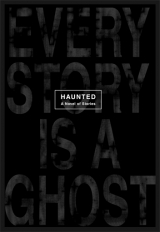

Текст книги "Haunted"

Автор книги: Charles Michael «Chuck» Palahniuk

Жанр:

Повесть

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

In the steel blade of a straight razor, the handle, chromium, scrolled and heavy—reflected there, Claire can see her future.

There, among the shaving mugs and horsehair brushes. Tall stained-glass church windows. Beaded evening bags.

Alone in the shop with Marilyn Monroe's lost child. Alone in this museum of things that no one wanted. Everything dirty with the reflection of something terrible.

Telling the story now, locked in the bathroom stall, Claire says how she picked up the razor and kept walking, down every aisle, always peeking at the blade to see if it showed her the same scene.

Telling her story now, sitting in the bathroom at the back of the antique store, Claire says it's not easy, being a gifted psychic.

The truth is, Claire's not easy to be married to. Over dinner at a restaurant, she may be listening, then her entire body will shudder. One hand will fly to cover her eyes, and her head will rear back and twist away from you. Still shaking, she'll peek out at you from between her fingers. A beat later, she'll sigh and put one hand against her mouth in a fist, biting the knuckle but looking at you without a word.

When you ask her what's wrong . . .

Claire will say, “You don't want to know. It's too awful.”

But when you press her to tell . . .

Claire will say, “Just promise me. Promise you'll stay away from all cars for the next three years . . .”

The truth is, even Claire knows she can be wrong. To test herself, she picks up a polished silver cigarette-case. And reflected there is her future: her holding the straight razor.

When it's closing time, she walks to the front of the shop, just in time to watch the old man turn the sign from “Open” to “Closed.” He was pulling down the shade that covered the window in the front door. The shop display window was cluttered with egg cups. Chenille bathrobes and bedspreads. Perfume bottles shaped like Southern belles wearing hoop skirts. Dead butterflies framed behind glass. Rusted birdcages. Railroad lanterns with shades of red or green glass. Folding silk fans. No one on the street could see inside.

The old-man cashier says, “Made up your mind?” The jar is back, locked in the glass cabinet next to his register. In the white murk, only a dark eye and the shell of a tiny ear show through.

Reflected in the jar's curved side, distorted there, while the old man had told the story of Monroe's murder, Claire had seen something else: A man tipping a small bottle between two lips. A face rolling back and forth against a pillow. The man wiping the lips with his shirtsleeve. His eyes settling on the bedside table. The phone and lamp and the jar.

In Claire's vision, the man's face comes closer. His two hands reach out, huge, until they wrap the jar in darkness.

That reflected face, it's the old-man cashier, without his wrinkles. With lots of brown hair.

Behind the counter, the jar just sits there, throbbing with energy. Glowing with power. A sacred relic trying to tell her something important. A time capsule of stories and events wasted here, locked in a glass case. More compelling than the best television series. More honest than the longest documentary. A primary history source. A real player. The child sits there, waiting for Claire to rescue it. To listen.

Wanting justice. Revenge.

Still watched by the security cameras, Claire holds up the straight razor. She says, “I want to buy this, but I don't see a price on it . . .”

And the old man leans over the counter for a closer look.

Outside the shopwindows, the street is empty. The security video monitors show the store, every aisle and corner, empty.

In the monitor, the old man falls backward, smashing the glass curio cabinet behind him, then sliding to the floor in a mess of broken glass and blood. The jar tipping, then falling, then broken.

Calling now, from a bathroom stall, Claire Upton tells her husband, “It was a doll. A plastic baby doll.”

Her purse and coat and umbrella spattered with sticky red.

On the phone, she says, “Do you know what this means?”

And again, she asks how best to destroy a video camera.

20

The Baroness Frostbite leans closer, a steaming bowl of something liquid cupped in her hand, and she says, “No carrots. No potatoes. Now, drink it.”

And, curled on her bed, in the camera spotlight, Miss America says, “No.” She looks at the rest of us crowded outside the doorway, Director Denial included, then Miss America turns away to face the concrete wall, saying, “I know what that is . . .”

The Baroness Frostbite says, “You're still bleeding.”

Leaning into the room, Director Denial says, “You need to eat something soon or you'll die.”

“Then let me die,” Miss America says, her face muffled in the pillow.

All of us in the hallway, listening. Recording. Witnesses.

The camera behind the camera behind the camera.

The Baroness Frostbite leans closer with the soup. In the rising steam of it, her mutilated lips reflected in the shimmering hot grease that floats on top, the Baroness says, “But we don't want you to die.”

Still facing the wall, Miss America says, “Since when? The rest of you, you'll only have to split the story one less way.”

“We don't want you to die,” the Reverend Godless says, from the doorway, “because we don't have a freezer.”

Miss America turns to look at the bowl of hot soup. She stares at our faces, leaned halfway into her dressing room. The teeth inside our mouths, waiting. Our tongues, swimming in drool.

Miss America says, “Freezer?”

And the Reverend Godless makes a fist and knocks on his forehead, the way you'd knock on a door, saying, “Hello?” He says, “We need you to stay alive until the rest of us are hungry again.”

Her baby was the first course. Miss America will be the main course. Dessert is anybody's guess.

The tape recorder in the Earl of Slander's hand, it's ready to tape over her last scream with her next. Agent Tattletale's camera is focused to videotape over everything so far, in order to catch our next big plot point.

Instead, Miss America asks, Is this how it will go? Her voice shrill and shaky, a bird's song. Will this be just one horrible event after another after another after another—until we're all dead?

“No,” Director Denial says. Brushing cat hair off her sleeve, she says, “Just some of us.”

And Miss America says she doesn't mean just here, in the Museum of Us. She means life. Is the whole world just people eating up other people? People attacking and destroying each other?

And Director Denial says, “I know what you meant.”

The Earl of Slander writes that down in his notepad. The rest of us, nodding.

The Mythology of Us.

Still holding the soup, looking at her own reflection in the grease on top, the Baroness Frostbite says, “I used to work in a restaurant, in the mountains.” She dips a spoon into the bowl and brings it steaming toward Miss America's face.

“Eat,” the Baroness says. “And I'll tell you how I lost my lips . . .”

Absolution

A Poem About the Baroness Frostbite

“Even if God won't forgive us,” says the Baroness Frostbite, “we can still forgive Him.”

We should show ourselves to be bigger than God.

The Baroness onstage, she tells most people, “Gum disease,”

when they look too long at what's left

of her face.

Her lips are only the ragged edge of her skin,

greased red with lipstick.

Her teeth, inside:

the yellow ghost of every cup of coffee,

and every cigarette in her middle-aged life.

Onstage, instead of a spotlight, a movie fragment:

The shifting, falling color of snow flurries.

No two of the tiny blue shadows the same shape or size.

The rest of her is goosedowned, quilted and insulated,

her hair tucked under a knitted hat,

but never again

warm enough.

Standing center stage, the Baroness Frostbite says, “We should forgive God . . .”

For making us too short. Fat. Poor.

We should forgive God our baldness.

Our cystic fibrosis. Our juvenile leukemia.

We should forgive God's indifference, His leaving us behind:

Us, God's forgotten Science Fair project, left to grow mold.

God's goldfish, ignored until we're forced to eat our own shit off the bottom.

Her hands inside mittens, the Baroness points to her face, saying, “People . . .”

They assume she was once gorgeously beautiful.

Because now she looks so—bad.

People, they need some sense of justice. A balancing act.

They assume cancer, her own fault, something she deserved.

A disaster she made happen herself.

So she tells them, “Floss. For God's sake, floss before bed every night.”

And every night the Baroness, she forgives other people.

She forgives herself.

And she forgives God for those disasters that just seem to

happen.

Hot Potting

A Story by the Baroness Frostbite

“Come February nights,” Miss Leroy used to say, “and every drunk driver was a blessing.”

Every couple looking for a second honeymoon to patch up their marriage. People falling asleep at the steering wheel. Anybody who pulled off the highway for a drink, they were somebody Miss Leroy could maybe talk into renting a room. It was half her business, talking. To keep people buying another next drink, and another, until they had to stay.

Sometimes, sure, you're trapped. Other times, Miss Leroy would say, you just sit down for what turns out to be the rest of your life.

Rooms there at the Lodge, most people, they expect better. The iron bed frames teeter, the rails and footboards worn where they notch together. The nuts and bolts, loose. Upstairs, every mattress is lumpy as foothills, and the pillows are flat. The sheets are clean, but the well water up here, it's hard. You wash anything in this water, and the fabric feels sandpaper-rough with minerals and smells of sulfur.

The final insult is, you have to share a bathroom down the hall. Most folks don't travel with a bathrobe, and this means getting dressed just to take a leak. In the morning, you wake up to a stinking sulfur bath in a white-cold cast-iron claw-foot tub.

It's a pleasure for her to herd these February strangers toward the cliff. First, she shuts off the music. A full hour before she even starts talking, she turns down the volume, a notch every ten minutes, until Glen Campbell is gone. After traffic turns to nothing going by on the road outside, she turns down the heat. One by one, she pulls the string that snaps off each neon beer sign in the window. If there's been a fire in the fireplace, Miss Leroy will let it burn out.

All this time, she's herding, asking what plans these people have. February on the White River, there's less than nothing to do. Snowshoe, maybe. Cross-country ski, if you bring your own. Miss Leroy lets some guest bring up the idea. Everybody gets around to this same suggestion.

And if they don't, then she brings up the notion of hot potting.

Her stations of the cross. She walks her audience through the road map of her story. First she shows herself, how she looked most of her life ago, twenty years old and out of college for the summer, car camping up the White River, begging for a summer job, what back then was the dream job: tending bar here at the Lodge.

It's hard to imagine Miss Leroy skinny. Her skinny with white teeth, before her gums started to pull back. Before the way they look now, the brown root of each tooth exposed, the way carrots will crowd each other out of the ground if you plant the seed too close together. It's hard to imagine her voting Democrat. Even liking other people. Miss Leroy without the dark shadow of hair across her top lip. It's hard to imagine college boys waiting an hour in line to fuck her.

It makes her seem honest, saying something funny and sad like that, about herself.

It makes people listen.

If you hugged her now, Miss Leroy says, all you'd feel is the pointy wire of her bra.

Hot potting, she says, is, you get a gang of kids together and hike up the fault side of the White River. You pack in your own beer and whiskey and find a hot-springs pool. Most pools stand between 150 and 200 degrees, year-round. Up at this elevation, water boils at 198 degrees Fahrenheit. Even in winter, at the bottom of a deep icy pit, the side of snowdrifts sloping into them, these pools are hot enough to boil you alive.

No, the danger wasn't bears, not here. You wouldn't see wolves or coyote or bobcat. Downriver, yes, just one click away on your odometer, just one radio song down the highway, the motels had to chain their garbage cans shut. Down there, the snow was busy with paw prints. The night was noisy with packs howling at the moon. But here, the snow was smooth. Even the full moon was quiet.

Upriver from the Lodge, all you had to worry about was being scalded to death. City kids, dropped out of college, some stay around a couple years. Some way, they pass down the okay about which pools are safe and where to find them. Where not to walk, there's only a thin crust of calcium or limestone sinter that looks like bedrock but will drop you through to deep-fry in a hidden thermal vent.

The scare stories, they pass along also. A hundred years back, a Mrs. Lester Bannock, here visiting from Crystal Falls, Pennsylvania, she stopped to wipe the steam from her smoked glasses. The breeze shifted, blowing hot steam in her eyes. One wrong step, and she was off the path. Another wrong step, and she lost her balance, landing backward, sitting in water scalding hot. Trying to stand, she pitched forward, landing facedown in the water. Screaming, she was hauled out by strangers.

The sheriff who raced her into town, he requisitioned every drop of olive oil from the kitchen at the Lodge. Coated in oil and wrapped in clean sheets, she died in a hospital, still screaming, three days later.

Recent as three summers ago, a kid from Pinson City, Wyoming, he parked his pickup truck and out jumped his German shepherd. The dog splashed dead center, jumping into a pool, and yelped itself to death mid–dog paddle. The tourists chewing their knuckles, they told the kid, don't, but he dove in.

He surfaced just once, his eyes boiled white and staring. Rolling around blind. No one could touch him long enough to grab hold, and then he was gone.

The rest of that year, they dipped him out with nets, the way you'd clean leaves and dead bugs out of a swimming pool. The way you'd skim the fat off a pot of stew.

At the Lodge bar, Miss Leroy would pause to let people see this a moment in their heads. The bits of him left all summer skittering around in the hot water, a batch of fritters spitting to a light brown.

Miss Leroy would smoke her cigarette.

Then, like this is something she's just remembered, she'd say, “Olson Read.” And she'd laugh. Like this is something she doesn't think about part of every minute, every hour she's awake, Miss Leroy will say, “You should've met Olson Read.”

Big, fat, virtuous, sin-free Olson Read.

Olson was a cook at the Lodge, fat and pale white, his lips too big, blown up with blood and squirming red as sushi against the sticky-rice-white skin of his face. He watched those hot pools. The way he'd kneel beside them all day, watching it, the bubbling brown froth, hot as acid.

One wrong step. One quick slide down the wrong side of a snowdrift, and just hot water would do to you what Olson did to food.

Poached salmon. Stewed chicken and dumplings. Hard-boiled eggs.

In the Lodge kitchen, Olson used to sing hymns so loud you could hear them in the dining room. Olson, huge in his flapping white apron, the ties knotted and cutting into his thick, deep waist, he sat in the bar, reading his Bible in the almost-dark. The beer-and-smoke smell of the dark-red carpet. If he joined your table in the staff break room, Olson bowed his head to his chest and said a rambling blessing over his baloney sandwich.

His favorite verb was “fellowship.”

A night when Olson walked into the pantry and found Miss Leroy kissing a bellhop, just some liberal-arts dropout from NYU, Olson Read told them kissing was the devil's first step to fornication. With his rubbery red lips, Olson told everyone he was saving himself for marriage, but the truth was, he couldn't give himself away.

To Olson, the White River was his Garden of Eden, the proof his God did beautiful work.

Olson watched the hot springs, the geysers and steaming mud pots, the way every Christian loves the idea of hell. The way every Eden had to have its snake. He watched the scalding water steam and spit, the same way he'd peek through the order window and watch the waitresses in the dining room.

On his day off, he'd carry his Bible through the woods, through the clouds and fog of sulfur. He'd be singing “Amazing Grace” or “Nearer My God to Thee,” but only the fifth or sixth verses, the parts so strange and unknown you might think he made them up. Walking on the sinter, the thin crust of calcium that forms the way ice sets up on water, Olson would step off the boardwalk and kneel at the deep edge of a spitting, stinking pool. Kneeling there, he'd pray out loud for Miss Leroy and the bellhop. He'd pray to his Lord, our God Almighty, Maker of Heaven and Earth. He'd pray for the immortal soul of each busboy by name. He'd inventory the sins of each hotel maid out loud. Olson's voice rising with the steam, he prayed for Nola, who pinned up the hem of her skirt too high and committed the act of oral sex with any hotel guest willing to cut loose a twenty-dollar bill. The tourist families standing back, safe on the boardwalk behind him, Olson begged mercy for the dining-room waiters, Evan and Leo, who assaulted each other with lewd acts of sodomy every night in the men's dorm. Olson wept and shouted about Dewey and Buddy, who breathed glue from a brown paper bag while they washed the dishes.

There at the gates of his hell, Olson yelled opinions into the trees and sky. Making his report to God, Olson walked out after the dinner shift and shouted your sins at the stars so bright they bled together in the night. He begged for God's mercy on your behalf.

No, nobody very much liked Olson Read. Nobody any age likes a tattletale.

They'd all heard the stories about the woman wrapped in olive oil. The kid cooked to soup with his dog. And Olson especially would listen, his eyes bright as candy. This was proof of everything he held dear. The truth of this. Proof you can't hide what you've done from God. You can't fix it. We'd be awake and alive in Hell, but hurting so bad we'd wish we could die. We'd spend all eternity suffering, someplace no one in the world would trade us to be.

Here, it would be, Miss Leroy would stop talking. She'd light a new cigarette. She'd draw you another beer.

Some stories, she'd say, the more you tell them, the faster you use them up. Those kind, the drama burns off, and every version, they sound more silly and flat. The other kind of story, it uses you up. The more you tell it, the stronger it gets. Those kind of stories only remind you how stupid you were. Are. Will always be.

Telling some stories, Miss Leroy says, is committing suicide.

It's here that she'd work hard to make the story boring, saying how water heated to 158 degrees Fahrenheit causes a third-degree burn in one second.

The typical thermal feature along the White River Fault is a vent that opens to a pool crusted around the edge with a layer of that crystallized mineral. The average temperature of thermal features along the White River being 205 degrees Fahrenheit.

One second in water this hot, and pulling your socks off will pull off your feet. The cooked skin of your hands will stick to anything you touch and stay behind, perfect as a pair of leather gloves.

Your body tries to save itself by shifting fluid to the burn, to dissipate the heat. You sweat, dehydrating faster than the worst case of diarrhea. Losing so much fluid your blood pressure drops. You go into shock. Your vital organs shut down in rapid succession.

Burns can be first-degree, second-, third-, or fourth-degree. They can be superficial, partial-thickness, or full-thickness burns. In superficial or first-degree burns, the skin turns red without blistering. Think of a sunburn and the subsequent desquamation of necrotic tissue—the dead, peeling skin. In full-thickness, third-degree burns, you get the dry, white leather look of a knuckle that bumps the top heating element when you take a cake out of the oven. In fourth-degree burns, you're cooked worse than skin deep.

To determine the extent of a burn, the medical examiner will use the “Rule of Nines.” The head is 9 percent of the body's total skin. Each arm is 9 percent. Each leg is 18 percent. The torso front and back are each 18 percent. One percent for the neck, and you get the whole 100 percent.

Swallowing even a mouthful of water this hot causes massive edema of the larynx and asphyxial death. Your throat swells shut, and you choke to death.

It's poetry to hear Miss Leroy spin this out. Skeletonization. Skin slippage. Hypokalemia. Long words that take everybody in the bar to safe abstracts, far, far away. It's a nice little break in her story, before facing the worst.

You can spend your whole life building a wall of facts between you and anything real.

A February just like this, most of her life ago, Miss Leroy and Olson, the cook, were the only people in the Lodge that night. The day before dropped three feet of new snow, and the plows hadn't come through yet.

The same as every night, Olson Read takes his Bible in one fat hand and goes tramping off into the snow. Back then, they had coyotes to worry about. Cougar and bobcat. Singing “Amazing Grace” for a mile, never repeating a verse, Olson tramps off, white against the white snow.

The two lanes of Highway 17, lost under snow. The neon sign saying The Lodge in green neon, free-standing on a steel pole anchored in concrete with a low brick planter around the base of it. The outside world, like every night, is moonlight black and blue, the forest just dark pine-tree shapes stretched up.

Young and thin, Miss Leroy never gave Olson Read a second thought. Never realized how long he was gone until she heard the wolves start to howl. She was looking at her teeth, holding a polished butter knife so she could see how straight and white her teeth looked. She was used to hearing Olson shout each night. His voice shouting her name followed by a sin, real or imagined, it came from the woods. She smoked cigarettes, Olson shouted. She slow-danced. Olson screamed at God on her behalf.

Telling the story now, she'll make you tweeze the rest out of her. The idea of her trapped here. Her soul in limbo. Nobody comes to the Lodge planning to stay the rest of their life. Hell, Miss Leroy says, there's things you see happen worse than getting killed.

There's things that happen, worse than a car accident, that leave you stranded. Worse than breaking an axle. When you're young. And you're left tending bar in some little noplace for the rest of your life.

More than half her life ago, Miss Leroy hears the wolves howl. The coyotes yip. She hears Olson screaming, not her name or any sin, but just screaming. She goes to the dining-room side door. She steps outside, leaning out over the snow, and turns her head sideways to listen.

She smells Olson before she can see him. It's the smell of breakfast, of bacon frying in the cold air. The smell of bacon or Spam, sliced thick and hissing crisp in its own hot fat.

At this point in her story, the electric wall heater always comes on. That moment, the moment the room's got as cold as it can get. Miss Leroy knows that moment, can feel it make the hair stand up on her top lip. She knows when to stop a second. To leave a little way of quiet, and then—voom—the rush and wail of warm air out of the heater. The fan makes a low moan, far away at first, then up-close loud. Miss Leroy makes sure the barroom's dark by now. The heater comes on, the low moan of it, and people look up. All they can see in the window is their own reflection. Their own face not recognized. Looking inside at them is a pale mask full of dark holes. The mouth is a hanging-open dark hole. Their own eyes, two close-together staring black holes through to the night behind them.

The cars parked just outside, they look a hundred cold miles away. Even the parking lot looks too far to walk in this kind of dark.

The face of Olson Read, when she found him, his neck and head, this last 10 percent of him was still perfect. Beautiful even, compared to the peeling, boiled-food rest of his body.

Still screaming. As if the stars give a shit. This something left of Olson, dragging itself down this side of the White River, it stumbled, knees wobbly, staggering and coming apart.

There were parts of Olson already gone. His legs, below his knees, cooked and drug off over the broken ice. Bit and pulled off, the skin first and then the bones, the blood so cooked inside there's nothing going off behind him but a trail of his own grease. His heat melting deep in the snow.

The kid from Pinson City, Wyoming, the kid who jumped in to save his dog. Folks say that when the crowd pulled him out his arms popped apart, joint by joint, but he was still alive. His scalp peeled back off his white skull, but he was still awake.

The surface of the seething water, it spit hot and sparkling rainbow colors from the kid's rendered fat, the grease of him floating on the surface.

The kid's dog boiled down to a perfect dog-shaped fur coat, its bones already cooked clean and settling into the deep geothermal center of the world, the kid's last words were, “I fucked up. I can't fix this. Can I?”

That's how Miss Leroy found Olson Read that night. But worse.

The snow behind him, the fresh powder all around him, it was cut with drool.

All around his screams, fanned out around behind him, Miss Leroy could see a swarm of yellow eyes. The snow stamped down to ice in the prints of coyote feet. The four-toe prints of wolf paws. Floating around him were the long skull faces of wild dogs. Panting behind their own white breath, their black lips curled up along the ridge of each snout. Their little-root teeth meshed together, tight, tugging back on the rags of Olson's white pants, the shredded pant legs still steaming from what's boiled alive inside.

The next heartbeat, the yellow eyes are gone and what's left of Olson is what's left. Snow kicked up by back feet, it still sparkles in the air.

The two of them, in the warm cloud of bacon smell, Olson pulsed with heat, a big baked potato sinking deeper into the snow beside her. His skin was crusted now, puckered and rough as fried chicken, but loose and slippery on top of the muscle underneath, the muscle twisting, cooked, around the core of warm bone.

His hands clamped tight around her, around Miss Leroy's fingers, when she tried to pull away, his skin tore. His cooked hands stuck, the way your lips freeze to the flagpole on the playground in cold weather. When she tried to pull away, his fingers split to the bone, baked and bloodless inside, and he screamed and gripped Miss Leroy tight.

He was too heavy to move. Sunk there in the snow.

She was anchored there, the side door to the dining room only twenty footprints away in the snow. The door was still open, and the tables inside set for the next meal. Miss Leroy could see the dining room's big stone mountain of a fireplace, the logs burning inside. She could watch, but it was too far away to feel. She swam with her feet, kicking, trying to drag Olson, but the snow was too deep.

Instead of moving, she stayed, hoping he would die. Praying to God to kill Olson Read before she froze. The wolves watching with their yellow eyes from the dark edge of the forest. The pine-tree shapes going up into the night sky. The stars above them, bleeding together.

That night, Read Olson told her a story. His own private ghost story.

When we die, these are the stories still on our lips. The stories we'll only tell strangers, someplace private in the padded cell of midnight. These important stories, we rehearse them for years in our head but never tell. These stories are ghosts, bringing people back from the dead. Just for a moment. For a visit. Every story is a ghost. This story is Olson's.

Melting snow in her mouth, Miss Leroy spit the water into Olson's fat red lips, his face the only part of him that she could touch without getting stuck. Kneeling there beside him. The devil's first step to fornication. That kiss, the moment Olson had saved himself for.

For most of her life, she never told anyone what he yelled. Holding this inside was such a burden. Now she tells everyone, and it's no better.

That boiled, sad thing up the White River, it screamed, “Why did you do this?”

It screamed, “What did I do?”

“Timber wolves,” Miss Leroy says, and she laughs. We don't have that trouble. Not here, she says. Not anymore.

How Olson died, it's called myoglobulinaria. In extensive burns, the burned muscles release the protein myoglobulin. This flood of protein into the bloodstream overwhelms each kidney. The kidneys shut down, and the body fills with fluid and blood toxins. Renal failure. Myoglobulinaria. When Miss Leroy says these words, she could be a magician doing a trick. They could be a spell. An incantation.

This way to die takes all night.

The next morning, the snow plow came through. The driver found them: Olson Read dead and Miss Leroy asleep. From melting snow in her mouth all night, her gums were patched with white. Frostbite. Read's dead hands were still locked around hers, protecting her fingers, warm as a pair of gloves. For weeks, the frozen skin around the base of each tooth, it peeled away, soft and gray from the brown root, until her teeth looked the way they do. Until her lips were gone.

Desquamating necrotic tissue. Another magic spell.

There's nothing out in the woods, Miss Leroy would tell people. Nothing evil. It's just something so sad and alone. It's Olson Read not knowing, still, what he did wrong. Not knowing where he's at. So terrible and alone, even the wolves, the coyotes are gone from up that end of the White River.

That's how a scary story works. It echoes some ancient fear. It re-creates some forgotten terror. Something we'd like to think we've grown beyond. But it can still scare us to tears. It's something you'd hoped was healed.