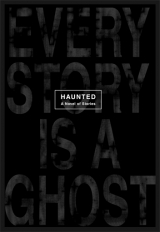

Текст книги "Haunted"

Автор книги: Charles Michael «Chuck» Palahniuk

Жанр:

Повесть

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

The box is quiet. Silent the way a bomb might be the moment before it goes off. Explodes.

Cassandra opens up the left side of her face, her eyebrow held high, her eyelashes on that side trembling, thick with black mascara. Her green eye, wet and soft, something between solid and liquid, she puts her eye against the little glass, the darkness inside.

The crowd around them. Waiting. Rand still holding the back of her neck.

One painted fingernail moves to the button and, Cassandra's face pressed to the black wood of the box, she says, “Tell me when.”

The way you have to look inside, to make your face fit against the box, you have to turn your face a little to the right. You have to stoop a little, leaning too far forward. You have to hold both handles because this puts you off balance. Your weight, it has to rest against the box, pressing through your hands, balancing on your face.

Cassandra's face against the black, complicated corners and angles of the old box. The way she might be kissing it. The trembling curls of her hair. The sparkling dangle of each bright earring.

Her finger moves on the button.

And the ticking starts again, faint and deep inside.

What happens, only Cassandra sees it.

The random timer starts again for another week, another year. Another hour.

Her face stays there, pressed into the peephole, until her shoulders sag. She stands, her arms still hanging down, her shoulders go round and sloped.

Blink-blinking her eyes, fast, Cassandra steps back and shakes her face a little. Her eyes not meeting anyone's eyes, Cassandra looks around at the floor, at people's feet, her lips shut tight. The stiff front of her dress bags forward, gapping out away from her breasts with no bra inside. She reaches out and pushes herself back from the box.

She steps out of each high heel, standing flat-footed on the gallery floor, and the muscles in her legs disappear. The two rock-hard halves of her ass, they go soft.

A mask of loose hair hangs in her face.

If you're tall enough, you can see her nipples.

Rand says, “Well?” He clears his throat, pushing breath out through a long sound of spit and snot, and he says, “What did you see?”

And, still not looking at anyone, her eyelashes still pointing at the floor, Cassandra reaches a hand up and plucks the earring from each side of her head.

Rand reaches to give her the little beaded purse, but Cassandra doesn't take it. Instead, she hands him her jewelry.

Mrs. Clark says, “What happened?”

And Cassandra says, “Can we go home now?”

They listen to the box tick.

It's a couple days later she cut off her eyelashes. She flopped a suitcase open across the foot of the bed and she started putting things in, shoes and socks and her underwear, then taking things out. Packing and repacking. After she disappeared, the suitcase was still there. Half full or half empty.

Now all Mrs. Clark has are her notes, her thick folder full of notes about how the Nightmare Box must work. Somehow it must hypnotize you. It implants an image or an idea. A subliminal flash. It injects some message into your brain so deep you can't retrieve it. You can't resolve it. The box infects you this way. It makes everything you know wrong. Useless.

What's inside the box is some fact you can't unlearn. Some new ideas you can't undiscover.

Days after they went to the art gallery, now Cassandra's gone.

On the third day, Mrs. Clark goes downtown. Back to the gallery. Her thick brown folder of notes tucked under one arm.

The street door's unlocked and the lights are off. In the gray light from the windows, Rand is there, sitting on the floor in a dusting of cut hair. His little devil's beard is gone. His fat diamond earring, gone.

Mrs. Clark says, “You looked, didn't you?”

The gallery owner just sits there, sprawled, legs spread on the cold concrete, looking at his hands.

Mrs. Clark sits cross-legged on the floor next him and says, “Look at my notes.” She says, “Tell me I'm right.”

The way the Nightmare Box works, she says, is because the front is angled out on one side. It forces you to put your left eye against the peephole. It has a little glass fish-eye lens, set in a brass fitting, the same kind you'd find in anyone's front door. The way the front of the box is angled, the only way you can look is with your left eye.

“This way,” Mrs. Clark says, “what you see, you have to perceive with your right brain.”

Whatever you see inside, it's the intuitive, emotional, instinctual side of you, the right-brain part, that has to witness it.

Plus, only one person can look each time. What you suffer, you suffer it alone. What happens inside the Nightmare Box, it only happens to you. There's no one you can share it with. There's no room for someone else.

Plus, the fish-eye lens, she says, it warps what you see. It distorts.

Plus, she says, the name engraved on the brass plate—The Nightmare Box—it tells you that you'll be scared. The name creates an expectation that you fulfill.

Mrs. Clark sits and waits to be right.

She sits, watching for Rand to blink.

The box stands over them on its three legs, ticking.

Rand doesn't move except his chest, to breathe.

On his desk, near the back of the gallery, there's still Cassandra's jewelry. Her little beaded purse.

“No,” Rand says. He smiles and says, “That's not it.”

The ticking counts down, loud in the cold quiet.

You can only call the hospitals, asking if they have a girl with green eyes and no eyelashes. You can only call so many times, Mrs. Clark says, before they start not to hear you. To put you on hold. Make you give up.

She looks up from her thick stack of paper, her notes, and says, “Tell me.”

The antique store, it's still empty across the street.

“This isn't what happened,” Rand says. Still just looking at his hands, he says, “But this is how it felt.”

One weekend, he had to go to a company picnic for a job he used to have. A job he hated. And as a joke, instead of food, he brought a wicker crate full of trained doves. To everyone, this was just another picnic basket, more pasta salad and wine. Rand kept the hamper under a tablecloth all morning, keeping it shaded and cool. Keeping the doves inside quiet.

He snuck them crumbs of French bread. He squeezed bits of corn polenta through holes in the wicker.

All morning, the people he worked with, they sipped wine or sparkling water and talked about corporate goals. Mission statements. Team building.

At the moment when it seemed they'd all wasted a beautiful Saturday morning, that moment when all the small talk comes to an end, Rand says that's when he opened the hamper.

People. These people who worked together every day. Who thought they knew each other. As this white chaos. This storm exploded up from the center of the picnic. Some people screamed. People fell back into the grass. They covered their faces with their open hands. Food and wine fell. Good clothes got stained.

It was the moment after when people saw it wouldn't hurt them. When people saw this was safe. It was the most lovely thing they'd ever seen. They fell back, too amazed to even smile. For the countless hours of that one long moment, they forgot everything important and watched the cloud of white wings twist up into the blue sky.

They watched it spiral. And the spiral open. And the birds, trained by many trips, follow each other away to someplace they knew every time was their real home.

“That,” Rand says, “is what's inside the Nightmare Box.”

It's something that goes beyond life-after-death. What's in the box is proof that what we call life isn't. Our world is a dream. Infinitely fake. A nightmare.

One look, Rand says, and your life—your preening and struggle and worry—it's all pointless.

The grandson crawling with cockroaches, the antiques dealer, Cassandra with no eyelashes wandering off naked.

All your problems and love affairs.

They're an illusion.

“What you see inside the box,” Rand says, “is a glimpse of the real reality.”

The two people still sitting there, together on the concrete gallery floor, the sunlight from the windows and the street noise, it all feels different. It could be somewhere they've never been before. It's right now the ticking from the box, it's stopped.

And Mrs. Clark was too afraid to look.

13

We have no food. No hot water. Pretty soon, we may be trapped here in the dark, Brailling our way from room to room, feeling, hand over hand, every moldy, soft patch of the wallpaper. Or crawling over the sticky carpet, our hands and knees crusted, heavy with dried mouse turds. Touching every stiff carpet stain, branched with arms and legs.

We have no heat, now that the furnace is broken, again—the way it should be.

Every so often, you hear Saint Gut-Free shout for help, but a shout soft as the last echo off a wall a long ways away.

The Saint calls himself the People's Committee for Getting Attention. All day, he's walking the length of every outside wall, banging on the locked metal fire-doors, screaming. But only banging with his open hand. And not yelling too loud. Just loud enough to say he tried. We tried. We made the best of the situation by being brave, strong characters.

We organized committees. We stayed calm.

We're still suffering, despite the ghost who snaked the sewer pipes one night and got the toilets to work. The ghost used pliers to turn the gas back on to the water heater, after Comrade Snarky threw away the valve handle. It even spliced the power cord to the washing machine and started a load of clothes.

To the Reverend Godless, our ghost is the Dalai Lama. To the Countess Foresight, it's Marilyn Monroe. Or it's Mr. Whittier's empty wheelchair, the chrome shining in his room.

During the rinse cycle, the ghost adds fabric softener.

With collecting the lightbulbs and shouting for help and undoing the ghost's good deeds, we have almost no time left over. Just keeping the furnace broken is a full-time job.

What's worse is, this is nothing we can put in the final screenplay. No, we have to look in pain. Hungry and hurting. We should be praying for help. Mrs. Clark should be ruling us with an iron fist.

None of this is going bad enough. Even our hunger is less than we'd want. A letdown.

“We need a monster,” Sister Vigilante says, her bowling ball in her lap and her elbows propped on it. Using a knife to pry up her fingernails, wedging the knife tip under and rocking the blade side to side to pop each nail up, then pull it off, she says, “The basis of any horror story is, the building has to work against us.”

Flicking away each fingernail, she shakes her head, saying, “It doesn't hurt when you think how much money the scars are worth.”

It's all we can do not to drag Mrs. Clark out of her dressing room and force her at knife point to bully and torture us.

Sister Vigilante calls herself the People's Committee for Finding a Decent Enemy.

Director Denial limps around with both feet wrapped in silk rags. All of her toes hacked off. Her left hand is nothing, just a paddle of skin and bone, just the palm, with all the fingers and thumb hacked off, this paddle wrapped huge with rags. Her right hand is just her thumb and index finger. Between them, she holds a severed finger with her dark-red polish still on the nail.

Holding this finger, the Director walks from room to room, the Arabian Nights gallery to the Italian Renaissance lounge, her saying, “Here, kitty, kitty, kitty.” Saying, “Cora? Come to Mama, Cora, my baby. Dinner's ready . . .”

Every so often, you hear the voice of Saint Gut-Free shouting soft as a whisper, “Help us . . . Someone, please, help us . . .” Then the soft clap of his hands patting the exit doors.

Extra soft and quiet, just in case someone is right outside.

Director Denial calls herself the People's Committee for Feeding the Cat.

Miss Sneezy and the Missing Link, they're the People's Committee for Flushing the Rest of the Ruined Food. With every bag they flush, they force down a cushion or a shoe, anything that will make sure the toilets stay clogged.

Agent Tattletale knocks at Mrs. Clark's dressing-room door, saying, “Listen to me.” Saying, “You can't be the victim, here. We've voted you the next villain.”

Agent Tattletale calls himself the People's Committee for Getting Us a New Devil.

The lightbulb “peaches” the Matchmaker picks, that he lowers to Baroness Frostbite . . . That she packs so careful into boxes padded with old wigs . . . At the end of every day, the Earl of Slander takes them to the subbasement and breaks them on the concrete floor. He throws them the exact same way he'll tell the world Mrs. Clark broke them.

Already, the rooms seem bigger. Dimmer. The colors and walls disappear into the dark. Agent Tattletale videotapes the broken bulbs and Sister Vigilante's thrown-away fingernails on the floor. Identical half-moon shards of white.

Despite the ghost, our life is almost bad enough.

To Sister Vigilante, the ghost is a hero. She says we hate heroes.

“Civilization always works best,” Sister Vigilante says, picking the knife under another fingernail, “when we have a bogeyman.”

Voir Dire

A Poem About Sister Vigilante

“Some man sued for a million bucks,” Sister Vigilante says, “because of a dirty look.”

On her first day doing jury duty.

Sister Vigilante onstage, she holds a book to shield the front of her blouse.

Her blouse, frilly-yellow and edged with white lace.

The book, black leather with the title stamped in gold leaf across the cover:

Holy Bible

On her face, black-framed eyeglasses.

Her only jewelry, a charm bracelet of jiggling, trembling silver reminders.

Her hairdo dyed the same deep black as her shoe polish. As her Bible.

Onstage, instead of a spotlight, a movie fragment:

Each lens of her glasses, it glares with the reflected image of electric chairs

and gallows. Grainy newsreel footage of prisoners sentenced to the gas chamber

or the firing squad.

Where her eyes should be,

no eyes.

That first day on jury duty, the next trial, a man tripped over a curb and sued

the luxury car he fell against.

Asking an award of fifty grand for being such a stupid butterfingers.

“All these people with no sense of physical coordination,” Sister Vigilante says.

They all had excellent blaming skills.

Another man wanted a hundred grand from a homeowner who left the garden hose

stretched across the backyard that tripped him,

breaking his ankle,

while he fled from the police in an otherwise totally unrelated case

of rape.

This crippled rapist, he wanted a fortune for his pain and suffering.

There, up onstage, the silver charms flashing against the lace of her cuff,

her Bible gripped between the fingers of both hands,

her fingernails painted the same yellow as her frills,

Sister Vigilante says she pays her taxes on time.

She never jaywalks. Recycles her plastic. Rides the bus to work.

“At that point,” says Sister Vigilante, her first day of jury duty, “I told the judge”

Some charm-bracelet version of:

“Fuck this shit.”

And the judge held her in contempt . . .

Civil Twilight

A Story by Sister Vigilante

It was the summer people quit complaining about the price of gasoline. The summer when they stopped bitching about what shows were on television.

On June 24, sunset was at 8:35. Civil twilight ended at 9:07. A woman was walking uphill on the steep stretch of Lewis Street. On the block between 19th and 20th Avenues, she heard a pounding sound. It was the sound a pile driver might make, a heavy stomping sound she could feel through her flat shoes on the concrete sidewalk. It came every few seconds, getting louder with each stomp, getting closer. The sidewalk was empty, and the woman stepped back against the brick wall of an apartment hotel. Across the street, an Asian man stood in the bright glass doorway to a delicatessen, drying his hands on a white towel. Somewhere in the dark between streetlights, something glass broke. The stomp came again and a car alarm wailed. The stomp came closer, something invisible against the night. A newspaper box blew over sideways, crashing into the street. The crash came again, she says, and the windows blew out of a glass telephone booth only three parked cars away from where she stood.

According to a small item in the next day's newspaper, her name was Teresa Wheeler. She was thirty years old. A clerk at a law firm.

By then the Asian man had stepped back into the deli. He turned the sign around to say: Closed. Still holding the hand towel, he ran to the back of the store, and the lights went out.

Then the street was dark. The car alarm wailing. The stomp came again, so heavy and close by, Wheeler's reflection shimmered as the glass in the dark deli windows shook. A mailbox, bolted to the curb, it boomed loud as a cannon, then stood shaking, vibrating, dented and leaning to one side. A wooden utility pole shuddered, the cables draped across it rattling against each other, the sparks sprinkling down, bright summer fireworks.

A block downhill from Wheeler, the Plexiglas side of a bus shelter, the backlighted photograph of a movie star wearing just his underpants, the Plexiglas exploded.

Wheeler stood, stuck there flat against the brick wall behind her, her fingers worked into the joints between each brick, her fingertips touching mortar, clinging tight as ivy. Her head held back so hard that when she showed the police, when she told them her story, the rough brick had worn a bald spot in her hair.

Then, she said, nothing.

Nothing happened. Nothing had gone by in the dark street.

Sister Vigilante, telling this, she's worming a knife under each of her fingernails and prying off the nail.

Civil twilight, she says, is the period of time between sunset and when the sun is more than six degrees below the horizon. That six degrees equals about half an hour. Civil twilight, Sister Vigilante says, is different from nautical twilight, which lasts until the sun is twelve degrees under the horizon. Astronomical twilight goes until the sun is eighteen degrees below the horizon.

The Sister says, that something no one ever saw, downhill from Teresa Wheeler, it crumpled the roof of a car, waiting at a red light near 16th Avenue. The same invisible nothing wiped out the neon sign for The Tropics Lounge, crushed the neon tubing and folded the steel sign in half where it hung near a third-floor window.

Still, there was nothing to describe. Effect without cause. An invisible riot run amok on Lewis Street, all the way from 20th Avenue to somewhere near the waterfront.

On June 29, Sister Vigilante says, sunset was at 8:36.

Civil twilight ended at 9:08.

According to a guy working the box office of the Olympia Adult Theater, something rushed past the glass front of his ticket booth. This was nothing he could see. It was more the sound of air, an invisible bus going past, or an enormous exhale, so close it fluttered the paper money he had stacking in front of him. Just a high-pitched sound. At the edge of his sight, the lights of the diner across the street, they fluttered, blinked, as if something blotted out the whole world for an instant.

In the next breath, the ticket taker, he described the pounding sound first reported by Teresa Wheeler. A dog barked, somewhere in the dark. It was a walking sound, the kid in the box office would tell police. The sound of something taking huge steps. Just one huge foot he never saw swing past, only as far as one breath away.

On July 1, people were complaining about the water shortage. They were griping about city budget cuts and all the police getting laid off. Car prowls were on the rise. Spray-paint tagging and armed robbery.

On July 2, they weren't.

On July 1, sunset was at 8:34, with civil twilight ending at 9:03.

On July 2, a woman walking her dog found the body of Lorenzo Curdy, the side of his face caved in. Dead, Sister Vigilante says.

“Subarachnoid hemorrhage,” she says.

The moment before he was hit, the man must've felt something, maybe the rush of air, something, because he put his hands up in front of his face. When they found him, both hands were buried, punched so deep in his face his fingernails had dug into his own crushed brain.

On a street, the moment you're between streetlights, there in the dark you'd hear it. The stomp. Some people called it a clomping sound. You might hear a second sound from closer, somewhere nearby, or, worse, the next victim would be you. People heard it coming, once, twice, closer, and they froze. Or they forced their feet, left, right, left, three or four steps into a close-by doorway. They crouched, cowering next to parked cars. Closer, the next stomp came, a crash and a car alarm wailing. It was coming down the street, sounding closer, getting loud and gaining speed.

In the pitch-dark, Sister Vigilante says, it would hit—bam—a bolt of black lightning.

On July 13, sunset at 8:33 with civil twilight over at 9:03, a woman named Angela Davis had just left work at a dry cleaner's on Center Street when nothing hit her square in the middle of her back, breaking her spine so hard it lifted her out of her shoes.

On July 17, when civil twilight ended at 9:01, a man named Glenn Jacobs stepped off a bus and started up Porter Street toward 25th Avenue. What nobody saw, it slammed into him so hard his ribcage collapsed. His chest punched in the way you'd crush a wicker basket.

July 25, civil twilight ended at 8:55. Mary Leah Stanek was last seen jogging along Union Street. She stopped to tie one tennis shoe and check her pulse against her wristwatch. Stanek pulled off the baseball cap she wore. She turned it backward and put it back on, tucking her long brown hair up under it.

She headed west on Pacific Street, and then she was dead. Her face torn loose from the skull and muscle underneath.

“Avulsion,” Sister Vigilante says.

What killed Stanek, it was wiped clean of fingerprints. Clotted with blood and hair. They found the murder weapon wedged under a parked car down along 2nd Avenue.

It was a bowling ball, the police reported.

Those smudged, greasy-black bowling balls, you can buy them at any thrift shop for half a buck. You can pick and choose, they have bins of them. Somebody buying over a stretch of time, say one ball each year from every junk store in town, that person could have hundreds. Even in bowling alleys, it's simple to walk out with an eight-pound ball under your coat. A twelve-pound ball tucked in a baby stroller, a barely concealed weapon.

The police held a press conference. They stood in a parking lot and someone threw a bowling ball down, threw it hard against the concrete. And the ball bounced. It made the sound of a pile driver far away. It bounced high, taller than the man who threw it. It didn't leave a mark, and if the sidewalk were sloped, the police said, it would keep going, bouncing higher, faster, bouncing downhill in long strides. They threw it down from a third-story window in police headquarters, and the ball bounced even higher. The television news crews got it on tape. Every station played it that night.

The city council pushed for a law to paint all balls bright pink. Or neon yellow, orange, or green, some color you could see flying at your face down a dark side street late at night. To give people just a moment to dodge before—blam—their face is gone.

City fathers, they pushed for a law to make owning black balls a crime.

The police called it a nonspecific-motive killer. Like Herbert Mullin, who killed ten people to prevent southern-California earthquakes. Or Norman Bernard, who shot hobos because he thought it would help the economy. What the Federal Bureau of Investigation would call personal-cause killers.

Sister Vigilante says, “The police thought the killer was their enemy.”

The bowling ball was a police cover-up, people said. The bowling ball was a red herring. A monster wannabe. The bowling ball was a quick fix to keep everybody calm.

On July 31, the sun was six degrees under the horizon at 8:49. That night, Darryl Earl Fitzhugh was homeless, sleeping on Western Avenue. Open across his face, Fitzhugh had a paperback copy of Stranger in a Strange Land when his chest was crushed, both his lungs collapsed, and his heart muscle ruptured.

According to one witness, the killer came out of the bay, dragging itself over the lip of the seawall. Another witness saw the monster, dripping ooze, squeezing up from the storm sewer. These same people said the forensic evidence was consistent with a hard backhanded slap from a giant lizard walking on its hind legs. The ribcage collapsed was sure proof the victim was stepped on by some dinosaur throwback.

Something dashed past, other people said, something low to the ground, too fast to be an animal. Or it was a maniac run amok with a fifty-pound sledgehammer. One witness, she said we were being “smote” by God from the Old Testament. Swatted by something with a huge paw. Black as the black night. Silent and invisible. Everyone saw something different.

“What matters,” Sister Vigilante says, “is, people need a monster they can believe in.”

A true and horrible enemy. A demon to define themselves against. Otherwise, it's just us versus us.

Working the tip of the knife blade under another nail, she says, What's important is, the crime rate went down.

In times like that, every man is a suspect. Every woman, a potential victim.

Public attention went this same way during the White Chapel Murders. During Jack the Ripper. For that hundred days, the murder rate dropped 94 percent, to just five prostitutes. Their throats slashed. A kidney half eaten. Guts hung around the room on picture hooks. The sex organs and a fetus taken for a souvenir. Burglaries dropped by 85 percent. Assault by 70 percent.

Sister Vigilante, she says how nobody wanted to be the next victim of the Ripper. People locked their windows. More important, nobody wanted to be accused of being the killer. People didn't walk out at night.

During the Atlanta Child Murders, while thirty kids were strangled, tied to trees, and stabbed, beaten, and shot, most of the city lived in security and safety they'd never known.

During the Cleveland Torso Murders. The Boston Strangler. The Chicago Ripper. The Tulsa Bludgeoner. The Los Angeles Slasher . . .

During these waves of murder, all crime dropped in each city. Except for the showoffy handful of victims, their arms hacked away and their heads found elsewhere, except for these spectacular sacrifices, each city enjoyed the safest period in its history.

During the New Orleans Ax Man Murders, the killer wrote the local newspaper, the Times-Picayune. On the night of March 19, the killer promised to kill no one in a house where he could hear jazz music. That night, New Orleans was roaring with music, and no one was killed.

“In a city with a limited police budget,” Sister Vigilante says, “a high-profile serial killer is an effective means of behavior modification.”

With the shadow of this horrible bogeyman, with it stalking the streets downtown, nobody beefed about the unemployment rate. The water shortage. The traffic.

With the angel of death going door to door, people stayed together. They quit bitching and behaved.

At this point in Sister Vigilante's story, Director Denial walks by, calling and sobbing for Cora Reynolds.

It's one thing, the Sister says, a person getting killed, somebody with a crushed ribcage trying to catch another breath before they die, they heave and moan, their lips stretched wide, mouthing the air. Somebody with a crushed-in ribcage, she says, you can kneel next to them in the dark street with nobody around to watch. You can see their eyes glaze over. But killing an animal, well, that's different. Animals, she says, a dog, it makes us human. Proof of our humanity. Other people, they just make us redundant. A dog or cat, a bird or a lizard, it makes us God.

All day long, she says, our biggest enemy is other people. It's people packed around us in traffic. People ahead of us in line at the supermarket. It's the supermarket checkers who hate us for keeping them so busy. No, people didn't want this killer to be another human being. But they wanted people to die.

In ancient Rome, Sister Vigilante says, at the Colosseum, the “editor” was the man who organized the bloody games at the heart of keeping people peaceful and united. That's where the word “editor” really comes from. Today, our editor plans the menu of murder, rape, arson, and assault on the front page of the day's newspaper.

Of course, there was a hero. By accident, August 2, sunset at 8:34, a twenty-seven-year-old named Maria Alvarez was leaving a hotel where she worked as the night auditor. She stood on the curb, stopped to light a cigarette when a man pulled her back. That same instant, the monster rushed past. This man had saved her life. The city applauded on television, but in their hearts, they hated him.

A hero, this messiah, they didn't want. The idiot bastard who saved a life that wasn't their own. What people wanted was a sacrifice every few days, something to throw in the volcano. Our regular offering to random fate.

How it ended is, one night the monster got a dog. A hairy rag of a little dog on the end of a leash, tied to a parking meter on Porter Street, it stood and barked as the pounding came closer. The closer the sound came, the more the dog barked.

A store window webbed into a puzzle of broken glass. A fire hydrant clanked to one side, cracked cast iron, hissing a white curtain of water. The edge of a windowsill explodes in a spray of gravel and concrete dust. A smacked parking meter, jiggling in place, rattling the coins inside. A steel “No Parking” sign flaps down, torn from its metal post. The metal post still humming from some invisible impact.

One more stomp and the barking stopped.

The monster seemed to disappear after that night. A week went by, and the streets were still empty after dark. A month went by, and the editors found some new horror to put on the front page of the newspaper. A war somewhere else. Some new kind of cancer.

On September 10, sunset was at 8:02. Curtis Hammond was leaving a group-therapy session he attended every week at 257 West Mill Street. He was pulling down the knot of his tie when it happened. He'd just opened his collar button. It was when he'd just turned to look up the street. He smiled at the warm air on his face, shut his eyes, and breathed in through his nose. A month before, everyone in town knew him from the front page of the paper. From the television news. He'd pulled a night auditor away from getting killed by the monster. From getting smote by God.