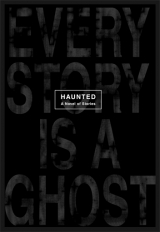

Текст книги "Haunted"

Автор книги: Charles Michael «Chuck» Palahniuk

Жанр:

Повесть

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Until he pretended to meet her by accident, at church again.

There, Steed said they were finished—because she was too slutty. Almost a whore.

“I swear,” the Matchmaker says, “he called her a whore. The nerve of that guy . . .”

God bless him.

All of this, the Matchmaker's secret plan to give his girlfriend

a premature, accelerated broken heart. Then catch her on the rebound.

His last meeting with Steed, he paid an extra fifty bucks for a blow job.

Steed kneeling there, at work between his knees.

This way, when his future wife had her well-researched, multiple orgasms,

the man in her head would not be a total stranger to her husband,

the Matchmaker.

Ritual

A Story by the Matchmaker

There's a joke the uncles only tell when they're drunk.

Half the joke is the noise they make. It's the sound of someone hawking up spit from the back of his throat. A long, rasping sound. After every family event, when there's nothing left to do except drink, the uncles will take their chairs out under the trees. Out where we can't see them in the dark.

While the aunts wash dishes, and the cousins run wild, the uncles are out back in the orchard, tipping bottles back, leaning back on the two rear legs of their chairs. In the dark, you can hear one uncle make the sound: Shooo-rook. Even in the dark, you know he's pulled one hand sideways through the air in front of him. Shooo-rook, and the rest of the uncles laugh.

The aunts hear the sound and it makes them smile and shake their heads: Men. The aunts don't know the joke, but they know anything that makes men laugh so hard must be stupid.

The cousins don't know the joke, but they make the sound. Shooo-rook. They pull a hand through the air, sideways, and fall down laughing. Their whole childhood, all the kids did it. Said: Shooo-rook. Screamed it. The family's magic formula to make each other laugh.

The uncles would lean down to teach them. Even as little kids, barely on two legs, they'd mimic the sound. Shooo-rook. And the uncles would show how to pull one hand sideways, always from left to right, in front of your neck.

They'd ask—the cousins, hanging off the arm of an uncle, kicking their feet in the air—they'd ask, what did the sound mean? And the hand motion?

It was an old, old story an uncle might tell them. The sound was from when the uncles were all young men in the army. During the war. The cousins would climb the pockets of an uncle's coat, a foot hooked in one pocket, a hand reaching for the next pocket higher up. The way you'd climb trees.

And they'd beg: Tell us. Tell us the story.

But all an uncle would do is promise: Later. When they were grown up. The uncle would catch you under the arms and throw you over his shoulder. He'd carry a cousin that way, running, racing the other uncles into the house, to kiss the aunts and eat another slice of pie. You'd pop popcorn and listen to the radio.

It was the family password. A secret most of them didn't understand. A ritual to keep them safe. All the cousins knew was, it made them laugh together. This was something only they knew.

The uncles said the sound was proof that your worst fears might just disappear. No matter how terrible something looked, it might not be around tomorrow. If a cow died, and the other cattle looked sick, swelling with bloat and about to die, if nothing could be done, the uncles made the sound. Shooo-rook. If the peaches were setting in the orchard and a frost was predicted that night, the uncles said it. Shooo-rook. It meant the terror you were helpless to stop, it might just stop itself.

Every time the family got together, it was their greeting: Shooo-rook. It made the aunts cross-eyed, all these cousins making that silly sound. Shooo-rook. All the cousins waving one hand through the air. Shooo-rook. The uncles laughing so hard they stood leaning forward with one hand braced on each knee. Shooo-rook.

An aunt, someone married into the family, she might ask: What did it mean? What was the story behind it? But the uncles would shake their heads. The one uncle, her own husband, would slip his arm around her waist and kiss her cheek and tell her, honey bunch, she didn't want to know.

The summer I turned eighteen, an uncle said it to me, alone. And that time, he didn't laugh.

I'd been drafted to serve in the army, and no one could know if I'd ever come back.

There wasn't a war, but there was cholera in the army. There was always disease and accidents. They were packing a bag for me to take, just me and the uncle, and my uncle said it: Shooo-rook. Just remember, he said, no matter how black the future looks, all your troubles could be disappeared tomorrow.

Packing that bag, I asked him. What did it mean?

It was from the last big war, he said. When the uncles were all in the same regiment. They were captured and forced to work in a camp. There, an officer from the other army would force them to work at gunpoint. Every day, they expected this man to kill them, and there was nothing they could do. Every week, trains would arrive filled with prisoners from occupied countries: soldiers and Gypsies. Most of them went from the train, two hundred steps to die. The uncles hauled away their bodies. The officer they hated, he led the firing squad.

The uncle telling this story, he said every day the uncles stepped forward to drag the dead people way—the holes in their clothes still leaking warm blood—the firing squad would be waiting for the next batch of prisoners to execute. Every time the uncles stepped in front of those guns, they expected the officer to open fire.

Then, one day, the uncle says: Shooo-rook.

It happened, the way Fate happens.

The officer, if he saw a Gypsy woman he liked, he'd take her out of line. After that batch was dead, while the uncles hauled away the bodies, the officer would make this woman undress. Standing there in his uniform, crawling with gold braid in the bright sun, surrounded by guns, the officer made the Gypsy woman kneel in the dirt and open his zipper. He made her open her mouth.

The uncles, they'd seen this happen too many times to remember. The Gypsy would bury her lips in the front of the officer's pants. Her eyes closed, she'd suck and suck and not see him take a knife from the back of his belt.

The moment the officer came to orgasm he'd grab the Gypsy by her hair, holding her head tight with one hand. His other hand would cut her throat.

It was always the same sound: Shooo-rook. His seed still erupting, he'd push her naked body away before the blood could explode from her neck.

It was a sound that would always mean the end. Fate. A sound they'd never be able to escape. To forget.

Until, one day, the officer took a Gypsy and had her kneel naked in the dirt. With the firing squad watching, the uncles watching with their feet buried in the layer of dead bodies, the officer made the Gypsy open his zipper. The woman closed her eyes and opened her mouth.

This was something the uncles had witnessed so often they could watch without seeing it.

The officer gripped the Gypsy's long hair, wrapped it in his fist. The knife flashed, and there was the sound. That sound. Now the family's secret code for laughter. Their greeting to each other. The Gypsy fell back, blood exploding from under her chin. She coughed once, and something landed in the dirt next to where she died.

They all looked, the firing squad and the uncles and the officer, and there in the dirt was half a cock. Shooo-rook, and the officer had cut off his own erection stuck down the throat of this dead woman. The zipper in the officer's pants was still erupting with his seed, exploding with blood. The officer reached one hand to where his cock lay coated with dirt. His knees buckled.

Then the uncles were dragging away his body to bury it. The next officer in charge of the camp, he wasn't so bad. Then the war was over, and the uncles came home. Without what happened, their family might not be. If that officer had lived, I might not exist.

That sound, their secret family code, the uncle told me. The sound means: Yes, terrible things happen, but sometimes those terrible things—they save you.

Outside the window, in the peach trees back of their house, the other cousins run. The aunts sit on the front porch, shelling peas. The uncles stand, their arms folded, arguing about the best way to paint a fence.

You might go to war, the uncle says. Or you might get cholera and die. Or, he says, and moves one hand sideways, left to right, in the air below his belt buckle: Shooo-rook . . .

12

It's Sister Vigilante who finds the body. She's coming down the lobby stairs, from the first-balcony foyer, from turning on the lights in the projection booth, when she stumbles over Miss America's pink exercise wheel gripped between two dead-white hands.

There, in the video camera's little viewing screen, the Duke of Vandals's stretched out at the foot of the lobby stairs, his fringed buckskin shirttails hanging out, his blond hair fanned out, facedown on the blue carpet. The pink plastic wheel is between his hands. One side of his face is stomped flat, the hair pasted down in every direction with blood.

The royalties to our story split one less way.

Sister Vigilante, she had the video camera. Getting around in the dark, Mr. Whittier had used a flashlight, but now the old batteries were as dead as him and Lady Baglady. Now Sister Vigilante used the camera spotlight, with its rechargeable batteries, to find her way up and down the stairs before dawn, and after dark.

“Subarachnoid hemorrhage,” Sister Vigilante says, her words recorded as she pans the camera over the body. “With partial avulsion of the left cerebellar hemisphere.” Saying, It's the most common sequela of massive head trauma. She zooms in for a close-up of the compound skull fracture, the bleeding inside the outer layers of the brain.

“As you press the skull in one spot,” she says, “the contents swell around that location and burst the skull in a rough circle.”

The camera roving over the sharp edges and dried red on the skull, Sister Vigilante's voice says, “The outbending is extensive . . .”

The camera comes up to show the rest of us, staggering into the lobby, yawning and squinting into the spotlight.

Mrs. Clark looks down at the sprawled buckskin body of the Duke, his cud of nicotine gum—plus all his teeth—knocked halfway across the lobby floor. And her inflated lips squeak out a little scream.

Miss America says, “The bastard.” She steps over to the body and kneels to pry the stiff, dead fingers off the black rubber grips of the exercise wheel. “He was trying to lose more weight than the rest of us,” she says. “The evil shit was doing aerobics to look . . . worse.”

As Miss America wrestles and kicks at the stiff fingers, Mrs. Clark says, “Rigor mortis.”

As Miss America pulls the body to one side, twisting the wheel to free it from the hands, as she pulls, the body turns faceup. The Duke of Vandals, his face is dark as a sunburn, but purple except for the tip of his nose. The tips of his chin and nose and the flat of his forehead are all blue-white.

“Livor mortis,” Mrs. Clark says. The blood settles to the lowest points of the body. Except where the face pressed into the carpet: at those points the weight of the body kept the capillaries collapsed, so no blood could pool inside.

From behind the video camera, Sister Vigilante says, “You sure seem to know a lot about dead bodies . . .”

And Mrs. Clark says, “Just what did you mean by partial avulsion of the left cerebellar hemisphere?”

The video camera still panning the body, taping over the death of Mr. Whittier, the voice of Sister Vigilante says, “That means the brains are leaking out.”

The pink wheel slips free from the Duke's hands, and the fingers seem to relax. Rigor mortis only goes away, Mrs. Clark says, as the body starts to decompose.

By now, Agent Tattletale has arrived, looking strange with both his eyes showing. Reverend Godless stands over the body. Mother Nature with her patchouli smell. The Matchmaker, his back teeth chewing around and round on a cheekful of spit and tobacco, he leans over for a better look.

The Matchmaker says, “Decomposition?”

And Mrs. Clark nods, frowning her silicone lips. After death, she says, the actin and myosin filaments of the muscles become complexed from the lack of adenosine-triphosphate production . . . She says, “You wouldn't understand.”

“Too bad,” Chef Assassin says. “If he wasn't so far gone, we might've had a big breakfast.”

Mother Nature says, “You're kidding.”

And the chef says, “No. Actually, I'm not.”

The Matchmaker is pop-eyed, squatting next to the body, digging in the back pants pocket.

Rubbing her hennaed hands together and yawning, Mother Nature says, “How can you be so awake?”

And, opening his mouth, wide, pointing a finger at the brown mess inside, the Matchmaker says, “Chaw . . .” He pulls out the wallet, slips out the paper money, and tucks the wallet back into the pocket, saying, “Kiss me, and you'll perk up, too.”

And, shaking her head, Mother Nature says, “No. Thanks.”

“Little girl,” the Matchmaker says. He spits a brown stream on the blue carpet, and he says, “you need to be a little sexier character, or no bankable actress is going to want to play you . . .”

And Saint Gut-Free pulls her away.

Sister Vigilante shuts off the camera and hands it back to Agent Tattletale.

To nobody. Or to everybody, Mrs. Clark says, “Who do you suspect?”

And Agent Tattletale says, “You.”

Mrs. Clark. She got up late last night. She found the Duke of Vandals alone, doing this stomach exercise. She crushed his skull. End of official story.

“You ever wonder,” Mrs. Clark says, “what you'll do after you sell your old life?”

And the Matchmaker licks the spit off his lips, saying, “What do you mean?” He hooks both thumbs behind the straps of his bib overalls.

“After you've sold this story,” Mrs. Clark says, “will you just look for a new villain?” She says, “For the rest of your life, will you be looking for someone new to blame everything on?”

And Agent Tattletale smiles, saying, “Relax. There's no point blaming one of us for this. There are victims,” he says, pointing a finger at his chest. “And there are villains,” he says, pointing a finger at her. “Don't create shades of gray that a mass audience can't follow.”

And Mrs. Clark says, “I did not kill this young man.”

And the Agent shrugs. He shoulders his camera, saying, “You want audience sympathy at this point, you're going to have to campaign for it.” His spotlight flickers bright, spotlighting her, and Agent Tattletale says, “Tell us one thing. Give us one good flashback to make the folks at home feel just a teeny bit sorry for you . . .”

The Nightmare Box

A Story by Mrs. Clark

The night before she disappeared, Cassandra cut off her eyelashes.

Easy as homework, Cassandra Clark takes a little pair of scissors out of her purse, little chrome fingernail-scissors, she leans into the big mirror above the bathroom sink and looks at herself. Her eyes half closed, and her mouth hanging open the way she puts on mascara, Cassandra braces one hand against the bathroom counter and uses the scissors to snip. Each long black lash falling, settling, fluttering down the sink drain, she doesn't even look at her mother reflected there, standing behind her in the mirror.

That night, Mrs. Clark hears her slip out of bed while it's still dark. In the one hour when there's no traffic in the street, she goes naked to the living room with all the lights off. There's the rumble of springs inside the old sofa. There's the rasp and—click—of a cigarette lighter. Then a sigh. A whiff of cigarette smoke.

After the sun's up, Cassandra's still there, sitting naked on the sofa with the curtains open and cars going past. All her arms and legs bunched tight around her in the cold air. In one hand, she's got the cigarette, burned down to the filter. Ashes on the sofa cushion beside her. She's awake and looking at the blank television screen. Maybe looking at herself reflected there, naked in the black glass. Her hair looks lumpy with tangles from not combing. Her lipstick from two days ago, it's still smeared across her cheek. Her eye shadow outlines the wrinkles around each eye. Her eyelashes gone, her green eyes looking dull and fake because you never see her blink.

Her mother says, “Did you dream about it?”

Mrs. Clark asks: does she want French toast? Mrs. Clark turns on the wall heater and gets Cassandra's robe off the back of the bathroom door.

Cassandra hugging herself in the cold sunshine, sitting knees-together, her breasts are pushed up by her arms. Flakes of gray cigarette ash are scattered on the top of each thigh. Flakes of gray ash settle into her pubic hair. Her feet twitch with tendons under the skin. Her feet flat and side by side on the polished wood floor, they're the only part of her not statue-still.

Mrs. Clark says, “Did you remember something?” Her mother says, “You had on your new black dress . . .” She says, “The short-short one.”

Mrs. Clark goes to put the bathrobe around her daughter, tucking it up tight around her neck. She says, “It happened in that gallery. Across from the antique store.”

Cassandra doesn't look away from her own dark reflection in the off television. She doesn't blink, and the bathrobe slips down, putting both her breasts back out in the cold.

And her mother says, what did she see?

“I don't know,” Cassandra says. She says, “I can't say.”

“Let me get my notes,” Mrs. Clark tells her. She says, “I think I have this figured out.”

It's when she comes back from the bedroom, her thick brown folder of notes in one hand, the folder open so she can pick through it with her other hand, when she looks around the living room, Cassandra's gone.

At that moment, Mrs. Clark's saying, “The way the Nightmare Box works is, the front . . .”

But Cassandra's not in the kitchen or the bathroom. Cassandra's not in the basement. That's their whole house. She's not out in the backyard or on the stairs. Her bathrobe is still on the sofa. Her purse and shoes and coat, none of them are gone. Her suitcase is still on her bed, half packed. Only Cassandra's gone.

At first, Cassandra said it was nothing. According to the notes, it was an art-gallery opening.

There in Mrs. Clark's notes, it says, “Random Interval Timer . . .”

Her notes say, “The man hung himself . . .”

It started on the night all the galleries open their new shows, and downtown was crowded with people, everyone still dressed up from the office or school and holding hands. Medium-young couples in dark clothes that wouldn't show the dirt from a taxi seat. Wearing the good jewelry they couldn't wear on the subway. Their teeth white, as if they never used teeth for anything except to smile.

They were all watching each other look at art before watching each other eat dinner.

It's all in Mrs. Clark's notes.

Cassandra had on her new black dress. The short-short one.

That night, she wanted a long glass of white wine, just to hold it. She didn't dare lift the glass, because her dress was strapless, so she kept her arms down at each side, holding her elbows close in. This flexed some muscle across her chest. Some new muscle she'd found playing basketball in school. It pushed her breasts so high her cleavage seemed to start at her throat.

That dress, it was black and stitched with black sequins and beads. It was a crust of rough black glitter with her breasts pink and meaty inside. A hard black shell.

Both her hands, the way her painted fingernails meshed together, they looked handcuffed around the stem of her wineglass. Her hair coiled and pinned up high, it was so heavy and thick. Strands and curls were coming undone, dangling, but she didn't dare reach up to fix it. Her bare shoulders, her hair coming apart, her high heels clenched the muscles of each leg, pushed her ass up, curving it out at the bottom of a long zipper.

Her perfect lipstick mouth. No red smeared on the glass she didn't dare lift. Her eyes looking huge under long eyelashes. Her green eyes the only part of her moving in the crowded room.

Standing and smiling in the center of an art gallery, she was the only woman you'd remember. Cassandra Clark, only fifteen years old.

This was less than a week before she disappeared, just three nights.

Sitting now in the warm spot and ashes Cassandra left on the sofa, Mrs. Clark looks through the folder of notes.

The gallery owner was talking to them, to them and the people gathered around.

“Rand,” her notes say. The owner's name was Rand.

The gallery owner was showing them a box on three tall legs. A tripod. The box was black, the size of an old-time camera. The kind of camera where a man might stand behind, hunched under a sheet of black canvas to protect the glass plate coated with chemicals inside. The kind of Civil War camera that took your picture with a flash of gunpowder. A mushroom cloud of gray smoke that hurt your nose. When you first walked into the gallery, that's how it looked, this box on three legs.

The box was painted black.

“Lacquered,” the gallery owner said.

It was lacquered black, waxed and smudged gray with fingerprints.

The gallery owner was smiling down the stiff, strapless front of Cassandra's dress. He had a thin mustache, plucked and trimmed perfect as two eyebrows. He had a little devil's beard that made his chin look pointed. He wore a banker's blue suit and a single earring, too big, too fake-bright to be anything but a real diamond.

The box was fitted along every seam with complicated moldings, ridges and grooves, that made it look heavy as a bank vault. Every seam hidden under detail and thick paint.

“Like a little coffin,” somebody in the gallery said. A man with a ponytail, chewing gum.

On each side of the box were brass handles. You had to hold them both, the gallery owner told them. To complete a circuit. If you wanted to make the box work right, you held both handles. You pressed your eye to the brass peephole in the front. Your left eye. And you looked inside.

Person after person, a hundred people must've looked that night, but nothing happened. They held on and looked inside, but all they saw was their own eye reflected in the darkness behind the little glass lens. All they heard was a little sound. A clock, ticking. Slow as the drip . . . drip . . . drip . . . from a leaky faucet. This little ticking from inside the smudged, black-painted box.

The box felt sticky with its layer of grime.

The gallery owner held up one finger. He tapped his knuckle against the side of the box and said, “Some kind of Random Interval Timer.”

It could run for a month, always ticking. Or it could run for another hour. But the moment it stopped, that would be the moment to look inside.

“Here,” the gallery owner said, Rand said, and he tapped a little brass push-button, small as a doorbell, on the side of the box.

You hold the handles, and you wait. When the ticking stops, he said, you look and push the button.

On a little brass nameplate, a plate screwed to the top of the box, if you stood on tiptoes, you could read “The Nightmare Box.” And the name “Roland Whittier.” The brass handles were green from people holding tight, waiting. The brass fitting around the peephole was tarnished with their breath. The black outsides were waxed with grease from their skin rubbing, pressed close.

Holding the handles, you could feel it inside. The ticking. The timer. Steady and forever as a heartbeat.

The moment it stopped, Rand said, the push-button would trigger a flash of light inside. A single pulse of light.

What people saw then, Rand didn't know. The box came from the closed antique shop across the street. There it had sat for nine years and never stopped ticking. The man who owned it, the antiques dealer, he always told customers it might be broken. Or it was a joke.

For nine years, the box sat ticking on a shelf, until dust buried it. Until, one day, the dealer's grandson found it, not ticking. The grandson was nineteen years old, going to college to become a lawyer. This teenager without a hair on his chest, all day girls came into the shop to use their eyes on him. A good kid with a scholarship playing soccer, a bank account, and his own car, he had a summer job at the antique shop, dusting. When he found the box, it was silent—ready and waiting. He took the handles. He pressed the button and looked inside.

The antiques dealer found him, dust still smeared around his left eye. Blinking. His eyes focused on nothing. He just sat in a pile of dust and cigarette butts he'd swept up on the floor. The grandson, he never went back to college. His car sat at the curb until the city towed it away. Every day after that, he sat in the street outside the shop. Twenty years old, and he sits on the curb all day, rain or shine. You ask him anything and he just laughs. That kid, by now he should be a lawyer, practicing law, but now you can go visit him in some fleabag hotel. Public housing, on Social Security for a complete mental depression. Not drugs even.

Rand, the gallery owner, says, “Just a case of total crackup.”

You go visit this kid, and he sits on his bed all day, cockroaches crawling in and out of his clothes, his pant legs and shirt collar. Each fingernail and toenail is grown long and yellow as a pencil.

You ask him anything: How he's doing? Is he eating? What did he see? And the kid still only laughs. Cockroaches moving around, lumps inside his shirt. His head circled with houseflies.

Another morning, the antiques dealer comes in to open his shop, and the dusty clutter is different. It could be someplace he's never been. Again, the box has stopped ticking. That always-quiet countdown. And the Nightmare Box sits there, waiting for him to look.

All morning, the dealer doesn't unlock the front door. People come and cup their hands against his window to peek inside. To look for something back in the shadows. For some reason why the shop isn't open.

In that same way, the antiques dealer could've peeked inside the box. To see why. To know what happened. What would take the spirit out of a kid, now twenty years old, a kid with everything to look forward to.

All morning, the antiques dealer watches the box not tick.

Instead of looking, the dealer scrubs the toilet bowl in the back. He hauls out a ladder and picks the dry, dead flies from each hanging light fixture. He polishes brass. Oils woods. He sweats until his starched white shirt is soft with wrinkles. He does everything he hates.

People from the neighborhood, his longtime customers, they come to the store and find the door locked. Maybe they knock. Then they go away.

The box waits to show him what for.

It's going to be somebody he loves who looks inside.

All his lifetime, this antiques dealer, he works hard. He finds good stock at a fair price. He carts it here and puts it on display. He wipes the dust from it. Most of his life, he's been in this one store, and already he's going to estate sales and buying back the same lamps and tables, selling them for the second and third times. Buying from dead customers to sell to live ones. His shop just inhaling and exhaling this same stock.

This same tide of chairs, tables, china dolls. Beds, cabinets, little knickknacks.

Coming in and going out.

All morning, the dealer's eyes keep coming back to the Nightmare Box.

He does his bookkeeping. All day, he fingers the ten-key adding machine, balancing accounts. Totaling and comparing long columns of numbers. Seeing the same stock, the same dressers and hat racks arrive and depart on paper. He makes coffee. He makes more coffee. He drinks coffee until the can of grounds is empty. He cleans until everything in the shop is just his reflection in buffed wood and clean glass. The smell of lemon and almond oils. The smell of his sweat.

The box waits.

He changes into a clean shirt. He combs his hair.

He calls his wife and says how, for years, he's been hiding cash in a tin box under the spare tire in the trunk of their car. Forty years ago, when their daughter was born, the antiques dealer tells his wife, he had an affair with some girl who used to come in on her lunchtime. He says he's sorry. He tells her not to hold dinner for him. He says he loves her.

Next to the telephone, the box sits, not ticking.

The next day, the police find him. His accounts balanced. His shop in perfect order. The antiques dealer's taken an orange extension cord and knotted it to the coat hook on his bathroom wall. In the tiled bathroom, where any mess would be easy to clean up, he's knotted the cord around his neck and then just—relaxed. He's sunk down, slumped against the wall. He's choked, dead, almost sitting on the tiled floor.

On the display counter, in the front of the store, the box is ticking, again.

This history, it's all in Tess Clark's thick folder of notes.

It's then the box comes here, to Rand's art gallery. By then, it's kind of a legend, Rand tells the little crowd. The Nightmare Box.

Across the street, the antique store is just a big painted room, empty behind its front window.

It was right then, that night, Rand showing them the box, Cassandra's arms bunched in tight to hold her dress up, it was that moment somebody in the crowd said, “It's stopped.”

The ticking.

It had stopped.

The crowd waited, listening to the quiet, their ears reaching out for any sound.

And Rand said, “Be my guest.”

“Like this?” Cassandra said, and she gave Mrs. Clark the tall glass of white wine to hold. She lifted one hand to the brass handle on that side. She handed Rand her beaded little evening bag, her little clutch, with her lipstick and emergency cash inside. “Am I doing this right?” she said, and lifted her other hand to the opposite handle.

“Now,” Rand said.

Mrs. Clark stood there, the mother, a little helpless with a full glass of wine in each hand, watching. Everything ready to spill or break.

Rand cupped his hand against the back of Cassandra's neck, the bare skin above her spine, where only a soft curl of hair fluttered down. At the top of her long-zippered ass. He pressed so her neck arched, her chin coming up a little and her lips moving open. Holding her neck in one hand and her purse in his other, Rand told her, “Look inside.”