photos of the Mona Lisa to wall-sized, then hand-coloring the photos in colors popular for room decoration that year. Still, if his signature is at the bottom, people buy it. Museums buy it.