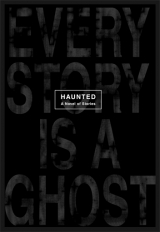

Текст книги "Haunted"

Автор книги: Charles Michael «Chuck» Palahniuk

Жанр:

Повесть

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

On the way down in the elevator, Angelique tells you this was her last foot job. This kind of foot hit paid a million bucks, cash. A rival agency had hired her to bump off Lenny, and now she was out of the business for good.

In the lobby bar, the two of you have a cocktail to get the taste of Lenny's foot out of her mouth. Just one last, good-bye drink. Then Angelique says to look around the hotel lobby. The men in suits. The women in fur coats. They're all Rolfing killers, she says. Reiki killers. Colonic-irrigation assassins.

Angelique says, in gem therapy, just by putting a quartz crystal on someone's heart, then an amethyst on his liver and a turquoise on his forehead, you induce a coma that results in death. Just by sneaking into a room and rearranging someone's bedroom set, a feng-shui expert can trigger kidney disease.

“Moxibustion,” she says, the science of burning cones of incense on someone's acupuncture points, “it can kill. So can shiatsu.”

She drinks the last of her cocktail, and takes off the strand of pearls from around her neck.

All those cures and remedies that claim to be 100-percent natural ingredients, therefore 100-percent safe, Angelique laughs. She says, Cyanide is natural. So is arsenic.

She hands the pearls to you and says, “From now on, I'm back to being ‘Lentil.'”

That's how you want to remember Angelique, not the way she looked in the newspaper the next day, fished out of the river in a soggy mink coat. Her earrings and diamond watch taken to make it look like a robbery. Not with her feet fondled to death, but dead the old-fashioned way, with a hollow-point bullet to the back of her perfect French braid. A warning to all the Dirks and Dominiques who might jump ship.

The clinic calls, not Lenny, but some other Russian accent, trying to send you to clients, but you don't trust them. The guards saw you with Lentil. Up at the penthouse. They must have another hollow-point ready for the back of your head.

Your folks call from Florida to say a black town car keeps following them, and somebody calls to ask if they know how to find you. By now, you're already running from flophouse to flophouse, giving back-alley foot jobs for enough cash to stay alive.

You tell your folks: Be careful. You tell them not to get massaged by anybody they don't know. Calling them from a pay phone, you tell them to never mess with aromatherapy. Auras. Reiki. Don't laugh, but you're going to be traveling for a long time, maybe the rest of your life.

You can't explain. By now, you've run out of quarters, so you tell your folks good-bye.

3

Our first week, we ate beef Wellington while Miss America knelt at every doorknob and tried to pick the lock with a palette knife borrowed from the Duke of Vandals.

We ate striped sea bass while Miss Sneezy ate pills and capsules from the rattling jars in her suitcase. While she coughed into her fist, and wiped her nose on her sweater sleeve.

We eat turkey Tetrazzini while Lady Baglady toys with her diamond ring. With the platinum band turned around, she talks to the big diamond that seems to sit cupped in her palm. “Packer?” she says. “This is nothing like I've been led to expect.” Lady Baglady says, “How can I write anything profound if my environment isn't . . . ideal?”

Of course, Agent Tattletale's videotaping her. The Earl of Slander holds his tape recorder to catch every word.

A cough-cough, here. A cough-cough, there. Here, a gripe. There, a bitch. Everywhere, a complaint. Miss Sneezy says the air is swimming with toxic mold spores.

A rattle-rattle, here. A cough-cough, there. No one working. No writing getting done.

Skinny Saint Gut-Free, his face was always looking up, his mouth baby-bird gaped open as he poured in chili or apple pie or shepherd's pie from a silver Mylar bag. His Adam's apple bobbed with each swallow, his tongue funneling the lukewarm mess past his teeth.

Chewing his tobacco, the Matchmaker spit on the stained carpet and said this dank building, these dim-dripping rooms, had nothing in common with the writers' colony he'd pictured: people writing longhand, looking down rolled green lawns; writers eating box lunches, each in their own private cottage. Orchards of apricot trees in a blizzard of white flower petals. Afternoon naps under chestnut trees. Croquet.

Even before she started to outline her screenplay, her life's masterpiece, Miss America said she couldn't. Her breasts were too sore to write. Her arms, too tired. She couldn't smell today's veal cutlets without vomiting a little of the crab cakes from the day before.

Her period was almost a week late.

“It's sick-building syndrome,” Miss Sneezy told her. Her raw-red nose, already staying sideways, wiped in profile against one cheek.

Trailing her fingers along the railings and the carved backs of chairs, Lady Baglady showed us the dust. “Look,” she told the fat diamond in her hand, she said, “Packer? Packer, this is not acceptable.”

In our first week locked away, Miss Sneezy was coughing, breathing in the slow, deep notes a pipe organ would make.

Miss America was rattling locked doors. Yanking aside the green velvet drapes in the Italian Renaissance lounge to find windows bricked over. With the handle of her pink plastic exercise wheels, she broke a stained-glass window in the Gothic smoking room, only to find a cement wall wired with bulbs to fake daylight behind it.

In the French Louis XV lobby, the chairs and sofas all cornflower-blue velvet, the walls crowded and busy with plaster curls and scrolls painted gold, there, Miss America stood in her pink spandex active wear and asked for the key. Her hair, an ocean wave of blond breaking in curls and flips against the back of her head, she needed the key so she could go out, just for a few days.

“You're a novelist?” Mr. Whittier said. Even resting flat on the chrome arms of his wheelchair, his fingers tapped an invisible telegram. Veined and chased with wrinkles, the bones of his hands trembled in a constant blur.

“A screenwriter,” Miss America said. A fist on each pink spandex hip.

Looking at her, tall and willowy, “Of course,” Mr. Whittier said. “So write a movie script about being tired.”

No, Miss America needed to see an obstetrician. She needed blood work done. She needed prenatal vitamins. “I need to see someone,” she said. Her boyfriend.

And Mr. Whittier said, “This is why Moses led the tribes of Israel into the desert . . .” Because those people had lived for generations as slaves. They'd learned to be helpless.

To create a race of masters from a race of slaves, Mr. Whittier said, to teach a controlled group of people how to create their own lives, Moses had to be an asshole.

Sitting at the edge of a blue velvet chair, Miss America kept nodding her blond head. Her hair flip-flopping. She understood. She understood. Then she said, “The key?”

And Mr. Whittier told her, “No.”

He balanced a silver Mylar bag of chicken Marsala on his knees, all around him the blue carpet patched and sticky with dark mold. Each soggy patch, a shadow branched with arms and legs. A mildewed ghost. Spooning up chicken Marsala, Mr. Whittier says, “Until you can ignore your circumstances, and just do as you promise,” he says, “you'll always be controlled by the world.”

“And what do you call this?” Miss America says, stirring the dusty air with her hands.

And Mr. Whittier says, for the first of a million times, “I'm only holding you to your word.” And, “What stops you here is what stops your entire life.”

The air will always be too filled with something. Your body too sore or tired. Your father too drunk. Your wife too cold. You will always have some excuse not to live your life.

“But what if something happened? What if we ran out of food?” Miss America says. “You'd open the door then, wouldn't you?”

“But we're not,” Mr. Whittier says, his mouth full of chewed chicken and capers. “We're not running out of food.”

And, no, we weren't. Not yet.

That first week inside, we ate vegetable curry over rice. We ate teriyaki salmon. All of it freeze-dried.

For food, we had green beans sealed in Mylar bags you couldn't tear with your bare hands. “Vermin-proof” was stenciled in black paint on each silver bag. We had vermin-proof green beans and chicken pot pie and golden-sweet whole-kernel corn. Inside each bag, something rattled, loose twigs and rocks and sand. Each bag inflated to a silver pillow with a puff of nitrogen to keep the contents dead. The lasagna with meat sauce or cheese ravioli.

Vermin-proof or not, our Missing Link could rip a bag open with his bare pubic-hairy hands.

To cook dinner, most people cut the bag open with scissors or a knife. You reached in and dug around until you found the little tea bag of iron oxide—added to absorb any trace of oxygen. You fished out the tea bag and dumped in so many cups of boiling water. We had a microwave. We had plastic forks and spoons. Paper plates. And running water.

You read ten pages in a vampire novel, and dinner was served. Instead of sticks and hot water, the silver pillow was full of home-style meatloaf or beef Stroganoff.

We'd sit on the blue carpet of the lobby stairs, a rippling blue waterfall, each step so wide we could all share the same one and our elbows not poke each other. This was the same beef Stroganoff the President and Congress would be eating deep underground during a nuclear war. It was from the same maker.

Other silver bags were stenciled “Chocolate Devil's Food Cake” and “Bananas Foster.” Mashed potatoes. Macaroni and cheese. Freeze-dried French fries.

All of it, comfort food.

Every bag had a good until date that wouldn't come until we were dead. A shelf life until after most babies would be dead.

Strawberry cupcakes with a hundred-year life span.

We ate freeze-dried lamb with freeze-dried mint jelly while Lady Baglady discovered in her heart's own heart that she really did love her dead husband. She loved him, she cried into her hands. Her shoulders hunched and jerking with sobs inside her mink coat. Cradling the fat diamond in her palm, she needed to get out and bury her three-carat husband in their family plot.

We ate Denver omelets while the Duke of Vandals snapped and popped his nicotine gum and said this was a terrible time to give up smoking. And Saint Gut-Free lost the feeling in his left hand, a repetitive-motion injury, trying to climax without a picture.

The cat of Director Denial, the cat named Cora Reynolds, ate leftover striped sea bass while Countess Foresight and the Reverend Godless worried we weren't safe enough. We'd walked into a trap. They worried someone might find us and . . . They told Mr. Whittier they needed to keep moving, hiding, running to stay safe.

Reverend Godless, clutching a Barbra Streisand album, his split, blood-sausage lips moving as he read the lyrics in the liner notes, he told the Earl of Slander's tape recorder, “I just assumed we'd have a stereo, here.”

In the viewfinder of Agent Tattletale's video camera, Chef Assassin lifted dripping green spoonsful of spinach soufflé into his fat face, saying, “I'm a professional chef. I'm not a food critic. But I can't go three months on instant coffee . . .”

Of course, everyone said they'd still write their work, their poems and stories. They'd complete their masterpiece. Just not here. Not now. Later, outside.

Our first week here, we got nothing done. Except complain.

“It's not an excuse,” Miss America said, holding her flat stomach in both hands, “it's a human life.”

Miss Sneezy coughed into her fist. She sniffed, her eyes bulging and bloodshot behind tears, and said, “My life's at stake, here.” One hand digging in her pocket for another pill.

And, of course, Mr. Whittier shook his head no.

Sitting there in his blue velvet chair, the lobby scrolling gold and velvet around him, Mr. Whittier spooned clam chowder out of a Mylar bag and said, “Tell me a story about the baby's father.” To Miss America, he said, “Write me the scene of how you met him.”

And Agent Tattletale's camera zoomed in on Miss America's face for a close-up reaction shot.

Product Improvements

A Poem About Miss America

“I'm always looking,” says Miss America, “for what's NOT to like.”

Every time she looks in a mirror.

Miss America onstage, her blond hair coils and spirals, billows and looms,

to make her face look as small as possible.

One high-heeled foot, placed just a little in front of the other

to make her legs overlap

so her hips look more

narrow.

Standing sideways, she twists her shoulders

to face the audience head-on.

All this breathless contortion to make her waist look

itty-bitty.

Onstage, instead of a spotlight, a movie fragment:

Her face veiled with exercise videos.

Her features, her eyes and lips, made up with hot-pink leotards and leg warmers.

Her Miss America skin jumps and dances with a crowd of women,

each of those women watching herself in a mirror.

The film: a shadow of a reflection of an image of an illusion.

She says, “My every glance in a mirror, it's a secret market survey.”

She's her own test audience.

Rating her curb appeal on a scale of one to ten.

Every day, beta-testing a new upgraded version of herself-point-five.

Fine-tuning to follow market trends.

Her dress, swimsuit-tight, leotard-tight,

her pantyhose run with women pedaling bicycles, going nowhere

at a thousand calories an hour.

“For the Talent portion of my program,” she says, “I'll show you how to unswallow.”

A bellyful of peach ice cream,

a Halloween bag of miniature candy bars,

six frosted doughnuts,

two double cheeseburgers.

The usual stuff.

And sometimes, sperm.

Her face swimming and flickering with aerobic work, her immediate ambition is

to diminish initial buyer resistance.

With a long-term goal of becoming someone's long-term investment.

As a durable consumer good.

Green Room

A Story by Miss America

It's nothing personal when bombs explode. Or when a gunman in a stadium takes a hostage. When the Net Monitor shows a special alert, any television station is going to toss to the talent on the national feed coming through.

If you're watching television, first the local booth producer and director will cut to the double-box format. A split screen to most people. Then the local talent says something like, “With the latest on the sinking ocean liner, here's Joe Blow in New York.” That's what they call “the toss.” Or “the kick.”

The network feed takes over, and the local boys sit on their hands and wait for the network bump to signal the end of the special-alert feed.

No publicist thinks to explain all this to each newbie they send on the road, selling an investment video, a book, a new-fangled carrot peeler.

So, sitting in the green room, backstage at Wake Up Chattanooga!, a young guy with his hair slicked back, he explains some facts of life to this blonde.

She's super, way-too blond, he tells her. That kind of bleach blond, it drives the floor producer nuts, because you can't light it well without it flaring. Some floor producers, they call it “blowout.” The blond head just looks on fire.

“Whatever you do,” the slick guy tells the blonde, “if you got notes, don't reference them or the camera will be shooting the top of your head.”

Floor producers, he says, they hate guests who bring notes. They hate guests who don't try to bury their agenda. Producers will tell you: “Be your product. Don't push it.”

Ironical, but that same floor producer will call you “Fitness Wheel” because that's the slug written in your block on the schedule. It says “Investment Videos” for the slick guy's block. For the old man, the slug says: “Stain Remover.”

The blonde and the slick guy, them sitting on the reject leather sofa in the green room, cups of old coffee abandoned on the table in front of them, hanging over them a couple video monitors flicker high on the walls, in the corners, mounted up near the ceiling. On one monitor, you see the national talent talking about the ocean liner, then tossing to video support that shows a ship belly-up and the specks of orange life vests floating around it. On the second monitor, the blonde says, there's something even sadder.

Up in that other corner, you see the A Block bozo, the old comb-over guy who got out of his Motel 6 bed at 5 a.m. to be here and pitch his special stain-removing brush he invented. Poor schmuck. He gets miked and put onstage, in the “living-room set” with its rain forest of fake plants. He sits under those hot lights while the on-air talent does their opening “chat.”

The living-room set is different from the “kitchen set” and the “main set” because it has more fake plants and throw pillows.

This bozo thinks he's got a fat ten-minute segment because the station is playing the clock, not cutting to commercial until ten after the start. Most stations cut at eight or nine minutes. That way, we keep the audience from channel-surfing and get top ratings credit for the whole fifteen-minute block.

“Not pretty,” the slick guy tells our blonde girl, and he crosses himself fast as a good Catholic, “but better him than either of us.”

A heartbeat into his stain-removing demo, the A Block's cut off by the doomed ocean liner.

Sitting in this green room, on a ratty leather sofa in some double-digit ADI, the slick guy says he's got maybe seven minutes to teach an entire world to our Miss America.

ADI, that means Area of Direct Influence. Boston, for example, is the number-three ADI in the country because its media reach the third-largest market of consumers. New York is the number-one ADI. Los Angeles is number two. Dallas, number seven.

Where they're sitting is way down the list of ADIs. Day Break Lincoln or New Day Tulsa. Some media outlet that reaches a consumer market demographic totaling nobody.

Some other good advice is: Don't wear white. Never wear a black-and-white patterned anything because it will “shimmer” on camera. And always lose some weight.

“Just staying at this weight,” our blonde tells the slick guy, “is a full-time job.”

The on-air person, the talent here in Chattanooga, the slick guy says, the anchor here is a total straight pipe. Whatever they tell her over the IFD in her ear, those exact words will pop out her lipstick-red mouth. The director could feed her, “. . . Christ, we're going long! Toss to Adopt-a-Dog, and then we'll cut to commercial . . . ,” and that's what she'd say on air.

A total straight pipe.

Our blonde girl, listening, she doesn't laugh. Not even a smile.

So the slick guy tells her, other talent he's seen, one time on a live feed to location, a warehouse fire roaring in the background, the on-air person fumbled with her hair, looking straight into a hot camera and going out live, she said, “Could you repeat the question? My IUD fell out . . .”

The reporter, she meant IFD. Internal Feedback Device, the slick guys says. He points at the anchor who appears on the monitor, and he says how one anchor will always have that kind of lopsided hairdo. The hair swooping down to hide one ear. It's because she's got a tiny radio stuck in her ear to take prompts and cues from the director. If the show is going long or they need to toss to a nuclear-reactor meltdown.

This blonde, she's on the road with some kind of exercise wheel you roll around on top of to lose weight. She wears a pink leotard and purple tights.

Yeah, she's thin and blonde, but the more ins and outs your face has, the slick guy tells her, the better you look on camera.

“That's why I have to keep my before picture,” she says. Bending over in her chair, leaning over and over until her breasts press against her knees, she digs in a gym bag on the floor. She says, “This is the only real proof that I'm not just another skinny blonde girl.” She takes something paper out of the bag, holding an edge between two fingers. It's a photograph, and the blonde tells the slick guy, “Unless people see this, they might think I was just born this way. They'd never know what I've done with my life.”

Go on television with even a little baby fat, he tells her, and you look like nothing. A mask. A full moon. A big zero with no features for people to remember.

“Losing all that blubber is the only really heroic thing I've ever done,” she says. “If I gain it back, then it'll be like I never lived.”

You see, the slick guy says, television takes a three-dimensional thing—you—and turns it into a two-dimensional thing. That's why you look fat on camera. Flat and fat.

Holding the photo between two fingernails, looking at her old self, our blonde says, “I don't want to be just another skinny girl.”

About her hair being too “hot,” the slick guy tells her, “That's why you never see natural redheads in porn movies. You can't light them right, next to real people.”

That's what this guy wants to be: the camera behind the camera behind the camera giving the last and final truth.

We all want to be the one standing farthest back. The one who gets to say what's good or bad. Right or wrong.

Our too-blonde girl, going to blow out the cameras, the slick guy tells her about how these local-produced shows are broken into six segments with commercials in between. The A Block, B Block, C Block, and so on. These shows like Rise and Shine Fargo or Sun-Up Sedona, they're a dying breed. Expensive to produce, compared to just buying some national talk-show product to fill the slot.

A promotion tour like this, it's the new vaudeville. Going from town to town, hotel to hotel, playing one-night stands on local television and radio. Selling your new and improved hair curler or stain remover or exercise wheel.

You get seven minutes to put your product across. That's if you're not slotted in the F Block—the last block, where in half the ADIs you get bumped off the program because an earlier block went too long. Some guest was so funny and charming they held him through the commercial. They “double-blocked” him. Or the network interrupted with a sinking ship.

That's why the A Block is so choice. The show starts, the anchors do their “chat” segment, and you're on.

No, pretty soon, all this hard-won know-how the slick guy's put together, it will be no good to anybody.

Maybe that's why he's teaching her for free. Really, he says, he should write a goddamn book. That's the American Dream: to make your life into something you can sell.

Still looking at her fat-self photograph, the blonde says, “It's pretty creepy, but this fatty-fat picture is worth more to me than anything,” she says. “It used to make me sad, looking at it. But now it's the only thing that cheers me up.”

She holds out her hand, saying, “I eat so much fish oil you can smell it.” She wiggles the photo at the slick guy, saying, “Smell my hand.”

Her hand smells like a hand, like skin, soap, her clear fingernail polish.

Smelling her hand, he takes the picture. Flattened out on paper, made into just height and width, she's a cow wearing a cropped top over low-rise jeans. Her old hair is a normal, average brown color.

If you look at what the slick guy's wearing, a pale-pink shirt with a robin's-egg-blue tie, a dark-blue sports coat, it's perfect. The pink warms up his flesh tones. The blue picks out his eyes. Before you even open your mouth, he says, you have to be presentable. Presentable, well-groomed broadcast content. You wear a wrinkled shirt, a stained tie, and you'll be the guest they cut if they run short of time.

Any television station just wants you to be clean, well-groomed, charming content. Camera-friendly content. A nice face, because a stain remover or an exercise wheel can't talk. Just happy, high-energy content.

On the monitor, the skin hanging off the old guy's neck, it's folded and pleated together where it has to tuck into his starched blue button-down collar. Even so, as he swallows, just sitting there, some extra skin spills out over the top of his collar, the way the before-photo girl's belly fat spills over the waist of her jeans.

This photo doesn't even look like the same girl. Mainly because in the picture she's smiling.

Looking at the green-room monitor, the slick guy points out how the hot camera never pans over the audience, never gives us a wide shot. That means the place is nothing but old ladies with bad teeth. The audience-recruitment person, he must've worked a deal. They drag these goobers in here at 7 a.m. and fill an audience, and the station will plug their Senior Craft Fair. That's how they stock these local shows with people to clap. Around Halloween, it will be all young people coming in, so the station will plug their haunted-house fund-raiser. Around Christmas, those bleachers are nothing but old folks who want their charity bazaars to get some attention. Fake applause traded for free advertising.

On the broadcast monitor, the national talent kicks the show back to the local anchor, who tosses to a pre-pro package tease about tomorrow's makeover show, then the bump: a beauty shot of the rain falling outside, a little fanfare, and we're into commercial.

The ship's sunk, with hundreds dead. Film at eleven.

The slick guy's investment pitch, he's rewriting it inside his head to include Acts of God. Disasters you can't predict. And how vitally important a good, sound investment plan can be to the people depending on you. Him, being his product. Hiding his agenda.

Him, the camera behind the camera.

Long as it took that ocean liner to sink, it looks as if our bleach blonde's hair will get her bounced off.

Before they come back from commercial, bumping with a traffic report, a voice-over and the live shot from some highway camera, before then the producer will escort the stain remover back to the green room. The floor producer, she'll hand the radio mike to the Investment Video. She'll tell the Fitness Wheel, “Thank you for coming down, but we're sorry. We overbooked and ran long . . .”

And she'll have Security escort our blonde out to the street.

All so they can wrap and meet the network feed—the soap operas and celebrity talk shows—at ten o'clock, sharp.

The old goober up on the monitor, he's got the same shirt and tie as the slick guy. The same blue eyes. He's got the right idea. Just the wrong timing's all.

“Let me do you a favor,” the slick guy tells the blonde. Still holding the before fat picture of her, he says, “Will you take some good advice?”

Sure, she says, anything. And, listening, she picks up a cup of cold coffee with lipstick smeared on the paper rim that matches the pink lipstick on her mouth.

This blonde girl with her too-hot hair, she's the slick guy's own private personal ADI right now.

Especially, he tells her, don't let any of these daytime-talk-show Romeos get you into bed. He doesn't mean the on-air talent. It's the pitch guys you have to watch, these same guys you meet selling their miracle dust mops and get-rich schemes in city after city. You'll be thrown together in green rooms in ADIs all across the country. You and them lonely from your time stuck out on the road. Nothing but a motel room at the end of each day.

Speaking from personal experience, these green-room romances go nowhere.

“You remember the Nev-R-Run Pantyhose Girl?” he asks her.

And the blonde girl nods yes.

“She was my mom,” the slick guy says. She met his dad while they were both on selling tours, meeting again and again in green rooms just like this. Truth is, he never married her. Ditched her as soon as he found out. Being pregnant, she lost the pantyhose pitchman contract. And the slick guy grew up watching shows like Out-a-Bed Boulder and Wakey Wakey Tampa, trying to figure out which of those smiling fast-talking men was his old man.

“It's why I'm in the business,” he tells our blonde girl.

That's why: keep it business, is his first rule.

The blonde says, “Your mom is really, really pretty . . .”

His mom . . . He says, Those Nev-R-Run Pantyhose must've used asbestos. She caught cancer a couple months back.

“She was damn ugly,” he says, “when she died.”

At any second, the door into the green room will swing open, and the floor producer will come in, saying she's sorry but they might need to cut another guest. The producer, she'll look at the girl's bright-blond hair. The producer will look at the slick guy's navy-blue sports coat.

The F Block bailed out of here the moment the network broke in with the ocean liner. Then the E Block—Color Consultant, her slug said—bailed when the show looked doomed to run long. Then a Children's Book slotted for the D Block took off.

The sad truth is, even if you get your hair the right color blond and fake being funny and high-energy, good content, even then some terrorist with a box cutter might still walk off with your seven-minute segment. Sure, they can always tape you and run you packaged the next day, but chances are they won't. They've got content booked solid for this week, and running you on tape tomorrow means cutting someone else . . .

In their last minute alone, just them in the green room, the slick guy asks if he can do our blonde girl another favor.

“You want to give me your block?” she says. And she smiles, just like in the picture. And her teeth aren't too awful.

“No,” he says. “But when somebody's being charming . . . when they tell you a joke . . . ,” the slick guy says, and he tears her ugly before picture in half. The two halves he puts together and tears into quarters. Then eighths. Then whatever. Shreds. Little bits. Confetti. He says, “If you're going to succeed on television, you need to at least fake a smile.”

At least pretend to like people.

There in the green room, the blonde's pink-lipstick mouth, it peels open and open and open until it hangs. Her lips go open and shut two, three times, the way a fish will gasp for breath, and she says, “You ass . . .”

It's then the floor producer walks in with the old goober.

The producer says, “Okay, I think we'll go with the investment video for this last segment . . .”

The old goober looks at the slick guy, the way you'd look at some department-store buyer who orders a half-million units, and he says, “Thomas . . .”

The blonde's just sitting there, holding her cup of cold black coffee.